Factors Associated With Rehospitalization Among Veterans in a Substance Abuse Treatment Program

Abstract

This study sought to determine predictors of rehospitalization among veterans in an inpatient substance abuse treatment program, many of whom had psychiatric disorders. A random sample of 600 veterans was interviewed at program entry about some factors not generally assessed as predictors. Information on rehospitalization in the two years after discharge was obtained from the databases of Veterans Affairs hospitals. Cox's proportional hazards model was used. Variables that were the strongest predictors were self-efficacy, childhood sexual and physical abuse, and religiosity. The results indicate that factors not usually investigated, such as attachment to family of origin, early physical and sexual abuse, and self-efficacy, are related to rehospitalization and should be further investigated.

Studies of predictors of readmission to Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers have typically examined factors that are not directly amenable to treatment, such as sociodemographic characteristics, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, and severity of substance abuse (1,2). The study reported here examined some variables that are not typically included in studies of rehospitalization—in particular, attachment to the family of origin—in order to identify predictors that may be more viable targets of planned intervention (3,4).

A person's attachment to early caregivers is theorized to be the reservoir from which emerge personality attributes that largely determine the experiences the person has later in life. Another attachment process that shapes personality traits is religiosity, or a person's spiritual beliefs, activities, and relationships (5). Loving attachments provide the security needed to explore one's sense of worth, efficacy, and identity; such exploration is essential to the resilience necessary to manage and overcome adversities encountered in life. Healthy attachments provide the template for positive social relations and the development of a support network.

Childhood physical abuse and sexual molestation are the result of unhealthy attachments, and these experiences foster adverse feelings, such as stress and depression, and thought disorders, or confused and disturbed thinking. Negative emotional states and disturbed thinking probably thwart a person's efforts to abstain from using alcohol or drugs and to function in a healthy way.

Methods

This retrospective study used data from a sample of 600 homeless Vietnam veterans, aged 46 to 65 years. Systematic random methods were used to select the sample from the population of inpatients in a substance abuse treatment program in a VA medical center in the Midwest. No differences were found in the demographic characteristics of the sample and the larger population of veterans who had been treated in the program. For example, 71 percent of both groups had been treated for substance abuse, and 40 percent of both groups had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

The study was approved by the VA institutional review board. After written informed consent was obtained, participants were interviewed on three separate days within two weeks of entering the domiciliary treatment program. The participants had entered the program directly after discharge from a 30-day inpatient detoxification intervention. The program integrated drug and mental health treatment, and its services focused on helping participants find and sustain employment and housing and achieve independent living.

The majority of measures were subscales from Hudson's Multi-Problem Screening Inventory (6). Twelve subscales were used. Three addressed childhood experiences—family attachment, physical abuse, and sexual abuse—and nine assessed current depression, fearfulness, stress, aggression, guilt, confused thinking, disturbing thoughts, suicidal thoughts, and self-esteem.

The 30-item Self-Efficacy Scale, the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and the 12-item Ego Identity Scale were used (7). A five-item scale of religiosity (5) addressed prayer, Bible study, discussion of religion, church attendance, and belief in a supernatural being.

Information about age, years of education, years of alcohol and other drug use, usual employment pattern over the past three years, the number of times treated for substance abuse, and the number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations was obtained from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (8).

Information about readmission of the participants to the hospital for psychiatric or substance abuse treatment within two years after discharge from the treatment program was obtained from the computer databases of all VA hospitals in the state in which the study was conducted and in the surrounding states.

Multicollinearity was checked with principal-components analyses, a correlation matrix, and tests of tolerance and the variance inflation factor. Tolerance is the proportion of the variance in a variable not associated with predictors already entered into the equation (1 minus r2) (9). On the basis of these tests, only certain scales from the Multi-Problem Screening Inventory were retained for analyses. Missing data was not a significant factor and did not amount to more than 3 percent of cases for any variable.

Results

Of the 600 veterans, 432 (72 percent), were readmitted to a hospital for substance abuse or psychiatric problems during the two-year follow-up period.

Cox's proportional hazards model was used because it is not based on any assumption about the nature or shape of the underlying survival distribution (10)—that is, about the proportion of participants who would remain unhospitalized and for how long.

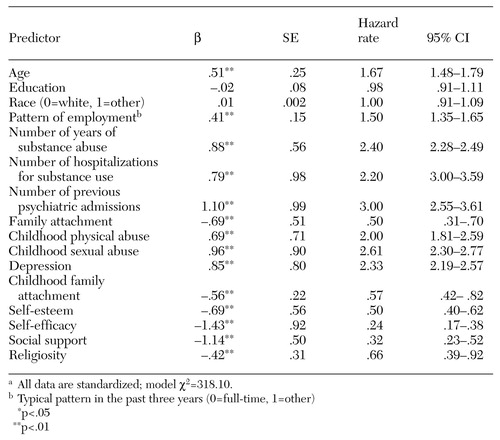

The hazard model indicated that the significant predictors of rehospitalization were self-efficacy, social support, number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations, sexual abuse before age 18, years of drug use, depression, number of times referred for drug treatment, self-esteem and physical abuse before age 18, age, and family attachment. Data are standardized, and thus the hazard rate in Table 1 represents the change in the readmission rate for a change in the predictor variable of one standard deviation.

Discussion

This study assessed hospital recidivism among homeless Vietnam veterans with substance use disorders, many of whom also had other psychiatric problems. The results showed that most of the variables examined as predictors were significantly associated with rehospitalization. The study is useful because it examined a wide range of factors over the life span. For example, the results suggest that early experiences in a person's family of origin may have long-term influences extending into adulthood. Insecure familial attachment and early physical and sexual abuse may instill deep feelings of despair and self-depreciation and inhibit the development of personal strengths such as self-efficacy. These adverse feelings and deficits in personal attributes may render persons vulnerable to depression and substance abuse (4). Assessment of factors such as unemployment, lack of social support, and lack of belief in an omnipotent being suggest that these vulnerabilities are related to rehospitalization (2). A history of drug abuse or of other psychiatric problems is also a well-documented predictor. This provides preliminary evidence that some factors that have not been extensively explored as predictors of rehospitalization, such as early physical and sexual abuse and self-efficacy, may be relatively strong predictors. However, a salient limitation of this study is that causality cannot be inferred because of the cross-sectional design. This problem is compounded by the reliance on self-reports about experiences that occurred before the age of 18. Responses could reflect problems of recall, including neurological damage, and present familial interactions. The modest correlations between the items on the scale that assessed attachment to the family of origin and the items on the ASI about present family relationships suggest that the participants made a distinction between past and present attachment to their families. However, the interrelationships between predictors need to be investigated in longitudinal studies.

The results suggest that treatment for this population should target residual feelings from childhood and attributions about the self in addition to substance abuse and psychiatric problems. Cognitive strategies aimed at bolstering self-efficacy and lessening depression that are used in conjunction with substance abuse and psychiatric treatment may help program participants secure and sustain employment. Viable social support networks, including strong family relationships, can supplement formal services in helping participants achieve and maintain independent living. This study provides some initial evidence that childhood experiences and present attributions about the self have a substantial influence on the ability of persons being treated for chronic substance abuse to live stably in the community.

Dr. Benda is professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas 72204 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results of a Cox's proportional hazards model of tenure in the community without rehospitalization over a two-year period among 600 veterans treated and released from an inpatient substance abuse treatment programa

a All data are standardized; model χ=318.10.

1. Piette JD, Baisden KL Moos, RH: Health Services for VA Substance Abuse and Psychiatric Patients: Utilization for Fiscal Year1996. Palo Alto, Calif, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1997Google Scholar

2. Murray MG, Anthenelli RM, Maxwell RA: Use of health services by men with and without antisocial personality disorder who are alcohol dependent. Psychiatric Services 51:380-382, 2000Link, Google Scholar

3. Bowlby J: Developmental psychiatry comes of age. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1-10, 1988Link, Google Scholar

4. Hanson RF, Spratt EG: Reactive attachment disorder: what we know about the disorder and implications for treatment. Child Maltreatment 51:137-145, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Benda BB: Religion and violent offenses among youth entering boot camp: a structural equation model. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 39:92-101, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Hudson WW: The MPSI Technical Manual. Tempe, Ariz, Walmer, 1990Google Scholar

7. Fischer J, Corcoran K: Measures for clinical practice, 2nd ed. New York, Free Press, 1994Google Scholar

8. Rosen CS, Henson BR, Finney JW, et al: Consistency of self-administered and interview-based Addiction Severity Index composite scores. Addiction 95:419-425, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Freund RJ, Wilson WJ: Regression Analysis: Statistical Modeling of a Response Variable. New York, Academic Press, 1998Google Scholar

10. Yamaguchi K: Event History Analysis. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1991Google Scholar