Characteristics of New Clients at Self-Help and Community Mental Health Agencies in Geographic Proximity

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Self-help agencies are funded as adjuncts of, referral sources for, or alternatives to community mental health agencies. Little is known about how these two types of organization in geographic proximity interact, whom they attract as prospective clients, and what their clients bring to the service situation. The authors compared the characteristics and past service use of new enrollees of self-help agencies and community mental health agencies serving the same geographic area. METHODS: Interview assessments were conducted with 673 new users at ten pairs of self-help and community mental health agencies serving the same geographic areas. Client characteristics were evaluated with multivariate analysis of variance and chi square tests. RESULTS: Clients of community mental health agencies had more acute symptoms, lower levels of social functioning, and more life stressors in the previous 30 days than clients of self-help agencies. The self-help agency cohort evidenced greater self-esteem, locus of control, and hope about the future. Clients of self-help agencies had received more services from facilities other than self-help or community mental health agencies in the previous six months, and clients of self-help agencies who were not African American had more long-term mental health service histories. CONCLUSIONS: Although self-help and community mental health agencies both provide services to people with major mental disorders, community mental health agencies deliver primarily acute treatment-focused services, whereas self-help agencies provide services aimed at fostering socialization, mutual support, empowerment, and autonomy.

During the past 15 years, a revolution has occurred in the mental health system. Self-help agencies, incorporated as voluntary organizations, are managed and staffed by persons who have experienced hospitalization for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. These agencies do not focus solely on symptoms; rather, they address the social consequences of mental illness via mutual support and peer-helping models (1). Self-help agencies claim to serve individuals who have traditionally been underserved by community mental health agencies. They have been funded as adjuncts of, referral sources for, and alternatives to community agencies (2,3,4,5).

Little is known about how these two types of organization in geographic proximity interact, whom they attract as prospective clients, and what needs their clients bring to the service situation (1). Given that the two types of organization have the same target population, are there differences between clients who attend self-help agencies and those who use community mental health agency services? In this article we compare the demographic, clinical, and social characteristics as well as the service use histories of new clients of both types of agency.

Self-help agencies vary in program focus. They may serve mainly as drop-in centers or emphasize case management programs, outreach programs, consumer-operated businesses, employment and housing programs, or crisis services (6,7,8). Drop-in centers, the primary focus of self-help agencies in this study, offer social support and assistance. They involve high levels of client participation in organizational decision making and provide vocational opportunities ranging from volunteer roles to agency staff positions. Client staff gain meaningful work and act as role models. Compared with community mental health agency professionals, they are considered more empathic and more capable of engaging their peers in services (9). The drop-in center provides easy access to a nonthreatening environment that has concrete resources and offers social support, network-building opportunities, and day shelter. The setting requires minimal disclosure of personal information and allows clients to accept help at their own pace (10).

By contrast, community mental health agencies are frontline professional mental health treatment organizations for persons with serious mental illnesses. They provide inpatient and outpatient treatment, medication management, and case management services. In recent years, however, the constraints of managed care have imposed budget cuts on community mental health agencies. As studies have found little difference between consumer and professional case management efforts (11), cost-conscious mental health governing bodies are delegating socially based interventions to self-help agencies, leaving community mental health agencies to focus primarily on clinical interventions (12). This study addressed how this division of labor affects the characteristics of new clients who seek help in these organizations.

Methods

Participating agencies

Twenty-one organizations in six counties of the greater San Francisco Bay Area participated in the study. Pairs of community mental health and self-help agencies were chosen for their geographic proximity, and one community agency was paired with two self-help agencies. We sought to pair agencies that were within walking distance in urban settings and within a short ride in suburban or rural settings. The median distance between sites in a pair was 2.5 miles. This proximity allowed us to compare service use by a single local population in the two types of agency.

A self-help agency was defined as an organization with a client director, a governing board with a majority of client members, and an organizational structure in which clients hire and fire staff, including employed professionals. Self-help agencies provided client-operated services guided by a self-help ideology. Community mental health agencies were county mental health organizations.

Participating self-help agencies were open 5.3 days a week on average, serving about 43 clients a day. They all emphasized the exchange of mutual support between members, and all were characterized by a high degree of participatory governance. Common service elements included peer support groups, material resources, drop-in socialization, and direct services. The range of direct services the agencies provided included help in obtaining survival resources, such as food, shelter, and clothing; money management; counseling; payeeship services; case management; peer counseling; and provision of information or referral. Self-help agencies provided physical space for socialization and the development and maintenance of peer support networks. They also offered opportunities for involvement in local, state, and national advocacy efforts (13).

The participating community mental health agencies provided outpatient mental health services for the mentally disabled population, who we believed had similar characteristics to the clients of the paired self-help agency sites. Community mental health agency assistance included assessment, medication review, individual and group therapy, case management, and referral.

Sample

Between 1996 and 2000, all new clients of the selected self-help and community mental health agencies were asked to participate in the study. Clients were considered new if they had not received services in such an organization during the six months before they entered the agency.

A total of 787 clients were asked to participate. Of these, 673 (86 percent) agreed to participate—226 from self-help agencies and 447 from community mental health agencies. No significant differences in gender, ethnicity, and housing status were found between clients who agreed to participate and those who refused. The refusal rates at community mental health agencies and self-help agencies were similar (14 percent and 15 percent, respectively). IRB approval was obtained for all study procedures, and all study participants provided informed consent.

Assessment

Interviews were conducted by former mental health clients and professionals trained at the Center for Self-Help Research in Berkeley, California.

Two interview schedules were used that had been pretested, respectively, with a sample of 310 long-term users of self-help agencies in northern California (14) and with a pretest sample of 30 community mental health agency clients. The first interview included questions about demographic, housing, and income characteristics and included measures of functional status and of empowerment and attitudes toward self and others that are central to the self-help movement's objectives (15,16). Information about lifetime history of disability and service use was also obtained.

Validated measures of psychological disability and of functional status included the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (17), which runs from 20 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater depression; the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (18), which runs from 24 to 168, with higher scores indicating greater severity of psychiatric symptoms; the Health Problems Checklist (19), which runs from 1 to 35, with higher scores indicating more health problems; and the Independent and Assisted Social Functioning Scales (ISFS and ASFS, respectively) (20,21), which run from 75 to 336 and from 36 to 180, with higher scores indicating better social functioning. Validated measures of empowerment and attitudes toward self and others included the Personal Empowerment Scale (22), which runs from 26 to 83, with higher scores indicating a greater sense of being empowered; the Hope Scale (23), which runs from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater hope; the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (24,25), which runs from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater self-esteem; and the Locus of Control Scale (26), which runs from 18 to 49, with higher scores indicating greater locus of control. The second interview included the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version IV (DIS-IV).

Analyses

Frequencies and means were computed for the sample's descriptive characteristics, and statistical tests were conducted to assess group differences on summary measures. Chi square analysis was used to evaluate differences between self-help and community mental health agencies in the distribution of clients' diagnoses.

The SPSS GLM multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) procedure was used to evaluate mean differences between groups on current psychological, functional, empowerment, and cumulative measures of health symptoms, stressful life events, and services received from sources other than self-help or community mental health agencies during the six months preceding enrollment. The MANOVA included 11 dependent variables and two independent variables—agency of enrollment (self-help agency was coded 1 and community mental health agency was coded 0) and ethnicity (African American was coded 1 and other was coded 0)—as well as the interaction of these factors.

The possibly unique experience of African Americans was explored because of this group's high risk of receiving inappropriate or inadequate services (2). Observed mean differences were considered significant at the .05 level after Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Statistical assumptions for the procedure were met. Although Box's test for the equality of covariance matrices was significant, the p value was not small enough to be of concern (p=.04), given the robustness of the test (27). None of Levene's tests for equality of error variances were significant, with the exception of that for the services variable. To meet the normality assumptions, the three cumulative measures—the numbers of stressful life events, of services, and of health symptoms—were entered into the equation in log form.

Results

Demographic, housing, and income characteristics

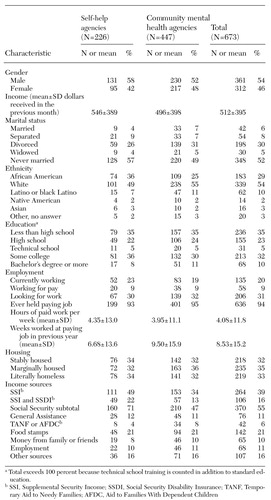

Table 1 presents data on the demographic, housing, and income characteristics of the study sample as a whole and by agency. Both the mean and the median age of respondents was 39 years. More than half the sample was male (54 percent); 52 percent had never married; 35 percent had less than a high school education, and 32 percent had some college. More than half of the respondents were Caucasian (54 percent), 29 percent were African American, 10 percent were Latino, 3 percent were Asian, 2 percent were Native American, and 3 percent were of other ethnicities.

Thirty-three percent of the sample were literally homeless at the time of the interview—that is, living in shelters, in cars, or on the streets. Thirty-two percent were in stable housing, and 8 percent were receiving Section 8 housing support. The remaining 35 percent were "marginally housed"—that is, they currently had housing but had a history of homelessness in the previous five years. Overall, 62 percent reported having been homeless during at least part of the previous five years, with a median time homeless of 14 months.

The mean previous month's income for the sample was $512, and the median was $609. The primary source of income for 55 percent of the sample was Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI).

Inspection of Table 1 reveals few differences between clients of self-help agencies and of community mental health agencies in demographic, housing, and income characteristics. The most notable differences are in source of income. Nearly three-quarters (71 percent) of clients of self-help agencies received their income from Social Security, compared with one-half (47 percent) of community mental health agency clients. Moreover, twice as many community mental health agency clients received their income from Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) (8 percent versus 4 percent). These differences are a matter of degree, since most clients are supported by SSI and few are supported by TANF, and total monthly income differed by only $50.

Diagnostic characteristics

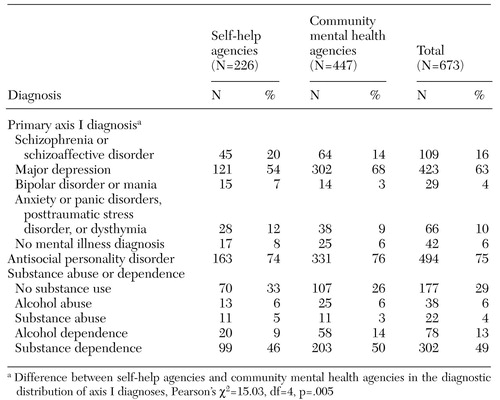

Table 2 summarizes the diagnostic characteristics of the sample. Eighty-five percent of the sample met DSM-IV criteria for an active disorder the previous year. Sixty-three percent met criteria for major depression, 16 percent for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, 10 percent for anxiety disorders, panic disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, or dysthymia, and 4 percent for bipolar disorders.

The observed statistically significant difference in the distribution of axis I diagnoses for the two groups (χ2=15.03, df=4, p=.005) seems attributable largely to the difference in the numbers of clients suffering from major depression (68 percent compared with 54 percent). This distributional difference was slightly less among African Americans, among whom 58 percent in community mental health agencies had major depression, compared with 47 percent in self-help agencies.

The within-agency proportional representation of individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorder varied considerably by race; for African American clients it was 20 percent in the community mental health agencies and 15 percent in the self-help agencies, compared with 12 percent and 23 percent, respectively, for persons in the other racial categories.

Substance dependence was common in this sample. Thirteen percent of the clients had a diagnosis of alcohol dependence and 49 percent of another substance dependence. Although no differences in the diagnostic distribution of substance dependence were apparent across the two settings, at the community mental health agencies a greater proportion of clients who were not African American had a diagnosis of substance dependence (63 percent, compared with 53.7 percent African American), whereas at the self-help agencies the proportion of those with a substance dependence diagnosis was about equal between these two racial categories (52.3 percent non-African American, compared with 56.2 percent African American).

Psychosocial function and attitudinal characteristics

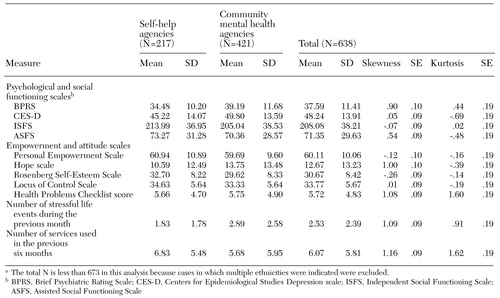

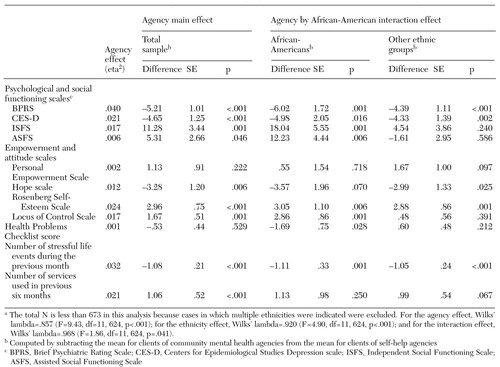

MANOVA was used to evaluate mean differences between groups on psychological, functional, and empowerment measures and in cumulative measures of health symptoms, stressful life events, and services received in the previous six months from sources other than self-help or community mental health agencies. Client ethnicity—African American versus others—and its interaction with choice of agency were taken into account. Table 3 summarizes the distributions of these variables.

The main effects and interaction effect were significant. As Table 4 shows, all psychosocial function measures showed significant between-group differences, with the exception of the Personal Empowerment Scale. Clients of community mental health agencies evidenced more acute symptoms and had lower scores on independent social functioning measures. Clients of self-help agencies evidenced greater self-esteem, hope, and locus of control. This pattern was even more pronounced among African Americans, although the measure for hope was not statistically significant. In the non-African American group no functional differences were significant. The observed significant interaction seems to be accounted for by the pronounced differences in functioning between African Americans in the two types of agencies and the absence of such differences in the non-African American group.

Characteristics of health and life stressors

Clients in the sample reported a mean±SD of 5.7±4.8 health problems in the previous six months. As Table 4 indicates, no significant overall difference was observed between the self-help and community mental health agency groups on the physical health status total score. However, African Americans at the self-help agencies were healthier than their counterparts at the community mental health agencies.

Eighty-five percent of the sample reported experiencing a major life stressor during the previous year, and 80 percent had experienced such events during the previous month (data available from the authors). The MANOVA indicated that clients of the self-help agencies experienced significantly fewer stressors within the previous month (about two on average) than clients of the community mental health agencies group (about three on average).

History of service use

The sample reported high use of services from sources other than self-help and community mental health agencies during the previous six months. At least 71 percent and 51 percent of clients of self-help agencies and of community mental health agencies, respectively, used survival services; at least 28 percent and 30 percent, respectively, used advocacy services; at least 12 percent and 9 percent used vocational services; at least 23 percent and 22 percent used housing assistance; at least 50 percent and 42 percent used living skills; and at least 65 percent and 27 percent used social activities. These percentages were calculated by using the highest figure reported for a given service within a category.

Such services included survival, advocacy, and vocational services, housing assistance, and help with or training in living skills (data available from the authors). The MANOVA indicated that clients of the self-help agencies had used significantly more services than clients of the community mental health agencies.

A majority of clients in the sample had experienced psychiatric hospitalization, with 68 percent reporting that they had been hospitalized at some time in their lives and 59 percent in the past year. Clients of the self-help agencies reported having been hospitalized during the previous ten years more frequently than clients of community mental health agencies (mean±SD, 6.85±12.2 compared with 4.28±6). This result was attributable to the large number of hospitalizations among non-African American clients at the self-help agencies, with a mean±SD of 8.2±13.9 hospitalizations in the past ten years, compared with 3.1±2.6 among African Americans (ANOVA interaction of agency by African American, F=6.9, df=3, 372, p=.009).

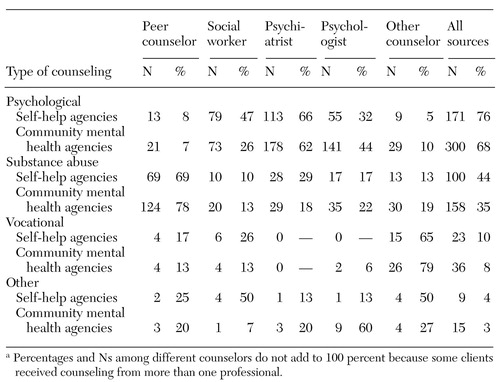

As Table 5 shows, clients in the sample had used counseling services extensively in the past. Clients at the self-help agencies were more likely to be currently receiving counseling of any type than clients at the community mental health agencies (55 percent 33 percent, respectively; χ2=28.72, df=1, p<.001), again a trend more pronounced among those who were not African American (58 percent versus 32 percent) than among African Americans (49 percent compared with 38 percent).

Discussion

Clients of both the self-help agencies and the community mental health agencies are poor and have major mental health problems. Only 6 percent of the sample did not have an active DSM-IV diagnosis, and for many of the clients their problems were complicated by substance dependence and homelessness. Thus, even though these clients were new to the agencies in our study, few of them were new to help seeking from public social and mental health service organizations.

The two groups differed in the nature of their problems and their current coping. Clients of the community mental health agencies were more acutely troubled with their mental health problems, as evidenced by their symptom scores on the CES-D and the BPRS. They had greater problems coping socially, as reflected in the greater number of stressful life events they experienced and in their lower functional status scores on the ISFS and the ASFS.

Among African Americans, the lower functional status and more acute symptoms of clients of community mental health agency compared with clients of self-help agencies seems attributable to the greater presence of African Americans with schizophrenia in the community mental health agency group. Despite these differences, however, the community mental health agency group may have a better prognosis, or may be less established in their illness career than clients of the self-help agencies who are not African American, as they tend to have had fewer inpatient experiences in the previous ten years.

Clients of the community mental health agencies worked more weeks for pay in the previous year than those of the self-help agencies, and the latter group was more likely to rely on SSI or SSDI for support. Both groups, however, are vocationally troubled.

It would appear that the community mental health agency clients are more likely to need crisis-oriented or stabilizing services, whereas clients of the self-help agencies require more long-term maintenance and socialization services. Interestingly, a history of assistance from social workers seems to be associated with greater use of self-help agencies, and experience with psychologists seems to be associated with greater use of community mental health agencies.

Self-help agency participants bring to the helping situation greater hope, self-esteem, and perceived control over their circumstances. While this may be due to the less acute nature of their conditions, it also may reflect a greater readiness to engage with their problems, which would contribute to the relative success reported by self-help agencies (6).

In emphasizing the differences between these client groups, we should not overlook their similarities. At least half of both groups, regardless of ethnicity, suffered from major depression, had undergone psychiatric hospitalization in the previous year, were literally homeless or marginally housed, required assistance with obtaining meals and groceries, and had experienced a major life stressor in the previous month. The type of agency clients enrolled in was only modestly related to the differences observed between the two groups, accounting for only 14.3 percent of the variance in our 11 summary indicators of psychosocial function, attitude, health, stressful life events, and use of services from other sources. Thus our study can be said to describe tendencies in client profiles observed between the agencies rather than distinct client groups with unique needs.

Conclusions

In our sample, new users of services of self-help and community mental health agencies had extensive involvement with multiple service systems, and many may be continuously cycling through the mental health system. Clients who came to the community mental health agencies were more likely to be in the acute phase of their conditions, whereas those coming to the self-help agency were seeking primarily psychosocial assistance.

Accordingly, community mental health agencies should focus on addressing acute problems from a multiservice perspective, allowing self-help agencies to provide ongoing support services and advocacy for clients with a long history of mental health problems. However, it is critical that community mental health agencies recognize and appreciate the role of self-help agencies in long-term maintenance and support, perhaps through more formalized referral networks to self-help agency services. While many services cannot be provided by the community mental health agencies because of time, cost, and caseload limitations, clients should not go without these services when they are available at nearby self-help agencies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grant RO1-MH-37310 and training grant MH-18828 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Maureen Lahiff, Ph.D., for statistical consultation and advice.

Dr. Segal is professor at the University of California, Berkeley, Dr. Hardiman is assistant professor at the University at Albany, State University of New York, and Dr. Hodges is assistant professor at the University of Missouri in Columbia. Send correspondence to Dr. Segal, Mental Health and Social Welfare Research Group, School of Social Welfare, 120 Haviland Hall (MC# 7400), University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-7400 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic, housing, and income characteristics of clients of self-help agencies and community mental health agencies

|

Table 2. Diagnostic characteristics of clients of self-help agencies and community mental health agencies

|

Table 3. Summary measures of current client psychosocial functioning, empowerment, health, stressful life events, and service use among clients of self-help agencies and community mental health agencies (N=638)a

a The total N is less than 673 in this analysis because cases in which multiple ethnicities were indicated were excluded.

|

Table 4. MANOVA pairwise comparisons for summary measures of current client psychosocial functioning, empowerment, health, stressful life events, and service use among clients of self-help agencies and community mental health agencies (N=638)a

a The total N is less than 673 in this analysis because cases in which multiple ethnicities were indicated were excluded. For the agency effect, Wilks' lambda=.857 (F=9.43, df=11, 624, p<.001); for the ethnicity effect, Wilks' lambda=.920 (F=4.90, df=11, 624, p<.001); and for the interaction effect, Wilks' lambda=.968 (F=1.86, df=11, 624, p=.041).

|

Table 5. History of counseling and type of professional providing counseling among clients of self-help agencies (N=226) and community mental health agencies (N=446)a

a Percentages and Ns among different counselors do not add to 100 percent because some clientsreceived counseling from more than one professional.

1. Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, et al: Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 6:165-187, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999Google Scholar

3. Nikkel RE, Smith G, Edwards D: A consumer-operated case management project. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:577-579, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Kaufmann CL, Ward-Colasante C, Farmer J: Development and evaluation of drop-in centers operated by mental health consumers. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:675-678, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

5. Mowbray CT, Tan C: Consumer-operated drop-in centers: evaluation of operations and impact. Journal of Mental Health Administration 20:8-19, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Long L, Van Tosh L: Program descriptions of consumer-run programs for homeless people with mental illness. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1988Google Scholar

7. National Resource Center on Homelessness and Mental Illness: Self-Help Programs for People Who Are Homeless and Mentally Ill. Delmar, NY, Policy Research Associates, 1989Google Scholar

8. Van Tosh L, del Vecchio P: Consumer/survivor-operated self-help programs: a technical report. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (in press)Google Scholar

9. Mowbray CT, Moxley DP, Thrasher S, et al: Consumers as community support pro-viders: issues created by role innovation. Community Mental Health Journal 32:47-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Segal SP, Baumohl J: The community living room. Social Casework 66:111-116, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Draine J: The efficacy of a consumer case management team:2-year outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:135-146, 1995Google Scholar

12. Allness D, Knoedler W: Recommended PACT standards for new teams. Available at www.nami.org/about/pactstd.htmlGoogle Scholar

13. Chamberlin J: The ex-patient's movement: where we've been and where we're going. Journal of Mind and Behavior 11:323-336, 1990Google Scholar

14. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Characteristics and service use of long-term members of self-help agencies for mental health clients. Psychiatric Services 46:269-274, 1995Link, Google Scholar

15. Rappaport J: Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology 15:15-22, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Chavis DM, Wandersman A: Sense of community in the urban environment: a catalyst for participation and community development. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:55-81, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Overall J, Gorham D: The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Segal SP, Gomory T, Silverman C: Health status of homeless and marginally housed users of mental health self-help agencies. Health and Social Work 23:45-52, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Segal SP, Aviram U: The Mentally Ill in Community-based Sheltered Care. New York, Wiley, 1978Google Scholar

21. Segal SP, Kotler PL: Personal outcomes and sheltered care residence: ten years later. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 63:80-91, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215-227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Zimmerman MA: Toward a theory of learned hopefulness: a structural model analysis of participation and empowerment. Journal of Research in Personality 24:71-86, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Rosenberg M: Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1965; reprinted in Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes, vol 1, edited by Robinson J, Sharer P, Wrightsman L, San Diego, Academic Press, 1991Google Scholar

25. Fleming JS, Courtney BF: The dimensionality of self-esteem: II. hierarchical facet model for revised measurement scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48:1490-1502, 1984Google Scholar

26. Dutteiler PC: The internal control index: a newly developed measure of locus of control. Educational Psychological Measurement 44:209-221, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 3rd ed. New York, HarperCollins, 1996Google Scholar