Receipt of Clinical Preventive Medical Services Among Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

A total of 267 patients who were receiving care for psychiatric and substance use disorders at a university medical center completed a self-report instrument assessing their previous receipt of clinical preventive services. High rates of mammography and Pap tests within the past year were observed (76 and 77 percent). Rates of immunization (hepatitis B and tetanus vaccines) varied from 11 percent to 78 percent. Rates of preventive counseling for sexual practices, diet, and avoidance of alcohol were lower than 25 percent in all groups. Only 6 percent of all patients reported having been screened for gun ownership, despite the high risk of suicide among gun owners.

Persons with psychiatric disorders engage in adverse health behaviors, such as cigarette smoking and HIV risk behaviors, at higher rates than the general population (1,2). Only 59 percent of low-income women over the age of 40 years who seek psychiatric care receive screening mammography (3). Given that suicide is the leading cause of death among persons who buy handguns in the first year after purchase, preventive assessment of firearm possession may be especially pertinent to psychiatric patients (4). Previous studies have suggested that psychiatric patients may not receive preventive services at recommended intervals (5,6). We surveyed patients who sought mental health services to determine the receipt of clinical preventive services among patients with mental disorders, patients' attitudes toward the receipt of clinical preventive services, and risk factors for failure to receive clinical preventive services.

Methods

Adult patients were recruited from May 1 through August 30, 1998, from three psychiatric service settings—inpatient units, outpatient clinics, and a chemical dependency unit—that were affiliated with a university hospital. All patients provided informed consent. A trained research assistant was available throughout the study period to help the patients complete the survey. Inpatients who were acutely psychotic, manic, severely depressed, catatonic, or intoxicated were approached after their acute symptoms remitted. Patients who were impaired by dementia or mental retardation were excluded from the study, because pilot testing showed that these patients were unable to complete the questionnaire.

The survey was designed to cover four areas: demographic information, including insurance status; access to medical care; previous receipt of clinical preventive services and counseling; and patients' attitudes toward the receipt of preventive services. Patient-perceived barriers to care were assessed with a checklist and one open-ended question. The checklist included items covering patient-based barriers, such as procrastination, lack of transportation, and fear of being treated rudely; financial burden, such as lack of insurance; and provider-related factors, such as the availability of office hours.

Psychiatric and medical diagnoses were determined by ascertaining the primary diagnosis at discharge for inpatients and the primary diagnostic code for outpatients. Recommendations for clinical preventive services were based on guidelines of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (7). The number of patients who were considered eligible for services varied by service. For example, the USPSTF recommends mammography for women aged 50 years and older, so only women in this age range were included in the analysis of receipt of mammography. For some services, such as dietary counseling, the entire sample was eligible for analysis.

Frequency analyses and descriptive statistics were used to assess the frequencies of responses in each service category. Bivariate analyses using the chi square test for categorical data were performed. Alpha was set at .05, and all p tests were two-tailed. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed for each key service to evaluate factors associated with failure to receive preventive services at recommended intervals. The following factors were modeled: age, gender, marital status, race, employment status, insurance status, diagnostic group, presence of a regular health care provider, time since last routine visit for medical care, and distance in miles from a medical provider. A separate regression was used for each independent preventive service.

Results

More women than men completed the survey (164 compared with 121). Of the 285 patients who completed the survey, 264 responded to all the general questions. The age range of the sample was wide (18 to 91 years). The mean±SD age was 38.6±14.3 years for women and 37.2±11.5 years for men. A total of 266 patients (94 percent) were non-Hispanic white, 128 (45 percent) were single, and 155 (56 percent) had an educational level of high school or less. A total of 251 patients (88 percent) had some form of medical insurance (private, federal, or state-funded).

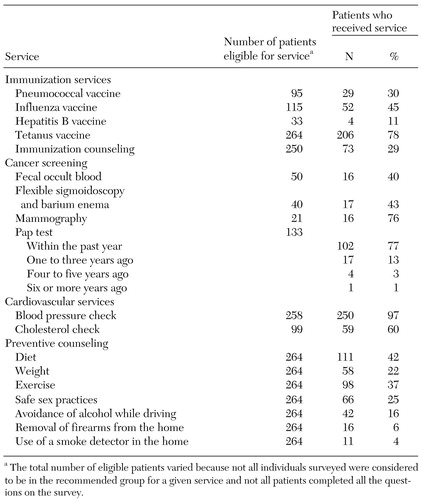

Receipt of clinical preventive services among the study participants is summarized in Table 1. The rate of receipt at recommended intervals varied according to the type of screening or service. Women reported high rates of gender-specific cancer screening services. Receipt of immunizations and colorectal cancer screening among the study participants was much lower. Only a quarter of all patients were advised about safe sexual practices (66 patients, or 25 percent), and even fewer were counseled about avoiding alcohol while driving (42 patients, or 16 percent) and removing firearms from the home (16 patients, or 6 percent). Although more than half the respondents were current smokers (159 patients, or 60 percent), only 80 patients (50 percent) reported that any doctor had advised them to stop smoking.

Generally, the most common risk factor for nonreceipt of a clinical preventive service was time since the last routine medical visit. Having a substance use disorder was a significant predictor of failure to receive a pneumococcal vaccination (odds ratio=9.0, SE=.70, p=.002). Patients with a personality disorder were also less likely to receive a pneumococcal vaccination, but the difference was not significant (p<.06). Women were less likely than men to receive a hepatitis B immunization, but this difference was also not significant (p<.06). Older age appeared to play little role in receipt of tetanus immunization, immunization counseling, or cholesterol screening.

In all diagnostic groups, a majority of the patients (74 percent to 93 percent) had received routine medical care for nonacute problems within the previous two years. However, only 63 percent of the substance abuse patients had received routine care during that period. More than half of all respondents (145 patients, or 55 percent) had sought emergency treatment for a medical problem one or more times in the past year.

Respondents rarely refused immunizations or cancer screening services (eight patients, or 3 percent). Most (186 patients, or 70 percent) thought that immunizations and cancer screening were "quite effective" to "very effective." The most common reason respondents gave for failure to receive recommended medical care was a "fear of being treated rudely or unkindly" by providers (93 patients, or 35 percent). Other reasons included procrastination (64 patients, or 24 percent), lack of insurance (64 patients, or 24 percent), expense (61 patients, or 23 percent), and the unavailability of care when it was needed (56 patients, or 21 percent).

Discussion and conclusions

The receipt of clinical preventive services among patients with psychiatric disorders is variable. Delivery depends primarily on the type of service, psychiatric diagnosis, and time since the patient was last seen by a primary care provider. Although the patients in this study reported that they considered clinical preventive services to be effective, they cited limitations to preventive medical care that were based on two primary themes: a fear of being treated rudely by the health care provider and lack of financial resources. Although a majority of the patients had received routine, nonemergency medical care in the previous two years, a substantial number had sought acute care and emergency care, which may indicate that their access to routine care was limited.

The results of this study highlight the importance of general health and safety screening, especially for firearm possession and smoking. Although 23 percent of all the study patients reported having a firearm in their home or car, only 6 percent of the patients reported that they had received counseling about removing the firearm. The proportion of patients who reported having a firearm in the home is at the upper end of the range of gun ownership reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (8). The implications for suicide prevention are substantial.

This study was limited by the fact that the data were self-reported. If patients overestimate their receipt of preventive services, the findings of this study may be overestimates as well. The sample was a convenience sample, which could have biased the results toward patients who were more interested in preventive care or those who were better able to complete the written questionnaire. However, our results on attitudes toward preventive services are consistent with those obtained among general medical outpatients.

The results of this study strongly suggest that psychiatrists cannot assume that their patients are receiving recommended preventive medical services. Future research and clinical efforts should be directed toward the education of psychiatrists in clinical practice to identify patients who are at risk of not receiving primary medical and preventive services and to the development of ongoing systems for monitoring the physical conditions of psychiatric patients (9,10).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant 9701032 from the Iowa Consortium of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge Michele Peterson and Heather Nichols for their assistance in subject recruitment and data management.

Dr. Carney is assistant professor of psychiatry and internal medicine at the University of Iowa College of Medicine in Iowa City. Mr. Allen is a doctoral candidate in the department of biostatistics of the University of Iowa College of Public Health. Dr. Doebbeling is professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa College of Medicine and the Iowa City Veterans Affairs Medical Center and professor of epidemiology at the University of Iowa College of Public Health. Send correspondence to Dr. Carney at 2-202 MEB, Department of Psychiatry, University of Iowa College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Receipt of clinical preventive services reported by 267 psychiatric and substance abuse patients

1. Black DW, Zimmerman M, Coryell WH: Cigarette smoking and psychiatric disorder in a community sample. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 11:129-136, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Velavka J, Convit A, Cozobor P, et al: HIV seroprevalence and risk behaviors in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Research 39:109-114, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Friedman LC, Moore A, Webb JA, et al: Breast cancer screening among ethnically diverse low-income women in a general hospital psychiatry clinic. General Hospital Psychiatry 21:374-381, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wintemute GJ, Parham CA, Beaumont JJ, et al: Mortality among recent purchasers of handguns. New England Journal of Medicine 341:1583-1589, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Carney CP, Yates WR, Goerdt C, et al: Psychiatrists' and internists' knowledge and attitudes about delivery of preventive medical services. Psychiatric Services 49:1594-1600, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Nazareth ID, King B: Controlled evaluation of management of schizophrenia in one general practice. Family Practice 9:171-172, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. United States Preventive Services Task Force: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2nd ed. Alexandria, Va, International Medical Publishing, 1996Google Scholar

8. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Online Prevalence Data, 1995-1998. Atlanta, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/brfss/index.aspGoogle Scholar

9. Sox HC Jr, Kiran LM, Sox CH, et al: A medical algorithm for detecting physical disease in psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1270-1276, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

10. McCarrick AK, Manderscheid RW, Bertolucci DE, et al: Chronic medical problems in the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:289-291, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar