Datapoints: Psychiatric Outpatient Care in Germany and the United States

Many mental health advocates and practitioners in the United States look enviously at the health care systems of other countries. The American Psychiatric Association's "wish list" for health care reform (1) includes universal coverage, unconstrained access to specialists in a fee-for-service setting, and generous mental health benefits such as psychotherapy without copayments. Germany's health care system meets these criteria.

We compared 1997-1998 data on outpatient mental health care provided by physicians in Germany and the United States. We focused on data for patients with a primary diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder—ICD-9 codes 291-293, 295-298, and 300-314. The German data is proprietary and based on claims from sickness funds, and the U.S. data come from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey.

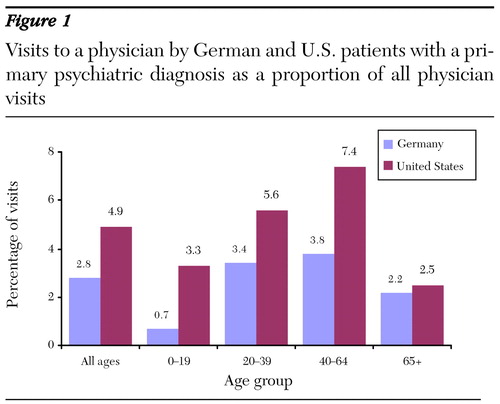

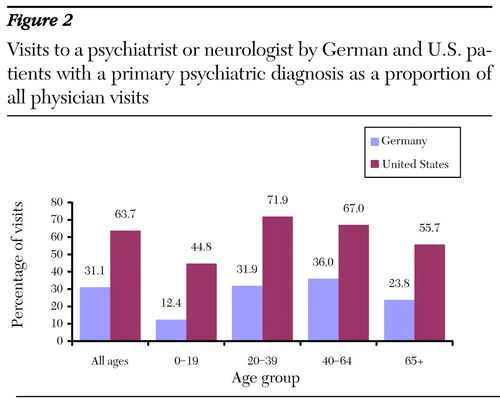

Among all outpatient visits to a physician, the proportion by patients with a psychiatric disorder was much higher in the United States (Figure 1). Furthermore, U.S. patients with a psychiatric disorder were much more likely to visit a psychiatrist or a neurologist than their German counterparts (Figure 2). Thus it appears that the provision of comprehensive mental health insurance coverage and open access to specialists does not ensure a greater role for psychiatrists. Instead, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis in Germany relied more heavily on primary care physicians than did U.S. patients, where tightly managed care is the norm.

In the seemingly ideal German system, what factors might lead to a less prominent role for psychiatrists? Cultural differences and differences in the prevalence and severity of mental disorders may be contributing factors. However, numerous less visible institutional factors play an important role, including centralized decisions about physician training and practice location, an emphasis on primary care, audits of providers with unusual treatment patterns, and global budgets for pharmacy. These less visible institutional factors have kept the seemingly unconstrained German system viable.

Even though some American psychiatrists in the much maligned U.S. system may admire the German system, it is not clear that they would fare any better in Germany. More important, it is not clear which system provides better outcomes for patients.

Dr. Häussler and Dr. Rehberg are affiliated with the Institute for Health and Social Research, Wichmannstrasse 24, D-10787 Berlin, Germany (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Sturm and Ms. Bao are affiliated with Rand in Santa Monica, California. Harold A. Pincus, M.D., and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Visits to a physician by German and U.S. patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis as a proportion of all physician visits

Figure 2. Visits to a psychiatrist or neurologist by German and U.S. patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis as a proportion of all physician visits

1. American Psychiatric Association: APA's 12 Principles of National Health Care Reform. Available at http://www.psych.org/libr_publ/reform.cfm, accessed March 7, 2001Google Scholar