Use of Antidepressants Among Canadian Workers Receiving Depression-Related Short-Term Disability Benefits

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: Little is known about how antidepressants are being used, but rising antidepressant expenditures and the accompanying impulse to control costs make this a critical issue to be addressed. The authors studied patterns of antidepressant use in a population of workers receiving depression-related short-term disability benefits to determine whether populations likely to benefit from antidepressants are using them and, if so, whether they are using them in a way that the benefits from their use are maximized. METHODS: The analyses were based on 1996-1998 administrative data from short-term disability and prescription drug benefit claims and occupational health department records for employees of three Canadian companies. RESULTS: Approximately 58 percent of employees who were receiving depression-related short-term disability benefits had made at least one antidepressant claim. Employees who did not use antidepressants typically reported significantly fewer symptoms at baseline on average than those who did. About 91 percent of the employees who used antidepressants filled at least one prescription for a guideline-recommended first-line agent. Approximately 79 percent of antidepressant dosages reflected those suggested by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment, and three timeframe indicators suggested that most patients used antidepressants within the recommended timeframes. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study represent an important first step in exploring the question of how antidepressants are used among workers with depression-related disability. For the most part, these workers and those whose depression was more severe were more likely to obtain antidepressants.

There is a growing awareness of the detrimental impact on national productivity as a result of depression among the working population (1,2,3). Estimates indicate that depression-related illnesses cost society upwards of $11.7 billion annually in absenteeism and another $12.1 billion in losses linked to reduced productivity (4). Because depression imposes such a drain on labor resources, there is an incentive to dampen its effects within the working population. Optimal use of antidepressants is one obvious approach to the problem (5,6,7). However, few studies have examined whether recommended treatments are being properly used.

Most studies to date have had two main foci. First, they have examined the trends in antidepressant use (8,9,10). From these studies we know that antidepressants have played a prominent role in the increase in prescription drug expenditures in the United States. In the year 2000, antidepressants became the top-selling prescription drug category in the United States, accounting for $10.4 billion in retail sales (8). Within this category, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most commonly used antidepressants—for example, citalopram, paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine.

The second field of inquiry has sought to identify cost-control mechanisms to mitigate the increase in antidepressant expenditures (11,12). Such an approach comes with an implicit assumption that these cost increases are related to either inappropriate or unnecessary use of antidepressants. However, because so few studies have explored how antidepressants are used, it may be premature to implement cost controls. If the increase in antidepressant expenditures is indicative of greater depression-related care, this increase may represent a desirable trend that should be encouraged (12). On the other hand, if antidepressant use patterns reflect an artificial need that has been manufactured by advertising (13) and prescription drugs are used indiscriminately, institution of measures to discourage the growing use of antidepressants may be justified. Thus the question of how antidepressants are used may be one of the most critical issues that needs to be addressed (14).

We begin to fill this gap in knowledge by describing patterns of antidepressant use in a Canadian population of workers receiving depression-related short-term disability benefits. These individuals are presumably a group for whom treatment could be highly effective and whom payers and policy makers should look upon with keen interest. We sought to address two main questions. First, are the populations who would likely benefit from antidepressants using them? Second, if these populations are using antidepressants, are they using them in a way that maximizes the benefits to be obtained from their use? To answer these questions, we compared actual use of antidepressants with benchmarks established by published clinical guidelines, positing interpretations for variations in patterns of use as well as implications for payers and employers.

Methods

Data sources and study population

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics board of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Research and the University of Toronto. Administrative data were taken from three major Canadian employers in the financial and insurance sector, with a combined workforce of approximately 63,000 employees nationwide, representing approximately 12 percent of the sector's workforce (15). All three companies had similar drug benefits. The primary information sources were company short-term disability claims, prescription drug claims, and occupational health department records. Because one company was relatively small, the claims taken from that company were those related to short-term disability episodes beginning between January 1996 and December 1998. For the remaining two companies, data were abstracted for claims initiated in 1997 or 1998.

A list of eligible disability claims from the companies' electronic databases formed the basis for identifying the occupational health records from which information was abstracted. Several procedures were instituted to protect employee confidentiality. Six trained nurse-abstractors were bound by a signed confidentiality agreement and worked in collaboration with designated staff in each company's occupational health department. A predefined set of data elements were extracted from each employee's company occupational health record for the disability episode of interest by using a customized, secure computerized data-entry form. Personal identifiers such as names, addresses, and identification numbers were not recorded during the abstraction process.

The employees who were included in our analysis met two criteria. First, they had depression-related absences from work for at least ten consecutive workdays before their disability-related leave commenced. This cutoff was based on the short-term disability criteria of the three companies that participated in the study. Second, employees had to have used their prescription drug benefits at least once during the study period for any type of prescription. Employees who did not meet this criterion were excluded because we could not ascertain whether their lack of antidepressant claims was due to their not filling a prescription for an antidepressant, not receiving a prescription for an antidepressant, or using another drug benefit plan.

Sociodemographic variables

Four categories of variables were created for the purpose of these analyses: sociodemographic variables, severity and complexity of the course of the episode, treatment plan variables, and recommended treatment variables. Sociodemographic variables included age and duration of tenure with the company. Both variables were calculated on the basis of the start date of the disability episode and the date of birth and date of hire, respectively.

Severity and complexity

We posited that antidepressant use might be influenced by both the severity and the complexity of the course of the episode. For example, we expected that more symptoms would be reported among employees who used antidepressants. Our severity indicator was based on a count of the numbers of depression-related disability symptoms reported on the short-term disability application form by the attending physician. Information was abstracted by using a checklist covering the major DSM-IV depressive symptom categories (16). A more detailed description of this indicator has been published previously (17).

We also assumed that complexity would be associated with different patterns of antidepressant use. This indicator attempts to capture patients' treatment resistance. Part of the reason for these more complex patterns of use lies in the fact that about 40 percent of patients do not respond to their first antidepressant (18) and often need to switch antidepressants. These patterns reflect a resistance to treatment (19) and thus might be associated with poorer compliance with guidelines.

On the basis of the literature (6,19,20), we created four mutually exclusive variables to capture the complexity of the antidepressant use: one fill only, indicating that the employee had only one prescription fill for antidepressants during the short-term disability episode; one antidepressant exclusively, indicating that the employee filled more than one prescription for an antidepressant and did not change antidepressants during the short-term disability episode; switched, indicating that more than one prescription was filled and that antidepressants were changed at least once during the short-term disability episode; and augmented, indicating that more than one prescription was filled and two prescriptions for different antidepressants were filled on the same day during the short-term disability episode.

Treatment plan indicator

Because antidepressant use is tied to physician prescribing, we created a variable to reflect the attending physician's perspective. This variable indicated whether antidepressants were part of the initial disability treatment plan submitted by the attending physician. We hypothesized that antidepressant use would be greater among employees for whom antidepressants were part of the original treatment plan proposed by the attending physician.

Recommended use indicators

In an effort to improve treatment of depression in the general population, at least three sets of depression-related clinical guidelines based on the scientific literature have been published since 1993 (21,22,23). The most recent guidelines were disseminated by the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment (CANMAT) in 1999. CANMAT is a national network of Canadian health care professionals from research, academic, and clinical centers who seek to improve the treatment of persons with mood and anxiety disorders. CANMAT's guidelines (23) are written for physicians practicing in general medical settings and were used to develop our antidepressant use indicators.

On the basis of patterns of drug use during the 200 days after initiation of the short-term disability episode, we developed four variables to characterize different aspects of drug use. The first of these—receipt of any antidepressant—was created as an indicator to identify whether the employee received any antidepressants at any time during his or her short-term disability episode. The second variable—use of recommended first-line antidepressant—indicates whether one of the CANMAT first-choice antidepressants—fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, bupropion, moclobemide, nefazedone, or venlafaxine—was used during the short-term disability episode. The third variable—use of recommended antidepressant dosage—indicates whether the calculated dosage (24) for the second-to-last antidepressant claim falls within recommended ranges. Following the method used by Simon and colleagues (24), we used the second-to-last claim to adjust for a stepwise increase in dosage over time.

In addition, three indicators were developed to characterize the initiation and duration of antidepressant therapy: antidepressant received within 30 days of the initiation of short-term disability, which captured whether the antidepressant prescription was filled within the 30-day period before or after the start of the short-term disability episode; antidepressant used for at least 30 days, which indicated whether the number of days' supply of antidepressant was greater than 30; and antidepressant used for at least four months, which indicated whether the number of days' supply of antidepressants was greater than 120—the typical time for the remission phase (23).

Days' supply indicates the number of days for which the physician prescribed the antidepressant and is recorded by the pharmacist from the physician's prescription. Using days' supply to create the dosage and duration indicators is predicated on the assumption that the employees used the prescriptions they filled as prescribed.

Analysis plan

Chi square tests were used to examine the strength of the association between guideline-recommended antidepressant use and dichotomous variables—for example, complexity and treatment plan indicators. Two-tailed t tests were used to test the associations between continuous variables—for example, number of symptoms—and guideline-recommended antidepressant use.

Results

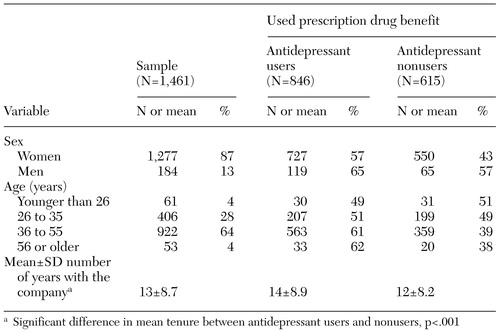

A total of 1,461 employees met the inclusion criteria. Demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. A majority of the employees included in the study were women (87 percent). The predominance of women in this sample reflects two phenomena. First, the finance and insurance sector, from which the sample was drawn, is composed primarily of women (67 percent) (15). Second, the prevalence of depression is higher among women than among men (25). Again reflecting the nature of this sector, the largest proportion of our sample was aged between 36 and 55 years (15). On average, the employees in our sample had been with their companies for about 13 years. A more detailed description of the study population can be found elsewhere (17).

Use of any antidepressant

Approximately 58 percent of employees who were receiving depression-related short-term disability benefits made at least one antidepressant claim. On average, those who used antidepressants had been with their companies for 14 years, compared with an average of 11 years for those who did not use antidepressants (t= 4.49, df=1,126, p<.001).

A significant difference was noted between the initial short-term disability treatment plan proposed by the attending physicians of employees who did versus those who did not use antidepressants. Approximately 28 percent of those who did not use antidepressants had an antidepressant prescribed in their initial treatment plans; by comparison, about 72 percent of those who used an antidepressant had an antidepressant recorded on their short-term disability application as part of their treatment plan (χ2=73.17, df=1, p<.001).

A significant difference was also found between the average numbers of short-term disability-related symptoms reported in the occupational health records of employees who did and those who did not use antidepressants. Employees who did not use antidepressants typically reported significantly fewer symptoms on average (mean of 3.4 symptoms) than those who did (mean of 4.1 symptoms) (t=5.11, df=1,459, p<.001).

Complexity of antidepressant use

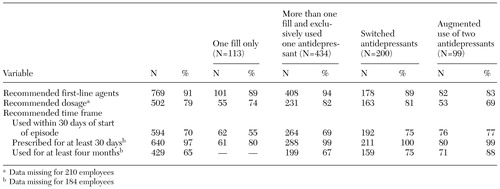

After the start of their short-term disability episode, more than 87 percent of the employees who used antidepressants filled more than one prescription for antidepressants. Specifically, about 51 percent of employees exclusively used one antidepressant throughout their episode. Approximately 36 percent either switched antidepressants or augmented their antidepressant use by using two antidepressants concurrently during their episode, as shown in Table 2.

When the number of symptoms reported for employees in each of these four mutually exclusive complexity categories was examined, the employees were clustered into two groups. No statistically significant difference was observed in the average number of reported symptoms for users with only one antidepressant fill and those who used one antidepressant exclusively (mean of 3.4 compared with 3.8 symptoms).

No significant difference was noted in the number of reported symptoms for employees who changed antidepressants and those who used more than one antidepressant simultaneously (mean of 4.7 compared with 5.0 symptoms). However, there were significant differences between these two groups. When data were combined, users in the first two use-pattern categories reported significantly fewer symptoms than those in the second two categories (mean of 3.8 compared with 4.8 symptoms; t=5.21, df=844, p<.001).

Guideline-recommended use

As shown in Table 2, overall, about 91 percent of the employees who used antidepressants filled at least one prescription for a guideline-recommended first-line antidepressant. Approximately 79 percent of antidepressant dosages reflected those suggested by CANMAT. Finally, the three timeframe indicators suggested that these employees also largely used antidepressants within the recommended timeframes. About 70 percent used antidepressants within the 30 days of the start of their episode, 97 percent used them for at least 30 days, and 65 percent used them for at least four months (Table 2).

However, differences were noted in guideline-recommended use by complexity of course. Compared with the other three groups of antidepressant users, those who had only one antidepressant fill were less likely to have had an antidepressant prescribed for at least 30 days (χ2=72.0, df=1, p<.001). At the same time, those with augmented use of two antidepressants were more likely to have used antidepressants for at least four months (χ2=21.13, df=1, p<.001).

Discussion

Our results point to several pieces of encouraging news for employers and payers. First, they indicate that workers who are disabled by depression are obtaining antidepressant treatment over the short term—that is, during the remission phase. Approximately 60 percent of the employees in our sample used antidepressants. By contrast, general population- based estimates such as those reported by Katz and colleagues (26) indicated that about 31 percent of the population with depression who obtained treatment used antidepressants. The results of our study suggest that unlike the general population of persons with depression, a majority of workers who are disabled by this condition obtain pharmaceutical treatment.

Second, we found that people get timely treatment with guideline-recommended first-line agents. A majority of antidepressant users in our study initiated use within 30 days of the start of their disability episode. In addition, a majority used second-generation antidepressants. This pattern is also consistent with the general trend toward the use of SSRIs (10,14).

These results have several important implications. Measures for controlling expenditures should be implemented with caution. Although the use of antidepressants is on the increase, there is a proportion of employees who need these medications and are successfully gaining access to them. Rather than impeding the use of antidepressants, a more long-term solution would be to develop a prescribing framework based on the assumption that a significant proportion of antidepressant users exhibit complex patterns of use. For example, Sclar and colleagues (27) developed an algorithm based on adverse-effect profile, dosage titration, and associated health service costs. With these criteria, they developed a ranking of the second-generation antidepressants from the most to the least preferable. Other studies have shown that this type of ranking could result in significant savings (19,28,29).

As with most studies that use administrative databases, our study had a number of limitations. First, we had to assume that the diagnoses on the claims forms were accurate (30,31,32). In addition, the data set did not report other treatments. Thus we did not account for other nonpharmaceutical treatments and did not consider depression outcomes. In addition, we followed the employees' use of antidepressants for only four months. Thus we cannot comment on ongoing use of antidepressants beyond the remission phase. Finally, our reliance on administrative data constrained our ability to comment on adherence (33). We assumed that employees who filled prescriptions took their medications. To the extent that this assumption is valid, our measures of use reflect a combination of partial adherence and physician prescribing patterns.

In terms of generalizability of our findings to U.S. settings, we would expect that U.S. workers in the financial and insurance sector would have access to the same type of health insurance coverage as the workers in the companies we studied. In fact, Canadian workers face the same types of barriers to prescription drugs as those faced by U.S. workers in that the public plan does not include drug benefits. Furthermore, physicians practicing in Canada are exposed to the same types of clinical guideline recommendations, and Canadians have access to the same antidepressants as their U.S. counterparts. Thus the results observed in our study population are likely to be generalizable to employees in the same sector in the United States.

Our results represent an important first step in describing the quality of antidepressant use among workers who are most affected by depression. Our findings raise a number of questions. Would similar results be observed in all business sectors? Do the same patterns of use apply among employees who use antidepressants but who do not claim disability benefits? Finally, what other nonpharmaceutical treatments were used by the employees who claimed disability benefits?

Conclusions

Our results indicate that, for the most part, workers who are disabled by depression are gaining access to antidepressants. Indeed, the findings suggest that a higher proportion of workers who are disabled by depression obtain pharmaceuticals than would have been expected on the basis of estimates from population-based studies. Furthermore, those who use antidepressants are using them in concordance with guideline recommendations.

Our findings also suggest that it may be counterproductive for employers and managers to use blunt instruments to reduce prescription drug expenditures. It is shortsighted to institute blanket policies that could decrease access to medications and inhibit their use. Instead, a more long-term solution with a potentially greater impact would involve a two-pronged approach, including early recognition of depression and a focus on developing formularies and algorithms to assist in the most efficient use of medications.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Ontario Roundtable on Appropriate Prescribing. Dr. Dewa and Dr. Hoch gratefully acknowledge the support provided by their Career Scientist Awards from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Dr. Hoch also acknowledges financial support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Dr. Dewa, Dr. Goering, and Dr. Lin are affiliated with the health systems research and consulting unit of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto and with the department of psychiatry of the University of Toronto, 33 Russell Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2S1 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Hoch is with the department of epidemiology and biostatistics of the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario. Mr. Paterson is affiliated with the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto, with which Dr. Lin is also affiliated.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of employees who participated in a study of antidepressant use among workers receiving depression-related disability benefits

|

Table 2. Use of antidepressants among 846 employees receiving depression-related short-term disability benefits

1. Kessler RC, Barber C, Birnbaum HG, et al: Depression in the workplace: effects on short-term disability. Health Affairs 18(5):163-171, 1999Google Scholar

2. Berndt E, Bailit HL, Keller MB, et al: Health care use and at-work productivity among employees with mental disorders. Health Affairs 19(4):244-256, 2000Google Scholar

3. Birnbaum HG, Greenberg PE, Barton M, et al: Workplace burden of depression: a case study in social functioning using employer claims data. Drug Benefit Trends 11(8):6BH-12BH, 1999Google Scholar

4. Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, et al: The economic burden of depression in 1990. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:405-418, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

5. Berndt ER, Finkelstein SN, Greenberg PE, et al: Workplace performance effects from chronic depression and its treatment. Journal of Health Economics 17:511-535, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Claxton AJ, Chawla AJ, Kennedy S: Absenteeism among employees treated for depression. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 41:605-611, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mintz J, Mintz LI, Arruda MJ, et al: Treatments of depression and the functional capacity to work. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:761-768, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Prescription Drug Expenditures in 2000: The Upward Trend Continues. Washington, DC, National Institutes for Health Care Management, 2000Google Scholar

9. Foote SM, Etheredge L: Increasing use of new prescription drugs: a case study. Health Affairs 19(4):165-170, 2000Google Scholar

10. Dewa CS, Goering P: Lessons learned from trends in psychotropic drug expenditures in a Canadian province. Psychiatric Services 52:1245-1247, 2001Link, Google Scholar

11. Kleinke JD: Just what the HMO ordered: the paradox of increasing drug costs. Health Affairs 19(2):78-91, 2000Google Scholar

12. Chernew M, Cowen ME, Kirking DM, et al: Pharmaceutical cost growth under capitation: a case study. Health Affairs 19(6):266-276, 2000Google Scholar

13. Barents Group LLC: Factors Affecting the Growth of Prescription Drug Expenditures. Washington, DC, National Institutes for Health Care Management, 1999Google Scholar

14. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203-209, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Statistics Canada: Labour Force 15 Years and Over by Broad Occupational Categories and Major Groups (Based on the 1991 Standard Occupational Classification) and Sex, for Canada, Provinces and Territories, 1991 and 1996 Censuses (20% Sample Data). Catalogue 93F0027XDB96007 in the Nation Series, Ottawa, 1996Google Scholar

16. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

17. Dewa CS, Goering P, Lin E, et al: Depression-related short-term disability in an employed population. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 44:628-633, 2002Google Scholar

18. Spigset O, MÅrtensson B: Drug treatment of depression. British Medical Journal 318:1188-1191, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Thompson D, Buesching D, Gregor KJ, et al: Patterns of antidepressant use and their relation to costs of care. American Journal of Managed Care 2:1239-1246, 1996Google Scholar

20. Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, et al: The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1128-1132, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder in Adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 150(4 supple):iii-26, 1993Google Scholar

22. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2: Treatment of Major Depression. Pub 93-0551. Washington, DC, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

23. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatment: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Pharmacological Treatment of Depression. Toronto, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

24. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Wagner EH, et al: Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:399-408, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Offord DR, Boyle MH, Campbell D, et al: One-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder in Ontarians 15 to 64 years of age. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 41:559-563, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Lin E, et al: Medication Management of Depression in the United States and Ontario. Journal of General Internal Medicine 13:77-85, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Robinson LM, et al: Economic appraisal of antidepressant pharmacotherapy: critical review of the literature and future directions. Depression and Anxiety 8(suppl 1):121-127, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

28. Tierney R, Melfi CA, Signa W, et al: Antidepressant use and use patterns in naturalistic settings. Drug Benefit Trends 12:7-12,2000Google Scholar

29. Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Goering P: Using forecasting models to estimate the effects of changes in the composition of claims for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on expenditures. Clinical Therapeutics 23:292-306, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Melfi CA, Croghan TW: Use of claims data for research on treatment and outcomes of depression care. Medical Care 37:AS77-AS80, 1999Google Scholar

31. Browne RA, Melfi CA, Croghan TW, et al: Issues to consider when conducting research using physician-reported antidepressant claims. Drug Benefit Trends 10:33;37-42, 1998Google Scholar

32. Motheral BR, Fairman KA: The use of claims databases for outcomes research: rationale, challenges, and strategies. Clinical Therapeutics 19:346-366, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Edgell ET, Summers KH, Hylan TR, et al: A framework for drug utilization evaluation in depression insights from outcomes research. Medical Care 37:AS67-AS76, 1999Google Scholar