The Relationship of Restrictions on State Hospitalization and Suicides Among Emergency Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study explored the relationship between mandated decreases in transfers to a state hospital from a large urban psychiatric emergency facility and the occurrence of suicide in the catchment area served. METHODS: During 1996, new admission criteria that emphasized psychiatric diagnosis and potential benefit from hospitalization and that restricted the admission of recidivistic patients and of those with a primary diagnosis of a substance use disorder were phased in. Data on the number of patients seen in a psychiatric emergency service and the number transferred to the state hospital were obtained for the period 1994-1998. Data on all completed suicides in the county served by the hospital were also obtained. RESULTS: During 1994 and 1995, a total of 9,308 patients were transferred to the state hospital. In 1997 and 1998, a total of 4,072 patients were transferred. The number of patients seen in the emergency service remained constant throughout the study period. No change was noted in the absolute number or the rate of suicide in the county after the new admission criteria were implemented. A total of 164 suicides were recorded in 1994-1995 (12 per 100,000 population per year), compared with 152 in 1997-1998 (ten per 100,000 population per year). CONCLUSIONS: Transfers to the state hospital were reduced by 56 percent, with no change in the suicide rate. This finding suggests that the availability of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization may not have a direct effect on the suicide rate.

The past decade witnessed significant changes in the delivery of health care in the United States. Managed care and other cost containment regimens have dramatically altered the practice of medicine and of psychiatry. Cost containment has become a dominant feature of clinical decision making, and it is often imposed by nonmedical entities. These same forces have moved from the private into the public sector, resulting in dramatic changes in the practice of psychiatry in the public mental health system. Central to this change has been a forced reduction in the use of inpatient care and a decrease in length of inpatient stay.

In response to budgetary constraints, the psychiatric emergency service at Grady Memorial Hospital was directed to admit fewer patients to the state hospital. This service is the emergency receiving facility for Fulton County, Georgia. The county contains virtually the entire city of Atlanta and has a population of more than 700,000 residents; the county has been growing at a rate of 2 percent per year throughout the past decade. The ethnic composition of Fulton County is 49 percent African American, 48 percent white, and 3 percent other races.

Involuntary patients arrive from a variety of agencies, including the police department, the sheriff's department (when it is executing probate commitments), and other mental health providers, such as the mobile crisis team, community mental health centers, and other hospitals. Most patients who require inpatient psychiatric treatment are transferred to the Georgia Regional Hospital at Atlanta, the state hospital that serves Fulton County.

The mandate to decrease admissions was formalized in 1995, and new admission priorities were phased in during 1996. This change in hospitalization practices provided a naturalistic laboratory in which to study the consequences of large-scale changes in mental health policy on treatment outcomes.

Suicide is the ultimate adverse outcome in psychiatry. Patients seeking care at psychiatric emergency facilities are at particularly high risk of suicide (1,2). The goal of this study was to determine whether large-scale changes in the manner in which these patients were treated had an impact on the suicide rate in the catchment area.

Methods

In response to the directive to admit fewer patients to the state hospital, new admission criteria were formulated to stratify patients into high- and low-priority groups. Patients for whom admission is considered a high priority are those with new-onset psychiatric disorders, significant diagnostic uncertainty, medical complexity, or known chronic mental illness accompanied by acute decompensation. The high-priority group includes mostly patients with severe unipolar depression, those with bipolar disorder who are in a manic or severely depressed state, and those with schizophrenia, especially patients in a first psychotic episode. The potential for violence and the presence of symptoms known to contribute to acute suicide risk are considered when patients are prioritized for admission.

Patients for whom admission is a low priority are those with primary substance use disorders, including substance-induced mood and psychotic disorders; dually diagnosed patients whose presenting symptoms are due to substance use; and patients who are recidivistic and poorly compliant with treatment. Patients with personality disorders, chronic suicidal ideation, or long-standing patterns of self-injurious behavior are also in the low-priority group. Even before the change in admission practices, admission was considered a low priority for the self-injurious group, and these patients were typically treated acutely in the outpatient observation area before being discharged. It should also be noted that "social admissions," whereby homeless patients gain admission by expressing suicidal ideation, were not permitted.

Data were extracted from the psychiatry emergency service's daily and monthly activity logs from 1994 through 1998. These records document the numbers of patients seen and the patients' ultimate disposition. A database of completed suicides in Fulton County from 1994 through 1998 was obtained from the office of the medical examiner. The database contains extensive information on all declared suicides, including method and toxicology, and includes all suicides discovered in Fulton County, regardless of the victim's county of origin. Additional information on suicides, traffic fatalities, accidental deaths, and homicides was obtained from the Web site maintained by the Fulton County medical examiner (3). Demographic data for Fulton County was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau Web site (4).

Statistical analyses were performed by using StatView v5 for Macintosh computers. Chi square tests were used for nonparametric comparisons, and comparisons of continuous data were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni/Dunn post hoc analysis, as implemented by the StatView algorithms.

All data collection and study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Emory University School of Medicine.

Results

During 1994 and 1995, a total of 32,677 patients were seen in the psychiatry emergency service (mean± SD=1,362±287 per month). A total of 9,308 were hospitalized (mean±SD= 388±42 per month). In this interval, 28.5 percent of psychiatric emergency service patients were admitted to the state hospital. In 1997 and 1998, a total of 28,986 patients were evaluated in the emergency service (mean±SD=1,208±130 per month), resulting in 4,072 admissions (mean± SD=170±26 per month), for a state hospital admission rate of 14 percent. Thus the number of transfers to the state hospital was reduced by 56 percent between 1994 and 1998.

No significant difference was found in the average number of patients evaluated per month in the psychiatric emergency service for any year between 1994 and 1998, but a significant drop was noted between 1994 and 1998 in the average number of patients per month who were admitted to the state hospital (F=92.60, df=4, 55, p<.001).

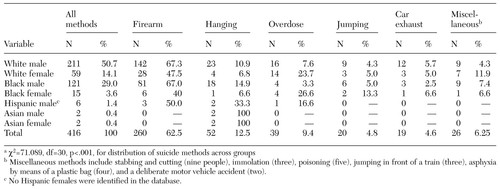

As shown in Table 1, there were 416 suicides in Fulton County between 1994 and 1998. The demographic characteristics of the individuals who committed suicide did not change across the study interval, nor was there any change in the frequencies of the common methods. Between 1994 and 1998, 28.8 percent of the suicide victims (N=118) had a positive test for alcohol, and the yearly rates did not vary appreciably. During this interval, 9.9 percent of suicide victims (N=44) had a positive test for cocaine, and no significant year-to-year differences were noted.

Between 1988 and 1998 in Fulton County, the mean±SD number of suicides per year was 86.7±10.14, with a high of 105 in 1992 and a low of 73 in 1998. A total of 164 suicides occurred in Fulton County during 1994 and 1995, compared with 152 suicides in 1997 and 1998. The mean number of suicides per month (6.93±2.25) did not vary significantly across the entire interval. No statistically significant variation was noted in the monthly rate of suicides per 100,000 population between 1994 and 1998—12 per 100,000 population per year in 1994-1995 and ten per 100,000 population per year in 1997-1998.

Discussion

The psychiatric emergency service at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta formulated new admission criteria that emphasize psychiatric diagnosis and potential benefit from hospitalization. As a result, transfers to the state hospital were reduced by 56 percent, and the rate of admissions was cut in half, from 28.5 percent of all psychiatric emergency service patients to 14 percent.

Patients who are considered to have a low priority for admission are those with primary or comorbid substance use disorders, long-standing personality disorders, and chronic recidivism and noncompliance with treatment. Although a large proportion of these patients express suicidal ideation during their evaluation, the reduction in transfers to the state hospital did not result in a change in the number or rate of suicides in the catchment area served by the emergency service. In addition, the number of suicide victims who tested positive for alcohol or cocaine did not change over the study period, which suggests that inpatient psychiatric treatment does not have an appreciable impact on the rate of suicide in the group of patients for whom admission is considered a low priority.

Suicidal ideation and behavior is one of the most common presenting complaints of patients seeking treatment at psychiatric emergency facilities, and these patients are at a considerable risk of subsequent suicide (1,2). Patients in the low-priority group would be expected to be at increased risk of suicide given the preponderance of substance use disorders and poor social support in this group. Substance use disorders have been consistently recognized as chronic risk factors for suicide (5,6,7,8). When a patient with a personality disorder is in crisis, the long-standing practice has been to allow the patient to deescalate in a safe environment and to discharge the patient within 24 hours. This practice was followed in the psychiatric emergency service before the changes instituted in 1996.

This study focused only on cases of suicide declared by the coroner in the county served by the emergency service. High-risk patients may have committed suicide in another county, which may account for the unchanged suicide rate in Fulton County. However, this explanation is unlikely given the general tendency of psychiatric patients to migrate into central urban areas closer to treatment facilities (9). Grady Hospital is in downtown Atlanta and is the single largest provider of medical and mental health services in Fulton County, in the region, and in the state of Georgia. The Grady psychiatric emergency service conducts 80 to 90 percent of all psychiatric evaluations in the public mental health system in Fulton County. Typically patients seen in other settings—such as community mental health centers, other hospital emergency services, mobile crisis units, and the Fulton County Alcohol and Drug Treatment Facility—who are believed to be at risk of suicide are transferred to the Grady emergency service for further evaluation and disposition.

Another possible explanation for the lack of change in the number of suicides is that the coroner misclassified some cases of suicide. However, this explanation is unlikely, because the numbers and rates of traffic fatalities and accidental deaths remained constant throughout the study period. No change was observed in the rates of suicide by different methods during the study period—from the common methods, such as gunshot, hanging, and overdose, to rare methods that could be mistaken for accidents, such as motor vehicle accidents, fires, and being struck by a train.

Another limitation of this study is that suicide attempts were not documented, and other clinical outcome data, such as follow-up clinic visits, reduction in symptoms, and changes in daily functioning and quality of life, were not captured. We are in the process of analyzing some outcome variables, including serious suicide attempts, 911 calls by persons with suicidal ideation, and treatment compliance.

A significant factor that must be considered when evaluating these results is that the psychiatric emergency service at Grady Hospital is a dedicated facility that has staff and physicians whose sole responsibility is to work in the emergency service. The ability to hold, observe, and treat patients for up to 24 hours before disposition allows for a careful assessment of suicide risk over a period of extended evaluation, which has been shown to affect rates of hospitalization (10). A physician evaluates all patients, and the staff has extensive experience in conducting emergency psychiatric assessments and crisis intervention.

The new admission priorities did not result from an arbitrary decision to include certain diagnoses and exclude others but emerged from extensive discussions among the senior staff and from consideration of published data (11,12,13,14,15). Because a resource allocation decision had to be made, high- and low-priority groups were established. Patients in the low-priority group have significant psychiatric needs. A comprehensive analysis of ICD-9 diagnostic codes for patients seen in the service from December 1999 through 2000 (a similar database is not available for the 1994 through 1998 interval) showed that 35 percent of the patients had a primary substance use disorder. Patients with cluster B personality disorders accounted for a very small percentage (1.1 percent) of the patients seen. Patients with schizophrenia were the largest single diagnostic group (25 percent).

Assuming that the mix of patients has not changed appreciably since the study period (1994-1998), it seems likely that many patients in the low-priority group had an axis I diagnosis and a comorbid substance use disorder. In many ways, patients in this group are at high risk of suicide; they have poor social support, substance use disorders, impulsivity, poor treatment compliance, and limited access to services.

The relationship of psychiatric hospitalization to the prevention of suicide remains obscure. Data from this study suggest that the availability of inpatient psychiatric services does not have an impact on the occurrence of suicide. This finding is consistent with other reports. A study of 191 district health authorities in Great Britain found that the availability of mental health workers and mental health resources was not correlated with the suicide rate, whereas socioeconomic factors such as income, unemployment, and being from a single-person household were (16). A related study in Great Britain compared two approaches to lowering the national suicide rate: interventions targeted at high-risk groups and population-based strategies (17). The high-risk interventions showed only a modest preventive effect, and population-based interventions were believed to have a much greater potential benefit. The population-based strategies included improving socioeconomic conditions, reducing unemployment, and minimizing the availability of high-lethality suicide methods. Because the leading method of suicide in the United States and in Fulton County is self-inflicted gunshot, one population-based strategy would be to limit the availability of firearms.

A comprehensive analysis of suicides in Great Britain from 1996 to 1998 found that 16 percent of the suicides occurred on inpatient psychiatric wards and an additional 24 percent occurred within three months of discharge, with the highest rate in the first week after discharge (18). In a ten-year follow-up of 150 patients who had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital after a suicide attempt, 25 percent made a second attempt and 12 percent died by suicide; the highest risk occurred in the two years after the index admission (19). A study of 1,397 suicide victims found that 56 percent were successful on the first attempt (20). A similar study of 10,040 victims found that only 24 percent received mental health services in the year before the fatal act (18). These data suggest that a subgroup of patients at very high lifetime risk of suicide are admitted to psychiatric hospitals but that hospitalization may not be particularly effective in preventing this outcome.

Preventing suicide continues to be one of the truly vexing problems in the practice of psychiatry. Even though extensive research has examined the epidemiology, psychology, and biology of suicide, the national rate of more than 30,000 victims a year has remained the same for decades. Increasing the availability of effective treatments, raising public awareness of psychiatric disorders and treatments, and lessening the stigma of mental illness hold out the most hope for having a long-term, widespread impact on the epidemic of suicide (21).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Randy Hanzlick, M.D., and Dennis McGowan for their assistance in this project. This work was supported in part by grant K23-RR15531-01 from the national Center for Research resources, grant RO1-MH60745-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and two awards to Dr. Garlow, a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression and a pilot project award from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University School of Medicine and the psychiatric emergency service at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Send correspondence to Dr. Garlow, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Emory University School of Medicine, 1639 Pierce Drive, Suite 4000, Atlanta, Georgia 30322 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Distribution of suicides by race, gender, and method in Fulton County, Georgia, 1994 through 1998a

a χ2=71.089, df=30, p<.001, for distribution of suicide methods across groups

1. Hillard JR, Ramm D, Zung WW, et al: Suicide in a psychiatric emergency room population. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:459-462, 1983Link, Google Scholar

2. Dhossche DM: Suicidal behavior in psychiatric emergency room patients. Southern Medical Journal 93:310-314, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Fulton County medical examiner. Available at http://www.fcmeo.org/stats.htmGoogle Scholar

4. US Census Bureau. Available at http://venus.census.govGoogle Scholar

5. Pages KP, Russo JE, Roy-Byrne PP, et al: Determinants of suicidal ideation: the role of substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:510-515, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Fowler RC, Rich CL, Young D: San Diego Suicide Study: II. substance abuse in young cases. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:962-965, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al: Prevalence of cocaine use among residents of New York City who committed suicide during a one year period. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:371-375, 1992Link, Google Scholar

8. Ward NG, Schuckit MA: Factors associated with suicidal behavior in polydrug abusers. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 41:379-385, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

9. Breslow RE, Klinger BI, Erickson BJ: County drift: a type of geographic mobility of chronic psychiatric patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 20:44-47, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gillig PM, Hillard JR, Bell J, et al: The psychiatric emergency service holding area: effect on utilization of inpatient resources. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:369-372, 1989Link, Google Scholar

11. Fawcett J, Clark DC, Scheftner WA: The assessment and management of the suicidal patient. Psychiatric Medicine 9:299-311, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fawcett J: Suicide risk factors in depressive disorders and panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 53:9-13, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hilliard JR, Slomowitz M, Deddens JA: Determinants of emergency psychiatric admission for adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1416-1419, 1988Link, Google Scholar

14. Hoehn-Saric R, Hatcher ME, Weiskopf C: Disposition of psychiatric emergency patients: patient characteristics associated with hospitalization. Annals of Emergency Medicine 9:605-609, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. McNeil DE, Myers RS, Zeiner HK, et al: The role of violence in decisions about hospitalization from the psychiatric emergency room. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:207-212, 1992Link, Google Scholar

16. Lewis G, Appleby L, Jarman B: Suicide and psychiatric services. Lancet 344:822, 1994Google Scholar

17. Lewis G, Hawton K, Jones P: Strategies for preventing suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:351-354, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235-1239, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Tejedor MC, Diaz A, Castillon JJ, et al: Attempted suicide: repetition and survival-findings of a follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:205-211, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Isometsa ET, Lonnqvist JK: Suicide attempts preceding completed suicide. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:531-535, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. IASP Executive Committee: IASP guidelines for suicide prevention. Crisis 20:155-163, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar