Emergency Psychiatry: Characteristics of Patients Referred by Police to a Psychiatric Emergency Service

Police play an integral part in initiating mental health treatment and are a major source of referral to psychiatric emergency services (1,2,3,4,5). Violence is often a determinant of police involvement in the mental health care system. Emergency psychiatry outreach teams, composed of only mental health professionals, may not be safely equipped to respond to physical violence or serious threats of harm. Thus the initial contact with violent or potentially dangerous persons is often made by police, who have specific training and work within a structured system of communication in order to be responsive (6).

However, the role of law enforcement personnel in determining how mentally ill offenders are referred to the criminal justice system as opposed to medical settings is inadequately understood. A small number of studies have examined the characteristics of patients referred to psychiatric emergency services by police, including the type and severity of their mental illness, their level of dangerousness to themselves or others, their level of intoxication, and various demographic characteristics (1,2,3,4,5,6,7). However, the magnitude and direction of these differences has not been consistent across studies. For example, Steadman and colleagues (3) found that police referrals to a hospital in New York City were less likely than other referrals to involve psychotic individuals, more likely to involve persons with a "mild mental disorder," and less likely to result in admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit. In contrast, Way and colleagues (1) found that police referrals were more often due to dangerous behavior and that such patients had mental disabilities that were just as serious as those of other patients, required more time in the emergency setting, and were more often admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

We examined differences between patients referred by police to a large tertiary hospital in upstate New York and those referred to the hospital by other sources. We compared the reports of police officers in the field with subsequent evaluations of the same patients by clinicians in the psychiatric emergency service. We also compared patients who were referred by police with a group of patients who had been referred by other sources, matched by day of presentation to the psychiatric emergency service. Data evaluated included age, sex, town of residence, marital status, details of presenting symptoms, level of functional impairment, diagnosis, and family history as well as frequency of violence, suicidal behavior, substance abuse or intoxication, need for restraint, need for psychotropic medication, and admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit.

Methods

The setting for the study was the psychiatric emergency service of the University of Rochester Medical Center, a primary referral and evaluation facility for the greater Monroe County, New York, area. The facility serves an area with a population of approximately 850,000. Staffed by an interdisciplinary team of attending psychiatrists, psychiatric residents, master's-level social workers, registered and advanced-practice nurses, and medical, nursing, and social work students, this facility is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. More than 6,000 patients are seen each year.

The study sample comprised 100 consecutive police referrals to the comprehensive psychiatric emergency service between September 10 and October 20, 2000, and a control group consisting of 100 patients referred by other sources, matched day for day over the same period. The patients referred by police were under mental health arrest in keeping with the mental hygiene laws of New York State. Data on demographic characteristics, the condition of the patient on presentation to the psychiatric emergency service, and the evaluations of both police officers and mental health professionals were drawn from psychiatric emergency service records, mental health arrest documentation, and collateral reports documented in the patients' charts.

Results

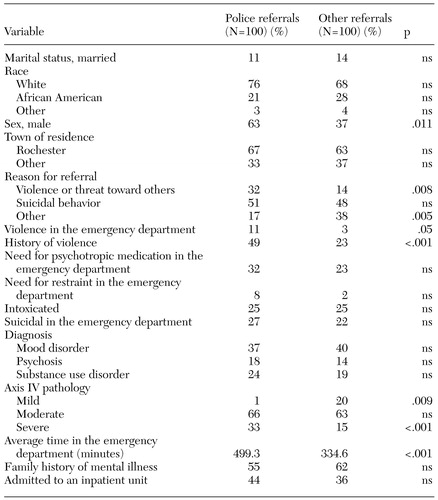

During the study period, 379 individual patients were seen in the psychiatric emergency service, including the 100 consecutive patients (26 percent) brought by police under mental health arrest. The other 279 (74 percent) were referred by other health care providers, the patients themselves, or other sources. Univariate comparisons between the police referrals and the matched comparison group of 100 of the referrals by all other sources are presented in Table 1. Compared with the patients who were referred by other sources, the patients referred by police were significantly more likely to be male (63 percent compared with 44 percent), to be referred because of violent behavior (32 percent compared with 14 percent), to exhibit violent behavior in the emergency department (11 percent compared with 3 percent), and to have a lifetime history of violence (49 percent compared with 23 percent). The patients who were referred by police were also rated as having more severe psychosocial stressors and spent more time in the emergency setting than did those referred by other sources. However, those referred by police were not significantly more likely to be admitted to inpatient psychiatric units (44 percent compared with 36 percent).

The two groups of patients were similar in their town of residence, ethnic group, age, marital status, frequency of intoxication, family history of mental illness, and rate of diagnosis of mood disorder, psychosis, and substance use disorder. More of the patients who were referred by police required psychotropic medication to control violence or potential violence in the emergency service (32 percent compared with 23 percent) and required restraint (8 percent compared with 2 percent), but these differences were not statistically significant.

For the purposes of this study, violence was defined as actual or threatened physical aggression toward another person or toward property. The overall proportion of police-referred patients who were considered to be violent by police officers in the field was 32 percent, compared with 11 percent who were considered to be violent by clinicians at the time of presentation to the psychiatric emergency service. The proportion of patients referred by other sources who were considered to be violent by police officers was 14 percent, compared with 3 percent whom psychiatric emergency service clinicians considered to be violent at the time of presentation to the psychiatric emergency service.

No significant difference was found between the two groups of patients in the proportion who were referred because they were considered to be suicidal (51 percent compared with 48 percent). Nor was there a significant difference between the two groups in the percentage who were determined to be suicidal in the psychiatric emergency service (27 percent compared with 22 percent). However, these percentages do show differences between police and emergency service clinicians in their assessments of suicidal behavior: among both police and nonpolice referrals, a larger proportion of patients were considered to be suicidal by police in the field than by clinicians in the psychiatric emergency service (51 percent compared with 27 percent in the police-referred group, and 48 percent compared with 22 percent in the non-police-referred group).

In addition, a psychiatric emergency service clinician's determination of a patient's being either actively or potentially violent was not associated with admission to an inpatient psychiatric unit. However, being categorized as suicidal was significantly associated with rate of hospital admission (data not shown).

Discussion and conclusions

Police initiated 26 percent of visits to this psychiatric emergency service during the study period. Patients who were referred by police had significantly more stressors and required more time for evaluation in the emergency service. However, although 40 percent of all patients were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, no statistically significant differences were noted in admission rates between patients referred by police and those referred by other sources. These findings differ from those reported for other psychiatric emergency services—one in New York and one in California (1,4). Our study did not use uniform or standardized measures of violence or suicidality and relied on determinations of individual police officers, patients, and clinicians, which may vary widely.

Patients who were referred to the emergency psychiatric service by police, although they did not have a higher rate of admission to the inpatient unit, were more likely than the patients in the control group (but not significantly so) to require psychotropic medication and physical restraint in the acute care setting. Behaviors requiring such measures were often determined by clinicians to be due to axis II, not axis I, pathology. Determining such causation in the field may be impossible for law enforcement personnel. Our findings do not necessarily reflect inappropriate assessment of patients by police officers in the field, but aspects of these determinations warrant further study. Continued investigation of characteristics of patients referred by police and of individuals who are brought to the criminal justice system rather than the psychiatric emergency service may help to explain the decision-making process used by police officers who are involved in removing individuals from the community as a means of ensuring safety. Some of these individuals have psychiatric histories and are later referred from jail to the psychiatric emergency service. A follow-up study of this population may further clarify how police officers make the distinction between mental hygiene arrest and further custody and access to the jail system.

The patients who were referred by police to our psychiatric emergency service were more violent than those referred by other sources but were no more suicidal or intoxicated and were no more likely to receive a diagnosis of an axis I disorder. Although patients referred by police were admitted to inpatient psychiatric units as often as those referred by other sources, a greater proportion of the police-referred patients required acute intervention in the psychiatric emergency service. As the number of these patients who require acute psychiatric services continues to increase, the structure, staffing, and resource allocation to these services may need to be reevaluated and adjusted so that the acute needs of this population can continue to be met.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the University of Rochester Medical Center, 300 Crittenden Boulevard, Rochester, New York 14642 (e-mail, [email protected]). Douglas H. Hughes, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients referred to a psychiatric emergency service by police and by other referral sources

1. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM: An analysis of police referrals to 10 psychiatric emergency rooms. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 21:380-397, 1993Google Scholar

2. Gillig P, Dumaine M, Stammer JW, et al: What do police officers really want from the mental health system? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:663-665, 1990Google Scholar

3. Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Borum W, et al: Comparing outcomes of major models of police responses to mental health emergencies. Psychiatric Services 51:645-649, 2000Link, Google Scholar

4. Watson M, Segal SP, Newhill CE: Police referral to psychiatric emergency services and its effect on disposition decisions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:1085-1090, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Sales GN: A comparison of referrals by police and other sources to a psychiatric emergency service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:950-952, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Lamb HR, Shaner R, Elliott DM, et al: Outcome for psychiatric emergency patients seen by an outreach police-mental health team. Psychiatric Services 46:1267-1271, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM: Factors predicting referral to inpatient or outpatient treatment from psychiatric emergency services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:703-708, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar