Use of Schizophrenia as a Metaphor in U.S. Newspapers

Abstract

Research has identified misleading and stigmatizing popular beliefs about schizophrenia, but little is known about media images corresponding to these beliefs. Building on Susan Sontag's exploration of cancer in the 1978 book Illness as Metaphor, the authors hypothesize that "schizophrenia" is now more commonly misused. A total of 1,740 newspaper articles from 1996 or 1997 that mentioned schizophrenia or cancer were randomly selected and then coded for contextual and metaphorical use. Only 1 percent of articles that mentioned cancer used that illness in a metaphorical way, compared with 28 percent of the articles that mentioned schizophrenia. Results differed by newspaper but not by region. The authors suggest that these inaccurate metaphors in the media contribute to the ongoing stigma and misunderstandings of psychotic illnesses.

Stigmatizing references to schizophrenia deter treatment seeking and diminish the effectiveness of treatment (1). Metaphorical references to an illness can conjure up negative, disheartening associations (2) and, when commonly accepted, contribute to social rejection and degradation of well-being among persons who suffer from that illness (3).

In Illness as Metaphor, Sontag (4) posited that feared illnesses are used as metaphors—for example, tuberculosis in the 19th century and cancer in the 20th. Although subsequent empirical research has challenged Sontag's proposition about cancer, negative perceptions may also have improved with the dramatic medical advances that have occurred since Sontag called attention to the "mysteriousness" of the disease (5). Sontag's work suggests that misuse of metaphors is a reflection of ongoing stigmatizing beliefs; thus, metaphors involving mental disorders are likely to appear more often than those involving less stigmatized conditions.

We conducted an analysis to compare the use of the terms "schizophrenia" and "cancer" in a large sample of U.S. newspapers.

Media, stigma, and schizophrenia

The use of schizophrenia as a metaphor for split personality began with Bleuler's (6) conception of the disease as a mismatch between mood and thought, given its Greek roots "schizo" (split, schism, or separated) and "phrenos" (mind). The term "schizophrenia" was chosen for this disorder as a means of emphasizing that inappropriate affect is a dramatic symptom of the disorder, not to suggest a "splitting" of personality as meant by "multiple personality disorder" or, in today's nomenclature, "dissociative identity disorder." Nevertheless, the "splitting of mind" of schizophrenia remains commonly confused with splitting of personality.

References in the media to mental illness and to schizophrenia in particular are often associated with metaphorical references to split personalities. In studies of media in both Scotland (7) and the United States (8), mental illness has been linked to a split personality or to violence and odd behavior. A study of children's television programming concluded that "young viewers are being socialized into stigmatizing conceptions of mental illness" (9).

Methods

A stratified random sample of 1,802 articles was collected from the five U.S. newspapers with the highest daily circulation in 1996 to 1997 in each of the four regions identified in the LexisNexis database (www.lexisnexis.com)—Southeast, Northeast, Midwest, and West—as well as the two high-circulation national papers in the database, The New York Times and USA Today. At that time (May 1998), LexisNexis archived the full text of 108 general U.S. newspapers published in 40 states and the District of Columbia, including 16 of the top 20 circulating U.S. dailies. However, LexisNexis cannot be randomly sampled for specific articles within a defined date range. Thus, dates were randomly chosen until a target sample of about 1,000 articles was collected through use of the key terms "cancer," "cancerous," "schizophrenia," "schizophrenic," and "schizo." Because the term "cancer" was more frequent than the other terms, random selection of only five days was needed to collect 889 articles, whereas random selection of 174 days was required to collect 913 articles containing the term "schizophrenia."

Units of analysis were articles, but content coding was based on each sentence in which the key term was used. Review of the full text of an article resolved any potential ambiguities in proper assignment of codes. Key terms were coded into one of eight categories: metaphor, obituary, first person or human interest, medical news, prevention or education, incidental, medically inappropriate, and charitable foundation. Fifty-seven of the 913 articles that mentioned schizophrenia, but none of those that mentioned cancer, were too ambiguous to be coded into one of these defined categories and so were excluded from final comparisons. Coding was performed by a trained graduate assistant using QSR's NUD*IST program. In questionable cases, final decisions were made by consensus of the two psychiatrist coauthors. A random subsample of 100 articles was also coded by two psychiatry residents, who, although blinded to our findings, assigned the same primary codes to 95 percent of the articles.

Results

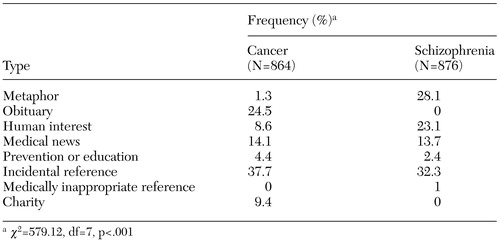

The frequencies of types of references to cancer and schizophrenia are listed in Table 1. Only 1 percent of the articles that mentioned cancer used the illness in a metaphorical way, compared with 28 percent of the articles that mentioned schizophrenia. Other differences discovered by coding our sample included the more frequent use of the term "schizophrenia" to describe a specific person and the more frequent use of the term "cancer" in articles about charity.

The range of metaphorical references to schizophrenia was striking. Typical examples include "a rival executive called ABC…'schizophrenic,' trying to be a family network some places, hip and cutting-edge in others" (Los Angeles Times); "the weather turns schizophrenic—81 degrees one weekend, sleet the next" (Houston Chronicle); "[the abortion rights position is] so schizophrenic that a baby can be thought of as a disposable chattel one day and a precious blessing the next" (Chicago Tribune); "[Los Angeles is] this unique, schizophrenic city" (Los Angeles Times); "the nation's schizophrenic perspective on drugs" (Los Angeles Times); "the schizophrenia of a public that wants less government spending, more government services and lower taxes" (Washington Post); "the schizophrenic actions of the Patriots…. 'We're the most Heckle and Jekyll team you've ever seen'" (Chicago Tribune); and, after a 192-point slide, "the [stock] market's acting schizophrenic" (Chicago Tribune). Rarely, the split between mood and thought was used as the basis of a metaphorical reference to schizophrenia: "Seattle went back to being the schizosonics, their emotions once again battling their talent for control of the franchise's great potential (Houston Chronicle). The metaphor rate varied overall from a high of 52 percent for USA Today to a low of 3 percent for the Buffalo News. The metaphor rate did not vary by region.

Discussion and conclusions

Given that 28 percent of the sampled articles used schizophrenia and related terms as metaphors, compared with 1 percent of articles that used cancer in this way, schizophrenia is indeed the new "illness as metaphor." Such imagery encourages further stigmatization and a popular orientation that discourages individuals from seeking treatment for their illness (10).

Of course, metaphorical use of these terms cannot simply be eliminated from media discourse, nor should it be. We can no more expect a disease to escape metaphorical use than we can any other term. However, we believe that the profession of psychiatry has an obligation to work to correct misleading metaphors and to encourage recognition of the positive achievements of persons with mental illness. Further research is needed to evaluate the sources of and trends in use of psychiatric terminology in the popular media as well as the ways in which inaccurate media images contribute to avoidance of treatment and resistance to diagnosis. For example, direct interviews of new patients and their families could further clarify the impact of such imagery on treatment.

Mark Twain once said that the difference between getting a word right and almost right is like the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. Getting the word "schizophrenia" almost right facilitates social unacceptability, contributing to a reluctance on the part of persons with schizophrenia to seek help for the condition. We look forward to the day when prevention and education—not metaphor and demonization—are the dominant messages carried to the public by the news media. The random sampling of America's newspapers suggests that we have a long way to go. Ongoing tracking of these inaccuracies may offer one measure of how our profession's advocacy and education affects the media and succeeds at reducing stigma toward our patients.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill.

Dr. Duckworth is affiliated with the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and with the department of psychiatry at McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Dr. Halpern is with the department of psychiatry at McLean Hospital. Dr. Schutt is with the department of psychiatry at Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Harvard Medical School, and with the department of sociology of the University of Massachusetts in Boston. Dr. Gillespie is with the department of sociology of Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. Send correspondence to Dr. Duckworth at Massachusetts Department of Mental Health, 25 Staniford Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Types of references to cancer and schizophrenia in U.S. newspapers

1. Warner R: Combating the stigma of schizophrenia. Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 10:12–17, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Link BG, Cullen FT, Frank J, et al: The social rejection of former mental patients: understanding why labels matter. American Journal of Sociology 92:1461–1500, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Clarkin JF, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: adverse effects of perceived stigma on social adaptation of persons diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatric Services 52:1627–1632, 2001Link, Google Scholar

4. Sontag S: Illness as Metaphor. New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978Google Scholar

5. Clow B: Who's afraid of Susan Sontag? or, the myths and metaphors of cancer reconsidered. Social History of Medicine 14:293–312, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bleuler E: The prognosis of dementia praecox: the group of schizophrenias, in The Clinical Roots of the Schizophrenia Concept: Translations of Seminal European Contributions on Schizophrenia. Edited by Cutting J, Shepherd M. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1987Google Scholar

7. Philo G, Secker J, Platt S, et al: The impact of the mass media on public images of mental illness: media content and audience belief. Health Education Journal 53:271–281, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Shain RE, Phillips J: The stigma of mental illness: labeling and stereotyping in the news, in Risky Business: Communicating Issues of Science Risk and Public Policy. Westport, Conn, Greenwood, 1991Google Scholar

9. Wilson C, Nairn R, Coverdale J: How mental illness is portrayed in children's television: a prospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:440–443, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al: On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:177–190, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar