Inpatient Psychotherapy Compared With Usual Care for Patients Who Have Schizophrenic Psychoses

Abstract

The study examined whether some patients with schizophrenia benefit from intensive inpatient psychodynamic psychotherapy while others are harmed by it. Multiple regression analyses were conducted with combined data from a follow-up study of 25 inpatients who were treated in a psychotherapeutic program and a follow-up study of 71 patients who received standard hospital treatment. The mean duration of the follow-up period was seven years. The analyses showed that improvement in global mental health status from the index admission to follow-up was associated with the type of treatment and with the patient's clinical condition at the index admission. A strong interaction effect was found between these two variables. Psychotherapeutic inpatient programs may be beneficial to patients who have higher levels of global functioning at the start of treatment but detrimental to other patients.

The place of psychodynamic psychotherapy in the treatment of psychotic disorders is controversial (1,2,3), possibly because some patients benefit from this treatment approach while others are harmed by it (4,5,6). To explore this question, we combined data sets from two follow-up studies of patients with schizophrenia. In one study, the patients were treated in a specialized psychotherapeutic ward (7). In the other, the patients received standard hospital treatment (8). All of the patients were treated in the same city during the same period, and follow-up interviews were conducted with identical research instruments. We sought to answer two questions. First, was outcome—global mental health status at follow-up—associated with the type of treatment program? Second, was there an interaction effect between type of treatment and global mental health status at the start of treatment?

Methods

Twenty-seven patients were treated in the inpatient psychotherapeutic program of Gaustad University Hospital in Norway between 1977 and 1987. Admission criteria to the ward were an ICD-8 diagnosis of schizophrenia, a duration of illness of more than three years, and an assessment by hospital staff of having received insufficient treatment. Each of the 27 patients received a second diagnosis at follow-up, on the basis of DSM-III-R criteria. The average duration of the follow-up period for these patients was seven years. One patient received a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and was excluded from the study, and one patient had committed suicide. Follow-up data were obtained for the remaining 25 patients.

The psychotherapeutic ward, established in 1977, was designed to treat young patients with schizophrenia. Patients were referred mainly from the same hospital and had had previous psychiatric hospitalizations. The staff had expertise in psychotherapy and milieu therapy with psychotic patients. All patients were offered nonstandardized, supervised individual psychotherapy in one to three weekly sessions. The milieu therapy was psychodynamically based, with emphasis on interpersonal relations and integration of family work. Patients used antipsychotic medications, but the use of medication as a crisis intervention was avoided. The ward was closed in September 2000.

Seventy-eight patients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia who were admitted to an acute care ward at Ullevaal University Hospital in Norway between 1980 and 1983 received standard hospital treatment and were followed up after seven years. All 78 were traced. Five had died, and two refused to participate in the study. Follow-up data were obtained for the remaining 71 patients. The study predated the establishment of regional ethical committees and so was approved by the data inspectorate and the ministry of social affairs.

All patients were interviewed at baseline and at follow-up by experienced psychiatrists using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (9) and a semistructured interview. The interviews were audiotaped. Global mental health status was measured with the Health-Sickness Rating Scale (HSRS) (10). Possible scores on the HSRS range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Kappa and intraclass correlations indicated that reliability was satisfactory.

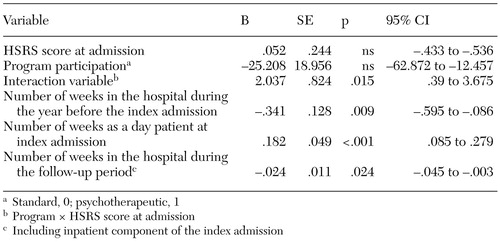

We conducted two multiple regression analyses, one using HSRS score at admission as the dependent variable and one using HSRS score at follow-up as the dependent variable. In the main multiple regression analysis of HSRS scores at follow-up, we introduced patient characteristics (age, sex, previous treatment, and HSRS score at admission), characteristics of the treatment program (duration of inpatient stay, number of days as a day patient, and antipsychotic dosage), and follow-up variables (duration of hospitalizations and time from the start of the index admission to follow-up).

Only variables that were significant in this analysis were entered into the final multiple regression analysis. To explore the relationship between functioning at the start of treatment and outcome, we introduced the interaction term "program × HSRS score at admission" at the last step of the final analysis. The effects were expressed as regression coefficients with standard errors and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs); t tests were used to compare HSRS scores at admission and follow-up. All tests were two-tailed. The level of significance was .05. Analyses were conducted with SPSS.

Results

The patients in the psychotherapeutic program had a slightly higher mean ±SD HSRS score than the standard hospital treatment group at admission (20.5±3.3 compared with 19.6±5.6) and at follow-up (34.6±21.3 compared with 32.5±10.6), although neither of these differences was significant.

Variables that were significantly associated with HSRS score at admission in the multiple regression analysis were participation in the psychotherapeutic program (B=4.686, SE=2.264, p=.041, CI=.186 to 9.185), age at index admission (B=-.136, SE=.064, p=.038, CI=-.264 to -.008), and duration of hospitalizations in the year before the index admission (B=-.114, SE=.052, p=.029, CI=-.216 to -.012).

In the final multiple regression analysis, we examined the relationship between type of treatment program and HSRS score at follow-up after controlling for other significant variables. Table 1 presents the results of this analysis. Apart from the interaction between HSRS score at admission and type of treatment program, only treatment-related variables—duration of hospitalizations in the year before the index admission, number of days as a day patient at the index admission, and total duration of hospitalizations in the follow-up period, including the index admission—had significant effects. For patients in the standard treatment group, HSRS score at admission had no significant effect on HSRS score at follow-up. However, patients in the psychotherapeutic program who had an HSRS score that was 10 points higher at admission had an improvement of approximately 20 points at follow-up.

Discussion and conclusions

We found a strong interaction effect between type of treatment and global mental health status at admission. The effect of the interaction variable was highly significant, even after we controlled for the type of program. Patients in the psychotherapeutic program had polarized outcomes—either very good or very bad—that were not seen among the patients who received standard hospital treatment. This finding indicates that an intensive psychotherapeutic program may be beneficial for patients with schizophrenia who have good functioning at admission but that it may have the opposite effect for patients with poor functioning at baseline. This supposition is consistent with the stress-vulnerability hypothesis and with the results of studies of personal therapy (5).

Our findings are based on two data sets that were analyzed retrospectively in a quasi-experimental design, and they should thus be interpreted with caution. The study design did not permit identification of more specific predictors of good outcomes for psychotherapeutic approaches. In future studies, better indexes of premorbid functioning (6) as well as neurocognitive tests and neuroimaging may help differentiate between groups of patients with different treatment requirements.

In most countries, psychiatric services have undergone several changes since this study was conducted. However, given the scarcity of evaluation studies of psychotherapeutic inpatient treatment for persons with schizophrenic disorders, our findings should be relevant to future service provision.

We hope that rather than discarding all forms of psychotherapy for psychotic patients, mental health professionals will make a renewed effort to tailor services to the specific capacities of individual patients and to increase the availability of these services for persons who will benefit from them.

Dr. Hauff, Dr. Melle, and Dr. Friis are affiliated with the department of psychiatric research and education of Ullevaal University Hospital in Oslo, Norway. Dr. Varvin is with the clinic of psychiatry at Aker University Hospital in Oslo. Dr. Laake is with the department of medical statistics and Dr. Vaglum is with the department of behavioral sciences in medicine at the University of Oslo. Send correspondence to Dr. Hauff, Department of Psychiatric Research and Education, Ullevaal University Hospital, 0407 Oslo, Norway (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results of final multiple regression analysis of scores on the Health-Sickness Rating Scale (HSRS) at follow-up among 25 patients in an inpatient psychotherapeutic program and 71 patients who received standard hospital treatment

1. Mueser KT, Berenbaum H: Psychodynamic treatment of schizophrenia: is there a future? Psychological Medicine 20:253-262, 1990Google Scholar

2. Fenton WW: Evolving perspectives on individual psychotherapy for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:47-72, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Gunderson JG, Frank AF, Katz HM, et al: Effects of psychotherapy in schizophrenia: II. comparative outcome of two forms of treatment. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:564-598, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. McGlashan TH, Keats CJ: Schizophrenia: Treatment Process and Outcome. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1989Google Scholar

5. Hogarty GE, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald D, et al: Three-year trials of personal psychotherapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: I. description of study effects and relapse rates. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1504-1513, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Hogarty GE, Greenwald D, Ulrich RF, et al: Three-year trials of personal psychotherapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: II. effects on adjustment of patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1514-1524, 1997Link, Google Scholar

7. Varvin S: A retrospective follow-up investigation of a group of schizophrenic patients treated in a psychotherapeutic unit: the Kastanjebakken study. Psychopathology 24:336-344, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Melle I, Friis F, Hauff E, et al: Patients with schizophrenia after the acute ward: seven years' service utilization and clinical course. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 54:47-54, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Spitzer RL, Williams J, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual: Third Revised Edition, Patient Version. New York, Biometrics Research Department, 1988Google Scholar

10. Luborsky L, Bacharach H: Factors influencing clinicians' judgments of mental health. Archives of General Psychiatry 31:292-299, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar