Mediation of Employment Discrimination Disputes Involving Persons With Psychiatric Disabilities

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to determine whether persons with psychiatric disabilities who filed employment discrimination complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) were referred to the EEOC's mediation program with the same frequency as ADA claimants with other disabilities. The extent to which employers agreed to engage in mediation with claimants and the extent to which claimants benefited from participating in the mediation program were also examined. METHODS: The data included all 23,759 ADA charges filed with the EEOC from January 1, 1999, through June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000. Percentages of mediation rates were computed, and chi square tests were conducted to test for differences between categories. RESULTS: Individuals with employment discrimination complaints based on psychiatric disabilities were slightly but significantly less likely to be referred by the EEOC to mediation than were individuals with other types of disabilities. Moreover, employers were significantly less willing to mediate with claimants who had psychiatric disabilities than with those who had nonpsychiatric disabilities. Once employers agreed to participate in mediation, however, the majority of cases were settled. No significant differences in settlement rates were found between cases with claimants who had psychiatric disabilities and cases with claimants who had other types of disabilities. CONCLUSIONS: The EEOC's mediation program has been a remarkably successful development and has the potential to provide effective case resolution services to thousands of EEOC claimants. However, the agency should educate employers and EEOC investigators alike that many people with psychiatric disabilities can work productively and participate in mediation successfully.

The United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is responsible for enforcing Title I (the employment provisions) of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). It is also responsible for enforcing several other federal laws prohibiting job discrimination. Congress, however, has never given the EEOC the resources it has needed to properly investigate cases brought before it. Consequently, the agency has always struggled with many more complaints than it can properly handle.

In an effort to make the most of its limited resources, the agency is making increasing use of mediation—an alternative to more formal, adversarial dispute resolution approaches. During mediation, disputants meet together with a neutral third party to discuss their differences and develop their own solutions (1,2). The mediator has no decision-making authority. Rather, his or her role is to help disputing parties develop options for a mutually acceptable resolution (3).

During the past several decades, mediation has played an increasingly important role in resolving disputes. It has long been an important part of labor-management and international relations (4). More recently, it has been used successfully in situations as diverse as bankruptcy (5), neighborhood feuds (6), police interventions (7), family conflicts and divorce (8,9,10), and environmental disputes (11).

Mediation offers many advantages; it is usually a less costly, less time-consuming, and less frustrating method of resolving disputes than litigation or other formal approaches (1,2,4,5). However, it also has disadvantages. Perhaps the most significant is that power imbalances between the disputants can result in smaller benefits for the less powerful parties, if agreements are reached at all (12,13,14,15).

The EEOC's mediation program is one of this country's largest employment mediation programs (3). The agency began pilot-testing mediation in 1991. Although most of its larger offices subsequently adopted some form of mediation, there had been no separate funding or consistent institutional support for mediation within the agency. Then, in the EEOC's fiscal year 1999 budget, Congress earmarked $13 million for mediation. Since then, mediation has served as a major adjunct to the charge process.

Through a contract with the EEOC, an evaluation was recently conducted of its mediation program (3). Mediation participants were asked about their satisfaction with the program. According to the evaluators, both charging parties and employers "gave high marks to the various elements of the EEOC's mediation program." Although useful, the evaluation did not differentiate between ADA complainants with psychiatric disabilities and complainants with other types of disabilities.

Indeed, there is very little published research examining mediation with individuals with psychiatric disabilities. The notable exception is a survey of the extent to which state mental health agencies, protection and advocacy programs, and other groups have adopted mediation and in what situations (2). The survey found that both mental health agencies and protection and advocacy programs have been experimenting with mediation and that mediation has been used to resolve disputes between clients and agencies, between consumers and state hospitals, and between individual consumers. Survey respondents believed that mediation is a fairer dispute resolution method than more formal adversarial processes.

In an essay on mediation in disputes involving persons with mental illness, Mazade and coauthors (1) identified as a major barrier the assumption that persons with mental illness lack the capacity to engage in mediation. We found evidence of this assumption during visits to EEOC field offices for our ongoing research on the ADA Title I enforcement process: several EEOC staff reported that they do not refer individuals with psychiatric disabilities to mediation because "they become too emotional."

We have been studying the Title I enforcement process since 1995. Previously, we presented findings about the regular administrative charge process and its consequences for Title I complainants with psychiatric and other disabilities (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25). In this study we compared ADA claimants who had psychiatric disabilities with claimants who had other types of disabilities regarding the extent to which the EEOC offered them the opportunity to participate in mediation, the extent to which employers agree to mediate with claimants, and the extent to which claimants benefit from participating in the mediation program.

Methods

The data

The EEOC's charge data system records all offers to claimants and employers to participate in mediation, all responses to offers, and all mediation outcomes. After receiving approval from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Medical School's institutional review board, we obtained data under the Freedom of Information Act on all Title I charges that were referred to and closed by the EEOC's mediation program between January 1, 1999, and September 30, 2000.

The population

Title I provides protection for persons with physical and mental impairments. It also covers substance abuse impairments, although individuals currently engaging in the use of illegal drugs are not covered. Also, employers may prohibit the use of alcohol at the workplace and require that employees not be under the influence of alcohol in the workplace.

For the purposes of this study, and in line with the accepted classification of substance-related disorders as a psychiatric condition (26), we grouped disabilities into substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders and compared them with all other impairments. In the EEOC charge process, people with "nonvisible" impairments associated with substance use or other psychiatric disorders self-report their impairment or diagnosis. The EEOC's charge data system contains five psychiatric disability designations: anxiety disorder, depression, manic-depressive disorder, schizophrenia, and "other emotional impairments." It contains two substance abuse designations: alcohol abuse and chemical abuse.

The data set used for the analysis included data on the 23,759 ADA charges filed with the EEOC from January 1, 1999, through June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000. Of these, 758 involved anxiety disorders, 1,825 involved depression, 510 involved manic-depressive disorder, 123 involved schizophrenia, 673 involved "other emotional impairments," 285 involved alcohol abuse, 128 involved chemical abuse, and 20,075 involved other disability designations. The total number of impairments adds up to more than the total number of charges in our data set because some charges involved individuals who reported more than one type of disability.

Analysis

We report simple percentages of mediation rates. Chi square tests of independence were conducted for comparisons between types of psychiatric disabilities and types of substance abuse. Chi square tests were also used to assess for differences between the three larger categories: psychiatric cases, substance abuse cases, and nonpsychiatric, non-substance abuse cases. In addition to using significance tests, we also examined the magnitude of the differences and the extent to which these differences were meaningful or problematic.

Results

Claimant referrals

The EEOC initially assigns each case a priority designation—high priority, medium priority, or low priority—on the basis of an intake interview (25). The mediation program is designed to focus on medium-priority cases, which initially appear to be neither groundless nor of sufficient potential to be selected for litigation by the EEOC. In general, complainants in medium-priority cases are asked whether they are willing to participate in mediation; if so, employers are asked to participate as well (3).

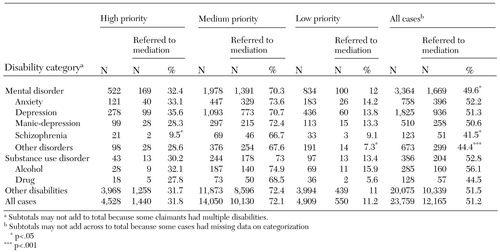

As Table 1 shows, 72.1 percent of medium-priority cases were referred to mediation, compared with 31.8 percent of high-priority cases and 11.2 percent of low-priority cases

Within each level of prioritization, approximately equal proportions of psychiatric, substance abuse, and other types of cases were referred to mediation. When cases were combined across prioritization levels, the claimants with psychiatric, non-substance use disorders had slightly but significantly lower mediation referral rates than cases involving other disorders (49.6 percent compared with 51.5 percent; χ2=4.41, df=1, p<.036). Only 9.5 percent of high-priority cases involving schizophrenia were referred for mediation, compared with 32.7 percent of other high-priority psychiatric cases (χ2=5.22, df=1, p<.022). The mediation referral rates for low-priority psychiatric cases involving "other" psychiatric or emotional impairments were significantly lower than those for all other low-priority psychiatric cases (7.3 percent compared with 13.6 percent; χ2=5.10, df=1, p<.024). Overall, the mediation referral rates for claimants who had schizophrenia were lower than the rates for claimants with all other psychiatric, non-substance use disorders (41.5 percent compared with 50.2 percent; χ2=4.72, df=1, p<.03).

Referral acceptances

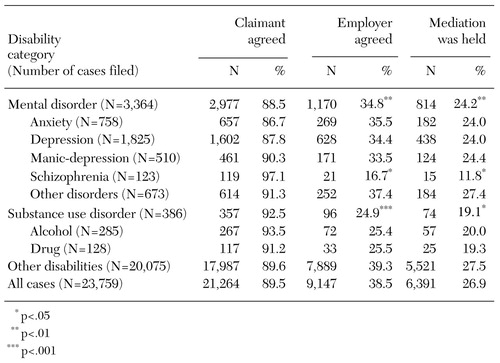

Table 2 shows that for all types of disability cases, only 38.9 percent of employers agreed to participate in mediation, compared with 89.5 percent of complainants. Consequently, only 26.9 percent of mediation referrals resulted in scheduled mediations.

We found no significant differences by type of disability in the proportion of complainants who agreed to accept mediation. However, employers were significantly less willing to participate in mediation when the complainant had a psychiatric disability rather than some other type of disability, excluding substance abuse (34.8 percent compared with 39.3 percent; χ2=9.00, df=1, p<.003). A similar but stronger pattern was found in employers' willingness to mediate in cases involving substance abuse (24.9 percent compared with 39.3 percent for persons with other types of disability; χ2=13.83, df=1, p<.001). Employers were least willing to participate in mediation involving complainants with schizophrenia (16.7 percent). Largely as a result of employers' being less willing to mediate when the complainant had a psychiatric disorder, a lower proportion of referred cases involving psychiatric impairments resulted in scheduled mediations (24.2 percent compared with 27.5 percent; χ2=7.41, df=1, p<.006). The same was true for cases involving substance abuse (19.1 percent compared with 27.5 percent; χ2=6.42, df= 1, p<.011).

Overall mediation outcomes

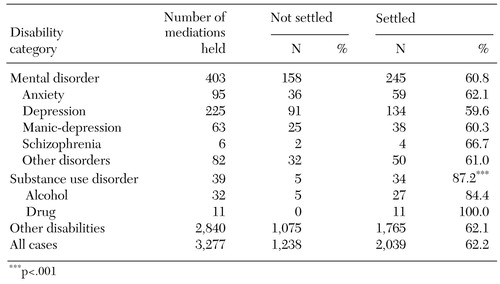

Mediated charges that do not result in settlement are termed "mediation failures" and are returned to the EEOC's regular pool of charges for investigation. Table 3 summarizes the outcomes of the mediations that were held. Between January 1, 1999, and June 30, 2000, a total of 3,277 Title I cases underwent mediation. Of these, 62.2 percent (N=2,039) were settled, and 37.8 percent (N=1,238) were not settled. Although the number of substance abuse cases was small (N=34), the rate of settlement was high (87.2 percent)—significantly higher than cases involving other disabilities (X2=10.45, df=1, p<.001). No significant differences in settlement rates were found among cases involving specific types of psychiatric impairment.

Benefits

The EEOC's charge data system tracks two types of monetary benefits. Employers provide "actual" monetary benefits through back pay, remedial relief, compensatory damages, or punitive damages. "Projected" monetary benefits are remedies to be provided by employers during a one-year period through hiring, promotion, reinstatements, or other such actions that would bring monetary returns. Complainants can also receive nonmonetary benefits, such as a reasonable accommodation, a positive job reference, or union membership.

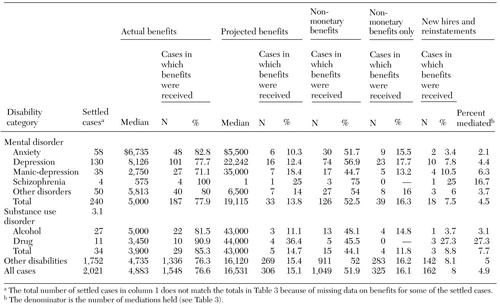

Table 4 shows the actual and projected monetary benefits as well as the nonmonetary benefits resulting from mediated settlements. Slightly more than three-quarters (77.9 percent) of the mediated settlements for persons with psychiatric, non-substance use disorders resulted in actual monetary benefits. When an employer agreed to mediate with complainants with psychiatric disabilities, both the median actual benefits and the projected monetary benefits these complainants received were slightly higher than those received by complainants with other disabilities (excluding substance use disorders). When an employer agreed to mediate with complainants with substance use disorders, the median actual monetary benefit received was lower than for complainants with other disabilities, even though the median projected monetary benefit was higher. As noted, however, very few employers were willing to mediate with individuals with substance abuse impairments.

Table 4 also shows that the amount of monetary benefits received by claimants varied by psychiatric disability. Among mediations resulting in actual monetary benefits for complainants with psychiatric disabilities, the median ranged from $575 for individuals with schizophrenia to $6,735 for individuals with anxiety disorders. Among mediations resulting in projected monetary benefits for complainants with psychiatric disabilities, the median ranged from $1 for one individual with schizophrenia to $35,000 for seven individuals with manic-depression.

The amount of actual monetary benefits received by claimants also varied by the type of substance use disorder. The median actual benefit was $3,450 for individuals with drug use disorders and $5,000 for individuals with alcohol disorders. In contrast, the median projected monetary benefits were similar for claimants with either type of substance use disorder—$44,000 for the four individuals with drug use disorders and $43,000 for the three individuals with alcohol disorders.

We also examined the number and percentage of mediations that resulted in new jobs and reinstatements. As Table 4 shows, 4.5 percent (N=18) of mediated cases involving complainants with psychiatric disabilities resulted in new jobs or reinstatements; this figure was 7.7 percent (N=3) for individuals with substance use disorders and 5 percent (N=142) for individuals with other impairments. The number of mediated settlements resulting in new hires or reinstatements was too small to determine whether the type of disability was significantly associated with this outcome.

As noted, settlements may also result in nonmonetary benefits for complainants. Among the mediated settlements for claimants with psychiatric disorders, 52.5 percent resulted in nonmonetary benefits, 16.3 percent resulted in only nonmonetary benefits, and 36.2 percent resulted in both monetary and nonmonetary benefits. The number of mediated settlements resulting in only nonmonetary benefits was too small to determine whether the type of disability was significantly associated with this outcome.

Discussion and conclusions

Previous studies and our own preliminary interviews at EEOC offices suggested that individuals with psychiatric disabilities might be excluded from mediation because of stereotypical assumptions about their inability to engage meaningfully in mediation. The data show that claimants with a psychiatric disability were less likely to be offered the opportunity to participate in mediation. Although this finding was statistically significant given the large sample the magnitude of the difference—about 2 percent—was not remarkable, being only about 4 percent lower than mediation offers for other ADA claimants. Individuals with schizophrenia were less likely to be referred to mediation than persons with other psychiatric or nonpsychiatric disabilities.

Employers were significantly less willing to mediate with people who had psychiatric or substance use disabilities than with people who had other disabilities. Because employers were less willing, the rate of mediations actually held for psychiatric and substance abuse cases was significantly lower. When mediations were held for claimants with psychiatric disorders, the rate of settlement was 60.8 percent. Thus any difference in the opportunity to participate in mediation would generate differences in benefit rates.

In other words, although the mediation program has helped increase the overall benefit rate for Title I cases, the gap in benefit rates between cases involving psychiatric disabilities and those involving nonpsychiatric, non-substance use disabilities has grown since mediation was fully implemented. In 1997-1998, the two-year period before the expansion of the EEOC's mediation program, the benefits gap between psychiatric cases and nonpsychiatric, non-substance abuse cases was about 2 percent (10.5 percent versus 8.6 percent). During the 18-month study period this gap doubled; the benefit rate of psychiatric cases rose half as quickly—to 12.7 percent—as the benefit rate for nonpsychiatric, non-substance abuse cases of 16.6 percent.

A somewhat surprising finding was that once employers agreed to participate in mediation with claimants with psychiatric disabilities, these claimants' chances of receiving a settlement were similar to those of other claimants. Furthermore, cases involving substance abuse were much more likely than either psychiatric cases or nonpsychiatric, non-substance abuse cases to be settled during mediation. Many commentators have noted that power imbalances between disputing parties in mediation can affect whether settlements are reached (9,13,14,15), and individuals with mental illness are unlikely to be in a position of power relative to their employers. Nevertheless, for most people with psychiatric disabilities who participate in mediation, this method of dispute resolution seems to offer at least as much help in obtaining a settlement as it does for those with other kinds of disabilities.

Differences were noted in direct monetary benefits paid to people with specific kinds of psychiatric disabilities and those with nonpsychiatric, non-substance use disabilities. Individuals with anxiety disorder or depression received considerably higher direct monetary benefits than individuals with nonpsychiatric, non-substance use disabilities. Those with schizophrenia or manic depression received substantially lower direct monetary benefits. Individuals with drug disorders also received substantially lower actual monetary benefits than other individuals.

It is also important to note that while the EEOC's mediation program was intended to target cases categorized as medium-priority (and these cases accounted for nearly 84 percent of all mediation referrals), many high-priority cases and some low-priority cases were referred to mediation. A major goal of the EEOC's mediation program has been to help parties resolve their workplace disputes informally; our findings suggest that the EEOC has gone a long way toward achieving that goal.

The findings of an EEOC-contracted assessment of its mediation program also were extremely positive (3). They show that individuals are generally satisfied with the program. Those findings, together with the findings presented here, indicate that the EEOC's mediation program has been a remarkably effective development and has the potential to provide meaningful case resolution services to thousands more EEOC claimants.

However, these positive results are tempered by research showing that employers view people with psychiatric disabilities with more distrust than people with other disabilities (27,28). Thus it is not surprising that employers seem to be less willing to mediate with people with psychiatric disabilities than with people with other types of disabilities. It is also not surprising that at least some EEOC investigators seem to share employers' feelings: EEOC employees are not exempt from the attitudes and misconceptions of the rest of society.

Clearly, however, an agency with the mission of the EEOC—to eradicate workplace discrimination based on race, gender, age, ethnicity, religion, and disability—needs to educate employers and its own employees about the capabilities of people with psychiatric disabilities. Many people with psychiatric disabilities experience work-related limitations associated with their disability; some, undoubtedly, file Title I charges that are frivolous. The evidence suggests, however, that most individuals with psychiatric disabilities who have employment discrimination complaints can participate meaningfully in mediation—especially if they have appropriate representation. Given a supportive work environment, many persons with psychiatric disabilities can be highly productive employees. Insofar as mediation may help foster such environments, it is a program that may benefit employers just as much as workers with psychiatric disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant RO1-MH-57077 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for its cooperation in providing data to the project's principal investigator, Kathryn Moss, Ph.D.

Dr. Moss is a research fellow at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Swanson is associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. Mr. Ullman is director of programs at the Institute for Human Services, Inc., in Honolulu, Hawaii. Mr. Burris is professor in the Beasley School of Law at Temple University in Philadelphia and associate director of the Center for Law and the Public's Health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Send correspondence to Dr. Moss, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 101 Conner Drive, CB 3386, Willowcrest Building, Suite 302, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-3386 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. High-, medium-, low-priority ADA disability cases filed with the EEOC between January 1, 1999, and June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000, that were referred to mediation, by type of disability

|

Table 2. Agreement to participate in mediation by charging party and employer in ADA disability cases filed with the EEOC between January 1, 1999, and June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000, and referred to mediation, by type of disability

|

Table 3. Outcomes of mediations held for ADA disability cases filed with the EEOC between January 1, 1999, and June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000, by type of disability

|

Table 4. Benefits awarded in mediations held for ADA disability cases filed with the EEOC between January 1, 1999, and June 30, 2000, and closed as of September 30, 2000, by type of disability

1. Mazade N, Blanch A, et al: Mediation as a new technique for resolving disputes in the mental health system. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 21:431-445, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Petrila J, Mazade N, Blanche A, et al: Mediation an alternative for dispute resolution in managed behavioral healthcare. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow, February 1997, pp 26-32Google Scholar

3. McDermott EP, Obar R, Jose A, et al: An evaluation of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Mediation Program, EEOC, 2000Google Scholar

4. Carnvale PJ, Pruitt DG: Negotiation and mediation. Annual Review of Psychology 43:531-582, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Woodward WJ: Evaluating bankruptcy mediation. Journal of Dispute Resolution 1:2-28, 1999Google Scholar

6. Duffy KG, Grosch JW, Olczak PW: Community Mediation: A Handbook for Practitioners and Researchers. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

7. Palenski JE: The use of mediation by police. Mediation Quarterly 5:31-38, 1984Google Scholar

8. Donohue JJ III, Siegelman P: The changing nature of employment discrimination litigation. Stanford Law Review 43:983-1033, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Emery RE, Wyer MM: Child custody mediation and litigation: an experimental evaluation of the experience of parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:179-186, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rubin S: Third party intervention in family conflict. Negotiation Journal 1:363-372, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Susskind L, Cruikshank J: Breaking the Impasse. New York, Basic Books, 1987Google Scholar

12. Edwards HT: Alternative dispute resolution: panacea or anathema? Harvard Law Review 99:668-684, 1986Google Scholar

13. Edwards HT: Where are we heading with mandatory arbitration of statutory claims of employment? Georgia State University Law Review 16:293-310, 1999Google Scholar

14. Fiss OM: Against settlement (based on speech at session of Civil Procedure and Alternative Dispute Resolution Sections of AALS, Jan 6, 1984) (transcript). Yale Law Journal 93:1073-1090, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Hughes S: Elizabeth's story: exploring power imbalances in divorce mediation. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 8:553-596, 1995Google Scholar

16. Moss K, Johnsen MC: Employment discrimination and the ADA: a study of the administrative complaint process. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:111-121, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Moss K, Johnsen M, Ullman M: Assessing employment discrimination charges filed by individuals with psychiatric disabilities under the Americans With Disabilities Act. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 9:81-105, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Moss K, Ullman M, Johnsen M, et al: Different paths to justice: the ADA, employment and administrative enforcement by the EEOC and FEPAs. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 17:29-46, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Moss K, Ullman M, Starrett B, et al: Outcomes of employment discrimination charges filed under the Americans With Disabilities Act. Psychiatric Services 50:1028-1035, 1999Link, Google Scholar

20. Moss K: The ADA employment discrimination charge process: how does it work and whom is it benefiting? in Employment, Disability, and the Americans With Disabilities Act: Issues in Law, Public Policy, and Research. Edited by Blanck PD. Evanston, Ill, Northwestern University Press, 2000Google Scholar

21. Moss K: Filing an ADA Employment Discrimination Charge: "Making It Work for You." Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2000Google Scholar

22. Moss K, Burris S, Ullman M, et al: Unfunded mandate: an empirical study of the implementation of the Americans With Disabilities Act by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Kansas Law Review 50:1-109, 2001Google Scholar

23. Moss K: Psychiatric Disabilities, Employment Discrimination Charges and the ADA. Silver Spring, Md, National Rehabilitation Information Center, 1996Google Scholar

24. Burris S, Moss K, Ullman M, et al: Disputing under the Americans With Disabilities Act: empirical answers, and some questions. Temple Political and Civil Rights Law Review 9:237-252, 2000Google Scholar

25. Ullman MD, Johnsen MC, Moss K, et al: The EEOC charge priority policy and claimants with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:644-649, 2001Link, Google Scholar

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

27. Baldwin ML: Can the ADA Achieve Its Employment Goals? in The Americans With Disabilities Act: Social Contract or Special Privilege ? Edited by Johnson WG. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 1997Google Scholar

28. Link B: Mental patient status, work, and income: an examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. American Sociological Review 47:202-215, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar