Rehab Rounds: Involving Families in Rehabilitation Through Behavioral Family Management

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: A wide variety of family psychoeducational approaches for persons with serious and persistent mental illness have been developed and used by mental health professionals since the introduction of such approaches in the 1960s (1). From 1970 to 1975, multifamily psychoeducation was implemented for large numbers of clients and relatives at the Oxnard Mental Health Center (2) and was followed by systematic studies of multifamily therapy at the Maudsley Hospital in London in 1976 (3) and Camarillo State Hospital in California in 1978 to 1980 (4). The type of intervention that arose from this work comprised a series of educational sessions followed by training in communication and problem-solving skills. Behavioral learning principles were used to promote acquisition of knowledge, coping skills, and problem solving for families. Other procedures and variants on this theme have proliferated throughout the United States and in many other countries (5). Most of these approaches have in common an adherence to practical goals that are individualized for each family and an educational rather than a "therapeutic" slant.In an attempt to overcome the obstacles to widespread clinical use of family interventions, a variety of dissemination strategies have been tried, including academic detailing, consensus building among all stakeholders (6), and the development of modules consisting of trainers' manuals, consumers' workbooks, slide shows, and video-assisted learning (7,8). This month's column describes one of the variants of family psychoeducation—behavioral family management—and its components, illuminated by case vignettes and results of efficacy studies.

Because behavioral and educational techniques are used to help families cope with and manage the stress and challenges of interacting with a mentally ill relative, the term "behavioral family management" was coined. The term "therapy" was avoided in the interest of protecting families from the stigma associated with "treatment" and the implicit blame associated with the illness of a relative. Although the labeling of any form of intervention may have some unintended and undesirable effects, it is more important to identify the actual components of the services being provided, the proximal aims of each component, and the longer-term benefits that accrue when the mediating aims are attained.

Behavioral family management can be considered rehabilitative because it equips all members of the family, including the individual who has a mental disorder, with know-how, skills, and supports to function better in daily life and to reach their own personal goals. In this column we describe the stepwise elements of behavioral family management, illustrating each step with a clinical vignette.

Scope and impact of behavioral approaches to family intervention

We first take a brief detour to provide a broader perspective of behavioral approaches to families that have a mentally ill member as well as the efficacy and effectiveness of these approaches. The distinguishing feature of behavioral family interventions is the application of principles of operant and social learning. These principles have enabled scientist-practitioners to design family interventions for a broad spectrum of clinical problems. Because behaviorally oriented clinicians integrate measurement of process and outcome in their techniques, ample empirical validation has been demonstrated for behavioral family interventions. Some of the mental disorders that have been effectively addressed by behavioral family interventions are schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression, eating disorders, substance use disorders, somatoform disorders, sexual dysfunction, anxiety disorders, autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders, mental retardation, learning disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders, and elimination disorders of childhood. References documenting the efficacy and effectiveness of these interventions can be obtained from the corresponding author.

In the treatment of schizophrenia, behavioral family management and variants of this approach that have similar learning-based, educational, and structured methods were shown to have clinical, social, family, and economic benefits in 22 controlled studies conducted in nine countries with services extending for at least six months (9). Because schizophrenia requires comprehensive and coordinated treatments, the family intervention was used in conjunction with pharmacotherapy and case management. Beneficial outcomes have been documented for reductions in relapse and hospitalization, improvements in social and community functioning, reductions in family burden, improvements in quality of life, and enhancement of cost-effectiveness.

Steps used in behavioral family management

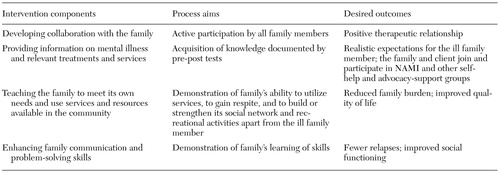

Four key components of behavioral family management are depicted in Table 1, along with the proximal aims of the component and the desired longer-term outcomes. The first step is to engage the family in a collaborative and mutually respectful working relationship. From the very start, it is important to involve all members of the family—including the affected client—in the treatment and rehabilitation team. Because having an informed and supportive family often makes the difference between success and failure in the rehabilitation enterprise, family members and all treatment providers—often from different agencies—must be kept apprised of progress, problems, and treatment plans. Clients almost always agree to this shared approach involving a broad diffusion of information to key family members. However, when clients want certain events to be kept confidential, their desires are respected.

For example, Mr. J, aged 24 years, had been living with his parents and suffering from untreated schizophrenia for five years. His parents were unable to persuade him to seek professional assistance. They finally consulted a psychiatrist on their own, and the psychiatrist agreed to make several home visits to get acquainted with Mr. J in his familiar environment, where he felt safe. The client's personal goals of being able to work, having friends, and regaining his driving privileges were consensually validated by his parents and served as the motivational lever for starting treatment.

The second phase of the intervention is to effectively teach the entire family about the nature of the mental illness and the available services and community resources. For example, Ms. M, her parents, and her brother participated in the medication management module and symptom management module of UCLA's social and independent living skills program (10), developing a relapse-prevention plan that acquainted all of them with the early warning signs of relapse and an action plan for intervention when warning signs emerged. Ms. M learned how to negotiate medication issues with her psychiatrist and how to self-administer her medication reliably. Her parents gained social support and coping skills from attending meetings of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) and participating in NAMI's Family-to-Family education program.

Because the relatives of a person with a persisting and disabling mental disorder can easily succumb to the emotional and financial burdens of caregiving, the next step in the intervention aims to encourage and assist family members to reconstruct a life of their own. This may include maintaining participation in NAMI self-help and support groups as well as taking vacations and resuming visits and social contacts with friends and relatives, all the while being able to speak plainly and candidly about the mental disorder they are coping with. One elderly couple who had been overwhelmed as a result of caring for their adult son, who had schizophrenia, took cruise vacations and joined a book club at their local library. These activities benefited not only the couple but also their son, whose stress levels subsided because his parents were no longer emotionally overinvolved with him.

The final step in behavioral family management is directive and structured teaching of communication and problem-solving skills using video or live modeling, role-playing, coaching, positive feedback, and homework assignments. For example, Mr. G and his parents were in turmoil because of Mr. G's feelings of being overstimulated by lack of privacy in the family's small, cramped home. Until Mr. G could save enough money to get his own apartment, he and his family were taught to use communication skills, such as making positive requests and using active listening. They use their improved communication to find ways of increasing his privacy at home. In the problem-solving process, Mr. G and his parents decided to redecorate a little-used room in their attic so that he could have his own room.

Recycling know-how and skills for the long haul

Because caring for persons with serious and persistent mental disorders requires consistency, continuity, and coordination of efforts, the four components of behavioral family management are repeatedly recycled and practiced for years, albeit with varying frequency. Just as maintenance antipsychotic medication needs to be used indefinitely, so do rehabilitation modalities such as family interventions. Recovery from schizophrenia and related disorders does not occur in a straight line. And even if recovery is attained, it is not guaranteed for the years ahead. The course of illness is affected by too many factors, many of which are outside the control of the family, the client, and professional treaters. Thus it is the responsibility of professionals to revisit the four components of this model as frequently as needed. The journey to optimal rehabilitation for the client and members of his or her family is more important than the destination. Using behavioral family management in a consistent manner can yield dividends, including fewer relapses and hospitalizations, better social and emotional functioning, less stressful family relations, and a better quality of life.

Afterword by the column editors: Clinical and educational programs for families of persons with serious and persistent mental disorders have been previously featured in the Rehab Rounds column. The variants of family intervention can be categorized by the four components presented in this month's column. For example, the programs developed by Amenson and Liberman (7) and by Sherman (11) focus on the second and third components. The multifamily group therapy developed and validated by McFarlane and colleagues (12) covers all four components. As more components are added to any family intervention, a wider range of favorable outcomes can be expected. However, unless the components of the program can be demonstrated to exert their specific and proximal impact, there is little reason to expect the intervention to achieve its desired outcome. This was, in fact, the case in the multisite Treatment Strategies of Schizophrenia project sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health. The families participating in the more intensive behavioral family management condition did not improve their communication or problem-solving skills and hence achieved outcomes no better than those of the families who were assigned to the less intensive educational and support program (13).

Ms. Liberman is a medical student at Brown University Medical School in Providence, Rhode Island. Dr. Liberman, who, along with Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., is editor of this column, is professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)/David Geffen School of Medicine and director of the UCLA psychiatric rehabilitation program. Send correspondence to Dr. Liberman at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, California 90024 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Relationship between behavioral family management and clinical outcomes

1. Liberman RP: Behavioral approach to family and couple therapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 40:106-118, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Liberman RP, DeRisi WJ, King LW: Behavioral interventions with families, in Current Psychiatric Therapies. Edited by Masserman J. New York, Grune and Stratton, 1973Google Scholar

3. Falloon IRH, Liberman RP, Lillie F, et al: Family therapy with schizophrenics at high risk of relapse. Family Process 20:211-221, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Falloon IRH, et al: Interpersonal problem-solving for schizophrenics and their families. Comprehensive Psychiatry 22:627-630, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Dixon L, Adams C, Lucksted A: Update on family psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:5-20, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dixon L, McFarlane W, Hornby H, et al: Dissemination of family psychoeducation: the importance of consensus building. Schizophrenia Research 36:339, 1999Google Scholar

7. Amenson CS, Liberman RP: Dissemination of educational classes for families of adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 52:589-592, 2001Link, Google Scholar

8. Glynn SM, Liberman RP, Backer TE: Involving families in services for the seriously mentally ill: a video-assisted module with trainer's manual and participants' workbooks. Camarillo, Calif, Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants, 2003. Available at www.psychrehab.comGoogle Scholar

9. Falloon IRH, Held T, Coverdale J, et al: Family interventions for schizophrenia: a review of long-term benefits of international studies. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 3:268-290, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA social and independent living skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43-60, 1994Google Scholar

11. Sherman MD: The Support and Family Education (SAFE) program: mental health facts for families. Psychiatric Services 54:35-37, 2003Link, Google Scholar

12. McFarlane WR, Lukens EP, Link B, et al: Multiple family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679-687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Liberman RP, Mintz J: Reviving applied family intervention. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1047-1048, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar