Practical Psychotherapy: Adaptation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy by a VA Medical Center

In the wake of the assault of 83 women and seven men at the Navy Pilot's Tailhook Association Convention in September 1991, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) received a mandate in 1992 to provide counseling for female veterans who were victims of sexual assault or harassment while in the military (1). For a subset of sexually traumatized female veterans, counseling for the trauma is complicated by more severe psychopathology (2). For these women, the sexual trauma in the military often represents a retraumatization (3). Their clinical picture frequently resembles that of patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (4)—more chronic, characterologic, and impaired with multiple comorbidities—and requires more intensive treatment than needed by women with less severe pathology (4,5,6).

Despite considerable investment of VA resources in combat-related PTSD treatment, there remains a large group of male veterans with PTSD who are chronically ill and who are considered treatment resistant (5,7,8). This chronicity is likely due to several factors, but the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders is certainly contributory (8,9). For example, although 85 percent of the men treated in specialized VA PTSD treatment programs receive a diagnosis of PTSD or subthreshold PTSD, it is also relatively common for these individuals to have personality and substance use disorders (9). As with female veterans, male veterans with chronic PTSD are more likely than those without PTSD to have been retraumatized by their military experiences (10). This retraumatization may be another factor in the relative lack of efficacy of first-line PTSD treatments that are used more successfully in nonveteran populations—for example, exposure therapy (5).

We sought a treatment approach that could address the characterologic issues noted above as well as PTSD and other psychiatric symptoms. Dialectical behavior therapy is a cognitive-behavioral treatment that integrates validation and dialectical strategies into the therapeutic interaction. It was specifically designed to treat borderline personality disorder (11).

We believed that dialectical behavior therapy would be a good clinical approach for some veterans with chronic trauma-related disorders, because these individuals were noted to have features similar to those noted among patients with borderline personality disorder: high rates of hospitalization and substance abuse, impulsivity, mood instability, and interpersonal difficulties (2,12,13). We describe the development of a dialectical behavior therapy program in a large Midwestern VA medical center.

Standard dialectical behavior therapy consists of four essential treatment components: individual therapy, skills training, telephone coaching, and a consultation group for clinicians. The individual therapy, skills group, and consultation group are conducted weekly. Individual dialectical behavior therapy requires a validating therapeutic relationship and uses cognitive-behavioral techniques to facilitate behavior change and skills acquisition. Individual therapists are available to "coach" patients through crises by telephone.

The skills are taught in modules and include mindfulness, interpersonal skills, regulation of emotions, and distress tolerance. The consultation group provides a venue in which clinicians can receive consultations about their patients, coordinate care, and get feedback from other clinicians.

Clinicians

Clinicians interested in learning dialectical behavior therapy attended a two-day workshop and participated in a six-month multidisciplinary self-study group. From December 1996 through November 2000, a total of 33 clinicians provided services. The clinicians varied in their clinical orientation before learning dialectical behavior therapy—about two-thirds identified themselves as cognitive-behavioral therapists and 30 percent as psychodynamic therapists. To further facilitate program development, we paid for additional consultation from clinicians who had studied with Linehan (11) to become dialectical behavior therapy trainers. Although more intensive training in dialectical behavior therapy is recommended, this training process allowed for sufficient skills acquisition (14).

Program participants

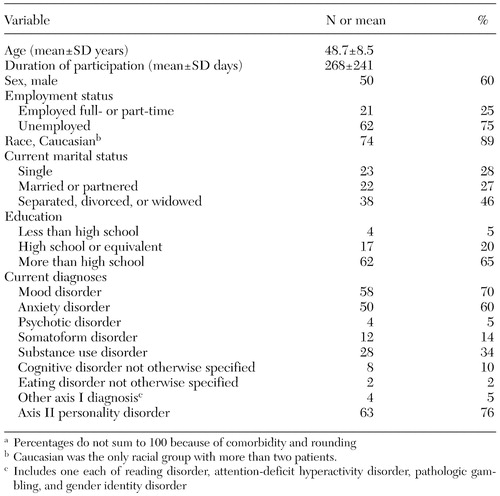

Thirty-three female and 50 male patients participated in the dialectical behavior therapy programs from December 1996 through November 2000. During the year before enrolling, 26 patients had one or more psychiatric hospitalizations, for a total of 47 admissions. All patients had undergone treatment and received ancillary treatment while participating in dialectical behavior therapy (medication, case management, or both). Characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Most patients were in the program for one continuous trial, but nine enrolled in the program more than once—that is, with at least six months between trials. A majority (66, or 78 percent) were in the program for at least three months, and about half (42 patients) were in the program for more than six months. No differences were noted between men and women in the duration of participation.

Consistent with the origins of the program, most patients—70 percent of women (N=23) and 62 percent of men (N=31)—had a history of trauma meeting DSM-IV criterion A1 for PTSD documented. Half the patients (N=42) met criteria for PTSD at the time of the study. A majority (73 patients, or 88 percent) had more than one axis I diagnosis for which they were seeking treatment. A little more than half (34 patients, or 55 percent) of those with a personality disorder met criteria for borderline personality disorder.

Clinicians considered, in retrospect, that most program participants were appropriate for dialectical behavior therapy. Dialectical behavior therapy was considered inappropriate for only four of the 83 patients: one who was paranoid and was dishonest about his drug dependence; one who had a diagnosis of schizoid personality disorder and had difficulty seeing the need for this therapy; one whose primary clinical issue was gender identity disorder, for which dialectical behavior therapy is not considered to be particularly helpful; and one who was functionally illiterate.

Program modifications

We retained the essential features of the dialectical behavior therapy treatment model but made four modifications. In Linehan's model (11), therapists are generally available for coaching calls according to the patient's need, because patients can better generalize skills if they are helped to apply them when they are most needed. Although all therapists were available for coaching calls, most were available only during normal clinic hours. It is possible that this limitation diminished the effectiveness of the therapy; however, this stipulation attracted to the program clinicians who would not otherwise have participated.

The second modification evolved because some patients had cognitive or learning impairments and required additional help understanding the skills and completing the written homework assignments. Skills tutors were provided for these patients. Tutors were clinicians or clinician trainees who met with patients once a week for one hour. Tutors attended the weekly consultation group meetings. The concept of tutors fits well within the dialectical behavior model.

Our third modification was the development of a step-down group for patients who completed the initial dialectical behavior therapy treatment and acquired most of the skills but who still felt a need for ongoing help with skills implementation. Participants in the step-down group continued with their individual therapists within the dialectical behavioral therapy framework. They met every other week for 90 minutes. A specific dialectical behavior therapy skill was highlighted in each group session. Unlike our standard skills groups, the step-down group had both male and female participants, most having completed the full cycle of the dialectical behavior therapy skills group at least twice.

To further address resource limitations, our final adaptation involved time limitations for the skills and consultation groups. The time allocation for the skills group was shortened to 90 minutes or two hours, depending on the individual therapists. Because of the number of clinicians involved in the program, we currently have two 60-minute weekly consultation groups, and therapists attend whichever one best fits their schedule. Skills group updates are sent to clinicians by confidential e-mail. Nonetheless, there is rarely sufficient time to address administrative issues, provide individual patient updates, and discuss clinical dilemmas.

Perceptions of the program

We sent patients and their therapists comparable surveys asking about their perceptions of the program. The clinicians received one survey for each patient they had treated. The patients and therapists rated the overall benefit each patient derived from dialectical behavior therapy on a scale from 1, no benefit, to 4, substantial benefit. Patients also rated their commitment to the program on a scale from 1, not at all, to 5, extremely. Last, therapists and patients rated their satisfaction with the program on a scale from 1, not at all, to 5, extremely. Twenty of the 27 individual therapists responded, providing information on 71 patients. Fifty-five of the 80 patients who had been asked to participate returned surveys, yielding a response rate of 69 percent.

Both sets of ratings indicated that 62 patients (60 percent) were perceived as or rated themselves as deriving at least some overall benefit. For the 46 patient-therapist pairs, the association between clinicians' and patients' ratings of patient benefit from dialectical behavior therapy was strong. Although dialectical behavior therapy was developed to treat female patients, ratings of benefit did not differ by gender.

Satisfaction with the program was high among both patients and clinicians. Thirty patients (55 percent) rated themselves as very or extremely satisfied. Patient satisfaction was strongly associated with patients' ratings and clinicians' ratings of patient benefit. No gender differences in satisfaction ratings were noted. All clinician responders reported that they were either very or extremely satisfied.

The duration of participation in therapy was strongly associated with clinicians' ratings of benefit and moderately associated with patients' ratings of benefit and of satisfaction. When duration in the program was controlled for, patients' level of commitment was a significant predictor of patients' ratings of benefit and satisfaction and accounted for an additional 31 percent of the variance in patients' benefit ratings and 28 percent of the variance in patient satisfaction ratings.

Conclusions

Before the development of our dialectical behavior therapy program, female veterans often experienced repeated hospitalizations in predominantly male inpatient wards or were referred to therapy groups comprising primarily men. Male patients with complicated trauma-related disorders were often considered treatment resistant (5,7,8) and were provided with primarily supportive therapies, because the expectation of treatment benefit was low. Although dialectical behavior therapy has not been a panacea, most providers and patients in our study reported that it provided at least some treatment benefit. Among patients with chronic and severe illness, even some benefit can result in a significant improvement in quality of life.

Adapting dialectical behavior therapy to any new clinical setting will require a dialectic approach to be successful—maintaining basic dialectical behavior therapy principles on one hand and modifying specific applications and expanding to new populations on the other. In our VA setting, specific issues we confronted in developing our program included cognitive impairment, literacy issues, diagnostic heterogeneity, and limitations on the availability of clinicians and of training funds. The adaptations we made to the standard dialectical behavior therapy model improved the feasibility of this approach in this setting without departing from it basic principles (15).

We initially thought we might have to modify the skills or their presentation to make them more palatable to male veterans. We were surprised to learn that these men were receptive to the skills in their current form. No gender differences were observed in perceived benefit or satisfaction with the program. Consistent with Linehan's formulation (11), instituting a dialectical behavior therapy program has been an intervention not just for patients but also for therapists, and we continue to learn from our patients and from each other.

The authors are affiliated with the mental and behavioral health patient service line of the Minneapolis Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 116B, One Veterans Drive, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55417 (e-mail, [email protected]). Marcia Kraft Goin, M.D., Ph.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 83 veterans enrolled in a dialectical behavior therapy programa

a Percentages do not sum to 100 because of comorbidity and rounding

1. Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, Public Law 102-585, §102-105, 38 USC, 1992Google Scholar

2. Hankin CS, Skinner KM, Sullivan LM, et al: Prevalence of depressive and alcohol abuse symptoms among women VA outpatients who report experiencing sexual assault while in the military. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:601-612, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Coyle B, Wolan D, Van Horn A: The prevalence of physical and sexual abuse in women veterans seeking care in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Military Medicine 161:588-593, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Herman JL: Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence: From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. New York, Basic Books, 1992Google Scholar

5. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ (eds): Effective Treatments for PTSD. New York, Guilford, 2000Google Scholar

6. Yen S, Shea MT, Battle CL, et al: Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190:510-518, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ: Guidelines for treatment of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13:539-555, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Frueh BC, Mirabella RF, Chobot K, et al: Chronicity of symptoms in combat veterans with PTSD treated by the VA mental health system. Psychological Reports 75:843-848, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Fontana A, Rosenheck R, Spencer H, et al: The Long Journey Home X: Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs: Fiscal Year 2001 Service Delivery and Performance. West Have, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs, 2002Google Scholar

10. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, et al: Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:235-239, 1993Link, Google Scholar

11. Linehan M: Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1993Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Changing patterns of care for war-related post-traumatic stress disorder at Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers: the use of performance data to guide program development. Military Medicine 164:795-802, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. McFall M, Fontana A, Raskind M, et al: Analysis of violent behavior in Vietnam combat veteran psychiatric inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:501-517, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Swenson CR, Torrey WC, Koerner K: Implementing dialectical behavior therapy. Psychiatric Services 53:171-178, 2002Link, Google Scholar

15. Linehan M: Commentary on innovations in dialectical behavior therapy. Cognitive and Behavior Practice 7:478-481, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar