Comparing Outcomes of Major Models of Police Responses to Mental Health Emergencies

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study compared three models of police responses to incidents involving people thought to have mental illnesses to determine how often specialized professionals responded and how often they were able to resolve cases without arrest. METHODS: Three study sites representing distinct approaches to police handling of incidents involving persons with mental illness were examined—Birmingham, Alabama; and Knoxville and Memphis, Tennessee. At each site, records were examined for approximately 100 police dispatch calls for "emotionally disturbed persons" to examine the extent to which the specially trained professionals responded. To determine differences in case dispositions, records were also examined for 100 incidents at each site that involved a specialized response. RESULTS: Large differences were found across sites in the proportion of calls that resulted in a specialized response—28 percent for Birmingham, 40 percent for Knoxville, and 95 percent for Memphis. One reason for the differences was the availability in Memphis of a crisis drop-off center for persons with mental illness that had a no-refusal policy for police cases. All three programs had relatively low arrest rates when a specialized response was made, 13 percent for Birmingham, 5 percent for Knoxville, and 2 percent for Memphis. Birmingham's program was most likely to resolve an incident on the scene, whereas Knoxville's program predominantly referred individuals to mental health specialists. CONCLUSIONS: Our data strongly suggest that collaborations between the criminal justice system, the mental health system, and the advocacy community plus essential services reduce the inappropriate use of U.S. jails to house persons with acute symptoms of mental illness.

Police have always been key front-line responders in mental health emergencies. They have been labeled variously as "gatekeepers," street-corner psychiatrists, and social workers (1,2,3,4,5,6). Empirical analyses of these law enforcement- mental health system interactions have focused mainly on street-level interactions with persons who are possibly mentally ill (3,5) and on interactions with the staff of emergency rooms, where police often bring people for psychiatric evaluation (7,8,9). More recently, data on an innovative police-based diversion program (10) have been added to the literature. Although analyses of police-mental health system interactions have been very informative (11,12,13,14), they have not systematically examined a number of recently developed initiatives.

Criminal justice diversion programs typically are discussed in two general categories. In prebooking programs the diversion occurs before arrest charges are filed by police, and in postbooking programs it occurs after a person is booked into a jail with charges filed (15,16).

Police-based diversion programs fall in the prebooking category; arrests are avoided by having police officers make direct referrals to community programs. Police departments use innovative training and practices to avoid detaining people in need of emergency mental health services in local jails by arranging for community-based mental health and substance abuse services as alternatives. Another key element in many prebooking diversion programs is a designated mental health triage or drop-off center where police can transport all persons thought to be in need of emergency mental health services, usually under a no-refusal policy for police cases (17). No criminal charges are filed, and the triage center provides an appropriate treatment disposition.

The goal of the research reported here was to compare three different models of police responses to calls that police dispatchers categorize as calls for "emotionally disturbed persons."

Methods

The research approach was a comparative cross-site descriptive design of three different police response programs—programs in Birmingham, Alabama; and Memphis and Knoxville, Tennessee. At each site we examined a sample of about 100 police dispatch calls made between October 1996 and August 1997 in which the dispatcher radioed for police to respond to a situation that may have involved a mentally ill person. We determined how many calls resulted in a specialized response. We also looked at an additional 100 cases from each site in which a specialized response occurred to examine differences in case dispositions between programs. Although many other variables besides program type may have contributed to the differences observed, the results can still inform the field about how some programs being widely publicized are actually operating.

Each of the three study sites represents a distinct model for emergency responses to incidents involving persons appearing to have a mental health crisis. The sites were selected on the basis of a 1996 mail survey sent to all U.S. municipal police departments serving a population of 100,000 or more (N=174) (17). The survey sought to identify and describe specialized mental health responses by police to this type of incident. On the basis of survey results and a meeting with representatives of different programs, a typology of specialized responses that categorized the responses into three primary types was created (17). As described below, the Birmingham program represented a police-based specialized mental health response. The Memphis program represented a police-based specialized police response. The Knoxville program was a mental-health-based specialized mental health response. Each of the two police-based programs was rated as highly effective in our national survey.

Programs

Birmingham, Alabama.

For the past 20 years the city has funded a community service officer team within the Birmingham Police Department. Community service officers assist police officers in mental health emergencies by providing crisis intervention and some follow-up assistance. The officers are civilian police employees with professional training in social work or related fields. They dress in civilian clothes, drive unmarked cars, and carry police radios. They are not sworn police officers, do not carry weapons, and do not have the authority to arrest.

Newly hired community service officers participate in a six-week classroom and field training program. Since April 1993 six community service officers have worked with 921 police officers. The community service officers are based in each of the four major city police precincts and are available Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Twenty-four-hour coverage is provided by community service officers rotating on-call duty during weekends, holidays, and off-shift hours.

Besides responding to mental health emergencies, the officers attend to various social service types of calls, which involve domestic violence, needs for transportation or shelter, or other requests for general assistance. In 1997 the officers answered 2,189 calls. The most frequent request (N=731) was for assistance with mental-health-related situations.

Memphis, Tennessee.

The Memphis Police Department's crisis intervention team is a police-based program with specially trained officers and is considered the most visible prebooking diversion program in the U.S. (6,18). Other crisis intervention teams based on the Memphis model have been developed in Waterloo, Iowa; Portland, Oregon; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Seattle.

The stimulus for the program was a 1987 police shooting incident involving a mentally ill person. Under the aegis of the Memphis mayor's office, the police department formed a partnership with the Memphis chapter of the Alliance for the Mentally Ill, the University of Memphis, and the University of Tennessee to develop a specialized unit within the police department. Memorandums of agreement were signed indicating that services would be provided voluntarily and at no expense to the city of Memphis. The Memphis Police Department responded to this directive by developing the crisis intervention team. The officers on the team are trained to transport individuals they suspect of having mental illness to the University of Tennessee psychiatric emergency service after the situation has been assessed and diffused.

Currently, the crisis intervention team is composed of 130 patrol officers from its total force of 1,354 officers. The team officers provide a specialized response to "mental disturbance" calls in addition to their regularly assigned patrol duties. They cover four overlapping shifts in each precinct, providing 24-hour service.

After being selected for the crisis intervention program, police officers receive 40 hours of specialized training from mental health providers, family advocates, and mental health consumer groups, who provide information about mental illness and techniques for intervening in a crisis. The officers are issued crisis intervention team medallions that allow immediate identification of their role in the crisis situation. When the officer arrives on the scene, he or she is the designated officer in charge. During 1997 the specially trained officers responded to 6,940 mental disturbance calls, and in 3,261 cases they transported people to mental health services.

Knoxville, Tennessee.

The Knoxville mobile crisis unit serves a five-county area with a population of 475,000. Besides responding to calls in the community, the unit handles telephone calls and referrals from the jail, because the jail does not have an inpatient mental health program. The Knoxville Police Department has a force of 395 officers.

When this study began in 1996, the mobile crisis unit was composed of nine individuals who worked in two-person teams. During the time of the study, 24-hour coverage was provided by day, evening, night, and weekend team leaders. During the first quarter of 1996, the unit responded to a total of 1,943 situations, including 1,053 telephone calls and 890 field contacts. Jails made 16 percent of the referrals to the unit, 14 percent came from emergency rooms, 14 percent were self-referrals, and 13 percent were referred by police. Knoxville's mobile crisis unit was selected for this study because it and the Memphis program were under the same statewide managed care initiative.

Record reviews

Two types of records were used to gather information at each site—police dispatch calls and incident reports from the specialized response.

Police dispatch calls.

When a call is received by the police department, the dispatcher radios for the nearest available officer to respond. The dispatcher categorizes the call using standard codes reflecting the dispatcher's best assessment of the type of activity on the scene to which the police are being sent. To determine the frequency with which the specialized response team was called to the scene of the incident and to determine how often the incident ended in arrest, we examined approximately 100 consecutive "mental disturbance" dispatch files at each site.

Specialized response incident reports.

Our second type of record review involved 100 incident reports from mental health disturbance calls at each of the three sites, for a total of 300 cases in which a specialized response occurred. The objective was to compare the three specialized-response models in terms of avoiding arrest and incarceration. Incident data included information about individuals—demographic characteristics, behaviors, and symptoms—and the response time, intervention, and disposition provided.

Dispositions were classified into four mutually exclusive categories: arrest, in which criminal charges were filed; treatment, a broad category that included psychiatric hospitalization, detoxification, evaluation in a psychiatric emergency room, and admission to a general hospital for medical purposes; on-scene resolution, in which an incident was resolved on the scene or crisis intervention was provided at the scene; and referral, in which an individual was referred to a mental health specialist. We also collected information about whether the individual was transported by the specialized unit and where he or she was taken.

Data analysis

Analysis of the data from the three sites was conducted using SPSS, Windows version 9.0. The use of specialized responses and resulting arrests were cross-tabulated by site, and significant differences were identified by chi square analysis. One-way analysis of variance was used to corroborate the chi square test, and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to identify specific differences between the study sites.

Results

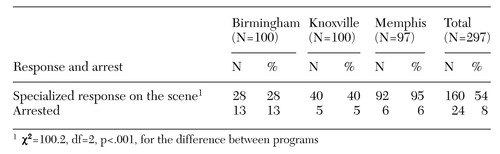

As shown in Table 1, statistically significant differences were found across the three sites in the proportion of mental disturbance calls eliciting a specialized response. The differences appear to be partly related to the program structure, especially the availability in Memphis of a crisis triage center with a no-refusal policy for police cases, and partly related to staffing patterns.

In Knoxville, where the mobile crisis unit was on the scene in 40 percent of the 100 cases examined, our data suggested that the unit's lengthy response times posed a significant barrier to use of the service by police. The mobile unit is responsible for covering five counties, including the city of Knoxville. Police often expressed frustration and concern about delays and frequently made disposition decisions to jail individuals, transport them to services, or drop them off "somewhere" without calling the unit.

In Birmingham, where 28 percent of the mental disturbance calls received a specialized response, there were only six community service officers for a police force of 921, severely restricting the availability of the officers with special training. The lack of availability was especially evident on weekends and nights when none of the community service officers were on duty, and only one was on call. In Memphis, which had only 130 crisis intervention team officers for a police force of 1,354, the specialized response was used in 95 percent of the 97 mental disturbance calls. The proportion of calls resulting in a specialized response was significantly higher in Memphis than in the other two cities.

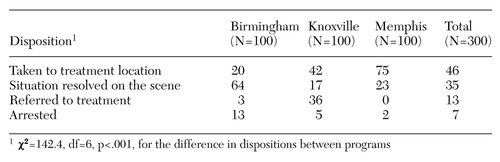

The next set of questions focused on the dispositions provided specifically by specialized response personnel. As Table 2 shows, for the total sample, 35 percent of the mental health incidents were resolved on the scene. Referrals to mental health specialists—case managers, mental health centers, or outpatient treatment—were made in 13 percent of all incidents. In 46 percent of cases, the individual was immediately transported to a treatment facility—a psychiatric emergency room, a general hospital emergency room, a detoxification unit, or another psychiatric facility—or admitted to the hospital. For the entire sample, only 7 percent of the incidents resulted in arrest.

As shown in Table 2, disposition and program type were significantly related. The Birmingham community service officers tended to resolve most incidents on the scene (64 percent of incidents). Knoxville's mobile crisis unit tended to refer individuals to mental health specialists as the predominant disposition (36 percent). The Memphis police-based crisis intervention team resolved incidents on the scene less often than did other programs (23 percent of incidents), yet the team was more likely than the other programs to transport individuals to services or to place them in some type of mental health treatment (75 percent).

Because all three programs were designed to divert persons suspected of having mental illness from jail to mental health services whenever possible, one way to measure their relative effectiveness as true jail diversion programs is to examine arrests resulting from calls specifically related to mental illness. Table 2 shows that all three programs had relatively low rates of arrest for these types of calls, with the rate in Memphis being particularly low at 2 percent.

Table 2 shows a 7 percent rate of arrest for all mental disturbance calls, which is much lower than the rate of 24 percent in Table 1. The difference reflects differences in the two types of records sampled. The incidents summarized in Table 2 were all handled by specially trained personnel. The calls that involved the Knoxville mobile crisis unit and the Birmingham community service officers also resulted in low arrest rates of 5 percent and 13 percent, respectively.

Discussion

Clearly, this study represents but a first step in assessing the effectiveness of police initiatives to address the needs of persons with mental illness, their family members, and the wider community. We have examined who shows up on the scene and how the police and mental health personnel address the immediate situation. We were not able to determine from our data what happens when individuals are referred to treatment or arrested or when the situation is resolved on the scene. Nonetheless, these data can provide insights both to frame debates about these interventions and to inform more rigorous evaluations of these and other innovative programs.

The Memphis crisis intervention team program had the most active procedures for linking people with mental illness to mental health treatment resources. Seventy-five percent of the mental disturbance calls in Memphis resulted in a treatment disposition, usually through transportation to the psychiatric emergency center. Certainly, not all of the people in these cases became engaged in effective, appropriate treatment, but a disposition that results in direct transport to a mental health treatment setting rather than to a jail is probably a positive option for most people.

The other innovative, police-based program, Birmingham's community service officers program, also had positive features. The specially trained officers appear to have been particularly active and adept at on-scene crisis intervention. They were able to resolve almost two-thirds of the mental disturbance calls on the scene without the necessity of further transportation or use of coercive procedures to facilitate treatment. On balance, their slim staffing pattern—six officers for a police force of 921 officers and four precinct areas, compared with the ratio in Memphis of 130 officers for a force of 1,354—and the limited response capability on nights and weekends may delay response and may limit the extent to which their services are used. They were on site for only 28 percent of all mental disturbance calls; in Memphis specially trained officers were on site for 95 percent of such calls.

In Knoxville the collaboration between the police and the mobile crisis unit allowed people with mental illness to be linked to treatment resources through transport or referral in about three-quarters of the cases, with very few incidents (5 percent) resulting in arrest. Just as the staffing ratio in the Knoxville program of nine officers for a police force of 395 falls between those of Memphis and Birmingham, so too does the arrest rate for mental disturbance calls. In fact, one of the key concerns expressed in this study about the Knoxville mobile crisis unit was that response times were excessive and impractical. The delayed response led officers not to use the unit's services as often as they otherwise might have and forced them to consider alternative dispositions. However, the mobile crisis unit was on the scene in 40 percent of the mental disturbance calls in our sample.

Whatever successes the three programs have can be linked to two key factors. The first is the existence of a psychiatric triage or drop-off center where police can transport individuals in crisis. Because this procedure reduces officers' down time, it is an attractive dispositional alternative, and it immediately places the person in crisis within the purview of the mental health system as opposed to the criminal justice system. In our earlier national survey of police departments, those who had access to such a facility were twice as likely to rate their response to mental disturbance calls as being effective as those who did not (6,13).

The second factor is the centrality of community partnerships. Each of the police departments views the program as part of its community policing initiatives. A core component of this policing philosophy is that police agencies should join with the community in solving problems (6,19). The Memphis crisis intervention team provides perhaps the clearest example of how this philosophy of police operations is applied to improve care for people with mental illness when they most need help. The crisis program is a collaboration between the criminal justice system, local mental health professionals—both treatment providers and academics—and the Memphis Alliance for the Mentally Ill.

Conclusions

Across all three sites, only 7 percent of mental disturbance calls resulted in arrest, a third of the rate reported by Sheridan and Teplin (3) for contacts between nonspecialized police officers and persons who were apparently mentally ill. In fact, our finding of a 2 percent arrest rate for the Memphis program is exactly the same as that reported by Lamb and colleagues (10) in their examination of the Los Angeles Systemwide Mental Assessment Response Team (SMART), which further reinforces the idea that a specialized response lowers the inappropriate use of arrest. Furthermore, in the study reported here, in more than half of encounters, mentally ill individuals were either transported to or referred directly to treatment resources. In another third, officers were able to intervene at the scene in a way that facilitated resolution of the crisis and allowed individuals to maintain their tenure in the community.

Our data strongly suggest that collaborations between the criminal justice system, the mental health system, and the advocacy community, when they are combined with essential elements in the organization of services such as a centralized crisis triage center specifically for police referrals, may reduce the inappropriate use of U.S. jails to house persons with acute symptoms of mental illness.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported under award 96-IJ-CX-008 from the National Institute of Justice of the U.S. Department of Justice. Supplemental funding was provided by the University of North Carolina-Duke program on mental health services research.

Dr. Steadman is affiliated with Policy Research Associates, Inc., 262 Delaware Avenue, Delmar, New York 12054 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Deane is with the State Police Academy of the New York State Police in Albany. Dr. Borum is with the Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute of the University of South Florida in Tampa. Dr. Morrissey is with the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Mental Health Services Research of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

|

Table 1. Proportion of mental disturbance calls resulting in specialized police responses and arrest at three sites

|

Table 2. Dispositions of cases handled by a specialized police response at three sites, in percentages

1. Cumming E, Cumming I, Edell L: Policeman as philosopher, guide, and friend. Social Problems 12:276-286, 1965Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Bittner E: Police discretion in emergency apprehension of mentally ill persons. Social Problems 14:278-292, 1967Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Sheridan EP, Teplin L: Police-referred psychiatric emergencies: advantages of community treatment. Journal of Community Psychology 9:140-147, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Teplin L: Keeping the Peace: The Parameters of Police Discretion in Relation to the Mentally Disordered. National Institute of Justice Final Report. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1986Google Scholar

5. Teplin L, Pruett N: Police as street-corner psychiatrist: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:139-156, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Borum R, Deane MW, Steadman H, et al: Police perspectives on responding to mentally ill people in crisis. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 16:393-405, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Steadman HJ, Morrissey JP, Braff J, et al: Psychiatric evaluations of police referrals in a general hospital emergency room. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 8:39-47, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Braff J, Morrissey JP: Profiling psychiatric cases evaluated in the general emergency hospital emergency room. Psychiatric Quarterly 59:10-22, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM: An analysis of police referrals to ten psychiatric emergency rooms. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 21:389-397, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lamb RH, Shaner R, Elliot DM, et al: Outcome for psychiatric emergency patients seen by an outreach police-mental health team. Psychiatric Services 46:1267-1271, 1995Link, Google Scholar

11. Ruiz P, Vazquez W, Vazquez K: The mobile crisis unit: a new approach in mental health. Community Mental Health Journal 9:18-24, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Meacham M, Acey KT: Considerations in evaluating a crisis outreach service. Crisis Intervention 5:25-35, 1974Google Scholar

13. Zealberg JJ, Christie SD, Puckett JA, et al: A mobile crisis program: collaboration between emergency psychiatric services and police. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:612-615, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Geller JL, Fisher WH, McDermeit M: A national survey of mobile crisis services and their evaluation. Psychiatric Services 46:893-897, 1995Link, Google Scholar

15. Steadman H, Barbera S, Dennis D: A national survey of jail diversion programs for mentally ill detainees. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1109-1113, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Steadman HJ, Morris SM, Dennis DL: The diversion of mentally ill persons from jails to community-based services: a profile of programs. American Journal of Public Health 85:1630-1635, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, et al: Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services 50:99-101, 1999Link, Google Scholar

18. Dupont R, Cochran S: Crisis Intervention Team Training Manual. Memphis, Memphis Police Department, 1996Google Scholar

19. Understanding Community Policing: A Framework for Action. Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1994Google Scholar