Community Integration of Elderly Mentally Ill Persons in Psychiatric Hospitals and Two Types of Residences

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Deinstitutionalization policy in the Netherlands has given rise to two new living arrangements for elderly long-term psychiatric patients. Both involve accommodation in mainstream residential homes for elderly persons, either concentrated in a specialized care unit or dispersed throughout the facility. The authors studied the effectiveness of these two housing models for the community integration of such residents compared with accommodation in a psychiatric hospital. METHODS: Three subsamples were selected: 49 residents in six units of concentrated housing, 47 residents in 12 units of dispersed housing, and 78 patients in 24 psychiatric hospital units, for a total sample of 174 participants. These samples were compared in a quasi-experimental, posttest-only design that used four measures of community integration: amount of perceived influence over one's daily life, involvement in social activities, social network size, and frequency of visits received from members of the network. To adjust for differences in the populations, the hospital patients were matched to the residential home residents, and confounding factors were controlled for. RESULTS: Residential homes afforded more privacy, were closer to public services, and had a more diversified population than psychiatric hospitals. Participants in dispersed housing experienced more personal influence over their lives than did hospital patients. Concentrated-housing participants were less enterprising and had smaller social networks. The three groups did not differ in the frequency of visits received from network members. CONCLUSIONS: Community-integrated facilities do not necessarily imply community-integrated residents. Only dispersed-housing residences were an improvement over hospitals, and then solely in terms of residents' influence over their own daily lives. The advantage of the dispersed-housing model is that it resembles independent living while its institutional nature offers structure and protection.

The deinstitutionalization of long-term psychiatric patients has led to the creation of a wide variety of community-based residential care facilities. In designing such facilities, a balance must be sought between providing structure and protection on the one hand and fulfilling the aims of normalization and community integration on the other. Nursing homes, a much-used alternative to psychiatric hospitals (1,2), put a one-sided emphasis on protecting the patients, and the balance has tipped so far in this direction that some observers speak of "transinstitutionalization" (3). A study by Shergill and colleagues (4) confirmed that older psychiatric patients in nursing homes have even less freedom than they did in mental hospitals.

Other types of residential care in the community have more successfully broken with the custodial care provided in psychiatric hospitals. Residents live in cleaner, more homelike surroundings (5), where they are subject to fewer rules and have more influence over their daily lives (5,6,7). But the scant research on their actual community participation suggests less positive outcomes. Their lives are characterized by social isolation, low participation in leisure activities, and stigmatizing experiences (8)

Supported independent living is the arrangement that most closely resembles full integration into the community. Although by definition this housing situation gives residents maximum influence over their lives, they too have been found to experience isolation—especially those with schizophrenia (9)—which has led Onaga and colleagues (10) to warn against underestimating the value of group living arrangements. In particular, the level of supportive transactions is low for residents who live independently (11). Borge and colleagues (12) have been the only researchers to find that residents in independent living arrangements undertake more activities away from home and are more socially active than institutionalized patients.

Although the new types of accommodation do appear to improve on psychiatric hospitals and nursing homes in restrictiveness, we still need to identify the optimum conditions for community involvement. The problem is how to enable mentally ill people to live in the community in conditions that are as normal as possible while shielding them from the consequences of their inability to take part in society and of society's inability to cope with them.

This study assessed the effectiveness of two new types of living arrangements now widely used in the resettlement of elderly psychiatric patients in the Netherlands (13). Both types have been created within residential homes for elderly persons. Such facilities are community based in the sense that they are located in ordinary neighborhoods, the residents live in fully self-contained apartments, there are also residents who are not mentally ill and need help only with activities of daily living, and the facilities represent normal accommodation for Dutch elderly persons. In our first model, "concentrated housing," psychiatric residents are housed in apartments in a separate unit in the facility; in the second model, "dispersed housing," psychiatric residents' apartments are located throughout the facility. The first model attaches more weight to the idea that psychiatric patients need structure; the second reflects a desire to have them live under normal housing conditions. In the first model, the residents spend a major part of their day in the dayroom, as in psychiatric hospitals; the second model puts more emphasis on the function of the apartment as an independent dwelling. Although in the second model the residents are expected to show more personal initiative, they still lead their lives within the "safe" context of the residential home. In both models, on-site mental health worker programs are operated by the local psychiatric hospital and staffed by hospital employees.

This study sought to determine the effectiveness of concentrated and dispersed housing in residential homes for elderly persons in comparison with psychiatric hospitals. Effectiveness was assessed in terms of the degree to which older people with chronic psychiatric conditions exercised influence over their own lives and took part in the community.

Methods

Design and sample

The three housing conditions were compared in a quasi-experimental design without pretest assessment. We decided on the posttest-only design because the admission rate of patients to the three housing conditions was too low to ensure a sample of sufficient size during the time of the study.

The source of the study samples was Dutch residential homes for elderly persons and psychiatric hospitals. Included were all 18 residential homes that had operated an on-site mental health worker program for at least one year at the time of the study, May 2000. Six homes provided concentrated housing, and 12 provided dispersed housing. Psychiatric hospitals already involved in an on-site mental health worker program were excluded from the sampling. Of the 18 hospitals that qualified, eight (24 units) agreed to take part in the study.

Inclusion criteria for the participants were being aged 65 years or older; duration of residence for at least six months, which was operationalized as the number of months that an individual participated in an on-site mental health worker program or the number of months that an individual had been hospitalized in his or her current psychiatric inpatient unit; having a DSM-IV diagnosis for at least two years; not having dementia; and having one or more limitations in daily functioning as a consequence of the mental disorder. Patients satisfying these criteria were asked to give their informed consent to be interviewed and to let us obtain information from their care providers. Patients who scored 4 or less on the Mini-Mental State Examination—12 (14) were disqualified from participation in the study. The consent procedure was approved by the medical ethical review committee of the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction.

Of the 78 concentrated-housing residents selected for the sample, 49 (63 percent) were willing and able to take part in the study, as were 47 (55 percent) of the 85 dispersed-housing residents. A slight nonresponse bias was detected in the concentrated-housing subsample; nonresponders indicated significantly more functional limitations.

In selecting the hospital patients, we took two additional steps in the sampling procedure. First, patients were required to satisfy a set of eligibility criteria for the on-site mental health worker program in the residential homes. The criteria were agreed to at a consensus meeting of all participating concentrated-housing and dispersed-housing homes. Second, hospital patients who met all criteria and gave informed consent were matched to the residential home participants in diagnosis, gender, and age. Ultimately, however, the composition of the hospital subsample made a disparity in mean age unavoidable.

Of the 172 hospital patients selected in this fashion, 78 (45 percent) ultimately completed the interview. Those who chose not to participate had significantly higher rates of psychotic disorders and functional limitations.

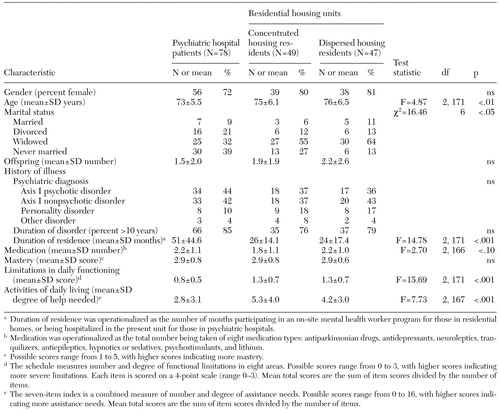

Gender of the participants is shown in Table 2 as the percentages of women in the three subsamples. Data on race were not collected.

Measures and procedures

We assessed the associations between the three housing conditions and the participants' community integration in terms of four variables. Amount of perceived influence over one's daily life was assessed with an adaptation of the Hospital Hostel Practice Profile (15) (Cronbach's alpha=.64). The adapted scale contained 20 dichotomous items on house rules, privacy, and autonomy rights as perceived by the residents.

Involvement in social activities was assessed with a nine-item scale specifically designed for the study (Cronbach's alpha=.72). Participants indicated whether, and if so where, they took a walk; did shopping; went to the post office; attended a performance, a social or games evening, or a church service; took part in a gym club or a hobby club; and visited someone. The higher the score, the greater the involvement in social activities.

Social network size was assessed with a social network instrument (16,17) that distinguishes eight domains, for each of which is recorded the number of persons with whom participants maintain regular and important contacts. The domains are partner, children and their partners, other family members, fellow residents, contacts through work and school, members of organizations, friends and acquaintances, and care workers. The participants named only the elder-care workers and mental health nurses who were important to them. The sum of all identified network members represents the size of the participant's social network.

For frequency of visits received, we recorded how often each network member visited the participant, with eight categories ranging from never to daily. The variable "visits received" is the product of the number of network members and the frequency of their visits.

Six types of data were collected to control for potential confounding. Demographic characteristics included gender, age, marital status, and number of offspring. Illness history included diagnosis, duration of disorder, and duration of residence; the last was operationalized as the number of months that an individual participated in an on-site mental health worker program or the number of months that an individual had been hospitalized in his or her current psychiatric inpatient unit. Medication was operationalized as the total number of medication types being taken. The eight types were antiparkinsonian drugs, antidepressants, neuroleptics, tranquilizers, antiepileptics, hypnotics or sedatives, psychostimulants, and lithium. Mastery was assessed with Pearlin and Schooler's Mastery Scale (18) (Cronbach's alpha=.71). Mastery refers to the degree to which individuals perceive that they are in control of their own lives; it can be understood as the opposite pole of a "hospitalized" life attitude.

Limitations in daily functioning were assessed with an observation schedule (19) that rates need for help in eight areas: self-care, household chores, use of public transportation, use of public services, daytime activities, financial management, making social contacts, and maintaining social contacts (Cronbach's alpha=.86).

Physical assistance needs were measured with a seven-item index of help required with activities of daily living, similar to the index proposed by Katz and colleagues (20) (Cronbach's alpha=.84).

The scales for the four outcome measures and for mastery were administered to each participant by a trained interviewer. Other data were obtained from care providers.

To verify whether the presumed differences between psychiatric hospitals and residential homes indeed existed, we also recorded certain data about each facility: percentage of residents in private rooms; floor space of private rooms; number of amenities in private rooms; average walking time to a bus stop, post office, and shop; and proportion of residents with a psychiatric diagnosis.

Data analysis

The independent variable "housing type" was recoded into two dummy variables, with the hospital patients used as the reference category. Associations between housing type and the dependent variables were determined by forced-entry multiple regression, which included both the dummy variables and all variables for which significant differences (p<.1) existed between the three subsamples. Analyses were carried out with SPSS version 8.0 (21).

Results

Characteristics of facilities

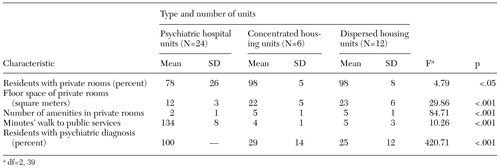

As shown in Table 1, the participating homes differed from the hospitals, as anticipated. They provided more privacy, with more residents living in private, self-contained apartments; and they afforded more opportunities for community involvement, because they were closer to public services and had more diversified populations of residents. Because the concentrated-housing and dispersed-housing conditions were comparable in these respects, institutional characteristics did not confound the comparison between concentrated and dispersed housing.

Characteristics of participants

Table 2 shows that the three samples of participants were comparable in psychiatric diagnosis and duration of disorder. Most participants had exhibited psychiatric symptoms for a long period; the disorders were about evenly divided between psychotic and nonpsychotic axis I disorders. Hospital patients were slightly younger and experienced fewer limitations in daily functioning and activities of daily living. The percentage of never-married individuals was highest among hospital patients and lowest among dispersed-housing residents. Duration of residence was inevitably shorter in the concentrated-housing and dispersed-housing conditions, given the more recent creation of the on-site mental health worker programs.

Community integration

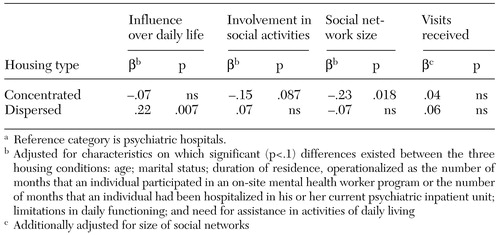

After adjustment for differences between the participant samples, the participants living in concentrated housing and psychiatric hospitals experienced about equally restrictive regimens. Residents thus had more influence over their daily lives in residential homes only if they lived in dispersed housing, as shown in Table 3. Comparison of crude item scores, using analysis of variance with Bonferroni adjustment, revealed several significant findings. Dispersed-housing residents were less likely to be required to ask permission to leave their unit (F=5.75, df=2, 170, p=.004), were less likely to be required to return home at a specified time (F=3.99, df=2, 169, p=.02), and had more choice of persons with whom to eat (F=4.75, df=2, 171, p=.01). Psychiatric hospital patients, in contrast, had more freedom in matters of self-care than participants in the two home groups (F=35.65, df=2, 171, p<.001).

Living in a residential home for elderly persons appeared to have no favorable effects on the residents' involvement in social activities, as shown in Table 3; and concentrated-housing residents were marginally less enterprising even than hospital patients. The concentrated-housing residents were less likely to go out for a walk (F=5.06, df=2, 171, p<.007), run an errand (F=8.65, df=2, 170, p<.001) or go to the post office (F=7.34, df=2, 171, p=.001).

Nor did living in a residential home yield a larger social network, as shown in Table 3. Concentrated-housing residents averaged 2.5 fewer network members than even hospital residents. The disparity was particularly evident in the domains of relatives other than offspring (F=4.86, df=2, 171, p=.009) and church and civic organizations (F=4.75, df=2, 171, p= .01). Comparison of crude domain scores further showed that dispersed-housing residents perceived significantly more fellow residents as important contacts than did concentrated-housing residents (F=3.35, df=2, 171, p=.038).

We also found no support for the hypothesis that residential homes for elderly persons were more accessible to visitors than were hospitals. Network members came to visit just as often in hospitals as in homes.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we investigated whether elderly people with long-term mental illness were more independent and better integrated into the community when accommodated in residential homes for elderly persons rather than in psychiatric hospitals. The residents we studied in residential homes were housed either in a specialized care unit, which we termed concentrated housing, or dispersed throughout the facility, which we termed dispersed housing. Only dispersed-housing residential homes were an improvement over hospitals, and then solely in terms of the participants' influence over their daily life. No significant associations emerged for other outcome measures. In fact, residents in concentrated housing proved less enterprising and had smaller social networks than did hospital patients.

The study had some limitations. The results emerged from a quasi-experimental design without pretest assessment. The advantage of having access to a large research sample was partially offset by our lack of control over the intake of participants into the conditions, which was a particular drawback for the comparability of the two residential-home types because those participants could not be matched.

Nevertheless, we had no cause to suspect that the unfavorable outcomes for concentrated housing were due to the residents' having more serious illness. The program administrators agreed on a common set of admission criteria for both residential housing models. Moreover, because in most regions only one model or the other was available, referring agencies were unlikely to choose between them on diagnostic grounds. Nor did our comparison of the two samples of residents reveal any substantial disparities.

Another limitation may have derived from our comparison group of hospital patients. Although the diagnoses and psychiatric histories of the hospital group were comparable to those of the residential home subsamples, the hospital patients were younger, more often unmarried, and resident longer in their current arrangement and had fewer limitations in daily functioning. Thus, as a group they were slightly more vital and less likely to experience relocation stress than were the residential-home groups. To adjust for these differences, we entered these characteristics into the analysis as potential confounders.

A further limitation was the high nonresponse rate—nearly 50 percent of the persons eligible for the study refused to participate. The rate was highest and most biased in the hospitals, where those who refused were more likely to have psychotic disorders or to be more seriously impaired. Treatment providers of the nonparticipants confirmed that paranoid ideas were a major motive for refusal. This finding means that the results have limited validity for participants with psychotic illnesses and those with more impairment.

Ours is yet another study that finds little support for the hypothesis that community-integrated services produce users that are integrated into the community. The residential homes we studied offered their residents more privacy than the psychiatric hospitals—a self-contained apartment—as well as more opportunities to take part in the community through the more central location and the proximity of age peers without mental illness. However, the success of these homes in facilitating their residents' taking advantage of these opportunities was very limited indeed. That finding was especially true for the concentrated housing residents, whose community involvement was less than that of the hospital patients and whose social networks were smaller. Explanations similar to those already found for nursing home accommodation may also apply here. This type of housing clings to the structured environment of the psychiatric unit, with its fixed rules and routines, while at the same time, in the name of deinstitutionalization, making concessions in terms of staff qualifications (3,22). Elder-care workers are more strongly focused on compensating for their patients' limitations than on mobilizing their potentials (23,24). Although residential homes may have an edge over mental hospitals in terms of location, the psychiatric sector generally has a head start when it comes to approaching psychiatric patients as "ordinary citizens."

The attractive feature of the dispersed-housing model is that it resembles independent living while its institutional nature provides a degree of structure and protection. That may be why the residents' relative freedom to come and go as they please did not lead to isolation and passivity. In a study of a comparable model, Perkins and colleagues (25) arrived at similar findings with respect to leisure activities and network contacts.

We were unable to confirm the merits of group living arrangements for the social life of psychiatric patients. That finding is consistent with participants' observations of day-to-day life in concentrated-housing units: the more the staff does for the residents, the less involvement the residents have with one another (23). The dispersed-housing residents listed the largest numbers of fellow residents in their social networks. However, that finding does not imply that dispersed-housing residents had to rely solely on their own initiative; seven of the 12 homes we studied provided the residents with special activity supervision.

Our general conclusion is that the physical integration of older psychiatric patients into mainstream residential homes for elderly persons does not foster the expected community involvement. However, because policy remains geared to discharging patients from psychiatric hospitals, it seems advisable to choose full integration into elder-care facilities rather than segregation within them.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZONMw).

Ms. Depla and Dr. de Graaf are senior research associates at the Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction, Post Office Box 725, 3500 AS Utrecht, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. van Busschbach is a senior research associate in the department of psychiatry at the University Hospital Groningen. Dr. Heeren is professor of old age psychiatry at the Utrecht University Medical Centre and medical director of the division of old age psychiatry at the Altrecht Institute for Mental Health Care in Utrecht.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychiatric hospital units compared with concentrated-housing and dispersed-housing units in residential homes for elderly long-term psychiatric patients

|

Table 2. Characteristics of participants living in psychiatric hospital units and in concentrated-housing and dispersed-housing units in residential homes for elderly long-term psychiatric patients

|

Table 3. Adjusted (standardized) regression coefficients of concentrated and dispersed housing in residential homes for elderly personsa on community integration of elderly long-term psychiatric patients

a Reference category is psychiatric hospitals.

b Adjusted for characteristics on which significant (p<.1) differences existed between the three housing conditions: age; marital status; duration of residence, operationalized as the number of momths that an individual participated in an on-site mental health worker program or the number of months that an individual had been hospitalized in his or her current psychiatric inpatient unit; limitations in daily functioning; and need for assistance in activities of daily living

c Additionally adjusted for size of social networks

1. Moak GS, Fisher WH: Geriatric patients and services in state hospitals: data from a national survey. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:273-276, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Gatz M, Smeyer MA: The mental health system and older adults in the 1990s. American Psychologist 47:741-751, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Goldman HH, Feder J, Scanlon W: Chronic mental patients in nursing homes: reexamining data from the national nursing home survey. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:269-272, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Shergill S, Stone B, Livingston G: Closure of an asylum: the Friern study of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 12:119-123, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shepherd G, Muijen M, Dean R, et al: Residential care in hospital and in the community: quality of care and quality of life. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:448-456, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Trieman N, Leff J, Glover G: Outcome of long stay psychiatric patients resettled in the community: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal 319:13-16, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Barry MM, Crosby C: Quality of life as an evaluative measure in assessing the impact of community care on people with long-term psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:210-216, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dewees M, Pulice RT, McCormick LL: Community integration of former state hospital patients: outcomes of a policy shift in Vermont. Psychiatric Services 47:1088-1092, 1996Link, Google Scholar

9. Bartels SJ, Mueser KT, Miles KM: A comparative study of elderly patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in nursing homes and the community. Schizophrenia Research 27:181-190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Onaga EE, McKinney KG, Pfaff J: Lodge programs serving family functions for people with psychiatric disabilities. Family Relations 49:207-216, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Nelson G, Hall GB, Squire D, et al: Social network transactions of psychiatric patients. Social Science and Medicine 34:433-445, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Borge L, Martinsen EW, Ruud T, et al: Quality of life, loneliness, and social contact among long-term psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services 50:81-84, 1999Link, Google Scholar

13. Depla MFIA, Pols AJ, Smits CHM, et al: Elderly psychiatric patients: the benefit of staying in a residential home with psychiatric support [in Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie 41:509-517, 1999Google Scholar

14. Kempen GIJM, Brilman EI, Ormel J: Normative data and a comparison of the MMSE-12 with the MMSE-20 in an elderly community sample [in Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie 26:163-172, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

15. Wykes T, Sturt E, Creer C: Practices of day and residential units in relation to the social behaviour of attenders. Psychological Medicine 12(suppl 2):15-27, 1982Google Scholar

16. Van Tilburg TG: Delineation of the network and differences in network size, in Living Arrangements and Social Networks of Older Adults. Edited by Knipscheer CPM, De Jong GJ, Van Tilburg TG, et al. Amsterdam, VU University Press, 1995Google Scholar

17. Van Tilburg TG: Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. Journals of Gerontology, B—Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 53(suppl):S313-S323, 1998Google Scholar

18. Pearlin LI, Schooler C: The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:2-21, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Wolf J: Care Innovation in Mental Health Care: Evaluation of Eighteen Innovation Projects [in Dutch]. Pub No 95-16. Utrecht, NcGv, 1995Google Scholar

20. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al: Studies of illness in the aged: the Index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 185:914-919, 1963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. SPSS for Windows: Standard Version 8.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc., 1997Google Scholar

22. Talbott JA: Nursing homes are not the answer (editorial). Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:115, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

23. Pols AJ, Depla MFIA, De Lange J: Caring for long-term mentally ill elderly in residential homes: opportunities and restrictions [in Dutch]. Pub No 98-2. Utrecht, Trimbos-institute, 1998Google Scholar

24. Pols AJ, Depla MFIA, De Lange J: "Do it yourself": care for autonomy of the elderly mentally ill in residential homes [in Dutch]. Maandblad Geestelijke Volksgezondheid 55:5-15, 2000Google Scholar

25. Perkins RE, Hollyman JA, Boardman CJ, et al: From long-stay patient to Sloane Ranger: outcome of resettlement of 15 old-long-stay psychiatric patients in "warden supervised" accommodation for the elderly. Journal of Mental Health 1:149-162, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar