Alcohol & Drug Abuse: Alcohol, the "Un-Drug"

Mr. B was recently paroled from state prison after serving his second term for crack cocaine possession. He had spent the last nine months of his sentence in an in-prison therapeutic community substance abuse treatment program. Three days after his release to parole, his friends gave him a welcome-home party, at which he consumed five or six beers. The beer triggered a desire for a "better high," and he quickly accepted an offer of crack cocaine. He was arrested on a possession charge two days later and is now serving his third sentence.

Mr. B's experience is typical of that of individuals who receive drug treatment in prison and are released to parole. Over the past 30 years, correctional rehabilitation efforts have increasingly targeted drug offenders rather than alcohol offenders. This shift has occurred partly because drug offenders now account for approximately a third of the nation's state prison population (1), but it has also been driven by a substantial body of literature that shows a drug-crime nexus. However, by emphasizing illicit drug use and diminishing the importance of alcohol use among offenders, we ignore a vast body of research on alcohol and crime, and we allow Mr. B's experience to become even more typical.

To be sure, illicit drug use is prevalent among offenders, regardless of whether they have been convicted of a drug-related crime. Data from the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring (ADAM) program indicate that 51 to 79 percent of adult male arrestees and 39 to 85 percent of adult female arrestees tested positive for at least one illicit substance in 2000 (2,3). Unfortunately, the ADAM program does not test for alcohol.

According to an analysis conducted by Columbia University's Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (4), approximately 80 percent of incarcerated offenders in the United States have current substance use problems. But despite the fact that a majority of these cases involve alcohol, criminal justice policy and practice remain focused on illicit drugs.

Our research and that of others reveals that for many offenders, heavy alcohol use is associated with significant increases in criminal behavior. According to an analysis conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (5), nearly twice as many convicted offenders were under the influence of alcohol as illicit drugs at the time of their offense.

The association between alcohol and violence has been reported by several sources. In our analysis of a national sample of substance abuse treatment clients, predatory offenders—as opposed to either victimless or nonspecialized offenders—were more likely to be dependent on alcohol alone than on cocaine, heroin, or other illicit substances (6). This finding is consistent with corrections-based research showing that a fifth of state prisoners convicted of violent crimes were under the influence of alcohol—and no other drug—at the time of their offense. By contrast, only 3 percent of violent offenders were solely under the influence of cocaine or crack, and only 1 percent were under the influence of heroin (4). Furthermore, the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that 65 percent of spousal violence occurs under the influence of alcohol, 11 percent under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and only 5 percent under the sole influence of illicit drugs.

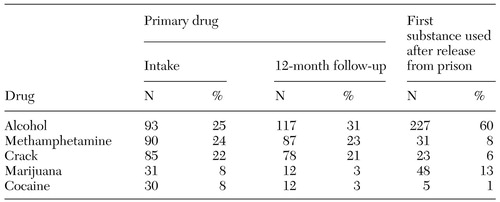

Even among offenders who report the use of multiple substances, alcohol tends to be the dominant drug of abuse. In a recent evaluation of a prison-based therapeutic community for substance-abusing offenders in California, we found that alcohol was the most commonly cited primary problem substance at intake and one year after release and was by far the most commonly reported substance to be used first on release from prison (Table 1). Anecdotal reports from clients indicate that a majority of the curriculum in therapeutic communities and other treatment programs is devoted to the cessation of illicit drug use, whereas reducing alcohol use is a secondary goal at best.

The trends shown in Table 1 suggest that alcohol's role in the larger constellation of substance use problems is central, not tangential, particularly in light of the growing body of literature associating alcohol with violence (7). Not only is alcohol use associated with violence and other crime, but it also hampers recovery from illicit substance use. One study of cocaine-dependent men in aftercare found that co-occurring alcohol use significantly predicted whether a patient relapsed to cocaine use or had a "near miss" (8).

Although the term "substance abuse" was adopted to encompass problematic use of either illicit drugs or alcohol, criminal justice policies reveal a clear emphasis on the former. In fairness, it is easy to see how this distinction has evolved. The primary goal of incarceration is to punish and incapacitate individuals for committing criminal offenses (9). Hence the use—and even abuse—of a licit substance should arguably be given lower priority than the use of illicit ones. But if correctional supervision in prison and on parole is also intended to prevent subsequent offenses, this perspective will have to change.

Although most users of alcohol do not engage in violence or other types of criminal behavior, persons who become involved with the criminal justice system typically have extensive criminal histories, and their use of alcohol is associated with an increased risk of subsequent use of illicit drugs and criminal behavior—especially violence. Despite these negative associations, alcohol receives little specific attention in corrections-based substance abuse programs compared with cocaine, crack, heroin, and—more recently—methamphetamine. In addition, parole departments do not treat alcohol as seriously as illicit drugs.

On the basis of our research findings and the broader body of literature on alcohol and crime, we offer the following recommendations.

Enhance the emphasis on alcohol use. The ongoing perception that alcohol is the benign constituent of a larger set of "substances" is at odds with the research literature. Given the prevalence of alcohol use and its well-documented association with violence and other crime, drug treatment programs that tangentially address alcohol use would be more justified in doing the converse—that is, placing equal or greater emphasis on treating alcohol use than use of other substances. The true goal, of course, should be to assist offenders in the cessation of any substance that interferes with self-control.

Increase the availability of Alcoholics Anonymous in prison settings. By virtue of their anonymous philosophy, few Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) programs have subjected themselves to rigorous evaluations, making empirical support for these programs scarce. However, in the course of our evaluations of other correctional programs, we found that concurrent AA participation commonly distinguishes successful parolees from unsuccessful ones. Another important advantage of AA is that it is a self-supported organization led by volunteers. This quality is particularly important in prison settings, where budgetary constraints are the most commonly cited reason for not providing substance abuse treatment (4).

Require abstinence from alcohol as a condition of parole. Most parolees, unless they have been convicted of an alcohol-specific crime—for example, driving under the influence—are simply admonished not to use alcohol "in excess." Such a vague mandate is unlikely to curb consumption. However, because a parolee is technically in custody until discharged from parole, he or she should be required to abstain from alcohol use during this period. The most common argument against this approach is that alcohol is legal. However, in other contexts, clear precedents have been established in which parole conditions can exceed requirements made of the general population. For example, most parolees are not allowed to fraternize with other felons but can do so when they are no longer under parole supervision.

Our two main premises—that alcohol use is prevalent among offenders and that facilitating reductions in alcohol use among these persons would reduce their levels of re-offending—are difficult to dispute. However, there is reluctance to apply these observations to criminal justice policy. Consequently, our first two recommendations are modest, and in most correctional systems could be accomplished with minimal resistance. Our third recommendation—requiring abstinence from alcohol as a condition of parole—would require more frequent random breath testing and the establishment of graduated sanctions for positive tests. Still, in light of the prominent role that alcohol plays in facilitating violent crimes and precipitating relapse to other forms of drug use, such an ambitious undertaking could significantly improve parole outcomes and public safety.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this paper was supported by the California Department of Corrections, contract 97.243.

The authors are affiliated with the integrated substance abuse programs of the Neuropsychiatric Institute and Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles, 11050 Santa Monica Boulevard, Suite 150, Los Angeles, California 90025 (e-mail, [email protected]). Sally L. Satel, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Self-reported primary drug used and first substance used after release from a prison-based substance abuse program (N=379)

1. Bureau of Justice Statistics: Correctional Populations in the United States, 1996. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 1999Google Scholar

2. National Institute of Justice:2000 Annualized Site Reports from ADAM. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2000Google Scholar

3. National Institute of Justice: ADAM Preliminary 2000 Findings on Drug Use and Drug Markets. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, 2001Google Scholar

4. Behind Bars: Substance Abuse and America's Prison Population. New York, Columbia University, Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1998Google Scholar

5. Alcohol and Crime. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1998Google Scholar

6. Farabee D, Joshi V, Anglin MD: Addiction careers and criminal specialization. Crime and Delinquency 47:196-220, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Parker RN, Auerhahn K: Alcohol, drugs, and violence. Annual Review of Sociology 24:291-311, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

8. McKay JR, Alterman AI, Rutherford MJ, et al: The relationship of alcohol use to cocaine relapse in cocaine-dependent patients in an aftercare study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:176-180, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Logan CH, Gaes GG: Meta-analysis and the rehabilitation of punishment. Justice Quarterly 10(2):245-263, 1993Google Scholar