Managerial and Environmental Factors in the Continuity of Mental Health Care Across Institutions

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the association of continuity of care with factors assumed to be under the control of health care administrators and environmental factors not under managerial control. METHODS: The authors used a facility-level administrative data set for 139 Department of Veterans Affairs medical centers over a six-year period and supplemental data on environmental factors to conduct two types of analysis. First, simple correlations were used to examine bivariate associations between eight continuity-of-care measures and nine measures of the institutional environment and the social context. Second, to control for potential autocorrelation, multivariate hierarchical linear models with all nine independent measures were created. RESULTS: The strongest predictors of continuity of care were per capita outpatient expenditure and the degree of emphasis on outpatient care as measured by the percentage of all mental health expenditures devoted to outpatient care. The former was significantly associated with greater continuity of care on six of eight measures and the latter on seven of eight measures. The environmental factor of social capital (the degree of civic involvement and trust at the state level) was associated with greater continuity of care on five measures. The degree to which non-VA mental health services were funded in a state was unexpectedly found to be positively associated with greater continuity of care. In multivariate analysis using hierarchical linear modeling, significant relationships with continuity of care remained for per capita outpatient expenditures, overall outpatient emphasis, and social capital, but not for non-VA mental health funding. A linear term representing the year was positively and significantly associated with six of the eight examined continuity-of-care measures, indicating improvement in continuity of care for the period under study, although the explanation for this trend over time is unclear. CONCLUSIONS: Several factors potentially under managerial control are associated with increased mental health continuity of care.

Continuity of care is widely regarded as an essential feature of care for individuals with severe mental illness (1,2,3,4,5), and it is increasingly one of the ways in which the quality of outpatient care is assessed (6,7,8). However, virtually no studies have examined mechanisms by which mental health administrators can enhance continuity of care. This issue can be investigated by examining the degree to which factors such as differential resource allocation, facility size, and use of performance measures for management evaluation are associated with continuity-of-care measures. The relevance of various strategies for improving continuity of care can be further investigated by comparing the association of factors that are under managerial control, or subject to managerial influence, with environmental factors that may also affect continuity but that are not under managerial control.

One difficulty in investigating these questions is that the concept of continuity of care is hard to operationalize because it has been used to refer to almost all aspects of service delivery (1). We conceptualize continuity of care in a narrower sense—as sustained contact, represented by three related concepts: regularity of care, as indicated by an evenness in the use of the services over time and the absence of a gap in care (6,9,10,11,); continuity of treatment across organizational boundaries—for example, through the transition from inpatient to outpatient services or between different types of outpatient services (7,12,13,14,15,); and provider consistency—that is, involvement with a limited number of consistently available providers (16,17,18). We developed eight measures of continuity of care that addressed these three concepts.

Administrative features of a health care system that could be subject to managerial influence or control include the allocation of resources, the degree of centralization, the use of performance monitoring systems, the mix of fixed assets and staff, and facility size. Professional practices within a health care system, such as clinical orientation or reliance on state-of-the-art technologies, may also affect continuity of care, but they are more difficult to measure and may be more difficult to change (19,20,21,22).

Environmental factors not under managerial control or subject to managerial influence may also affect continuity of care. Such factors include the availability of alternative sources of health care in the community, the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the population, and social capital, or the degree of civic involvement and trust existing in the regional culture (23,24).

In this study, we examined the relationship between eight measures of continuity of care, risk adjusted for differences in client characteristics, and nine institutional and environmental factors. We used a facility-level administrative data set containing performance information on the delivery of specialty mental health services at 139 Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers over a six-year period (1995 to 2000) and supplemental data on selected environmental factors.

Methods

Source of data and sample

All performance measures were derived from the VA's National Mental Health Performance Monitoring System (11). This data set includes information on the delivery of mental health services at 139 VA medical centers over six years, from 1995 to 2000. Data are derived from four VA administrative data sets: the patient treatment file, the outpatient care file, the patient encounter file, and the cost distribution report. The patient treatment file contains basic data on all episodes of VA inpatient care. The outpatient care file and the patient encounter file contain records of all outpatient services. The cost distribution report contains a comprehensive accounting of all VA health care expenditures.

Data on per capita expenditures by state mental health agencies are based on a report published by the Center for Mental Health Services (25). The measure of social capital was provided by Robert Putnam, Ph.D. (personal communication, December 2001), and makes use of national survey data from the Roper and DDB Needham life style surveys. Data on the per capita income of each state and the percentage of each state's population that were minorities were obtained from Census Bureau estimates from 1996 (26,27).

Measures

Continuity-of-care measures. We classified continuity-of-care measures in three domains: continuity across organizational boundaries, regularity of care, and provider consistency.

Continuity across organizational boundaries was examined with three measures: whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program received any mental health outpatient treatment during the first 30 days after discharge; whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program received any mental health outpatient treatment during the first six months after discharge; and whether a veteran who was discharged from an inpatient psychiatry program, and who also had a secondary medical diagnosis, received any medical outpatient care in the six months after discharge.

Regularity of care was examined with three measures. The first was the number of two-month periods in the six months after discharge from inpatient care in which a veteran had two or more outpatient mental health visits (range, 0 to 3). In contrast to the previous measures, which were based on an index inpatient stay, the two other regularity-of-care measures reflected continuity of outpatient services for severely mentally ill patients—that is, those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or affective psychosis—who had at least two outpatient mental health visits in the first six months of each fiscal year. These measures addressed the number of months during a six-month period in which a veteran had at least one visit (range, 0 to 6) and whether a veteran went six months without any outpatient mental health care—that is, whether the veteran dropped out.

Two composite indexes were used to examine provider consistency; these also pertained to severely mentally ill clients who had least two outpatient visits. The indexes were the Continuity-of-Care Index (COCI) and the Modified Modified Continuity Index (MMCI), which are based on the number of visits and the number of providers. The COCI uses the following formula (16):

where N equals the total number of visits and Nj is the total visits to the jth provider. This measure generates a continuity-of-care score from 0 to 1, where 1 represents more visits with fewer providers and 0 represents few visits with each of several providers. The second index, the MMCI, is calculated as follows (28):

This index takes a different approach to calculating a measure based on a scale of 0 to 1, but, as with the COCI, 1 represents more visits with fewer providers and 0 represents no visits.

All continuity-of-care measures were risk adjusted to minimize biases imposed by variability in sociodemographic characteristics across medical centers. Characteristics used for risk adjustment included age, race, gender, diagnosis, marital status, distance of residence to the nearest VA medical center, disability status, psychiatric diagnosis, and medical comorbidity. Further details of the analytic methods and risk factors are presented elsewhere (10,11).

Institutional factors. We hypothesized that several institutional factors assumed to be under managerial control would be associated with continuity of care.

First, we hypothesized that greater continuity would be associated with greater per capita expenditures on outpatient mental health care and more emphasis on outpatient care, as reflected by a higher percentage of total mental health expenditures on outpatient care. These measures were adjusted for inflation and local wage rates.

Second, we hypothesized that the degree of academic emphasis, as reflected by the proportion of mental health expenditures devoted to research and education, would be associated with less continuity of care, for two reasons: academic institutions have task priorities in addition to clinical care, and care is often provided by inexperienced and transient trainees.

Although the VA's National Mental Health Performance Monitoring System (11), beginning in 1995, circulated information on continuity-of-care measures, these measures had no official status until 1998, when they began to be used to evaluate the job performance of top VA administrators. A third hypothesis was that planning for the use of these measures as national performance indicators, which began in 1997, would be associated with greater continuity of care. Therefore we created a variable that had a value of 1 for the years 1997 to 2000 and a value of 0 for other years.

Finally, we hypothesized that larger hospitals, as measured by the number of full-time employees, would have less continuity of care because larger organizations are more complex and may have greater difficulty in coordinating services as needed to maintain high levels of continuity of care, particularly between inpatient and outpatient services.

Environmental measures. We examined two aspects of the environment of VA medical facilities. The first was the degree to which veterans had access to health services outside the VA. As an indicator of the availability of such resources we used the per capita expenditures by each state's mental health agency (25), which has been shown to be associated with reduced use of VA services (29,30). We expected that VA continuity of care would be lower in states in which more mental health resources were available.

The other environmental factor was social capital at the state level. Social capital, which refers here to the level of civic involvement or social trust, has been shown to foster greater cooperation in problem solving (23,31). We hypothesized that social capital would be associated with greater continuity of care. For example, a study of homeless people with severe mental illness in 18 U.S. cities showed that greater social capital was associated with greater system integration, greater likelihood of client contact with a public housing agency, and greater likelihood of becoming housed (24).

The social capital scale had 13 items, including the number of club meetings attended in the past year, the number of community projects worked on in the past year, the number of times volunteer work was done in the past year, general belief that other people are honest, and the proportion of adults in each state who voted in the 1988 and 1992 elections (23). The data came from telephone surveys administered to representative samples of civilians across the United States (23). These measures were standardized and averaged to generate a state-level measure.

Two other measures were used as controls for our analysis of social capital: the percentage of each state's population from ethnic minorities and the per capita income of each state. Putnam (23) has shown that more ethnically mixed and lower-income states have lower social capital, and our interest was in the effect of social capital independent of these factors.

Analysis

The analysis was performed in two steps. We first examined bivariate associations between each continuity-of-care measure and the nine predictors. Next we created multivariate models that included all the independent measures simultaneously. To control for potential autocorrelation, random effects were modeled for site with a compound symmetry covariance structure, thereby adjusting standard errors for the correlated nature of the data in these models. This technique is often referred to as hierarchical linear modeling (32). The PROC MIXED procedure of the SAS software system (33) was used for these analyses.

Results

Bivariate and multivariate relationships

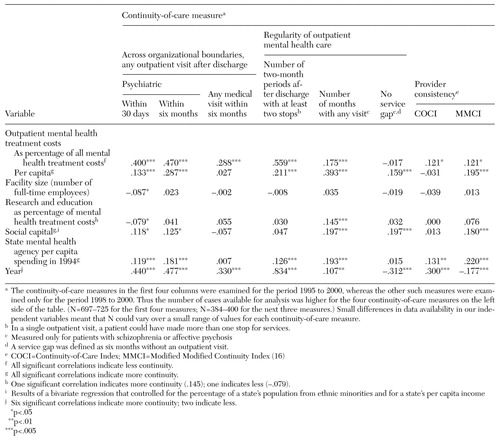

Correlations.Table 1 presents the results of bivariate correlations of the independent variables and continuity-of-care measures. The results reported for social capital are bivariate regressions in which the percentage of a state's population from ethnic minorities and the state's per capita income were also controlled for.

The two factors most strongly and consistently associated with continuity of care were per capita outpatient expenditures and the degree of outpatient emphasis, as measured by the percentage of mental health budget devoted to outpatient care. The first was significantly associated with greater continuity of care on six of the eight measures, and the second on seven of the eight measures. Social capital was found to have a significant association with greater continuity of care on all but one measure in each of the continuity-of-care domains, for a total of five measures.

In contrast to expectations, the degree to which non-VA mental health services were available in a state was associated with greater VA continuity of care on six measures. Last, six of eight analyses showed a highly significant relationship (p<.005) between a linear term representing the year of study and the continuity-of-care measures, indicating growing continuity of care over the period of study.

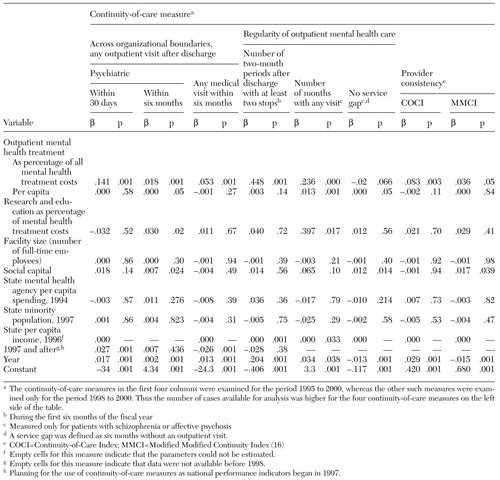

Random-effects models. As can be seen in Table 2, the most consistent result across the random-effects models was the association of outpatient emphasis with greater continuity of care: this factor was significantly related to all but one measure. Per capita outpatient expenditure was positively associated with three measures. Furthermore, social capital was significantly and positively associated with one of the continuity-of-care measures in each of the three domains. Contrary to our hypothesis, academic emphasis was positively associated with both the likelihood of an outpatient visit within six months after inpatient discharge and the number of months in which a visit was made by outpatients with schizophrenia or affective psychosis.

For two other time-sensitive independent measures we found inconsistent results. The variable of the year in which discussion began about the use of continuity-of-care indicators as performance indicators (1997 and after) was positively associated with the likelihood of a psychiatric outpatient visit within 30 days after discharge—the measure chosen as a performance indicator by VA headquarters—but negatively associated with the likelihood of a medical outpatient visit within six months after discharge. Finally, a linear term representing the year was positively and significantly associated with six of the eight continuity-of-care measures and negatively associated with two measures—the same result found in the bivariate analysis.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined correlates of continuity of care, some of which are subject to managerial control or influence and some of which are not. The strongest and most consistent associations were observed with two measures of funding for outpatient care: per capita dollar expenditures for mental health care and the proportion of total mental health funds spent on outpatient care. This finding is not surprising, because greater funding largely translates into greater staff time. Clinicians are more available to see patients and make efforts to contact them when they fail to show up. The fact that a greater emphasis on outpatient than on inpatient care over the study period is associated with improved continuity of care cannot be explained by simple resource availability. It may therefore reflect greater focus of managerial or clinical attention, or both, on outpatient care.

Facility size had little relationship to continuity of care, suggesting that greater organizational complexity does not necessarily preclude smooth coordination of service delivery. Academic emphasis, contrary to our hypothesis, was associated with greater continuity of care on several measures, suggesting that, despite their greater complexity and their commitment to multiple goals, teaching institutions may make efforts to model continuous care for their trainees. Thus both patterns of funding and academic emphasis were associated with greater continuity of care.

On the environmental side, the primary finding was that social capital was associated on several measures with greater continuity of care. Civic involvement, as measured by Putnam (23), addresses volunteerism, informal socializing, and social trust. Regional high levels of these attitudes may be associated with greater willingness to cooperate, coordinate, and communicate among clinicians, as among other citizens, resulting in greater clinical continuity of care.

State mental health funding was not independently associated with continuity of care, although on bivariate analysis it was positively associated with greater continuity of care. These findings were not expected, because several studies have shown that greater per capita spending on non-VA services is associated with less use of VA services by veterans (29,30). It appears that, although non-VA funding negatively affects the likelihood of using any VA services (29,30), it does not affect continuity of care among service users.

Finally, most measures indicated consistently increasing continuity of care over the years of this study. It is not clear whether this increase is attributable to managerial influence—for example, managers' efforts to improve continuity of care as part of improving the quality of all care—or to some unmeasured environmental influences—for example, professionals in general trying to improve continuity of care. The introduction of continuity of care as a national tool for evaluating managerial performance was inconsistently associated with these measures, although there may have been too few years of data to fully evaluate its effect.

Several methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. First, a large number of institutional and environmental factors were not examined because data were not available, such as staff turnover and professional mix at VA medical centers. Second, our analysis was cross-sectional rather than longitudinal; thus our results indicate the strength of associations only, limiting our ability to make causal inferences. Third, the factors addressed here were subject to the initiative of administrators at levels higher than the clinical level. More research is needed to identify clinical-level factors to improve continuity of care.

This study suggests that the amount and proportion of resources devoted to outpatient mental health services is the factor most strongly associated with continuity of care. Ours is one of the few studies to explore this topic and the first we are aware of to do so with multisite data from a large health care system. Further research is needed to validate and extend our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dianne DiLella, M.P.H., for her assistance with the VA's National Mental Health Performance Monitoring System from 1995 to 2000 and Jennifer Cahill, B.A., for data management.

The authors are affiliated with the Veterans Affairs (VA) Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the VA Medical Center in West Haven, Connecticut, and with the department of psychiatry at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Send correspondence to Dr. Greenberg at VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, NEPEC/207, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06514 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Correlations of independent variables and continuity-of-care measures in a multisite study of continuity of care in Veterans Affairs medical centers

|

Table 2. Random-effects models of the relationship of continuity-of care-indicators in a multisite study of continuity of care in Veterans Affairs medical centers

1. Bachrach L: Continuity of care for chronic mental patients: a conceptual analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:1449-1456, 1981Link, Google Scholar

2. Bachrach L: Continuity of care and approaches to case management for long-term mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:465-468, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Johnson S, Prossor D, Bindman J: Continuity of care for the severely mentally ill: concepts and measures. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:137-142,1997Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lehman A, Postrado L, Roth D, et al: Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation program on chronic mental illness. Millbank Quarterly 72:105-122, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Moos R, Finney J, Federman E, et al: Specialty mental health care improves patients' outcomes: findings from a nationwide program to monitor the quality of care for patients with substance use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 9:704-713, 2000Google Scholar

6. Bindman, J, Johnson S, Szmukler G, et al: Continuity of care and client outcome: a prospective cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:242-247, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Evaluation of the HEDIS behavioral health care measure. Psychiatric Services 48:71-75, 1997Link, Google Scholar

8. Tessler R: Continuity of care and client outcome. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:39-53, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Brekke J, Ansel M, Long J, et al: Intensity and continuity of services and functional outcomes in the rehabilitation of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:248-256, 1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck RA, Cicchetti D: A Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System for the Department of Veterans Affairs. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1995Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck R, Greenberg, G, DiLella D: National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 2000 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2001Google Scholar

12. Farrell SP, Blank M, Koch JR, et al: Predicting whether patients receive continuity of care after discharge from state hospitals: policy implications. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6:279-285, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Solomon P, Gordon B, Davis JM: Reconceptualizing assumptions about community mental health. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:708-712, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Sytema S, Micciolo R, Tansella M: Continuity of care for patients with schizophrenia and related disorders: a comparative south-Verona and Groningen case-register study. Psychological Medicine 27:1355-1362, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Tessler RC, Mason JH: Continuity of care in the delivery of mental health services. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:1297-1301, 1979Link, Google Scholar

16. Bice TW, Boxerman SB: A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Medical Care 4:347-349, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Pugh TP, MacMahon B: Measurement of discontinuity of psychiatric inpatient care. Public Health Reports 82:533-538, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Fontana A, Rosenheck R: Outcome Monitoring of VA Specialized Intensive PTSD Programs: FY 1996 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1997Google Scholar

19. Davies HT, Nutley SM: Developing learning organizations in the new NHS. British Medical Journal 320:998-1002, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Pettrigrew A, Ferlie E, McKee L: Shaping Strategic Change: Making Change in Large Organizations. London, Sage, 1992Google Scholar

21. Stein L: Persistent and severe mental illness: its impact, status, and future challenges, in Innovating in Community Mental Health: International Perspectives. Edited by Schulz R, Greenley JR. Westport, Conn, Praeger, 1995Google Scholar

22. Vestal KW, Fraliex RD, Spreier SW: Organizational culture: the critical link between strategy and results. Hospital and Health Services Administration 42:339-365, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

23. Putnam RD: Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, Simon and Schuster, 2000Google Scholar

24. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service delivery and community: social capital, service systems integration, and outcomes among homeless persons with severe mental illness. Health Services Research 36:691-710, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

25. Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ (eds): Mental Health United States 1998. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Pub No (SMA)-99-3285. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1998Google Scholar

26. US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census: Detailed State Projection Data Files. Population Electronic Product No 45. Washington, DC, Bureau of the Census, 1996Google Scholar

27. Per Capita Personal Income by State and Region, 1996; State Per Capita Personal Income Growth. News release. Washington, DC, US Department of Commerce, Economic and Statistics Administration, Bureau of Economic Analysis, April 1997Google Scholar

28. Magill M, Senf J: A new method for measuring continuity of care in family practice residencies. Journal of Family Practice 24:165-168, 1986Google Scholar

29. Rosenheck RA, Stolar M: Access to Public Mental Health Services: Determinants of Population Coverage. Medical Care 36:503-512, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Desai RA, Rosenheck RA: The interdependence of mental health service systems: the effects of VA mental health funding on veterans' use of state mental health inpatient facilities. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 3:61-68, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Olson M: The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1971Google Scholar

32. Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW: Hierarchical Linear Models. London, Sage, 1992Google Scholar

33. Littell RC, Milliken AG, Stroup WW, et al: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute Inc, 1996Google Scholar