Predicting Incarceration of Clients of a Psychiatric Probation and Parole Service

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed the extent to which clinical characteristics, psychiatric status, and use of mental health services explain incarceration for technical violations of probation or parole rather than incarceration for new offenses. METHODS: A total of 250 clients of an urban psychiatric probation and parole service were screened for psychiatric diagnoses and monitored with a 12-month data collection protocol. Longitudinal analysis was used to explain incarceration on new charges, incarceration on technical violations of probation and parole, or absence of incarceration. RESULTS: Eighty-five individuals (34 percent) were incarcerated during the follow-up period. Forty-four (18 percent) were incarcerated for a new offense, and 41 (16 percent) were incarcerated for a technical violation. Participation in mental health treatment was associated with a lower risk of incarceration for a technical violation. Intensive monitoring by mental health providers, such as through case management and medication management, were significant risk factors for incarceration for a technical violation. Clients who were incarcerated for a technical violation were more than six times as likely to have received intensive case management services. CONCLUSIONS: The role of mental health services in reducing the risk of incarceration remains mixed. Providing services that emphasize monitoring tends to increase the risk of incarceration for technical violations of criminal justice sanctions. However, any participation in treatment and motivation to participate in treatment appears to reduce the risk of incarceration.

According to the criminalization hypothesis, more restrictive involuntary hospitalization criteria have increased the use of criminal arrest as a management strategy for persons who have severe mental illness (1,2,3). Although longitudinal data to test this assumption are lacking (2,4), a large number of individuals with severe mental illness are involved with the criminal justice system (5,6,7,8,9,10,11). It was recently estimated that 16 percent of jail inmates and 16 percent of persons on probation have a mental illness (5). These statistics raise the question of whether jails are being used as an alternative to treatment for persons who have severe mental illness.

We studied one aspect of this hypothesis—the decision to incarcerate persons who are in violation of stipulations of probation or parole. For those who are mentally ill, probation or parole stipulations frequently include compliance with prescribed psychiatric medication and specific housing arrangements. Noncompliance with these treatment stipulations may result in incarceration. Recent research on involvement in mental health treatment among probationers and parolees with psychiatric disorders has shown that more intensive treatment monitoring seems to result in a greater chance of incarceration for these clients.

This finding could be attributed to greater surveillance and awareness of violations of conditions of probation or parole by case managers and other mental health care providers. Through this process, mental health providers augment the monitoring function of probation and parole officers (12). Intensive supervision of probation or parole has been associated with a higher rate of incarceration as a result of more frequent observation and a greater scope of surveillance (13,14,15).

Solomon and Draine (11) found that case managers used reincarceration as a mechanism for obtaining needed treatment for psychiatric probationers and parolees who were perceived to be decompensating, were unwilling to sign a voluntary admission for hospitalization, and were unable to be committed on an involuntary order because of restrictive admission criteria. It was easier for the case managers to reincarcerate these clients on a technical violation than to hospitalize them. Given that the jail system under study had a well-developed mental health treatment program, the case managers could be reasonably assured that the clients would receive psychiatric treatment.

Investigators who have examined factors that explain reincarceration of mentally ill offenders have concluded that these explanatory factors are the same as for non-mentally ill offenders—that is, sociodemographic characteristics and criminal history (16,17,18). Even in a study of a group of offenders with severe psychiatric illness, Feder (19) found that psychiatric treatment variables did not explain rearrest. However, she did find that although mentally ill offenders were less likely to be reincarcerated, they were more likely to have committed a technical violation. Other researchers have found that rates of technical violations were related to the interaction of the offenders' degree of psychopathology and their diagnosis (20).

These findings suggest that among mentally ill offenders, characteristics of the psychiatric illness and treatment variables both may explain reincarceration for a technical violation. If jails are used as treatment facilities for mentally ill offenders, it is likely that characteristics of the psychiatric illness and patterns of mental health service use will explain reincarceration for technical violations of probationers and parolees and not explain reincarceration for a new offense.

This study assessed whether the incarcerations that took place during a 15-month study period in a population of persons with mental illness who were on probation or parole occurred more for reasons of noncompliance with stipulated psychiatric treatment than for new criminal activities. Specifically, the investigators hypothesized that among psychiatric clients who were on probation or parole, clinical characteristics, psychiatric status, and use of mental health services would be associated with incarceration for a technical violation and not for a new offense when sociodemographic characteristics and criminal history were controlled for.

Methods

Setting

The setting for the study was the probation and parole system of a large city on the East Coast of the United States. This county probation and parole system supervises individuals who are sentenced to probation or who are paroled from sentences of less than two years. Under this system, the distinction between community supervision for probation and parole is minimal. Both probation and parole are supervised by the same officers using the same procedures.

At the time of the study, two specialized probation units were assigned psychiatric cases. Because these units did not provide clinical services, the "psychiatric" designation was an administrative one rather than a clinical one. Clients were assigned to the psychiatric units for a variety of reasons, including at the discretion of sentencing judges. Many clients were assigned to psychiatric probation or parole because they had a history of mental health treatment.

Recruitment of study participants

Because of the heterogeneity of the population on psychiatric probation or parole, potential study participants were screened with a standardized diagnostic tool to determine their history of serious mental illness. The researchers attempted to screen and interview each new client assigned to psychiatric probation or parole. New clients were defined as those who were newly sentenced to probation; newly paroled clients; current clients receiving a new, additional probation sentence; or continuing clients returning to community supervision after a stay in jail.

The researchers were present at the psychiatric probation and parole offices from January 1995 to July 1997 to monitor intakes. The four investigators over the course of the study were the second author, two doctoral students in social welfare who had professional experience in the criminal justice system, and a full-time study coordinator with Ph.D.-level training in ethnographic research methods. An attempt was made to contact each new client until a sample of 250 was obtained. New clients were approached in the office or were referred to the researchers by probation and parole officers.

The researchers kept a running list of new referrals to the psychiatric probation and parole units. New referrals over the recruitment period totaled 1,006. The study participants had to be actively supervised by officers to be eligible for the study. Thus the researchers concentrated their recruitment efforts on clients who were reporting to psychiatric probation and parole offices. They monitored the sign-in logs for names of clients from the new referral list and approached clients in the waiting area or asked officers to refer clients for the study. A total of 440 clients were asked to consent to participate in the screening interview. Of these, 327 (74 percent) consented to be screened for the study.

The only data collected for clients who refused to participate in the study were observer estimates of age, sex, and ethnicity. There were no differences in these characteristics between participants and those who refused to participate. Clients who provided voluntary informed consent were briefly interviewed and then screened for lifetime diagnoses of depression, mania, and schizophrenia with the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule (QDIS) (21,22,23), which is an abridged computerized version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. The interviewer read QDIS items to the study participants and entered their responses directly into the computerized program on a notebook computer. Individuals who screened positive for lifetime occurrences of major depression, mania, or schizophrenia were asked to consent to participate in the study.

Follow-up data collection

The sample of 250 was monitored with use of a protocol that included interviews with the client and with probation and parole officers about each client every three months for one year or until the client was incarcerated, whichever came first. The client interview assessed quality of life, service use, motivation to cooperate with criminal justice stipulations and mental health treatment, substance use, and mental health status.

Informed consent procedures that had been approved by the institutional review board were used for both the screening phase and the follow-up phase of the study. At each subsequent interview point, clients were reminded of their right to refuse to continue to participate in the study without affecting their legal or treatment status. The clients' incarceration data were tracked for 15 months—three months beyond the one-year interview. Data were obtained for all clients from at least one time point; one or more expected waves of data were missing for 98 clients (39 percent).

Symptoms were assessed with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (24,25). Interviewers were trained to agreement with one another on the use of the BPRS. The entire interview period was used for rating observations. The interviewer probed for objective symptom reports at the end of the interview. Subscales were constructed for anxiety and depression, thought disturbance, and hostility (26).

The sections on the severity of drug and alcohol use from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (27,28) were used to assess addiction. Client responses were anchored by using the calendar follow-back method to improve the validity of reports of substance use (29). Cutoff scores for drug and alcohol problems were estimated with the use of patterns of responses to the ASI items that would indicate a clinically significant problem with drug or alcohol use for individuals with severe mental illness.

A measure of attitudes toward psychiatric medication was also used (30). This measure was a modification of a self-report scale of medication compliance developed by Hogan and colleagues (31). Clients were also asked about their participation in psychiatric treatment and compliance with probation or parole supervision.

Interviews with officers included assessments of the severity of substance use developed for clinicians' use (32) and assessments of dangerousness to self or others, grave disability, and lack of impulse control (33,34). These latter assessments were included because they indicate criteria for involuntary hospitalization, which may be an alternative to incarceration. The officers were also asked questions that paralleled the questions asked of clients about the clients' motivation to participate in treatment, to comply with the terms of probation or parole, or to take psychiatric medications.

A list of 24 strategies an officer might use in working with a client who has a mental health problem was included. The officers were asked whether they had used each strategy in the previous three months. These items covered strategies that focused on monitoring, access to treatment, and coercion.

Criminal justice system databases were checked regularly for incarcerations. Several sources of information were used to determine whether incarcerations were for new charges or for technical violations. They included reports filed by officers as well as open-ended interviews conducted with both clients and officers about each incarceration. Information from these sources was analyzed to allow each incarceration to be classified as being primarily for a new charge or for a technical violation.

Analysis

For the purposes of analysis, variables were conceptualized in terms of eight conceptual blocks: sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, criminal history, service use during the follow-up period, motivation to comply with treatment and probation or parole, symptoms, officers' reports, and officers' strategies. The sociodemographic variables were age, male sex, education, African-American ethnicity—a majority of the sample—and never married. The clinical variables were diagnosis of schizophrenia, diagnosis of depression, diagnosis of mania, self-reported psychiatric treatment before first lifetime arrest, self-reported previous psychiatric hospitalization, and self-reported alcohol or drug problem.

The criminal history variables were three or more self-reported previous lifetime arrests and self-reported arrest as a juvenile. Variables related to service use during the follow-up period were any reported use of inpatient hospitalization, emergency services, medical care, therapy, vocational services, substance abuse treatment, or intensive case management. Variables related to motivation to comply with treatment and probation were self-reported lack of compliance with probation or medication, self-reported low motivation for compliance with medication, mental health treatment or probation, and a low rating by the client of the helpfulness of psychiatric medication.

Symptom variables were significant severity ratings for alcohol and drug addiction on the ASI and significant ratings for anxiety and depression, thought disturbance, and hostility on the BPRS. Characteristics of officers' reports were lack of compliance with medications or the stipulations of probation or parole or observed low motivation for compliance with medication, mental health treatment, or probation or parole and officer assessments of client's danger to self, danger to others, grave disability, or lack of impulse control. Finally, the characteristics of officers' strategies were any officer report of routine supervision strategies, collaboration with mental health professionals to supervise the mutual client, a threat to incarcerate the client, and an attempt to hospitalize the client involuntarily.

The first analysis was designed to determine the factors associated with incarceration for new criminal behavior. The purpose of the second analysis was to identify factors associated with technical violations of probation. Both analyses used the group that had no arrests for comparison. Bivariate associations were assessed with chi square analyses (35).

Multivariate prediction models were fitted with use of proportional hazards regression. This longitudinal analysis accounted for time and censored for clients who were not incarcerated over the follow-up period (36). Variables were dichotomized at clinically significant cutoff points for ease of interpretation of resulting risk ratios. Stepwise models were constructed by using variables from the conceptual blocks as potential factors.

The first proportional hazards model predicted any incarceration for a new charge compared with no incarceration, excluding clients who were incarcerated for technical violations. The second model predicted any incarceration for a technical violation, excluding those who were incarcerated for a new charge. Logistic regression was used to directly compare clients incarcerated on a new charge with those incarcerated on a technical violation. To prevent cases from being excluded from the multivariate analyses, means replacement (by arrest group) was used to account for item nonresponse (37). Effect size was assessed by risk ratios (proportional hazards) and odds ratios (logistic). Statistical significance of the effect was assessed with the Wald chi square statistic (38). The statistical package SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

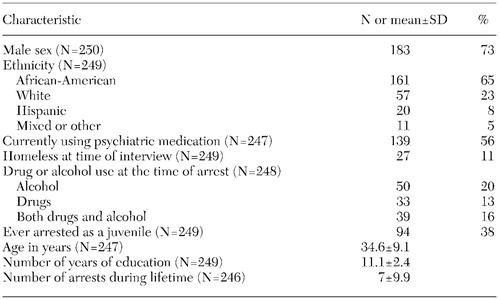

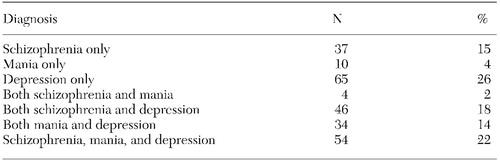

Of the 327 clients screened for lifetime occurrences of major depression, mania, or schizophrenia, 254 (78 percent) screened positive for one or more of these illnesses and thus were eligible for the study. Four eligible clients refused to give consent. Sociodemographic and other characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The results of the QDIS are summarized in Table 2.

Probation officers provided detailed case information for 197 clients. Among the 180 for whom complete data from officers were provided, 159 (88 percent) were on probation and 40 (22 percent) were on parole. Nine (5 percent) were on both probation and parole. In 78 of the 191 cases for which data were available (41 percent), this was the client's first experience with either probation or parole; of these, 76 were on probation and two were on parole.

Of the 250 clients in our sample, 85 (34 percent) were incarcerated within 15 months of the baseline interview, which is consistent with rearrest rates of 24 to 56 percent found among individuals with mental illness (39). Of these incarcerations, 41 (16 percent of the sample) were for technical reasons and 44 (18 percent) were for new criminal charges.

Clients reported using a substantial mix of psychiatric services when they were living in the community. Of the 250 clients, 100 (40 percent) were hospitalized during the follow-up period, and 77 (31 percent) reported receiving psychiatric crisis services. A total of 169 (68 percent) reported receiving any individual, family, or group therapy at some point. Ninety-seven (39 percent) reported receiving substance abuse treatment, and 78 (31 percent) reported receiving intensive case management.

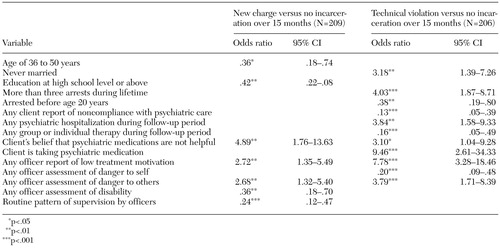

As indicated in Table 3, three variables were predictive of both incarceration on a new charge and arrest for a technical violation in the multivariate models. Participants who doubted the helpfulness of psychiatric medications were almost five times as likely to be incarcerated for a new charge than not incarcerated at all and three times as likely to be incarcerated on a technical violation than not incarcerated.

Clients for whom officers reported low treatment motivation were nearly eight times as likely to be incarcerated on a technical violation than not to be incarcerated and almost three times as likely to be incarcerated for a new charge than not incarcerated. In both categories, officers' assessment of dangerousness to others was a significant risk factor for incarceration.

Four variables were associated with incarceration for a new charge but not with incarceration for a technical violation. Middle to older age (age 36 to 50 years), higher educational attainment, officers' assessment of disability, and a routine pattern of client supervision by officers were all associated with a lower risk of incarceration for a new charge.

Eight variables were associated with incarceration on a technical violation but were not associated with incarceration for a new charge. Four of these variables were associated with a greater risk of incarceration for a technical violation. Individuals who had never been married, who had been incarcerated more than three times during their lifetime, or who had any psychiatric hospitalization during the follow-up period were three to four times as likely to be incarcerated for technical reasons than not to be incarcerated.

Participants who had been prescribed psychiatric medication were more than nine times as likely to be incarcerated on a technical violation than not incarcerated at all. A first arrest before the age of 20 years; any client report of noncompliance; receipt of any individual, family, or group therapy; and officers' assessment of danger to self were associated with a lower risk of incarceration on a technical violation.

In the logistic regression analysis that directly compared clients who were incarcerated for new charges with those who were incarcerated for a technical violation of probation, two variables showed significant differences. Clients who were incarcerated on a technical violation were six times as likely to have received any intensive case management services (odds ratio=6.09, 95% CI=1.7 to 21.7; χ2= 8.34, df=1, p<.01) and more likely to have had high scores on the hostility subscale of the BPRS (odds ratio=3.0, 95% CI=1.1 to 7.9; χ2=4.86, df=1, p<.05) than those who were incarcerated for a new charge.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study support the hypothesis that among clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service the use of mental health services would explain incarceration for technical violations. Services seem to have an inconsistent effect on incarceration for technical violations. Engagement in any form of therapy and client-reported noncompliance with mental health treatment appeared to protect against incarceration for a technical violations, whereas taking a prescribed medication, being hospitalized during the follow-up period, and receiving intensive case management services were associated with a higher likelihood of incarceration for a technical violation. These apparent inconsistencies can be reconciled in the context of the functions of probation and parole.

A primary function of probation and parole officers is monitoring stipulations of probation and parole, which include compliance with psychiatric treatment. Mental health providers, particularly case managers, can enhance the monitoring of persons who are on probation. Medication prescription protocols require clients to make visits to mental health services for medication checks. Similarly, the nature of intensive case management services means observing clients' appointment-keeping behavior as well as their engagement in behaviors that could lead to new criminal charges. Recent release from a psychiatric hospital probably triggers greater monitoring of clients' behavior by mental health care providers. Thus failure to keep appointments and engagement in activities that may lead to criminal behavior may result in mental health care providers' contacting probation and parole officers about noncompliance.

In some cases, providers cooperate with officers to leverage compliance under threat of incarceration. Previous research has shown that officers who interact with mental health care providers are more likely to use threats of incarceration with their clients (40). Such threats may escalate to the point that the officer initiates incarceration.

The result for reports of noncompliance initially appears counterintuitive. It is easier to understand this result in terms of reduced monitoring opportunity than in terms of noncompliance. Noncompliance means that clients were at least participating in mental health services, but not at the expected level. Consequently there is less opportunity for mental health providers to observe activities that violate the client's probation or parole stipulations.

Marginal engagement in mental health services may also reduce the incentive for officers to monitor these clients as closely, and hence they may leave the monitoring to the mental health system. Officers may be comfortable knowing that they can document at least some level of participation in mental health services, which may explain the lack of routine supervision by the officers, in turn explaining incarceration on technical violations. This approach may have implications for mandated services more generally. Although the mandate may provide incentives for clients to be nominally involved in treatment, it cannot explain the quality or the depth of the treatment.

Probation and parole officers help their clients avoid criminal behavior. Incarceration for a technical violation may be used as a preventive measure to keep clients from engaging in criminal behavior that could result in an incarceration for a new charge. Officers who view mental health treatment for these clients as a means of reducing criminal behavior may resort to incarceration as a strategy for treatment and greater subsequent compliance with treatment after release from jail.

Consistent with this reasoning is the finding that clients with low motivation and more negative attitudes about mental health treatment had a greater likelihood of being incarcerated for a technical violation. These negative attitudes were also associated with incarceration for a new charge. This finding seems to indicate that a lack of engagement with mental health services is associated with continued criminal behavior.

As in previous research, clinical characteristics did not play a role in either type of incarceration, but psychiatric status, specifically dangerousness to others, was related to both incarceration for a technical violation and incarceration for a new criminal charge, and dangerousness to self was protective against a technical violation.

The association between dangerousness to others and incarceration for a technical violation can readily be understood in terms of yet another function of officers—protecting public safety. Given that the jail in this study had a comprehensive mental health treatment system, including inpatient psychiatric beds, it is likely that clients who were dangerous to others would have received treatment if they had been sent to the jail. This mental health system has strict commitment criteria. Consequently case managers may find it easier to obtain hospitalization for their clients in the jail (41).

Consistent with previous research on reincarceration, criminal history was related to incarceration for a technical violation but did not predict incarceration for a new charge. A client's criminal history probably influences officers' decisions about technical violations. Officers thus may use incarceration for a technical violation as a strategy to prevent criminal behavior that will ultimately result in a new criminal charge.

Also paralleling the results of previous research, sociodemographic characteristics helped explain both types of incarceration, but these characteristics differed for each type. Clients who went to jail for a technical violation were less likely to have ever been married. Persons on probation who have fulfilled fewer social expectations may not have the attendant social networks to support treatment or compliance with conditions of probation or parole. Thus officers may need to resort to other strategies to encourage compliance with treatment.

On the basis of these findings it appears that incarceration for a technical violation is not being used pervasively for treatment purposes, although it does occur. This type of incarceration is used more to control the client and as a strategy for encouraging clients to comply with treatment when they are living in the community under court stipulations. In some cases mental health providers and probation and parole officers work together toward clinical goals for the client. These alliances between the mental health system and the criminal justice system are not formally structured but occur on an ad hoc basis. If formalized arrangements between the mental health and criminal justice systems are pursued, policy planners will need to carefully weigh the benefits of service coordination against the clients' increased risk of incarceration.

Criminal justice systems vary in the extent to which they have specialized probation and parole units. Future research could examine the interaction between mental health services and probation and parole agencies in several service contexts. As we gain a better understanding of this interactive process, interventions or service models may be developed. Such approaches could provide an opportunity for studies of these service innovations. The implications of this and related research would tap into the current interest in outpatient commitment and mental health courts.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant R01-MH-54445 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Jonathan David, Ph.D., in coordinating data collection and Kim Nieves, M.S.W., in data collection and management. The authors thank Tony Sasselli, Fran Ronkowski, and Jim Rubolina.

Dr. Solomon is professor and Dr. Draine is assistant professor in the school of social work and the department of psychiatry of the University of Pennsylvania, 3701 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Marcus is an associate of the Social Work Mental Health Research Center of the School of Social Work, University of Pennsylvania. This study was conducted in collaboration with the adult probation and parole units of the First Judicial District of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service

|

Table 2. Psychiatric diagnoses of 250 clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service, as determined by the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule

|

Table 3. Odds ratios of incarceration for a new charge versus no incarceration and incarceration for a technical violation versus no incarceration in a sample of mental health clients on probation and parole, as determined by a proportional hazards model

1. Abramson M: The criminalization of mentally disordered behavior. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 23:101-105, 1972Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Teplin L: The criminalization of the mentally ill: speculation in search of data. Psychological Bulletin 94:54-67, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Teplin L: The criminalization hypothesis: myth, misnomer, or management strategy? In Law and Mental Health: Major Developments and Research Needs. Edited by Shah SA, Sales BD. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

4. Hiday VA: Civil commitment and arrests: an investigation of the criminalization thesis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:184-191, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Ditton PM: Mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

6. Teplin LA: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. American Journal of Public Health 80:663-669, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Mentally disordered women in jail: who receives services? American Journal of Public Health 87:604-609, 1997Google Scholar

8. Guy E, Platt JJ, Zwerling I, et al: Mental health status of prisoners in an urban jail. Criminal Justice and Behavior 12:29-53, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Lamb HR, Grant RW: The mentally ill in an urban county jail. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:17-22, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lamb HR, Grant RW: Mentally ill women in a county jail. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:363-368, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Solomon P, Draine J: Issues in serving the forensic client. Social Work 40:25-33, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

12. Solomon P, Draine J: One year outcomes of a randomized trial of case management with seriously mentally ill clients leaving jail. Evaluation Review 19:256-273, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Gottfredson MR, Mitchell-Herzfeld SD, Flanagan TJ: Another look at the effectiveness of parole supervision. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 19:277-298, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Martin SS, Scarpitti RF: An intensive case management approach for paroled IV drug users. Journal of Drug Issues 23:43-59, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Tonry M: Stated and latent functions of ISP. Crime and Delinquency 36:174-191, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Bonta J, Law M, Hanson K: The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 123:123-142, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Feder L: A profile of mentally ill offenders and their adjustment in the community. Journal of Psychiatry and the Law 19:79-98, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Schellenberg EG, Wasylenski D, Webster D: A review of arrests among psychiatric patients. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:251-264, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Feder L: A profile of mentally ill offenders and their adjustment in the community. Journal of Psychiatry and the Law 19:79-98, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Toch H, Adams K: Pathology and disruptiveness among prison inmates. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 23:7-21, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Bucholz KK, Marion SL, Shayka JJ, et al: A short computer interview for obtaining psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatric Services 47:293-297, 1996Link, Google Scholar

22. Bovings L, Helzer J, Croughan J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381-389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Spengler P, Wittchen HU: Procedural validity of standardized symptom questions of psychotic symptoms: a comparison of the DIS with two clinical methods. Comprehensive Psychiatry 29:309-322, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Overall J, Gorham D: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812Google Scholar

25. Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein K: Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin 12:578-602, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Guy W: ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, revised ed. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1976Google Scholar

27. Zanis DA, McLellan AT, Corse S: Is the Addiction Severity Index a reliable and valid instrument among clients with severe and persistent mental illness and substance use disorders? Community Mental Health Journal 33:213-227, 1997Google Scholar

28. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412-422, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, et al: The timeline follow-back reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:134-144, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Sullivan G: Rehospitalization of the seriously mentally ill in Mississippi: Conceptual Models, Study Design, and Implementation. Santa Barbara, Calif, Rand, 1989Google Scholar

31. Hogan TP, Awad AG, Eastwood R: A self-report scale predictive of drug compliance in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 13:177-183, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Drake R, Osher F, Wallach M: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia: a prospective community study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:408-414, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Segal S, Watson M, Goldfinger S, et al: Civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room: I. the assessment of dangerousness by emergency room clinicians. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:748-752, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Segal S, Watson M, Goldfinger S, et al: Civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room: III. disposition as a function of mental disorder and dangerousness indicators. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:759-763, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Rosner B: Fundamentals of biostatistics, 4th ed. Belmont, Mass, Duxbury, 1995Google Scholar

36. Allison PD: Survival analysis using the SAS system: a practical guide. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

37. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S: Applied logistic regression. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

38. Taylor MA, Amir N: The problem of missing clinical data for research in psychopathology: some solution guidelines. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:222-229, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Hiday VA: Mental illness and the criminal justice system, in A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health. Edited by Horwitz A, Scheid T. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1999Google Scholar

40. Draine J, Solomon P: Threats of incarceration in a psychiatric probation and parole service. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 71:262-267, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Solomon P, Rogers R, Draine J, et al: Interaction of the criminal justice system and psychiatric professionals in which civil commitment standards are prohibitive. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 23:117-128, 1995Medline, Google Scholar