Factors Influencing Care Seeking for a Self-Defined Worst Panic Attack

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Only 60 percent of persons who experience panic attacks seek treatment for them, many at the emergency department. The author documented care-seeking behaviors among persons living in the community who had experienced panic attacks and studied determinants of care seeking. METHODS: In-depth structured interviews were conducted with 97 randomly selected community-dwelling adults who met DSM-III-R criteria for panic attacks. Participants were asked whether they had contemplated using or had actually used medical, alternative, and family sources of care when they had experienced their worst attack. RESULTS: Seventy-seven participants (79 percent) had considered using a general medical or mental health site when they experienced their worst attack. Of these, 50 (52 percent) had actually used such a site. General medical sites were contemplated more often (72 percent of participants) than mental health sites (27 percent), particularly emergency departments (43 percent) and family physicians' offices (34 percent). Other sources, such as friends or family members, alternative sites, and self-treatment, were contemplated less often. Once contemplated, certain sources were readily used, such as ambulances, family members, and self-treatment. Several factors were significantly associated with whether a person contemplated seeking care: access or barriers to treatment, perception of symptoms and of the reasons for the panic attack, and family-related variables. CONCLUSIONS: Contemplation and use of a mental health site after a panic attack was rare among the participants in this study. Further study of determinants of care seeking may help explain why persons who experience panic attacks fail to seek treatment or seek treatment from non-mental health sources.

Only 60 percent of persons who experience panic attacks seek medical care for them (1). Those who do seek care are most likely to visit a family physician's office, an emergency department, or a psychiatrist's office or to telephone for an ambulance (2). Persons who have panic attacks tend to be high users of medical care because they seek care for their panic symptoms; moreover, they do so regardless of their health insurance status or coverage (3). However, the decision-making processes of people who have panic attacks are not understood. If we could understand these processes, we might be able to increase the proportion of persons who seek appropriate care and thus reduce the inappropriate use of services, particularly emergency services.

Attempts have been made to identify predictors of service use among panic sufferers (1). These predictors, including demographic characteristics, panic characteristics, self-perceptions of symptoms and of reasons for the panic attack, and attitudes toward illness, vary by setting (2). However, previous studies of panic have been limited in that they examined predictors at nonspecified times during the course of the disorder and looked only at service use without looking at contemplation of care seeking.

According to the transtheoretical model of change, behavioral change moves through five stages: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance (4). During the precontemplation stage, the person does not even consider change. Change is considered during the contemplation stage. In the preparation stage, the person is actively preparing to make a change—for example, setting dates for the change. A person is considered to be in the maintenance stage when the change has been maintained for at least six months.

Although not previously applied to care-seeking behavior among panic sufferers, this model may provide a useful framework for considering patients' decision-making processes. In the context of decisions about care seeking, three stages emerge: precontemplation, contemplation or preparation, and action. An understanding of the determinants of these stages may enable us to promote the appropriate use of health care services by people who suffer from panic attacks.

The aim of this study was to explain care-seeking behavior among persons living in the community who had experienced panic attacks and to examine factors associated with whether and from what source a person sought care.

Methods

Sample

The panic attack care-seeking threshold study (1) was a community-based study conducted in San Antonio, Texas, between 1989 and 1992. Probability sampling methods similar to those of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study were used to survey households from 18 census tracts (5). The proportion of households that were asked to participate in the study in each census tract was varied to yield a sample that was demographically representative of the U.S. population in terms of age, sex, and race.

Beginning from a randomly selected street intersection in each census tract, clusters of three households were selected at intervals of eight households. The Kish method (6) was used to randomly select one adult (age 18 years or older) from each household. This person was screened for panic attacks with the panic disorder section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (7).

Persons who met DSM-III-R criteria for panic attacks were asked to participate in an in-depth interview. Participants were not required to meet criteria for full-blown panic disorder. Persons with panic attacks who agreed to participate provided information about whether and how they sought care for their worst panic attack and about what factors may have determined their care seeking. The survey instruments were translated into Spanish and back-translated, and the interviews were conducted in English or Spanish, according to participants' preferences. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of an occasional series on anxiety disorders edited by Kimberly A. Yonkers, M.D. Contributions are invited that address panic disorder, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Papers should focus on integrating new information that is clinically relevant and that has the potential to improve some aspect of diagnosis or treatment. For more information, please contact Dr. Yonkers at 142 Temple Street, Suite 301, New Haven, Connecticut 06510; 203-764-6621; [email protected].

Instruments

Potential determinants of whether and how people who experience a panic attack seek care include their symptoms and the reasons that they believe they are having the attack. Risk factors, such as panic characteristics, family characteristics, health attitudes and behaviors, comorbid psychiatric illness, coping strategies, work disability, and quality of life, are also critical determinants of whether and how people seek care. Need for care, which encompasses how people appraise and perceive their symptoms, are also critical determinants. Finally, access or barriers to health care are important factors in care seeking.

Panic characteristics included age at onset, duration of the disorder, and severity of the component symptoms of what participants thought of as their worst panic attack on the basis of the Acute Panic Inventory (8). Family characteristics included family size, the family's care-seeking behavior in the previous two months, family functioning as measured by the Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales (FACES-III) (9), life events as measured by the Family Inventory of Life Events (FILE) (10), and family support and stress as measured by the Duke Social Support and Stress Scale (DUSOCS) (11). The FACES-III has construct validity, an internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) of .62 to .77, and a test-retest reliability (r) of .80 to .83 (9). The FILE has an internal consistency of .81 and a test-retest reliability of .80 (10). The DUSOCS has construct validity and a test-retest reliability of .77 (11).

Health attitudes and behaviors were assessed with the Health Locus of Control (12), the Readiness for Sick Role Index (13), the Illness Attitude Scales (IAS) (14), and the Illness Behavior Questionnaire (IBQ) (15). The IAS has construct validity and a test-retest reliability of .69 to .96 (14). The IBQ has construct validity and a test-retest reliability of .67 to .87 (15).

Comorbid psychiatric conditions were assessed with the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) (16) and sections of the SCID that deal with major depressive episode, simple and social phobias, agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance abuse, and generalized anxiety disorder (7). The SCL-90 has been found to have validity and reliability; its test-retest reliability is .73 to .79. Coping strategies were assessed with the Ways of Coping Checklist (WCCL). Internal consistencies of the WCCL range from .76 to .88 (17). Finally, panic-related work disability and quality of life were assessed with instruments that have construct validity and internal consistencies of .60 to .74 (18).

Assessment of need for care included an open-ended question about the participant's thoughts at the time of the panic attack about what had caused the attack. Responses to this open-ended question were categorized as "going crazy," "stress or nerves," "minor physical problem," "serious physical problem," "dying," or "no explanation." Participants' appraisal of the panic attack was assessed with the Appraisal Dimension Scale (19). Their perception of 12 panic-related symptoms and 12 symptoms not associated with panic were assessed with five symptom-perception scales that addressed embarrassment, severity, threat to life, need for treatment, and disruption of functioning. These scales have construct validity and internal consistencies of .89 to .92 (20). Access and barriers to health care were evaluated with a checklist that included insurance coverage and personal actions necessary for obtaining care.

Sources of care examined among participants who sought care or contemplated seeking it were general medical sites—emergency departments, minor emergency rooms, medical clinics, ambulances, and physicians' offices—and mental health sites—mental health clinics and the offices of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and counselors. Care from alternative sources, such as telephone help lines, clergy members, chiropractors, and folk healers, was also assessed. In addition, participants were asked whether they had discussed their panic attacks with family members or friends and whether they had attempted self-treatment with over-the-counter medications, alcohol, or illicit drugs. For each source of treatment, participants were asked whether they had contemplated using the source for their worst panic attack and, if so, whether they had actually sought care through that source.

Analysis

To document stages of care seeking, sources of care were grouped into four categories: general medical sites, mental health sites, alternative sites, and self-treatment. In addition, determinants of care seeking from the most common sources—emergency departments, family physicians, ambulances, and family members—were assessed. For each of these sources, all potential determinants as assessed with the above-mentioned instruments were analyzed with bivariate testing (chi square and t tests). Potential determinants that yielded significant results (p≤.1) were retained for regression analysis. (This significance level was used because of the exploratory nature of the study and the relatively small sample.)

For this study, participants' stage of care seeking was determined by whether they considered seeking care for their worst attack and actually sought it. Persons in the precontemplation stage did not consider using a specific site or source. Those in the contemplation stage had considered using a source but did not actually use it. Participants in the action stage of care seeking used the source. The three categories are mutually exclusive. Participants who used the source were counted only in the action stage.

To identify independent determinants of each stage of care seeking, logistic regression was performed with the significant potential determinants as identified in the bivariate analysis. Logistic regressions that assessed the contemplation stage were based on the entire sample. Logistic regressions that assessed the action stage included only participants who had contemplated seeking care. The stepwise approach was used because of possible collinearity among potential determinants and because the sample was small. Determinants were considered significant if their beta coefficients loaded at a significance level of .05 or less.

Results

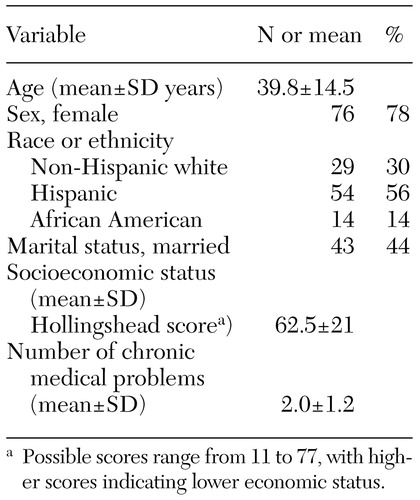

Of the 1,266 survey participants screened for panic attacks, 120 (9.4 percent) screened positive, and 97 of these had panic attacks and completed the in-depth interview. The characteristics of this sample are summarized in Table 1.

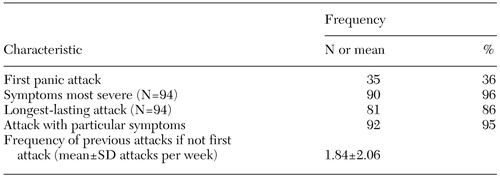

Because worst panic attacks were self-defined, participants were asked what symptoms or characteristics of their attack led them to consider it the worst attack. The responses to this question are summarized in Table 2. For the 62 participants whose worst panic attack was not also their first attack, the mean frequency of attacks before the worst attack was 1.84 attacks per week. Participants generally defined their worst attack as the attack that involved particular symptoms or the one during which the symptoms were the most severe.

If we consider self-treatment, family members, and the health care system or alternative sites as the possible sources of care, only 14 participants did not consider any action for their worst attack, and only 19 contemplated action without actually seeking care during their worst attack. Of the 57 participants who had ever sought care for their panic symptoms from a general medical or mental health site, 50 (88 percent) had done so for their worst attack. Of the 40 participants who had never sought care, 27 (68 percent) had contemplated seeking care for their worst attack.

Site-specific care seeking

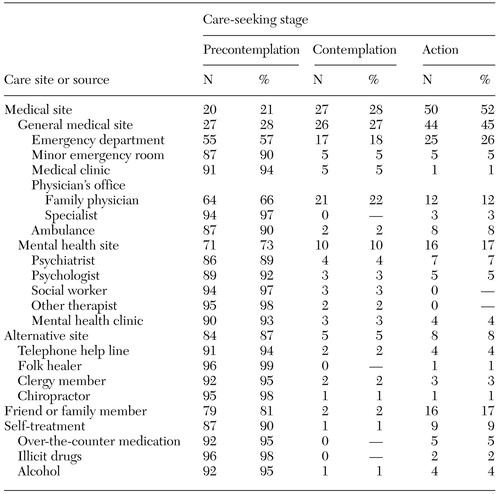

Table 3 presents the numbers of participants who contemplated using and actually used each source of care for their worst panic attack. Only 20 participants reported not having considered seeking care from a general medical site for their worst attack. Those who considered seeking medical care usually considered seeking it from a general medical site. Only 26 participants considered seeking care from a mental health site. Among participants who actually sought care, most used general medical sites. Only 16 participants sought care from a mental health site.

Most participants who considered using a general medical site considered either an emergency department or a family physician's office. Many medical sites were considered but not used. Thirteen participants considered using an alternative site. Eighteen participants considered seeking help from family members; of these, 16 actually did approach family members. Although self-treatment was rarely considered, it was generally used when it was considered.

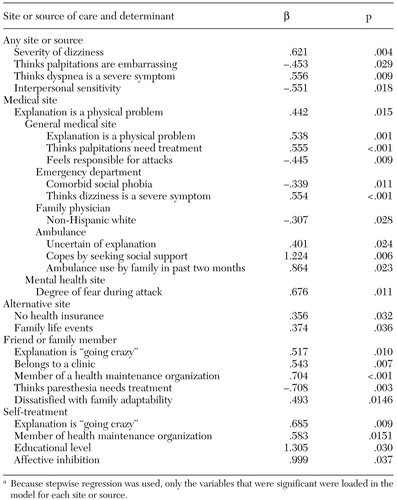

Determinants of care-seeking stages

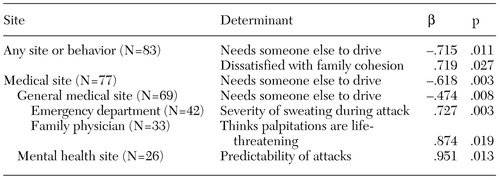

The determinants that were significantly associated with contemplation of treatment from various sources are presented in Table 4. Contemplation of seeking care from any source depended on the severity of symptoms and the person's perception of his or her symptoms and on whether the participant was embarrassed about palpitations. The determinants that were significantly associated with actual care seeking are presented in Table 5. Once a participant contemplated seeking care, action depended on whether the participant needed someone else to drive him or her to the care site and on the participant's level of satisfaction with family cohesion.

Contemplation of any medical site depended on whether the participant identified a physical cause of his or her attack, whereas actual use of any site depended on whether there was a barrier to care seeking—needing someone else to drive. These two determinants were also significantly associated with actually seeking care from a general medical site. Contemplation of a general medical site depended on the participant's perception of the symptoms of and reasons for the panic attack.

Actual use of emergency departments was associated with five symptoms of a worst attack and three barriers to access (data not shown), but only one aspect of symptom severity—sweating—was significant in the regression analysis. Although contemplation of ambulance use was associated with a person's perceptions of symptoms, attitudes toward illness, and demographic characteristics (data not shown), none of these variables were independent determinants.

Discussion

This study showed that whether someone who has a panic attack considers seeking care for it depends on the self-perceived severity of the attack, as also reported by Mechanic (21), and on the individual's embarrassment or sensitivity. Social embarrassment as a deterrent to care seeking has been described by Magee and colleagues (22). Once a person contemplates seeking treatment, support for care seeking—the availability of someone to provide transportation—is the critical factor.

Some sources of care for a worst attack were considered by fewer than 10 percent of participants—medical clinics, medical specialists, nonpsychiatric mental health sites, and specific alternative health care sites and self-treatment. Some sources were rarely considered (10 to 20 percent of participants) but were readily used if they were considered (at least 80 percent of participants). These sources included ambulances, any self-treatment, and friends or family members. The emergency department was the most considered and most used source of treatment for a worst panic attack. Although more participants contemplated visiting their family physician than visiting a mental health site, more participants actually used a mental health site.

Most participants considered seeking general medical or mental health care for their worst panic attack, and 65 percent of these actually presented themselves at such a site. Whether a person contemplated seeking treatment depended on the person's interpretation of the attack. Actual care seeking depended on whether the person needed someone else to drive him or her to the care site. Previous analyses of these data showed that reasons for seeking or not seeking care at any time depended on the panic sufferer's cognition and interpretation, whereas seeking any care depended on whether the person needed someone else to drive (1). However, this finding does not agree with those of other studies that suggest that care seeking depends on symptom severity (21), stress (23), comorbid psychiatric conditions (24), or race or ethnicity (25,26,27).

Care seeking at any time has also been found to depend on a person's experience with treatment, panic's interference with work (1), and whether the person meets DSM criteria for panic disorder (28). The results of this study suggest that although seeking care at any time and seeking care for a self-defined worst panic attack have similar determinants, whether a person seeks care for a specific attack may depend on a different set of predictors than those that determine whether a person ever seeks care for any panic attack or seeks care in general.

People who seek care for mental health conditions most often seek it from general medical sites (29). Severity of psychopathology and sociodemographic factors determine where mental health care is sought (30). Some other determinants of seeking care in a general medical setting were found among persons experiencing panic attacks: the person's interpreting the attack as a physical problem, needing someone else to drive, and believing that palpitations needed treatment and that he or she was not responsible for the attack. People may also use general medical sites rather than mental health sites to avoid the stigma associated with a psychiatric diagnosis.

The degree of fear during a panic attack was significantly associated with whether a person considered seeking care at a mental health site, and the predictability of panic attacks was associated with whether the person actually sought care from a particular source. Previous reports have stressed the importance of depressive symptoms (31), treatment experience, panic symptoms, perceptions of choking, and coping strategies in care-seeking behavior (2). The findings on the role of gender—which was not a predictor in this study—in mental health care-seeking behavior are contradictory (2,30,32,33).

Other determinants of contemplation of treatment at various general medical sites were whether the person interpreted the attack as a physical problem or had no specific explanation for it, whether the person's family had used an ambulance in the previous two months, whether the person coped by seeking social support, whether the person perceived dizziness as a severe symptom, and whether the person had social phobia that affected his or her contemplation of using an emergency department. Actual use of emergency departments depended on the severity of sweating. The results of previous studies suggest that important predictors of emergency room use are the presence and severity of symptoms, sociodemographic variables (2,26), the frequency of panic attacks (26), alcoholism, and a belief that fear needs treatment (2).

Study participants from minority ethnic groups were more likely to consider visiting a family physician, and those who thought palpitations were life-threatening were more likely to actually seek care from this source. The role of race or ethnicity in care seeking is unclear (26,34). Other sociodemographic variables may also be important (34). Previous reports have noted the importance of symptoms and appraisal of these symptoms (2,26).

In addition to contemplating seeking treatment from the health care system, the participants in this study considered seeking care from alternative sites. Lack of health insurance and family events were associated with contemplation of nontraditional sites. The results of previous studies suggest that phobic avoidance is an important factor in whether a person seeks care for panic from outside the health care system (2,22,35). However, in this study access variables, educational level, and psychological variables predicted contemplation of self-treatment or discussion with friends or family. Faravelli and associates (36) also found low self-medication rates among patients with panic disorder. Self-administration of alprazolam and alcohol have been associated with anticipation of benefit, anxiety symptoms, introversion or self-consciousness, and harm avoidance (37,38).

One of the implications of this study is that different factors affect different stages of care seeking. Contemplation of care seeking depends on mind-set. Attitudes toward illness, coping strategies, family-related variables, sociodemographic variables, access to care, and interpretation of the attack are important. Thus the question for a person experiencing a panic attack who is at the contemplation stage seems to be "Is this a treatable problem?"

This interpretation is compatible with Miller's assessment of issues important to people at the precontemplation stage (39). Whether participants needed someone else to provide transportation to the care site was associated with actual use of that site. At the action stage, the person's ability and need to act immediately is crucial. This interpretation can be supported by assessing variables that are common to both stages, such as symptom severity. The severity of fear was related to contemplation, while the severity of sweating was related to action. Similarly, perceptions of symptom severity and the need for treatment were associated with contemplation, while the threat to life was associated with action. These findings are consistent with Miller's assessment of issues that are important to persons who are in the contemplation stage (39).

Attempts to increase care seeking among persons who experience panic attacks should begin with an acknowledgment of the reality and importance of the experience so that panic sufferers can contemplate seeking care. Access barriers must then be dealt with so that care seeking can occur. Conveying these messages to people with panic disorder through the mass media, especially television, is a reasonable approach (40). Decreasing the use of emergency services—ambulances and emergency departments—may be amenable to intervention as well, through public education that provides an explanation for the symptoms and emphasizes that there is no need to seek emergency services.

This study had several limitations. First, care-seeking behavior was based on the participant's recall of an event that may have occurred years earlier. In addition, many of the Spanish translations of the instruments used in the study have not received adequate psychometric study. The sample was predominantly Hispanic and of lower socioeconomic status and thus may not have been representative of all community-dwelling persons who experience panic attacks. Although Eaton and colleagues (41) found no differences in care-seeking behavior by race or ethnicity, geography, or income, less educated persons reported more care seeking. Comparisons between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites have identified differences in predictors of care seeking between the two groups (42). Finally, multiple comparisons were used to develop these models, even though the sample was small. Although logistic regressions were performed to identify independent correlates, 16 regressions were used with 97 subjects to develop these models.

Conclusions

Persons experiencing what they recalled as their worst panic attack frequently contemplated using general medical sites but did not always use them. Mental health and alternative sites were rarely contemplated. Self-treatment was rarely contemplated but was used if it was contemplated. Access or barriers, perceptions of symptoms, and perceptions of reasons for the panic attack were important determinants of care-seeking stages. Longitudinal and qualitative research is needed to provide a better understanding of these determinants.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the Upjohn Company.

Dr. Katerndahl is affiliated with the department of family and community medicine of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, MSC-7795, San Antonio, Texas 78229-3900 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of 97 participants in the panic attack care-seeking threshold study

|

Table 2. Characteristics of a self-defined worst panic attack among 97 participants in the panic attack care-seeking threshold study

|

Table 3. Care-seeking behavior for a self-defined worst panic attack among 97 participants in the panic attack care-seeking threshold study

|

Table 4. Determinants of contemplation of care seeking among 97 participants in the panic attack care-seeking threshold studya

a Because stepwise regression was used, only the variables that were significant were loaded in the model for each site or source

|

Table 5. Determinants of care seeking among study participants who contemplated treatment for what they thought of as their worst panic attack

1. Realini JP, Katerndahl DA: Factors affecting the threshold for seeking care: the Panic Attack Care-Seeking Threshold (PACT) study. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 6:215-223, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

2. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Where do panic attack sufferers seek care? Journal of Family Practice 40:237-243, 1995Google Scholar

3. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Use of health care services by persons with panic symptoms. Psychiatric Services 48:1027-1032, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: Toward a comprehensive model of change, in Treating Addictive Behaviors. Edited by Miller WR, Heather N. New York, Plenum, 1986Google Scholar

5. Eaton WW, Holzer CE III, Von Korff M, et al: The design of the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys: the control and measurement of error. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:942-948, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kish L: A procedure for objective respondent selection within the household. Journal of the American Statistical Association 44:380-387, 1949Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R: Upjohn Version, Revised. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1989Google Scholar

8. Carr DB, Sheehan DV, Surman OS, et al: Neuroendocrine correlates of lactate-induced anxiety and their response to chronic alprazolam therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:483-494, 1986Link, Google Scholar

9. Olson DH, Portner J, Lavee Y: Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scales, 3rd ed. St Paul, University of Minnesota, 1985Google Scholar

10. McCubbin HI, Patterson JM, Wilson L: Family Inventory of Life Events and Changes. St Paul, University of Minnesota, 1980Google Scholar

11. Duke Social Support and Stress Scale. Durham, NC, Duke University, 1986Google Scholar

12. Wallston BS, Wallston KA, Kaplan GD, et al: Development and validation of the health locus of control (HLC) scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 44:580-585, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hibbard JH, Pope CR: Gender roles, illness orientation, and use of medical services. Social Science in Medicine 17:129-137, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kellner R: Illness Attitude Scales. Albuquerque, NM, University of New Mexico, department of psychiatry, 1983Google Scholar

15. Pilowsky I, Spence ND: Manual for the Illness Behavior Questionnaire. Adelaide, South Australia, University of Adelaide, department of psychiatry, 1981Google Scholar

16. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, et al: Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). Behavioral Science 19:1-15, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Vitaliano PP, Russo J, Carr JE, et al: Ways of Coping Checklist. Multivariate Behavioral Research 20:3-26, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Quality of life and panic-related work disability in subjects with infrequent panic and panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:153-158, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Vitaliano PP: Manual for Appraisal Dimension Scale and Revised Ways of Coping Checklist. Seattle, University of Washington, department of psychiatry, 1985Google Scholar

20. Jones RA, Wiese HJ, Moore RW, et al: On the perceived meaning of symptoms. Medical Care 19:710-717, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mechanic D: Illness behavior, in Medical Sociology, 2nd ed. Edited by Mechanic D. New York, Free Press, 1978Google Scholar

22. Magee WJ, Eaton WW, Wittchen HU, et al: Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:159-168, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Greenley JR, Mechanic D: Social selection in seeking help for psychological problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 17:249-262, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bucholz KK, Dinwiddie SH: Influence of nondepressive psychiatric symptoms on whether patients tell a doctor about depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:640-644, 1989Link, Google Scholar

25. Sussman L, Robins LN, Earls F: Treatment-seeking for depression by black and white Americans. Social Science in Medicine 24:187-196, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Katerndahl DA: Factors associated with persons with panic attacks seeking medical care. Family Medicine 22:462-466, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

27. Vernon SW, Roberts RE: Prevalence of treated and untreated psychiatric disorders in three ethnic groups. Social Science in Medicine 16:1575-1582, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Katon W, Vitaliano PP, Russo J, et al: Panic disorder: epidemiology in primary care. Journal of Family Practice 23:233-239, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

29. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, et al: Utilization of health and mental health services. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:971-978, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Durham ML: Predictors of outpatient mental health utilization by primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:908-913, 1994Link, Google Scholar

31. Cassano GB, Perugi G, Musetti L, et al: Nature of depression presenting concomitantly with panic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 30:473-482, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Briscoe ME: Sex differences in perception of illness and expressed life satisfaction. Psychological Medicine 8:339-345, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Dew MA, Dunn LO, Bromet EJ, et al: Factors affecting help-seeking during depression in a community sample. Journal of Affective Disorders 14:223-234, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Clancy CM, Franks P: Utilization of specialty and primary care. Journal of Family Practice 45:500-508, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

35. Wittchen HU, Reed V, Kessler RC: Relationship of agoraphobia and panic in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1017-1024, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Faravelli C, Degl'Innocenti BG, Giardinelli L: Epidemiology of anxiety disorder in Florence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:308-312, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Oswald LM, Roache JD, Rhoades HM: Predictors of individual differences in alprazolam self-medication. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 7:379-390, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, et al: Individual differences predictive of drinking to manage anxiety among non-problem drinkers with panic disorder. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 24:448-458, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Miller WR, Rollnick S: Motivational Interviewing. New York, Guilford, 1991Google Scholar

40. Kato T, Yamanaka G, Kaiya H: Efficacy of media in motivating patients with panic disorder to visit specialists. Psychiatry of Clinical Neuroscience 53:523-526, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, et al: Panic and panic disorder in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:413-420, 1994Link, Google Scholar

42. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Panic disorder in Hispanic patients. Family Medicine 30:210-214, 1998Medline, Google Scholar