Smoking Cessation Approaches for Persons With Mental Illness or Addictive Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Persons with psychiatric illnesses are about twice as likely as the general population to smoke tobacco. They also tend to smoke more heavily than other smokers. This critical review of the literature identified 24 empirical studies of outcomes of smoking cessation approaches used with samples of persons with mental disorders. METHODS: The authors conducted searches of large health care and other databases for the years 1991 through 2001, using the key terms smoking, smoking cessation, nicotine, health/hospital/smoke-free policy, and psychiatry/ mental/substance abuse disorders. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: The majority of interventions combined medication and psychoeducation. Although the studies were not uniform enough to allow a meta-analysis, the recorded quit rates of patients with psychiatric disorders were similar to those of the general population. Clinicians could usefully devote more effort to smoking cessation in populations with mental illness or addictions.

Persons with psychiatric illnesses are about twice as likely as the general population to smoke tobacco (1), and those with schizophrenia are three or four times as likely (2,3). Alcohol and drug abuse are also strongly associated with a high rate of smoking, with prevalence estimates ranging from 71 to 100 percent (4,5,6). Compounding the high prevalence of smoking is the fact that individuals who are mentally ill or have substance dependence tend to smoke much more heavily than smokers in the general population (1).

Both neurobiological and psychosocial factors are thought to reinforce the use of nicotine in psychiatric populations (7,8). For many people with persistent mental illness, smoking is a major part of their daily routine and constitutes an activity that provides some structure to a day with few activities. Smoking also has long been considered an integral part of the psychiatric culture. Moreover, clinicians often believe that persons with mental illness are not able or willing to quit. Increasingly, however, health care facilities are implementing and enforcing smoking bans on their premises. These policies have heightened interest in outcomes of smoking cessation strategies for persons with mental illness or addictions.

Methods

We undertook a critical review of the literature to assess the impact of smoking cessation approaches on individuals with mental illness or addictive disorders. We conducted searches of large health care and other databases using the key terms smoking, smoking cessation, nicotine, health/ hospital/smoke-free policy, and psychiatry/mental/substance abuse disorders. The databases and the year spans used were MEDLINE, 1997-2000; CINAHL, 1990-2000; PsycINFO, 1990-2000; Best Evidence, 1991-2000; Healthstar, 1996-2000; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2000; Legal Trac, Bioethicsline, 1973-2000; Philosopher's Index, 1940-2000; and Dissertation Abstracts, 1990-2000.

Many of the papers that address smoking cessation treatment for this population are reviews or discussion papers or are based on anecdotal evidence. We included only studies that presented data on samples of people with diagnoses of specific mental illness or addictive disorders, with no restrictions as to methodology. Broader studies reporting symptomatic subgroups in their analysis, such as persons with depressive symptoms, were not included. Overall, 15 studies were excluded.

Results

Smoking cessation approaches

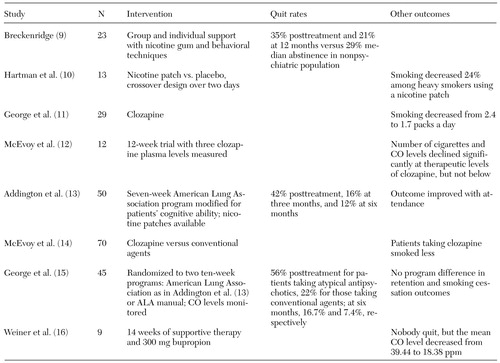

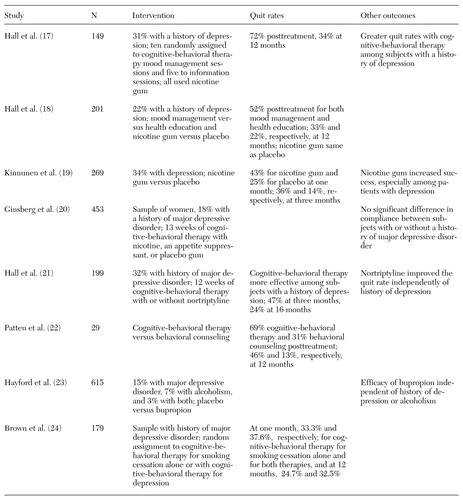

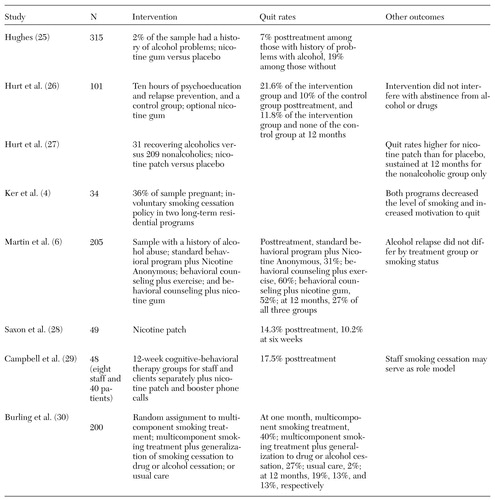

Twenty-four studies addressing the impact of smoking cessation strategies in samples of persons with mental illness or addictive disorders were reviewed. Eight included persons with schizophrenia, eight had substantial proportions of persons with depression, and eight focused on persons with addictive disorders. Tables 1, 2, and 3 list the studies (4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30), the interventions they used, their quit rates, and other outcomes of interest.

The majority of interventions used a combination of medication and educational and cognitive-behavioral approaches. Variables that affected outcome included number of cigarettes smoked per day, duration of previous quit attempts, history of alcohol or drug problems, and confidence about succeeding. The outcomes included quit rates, number of cigarettes smoked, and expired breath carbon monoxide levels. The time intervals for assessment varied from two days to 16 months.

The studies of persons with schizophrenia mostly involved small clinical samples. Posttreatment quit rates ranged from 35 percent to 56 percent. Two studies replicating one another's methods reported six-month overall quit rates of 12 percent (13), compared with 16.7 percent for patients taking atypical antipsychotics and 7.4 percent for patients taking conventional antipsychotics (11). The use of clozapine seems to reduce smoking.

The studies of persons with depression involved larger, media-recruited samples of smokers and may represent a wider range of morbidity than the schizophrenia group. Quit rates in these studies ranged from 31 percent to 72 percent at the end of treatment and from 11.8 percent to 46 percent at 12 months. The integration of cognitive-behavioral therapy with standard smoking cessation strategies appears to result in higher quit rates for persons with a history of major depression. In one study the efficacy of bupropion for smoking cessation was found to be independent of any history of depression or alcoholism (24).

The studies of persons with addictive disorders included both clinical and community samples. Quit rates ranged from 7 percent to 60 percent after treatment and from 13 percent to 27 percent at 12 months. When staff members quit smoking, it may provide positive role modeling for patients and increase staff willingness to provide smoking cessation support and intervention (29).

Discussion and conclusions

Studies of different approaches to smoking cessation for persons with mental illness or addictive disorders are not sufficiently uniform to allow meta-analysis. Diagnoses encompass a broad range of dysfunction, particularly in the samples of persons with depression and addictions, and the degree of dysfunction affects outcome. The studies also do not use a standard time interval between intervention and outcome assessment. In addition, using measures of the use of or abstinence from a substance without using measures of other domains of functioning may oversimplify outcome assessment.

Generally, although quit rates of psychiatric populations may be lower than those of nonpsychiatric populations, the reasons for quitting smoking, such as health concerns and costs, are comparable (31,32). Poorer outcomes for smoking cessation strategies among psychiatric patients may have been expected because of the suspected use of nicotine for self-medication in this population. Nevertheless, posttreatment and 12-month quit rates for psychiatric patients appear to be only marginally lower than those for nonpsychiatric samples (33).

These findings suggest that conventional attitudes about persons with mental illness being unable to quit smoking need to be modified. More resources should be devoted to cessation efforts for these populations, and clinicians should be more direct in asking patients about their interest in quitting smoking. Relatively brief interventions can increase the number of quitters, although smoking cessation tends to be a lengthier process for persons with mental illness. Staff training is a cost-effective investment.

The authors are affiliated with the Addiction Centre of the Calgary Health Region in Alberta, Canada. Dr. el-Guebaly and Dr. Currie are also with the department of psychiatry of the University of Calgary. Send correspondence to Dr. el-Guebaly, Foothills Hospital Addiction Centre, 1403-29 Street N.W., Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2N 2T9 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Findings of studies of smoking cessation approaches used with persons with schizophrenia between 1991 and 2001

|

Table 2. Findings of studies of smoking cessation approaches used with persons with depression between 1991 and 2001

|

Table 3. Findings of studies of smoking cessation approaches used with persons with addiction disorders between 1991 and 2001

1. Lasser K, Boyd W, Woolhandler S, et al: Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284:2606-2610, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. El-Guebaly N, Hodgins D: Schizophrenia and substance abuse: prevalence issues. Canadian Journal Psychiatry 37:704-710, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lyon E: A review of the effects of nicotine on schizophrenia and antipsychotic medications. Psychiatric Services 50:1346-1350, 1999Link, Google Scholar

4. Ker M, Leischow S, Markowitz I, et al: Involuntary smoking cessation: a treatment option in chemical dependency programs for women and children. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 28:47-60, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Patten C, Martin J, Owen N: Can psychiatric and clinical dependency treatment units be smoke-free? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 13:107-118, 1996Google Scholar

6. Martin J, Calfas K, Patten C, et al: Prospective evaluation of three smoking interventions in 205 recovering alcoholics: one-year results of project SCRAP-Tobacco. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:190-194, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ziedonis D, Kosten T, Glazer W, et al: Nicotine dependence and schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:204-206, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Dursun S, Kutcher S: Smoking, nicotine, and psychiatric disorders: evidence for therapeutic role, controversies, and implications for future research. Medical Hypotheses 52:101-109, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Breckenridge J: Smoking by outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:454-455, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hartman N, Leong G, Glynn S, et al: Transdermal nicotine and smoking behavior in psychiatric clients. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:374-375, 1991Link, Google Scholar

11. George T, Sernyak M, Ziedonis D, et al: Effects of clozapine on smoking in chronic schizophrenic outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:344-346, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

12. McEvoy J, Freudenreich O, McGee M, et al: Clozapine decreases smoking in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 37:550-552, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Addington J, el-Guebaly N, Campbell W, et al: Smoking cessation treatment for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:974-976, 1998Link, Google Scholar

14. McEvoy J, Freudenreich O, Wilson W: Smoking and therapeutic response to clozapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 46:125-129, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. George T, Ziedonis D, Feingold A, et al: Nicotine transdermal patch and atypical antipsychotic medications for smoking cessation in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1835-1842, 2000Link, Google Scholar

16. Weiner E, Ball MP, Summerfelt A, et al: Effects of sustained-release bupropion and supportive group therapy on cigarette consumption in patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:635-637, 2001Link, Google Scholar

17. Hall S, Munoz R, Reus V: Cognitive-behavioral intervention increases abstinence rates for depressive-history smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:141-146, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hall S, Sees K, Munoz R, et al: Mood management and nicotine gum in smoking treatment: a therapeutic contact and placebo-controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:1003-1008, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kinnunen T, Doherty K, Militello F, et al: Depression and smoking cessation: characteristics of depressed smokers and effects of nicotine replacement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:791-798, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Ginsberg J, Klesges R, Johnson K, et al: The relationship between a history of depression and adherence to a multicomponent smoking-cessation program. Addictive Behaviors 22:783-788, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hall SM, Reus VI, Munoz RF, et al: Nortriptyline and cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:683-690, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Patten C, Martin JE, Myers MG, et al: Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for smokers with histories of alcohol dependence and depression. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 59:327-335, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Hayford K, Patten C, Rummans T, et al: Efficacy of bupropion for smoking cessation in smokers with a former history of major depression or alcoholism. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:173-178, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Brown R, Kahler C, Niaura R, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:471-480, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hughes J: Treatment of smoking cessation in smokers with past alcohol/drug problems. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 10:181-187, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hurt R, Eberman K, Croghan I, et al: Nicotine dependence treatment during inpatient treatment for other addictions: a prospective intervention trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 18:867-872, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hurt R, Croghan I, Offord K, et al: Attitudes toward nicotine dependence among chemical dependency staff before and after a smoking cessation trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 12:247-252, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Saxon A, McGuffin R, Walker R: An open trial of transdermal nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation among alcohol-and-drug-dependent inpatients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 14:333-337, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Campbell B, Krumenacker J, Stark M: Smoking cessation for clients in chemical dependence treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:313-318, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Burling T, Curling A, Litini D: A controlled smoking cessation trial for substance-dependent inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:295-304, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Addington J, el-Guebaly N, Addington D, et al: Readiness to stop smoking in schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:49-52, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Lucksted A, Dixon LB, Sembly JB: A focus group pilot study of tobacco smoking among psychosocial rehabilitation clients. Psychiatric Services 51:1544-1548, 2000Link, Google Scholar

33. Wetter DW, Fiore MC, Gritz ER, et al: Smoking cessation clinical practice guidelines. American Psychologist 53:657-669, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar