Effects of Commonly Used Benzodiazepines on the Fetus, the Neonate, and the Nursing Infant

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite the widespread use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy and lactation, little information is available about their effect on the developing fetus and on nursing infants. The authors review what is currently known about the effects of benzodiazepine therapy on the fetus and on nursing infants. METHODS: A MEDLINE search of the literature between 1966 and 2000 was conducted with the terms "benzodiazepines," "diazepam," "chlordiazepoxide," "clonazepam," "lorazepam," "alprazolam," "pregnancy," "lactation," "fetus," and "neonates." RESULTS: Currently available information is insufficient to determine whether the potential benefits of benzodiazepines to the mother outweigh the risks to the fetus. The therapeutic value of a given drug must be weighed against theoretical adverse effects on the fetus before and after birth. The available literature suggests that it is safe to take diazepam during pregnancy but not during lactation because it can cause lethargy, sedation, and weight loss in infants. The use of chlordiazepoxide during pregnancy and lactation seems to be safe. Avoidance of alprazolam during pregnancy and lactation would be prudent. To avoid the potential risk of congenital defects, physicians should use the benzodiazepines that have long safety records and should prescribe a benzodiazepine as monotherapy at the lowest effective dosage for the shortest possible duration. High peak concentrations should be avoided by dividing the daily dosage into two or three doses. CONCLUSIONS: Minimizing the risks of benzodiazepine therapy among pregnant or lactating women involves using drugs that have established safety records at the lowest dosage for the shortest possible duration, avoiding use during the first trimester, and avoiding multidrug regimens.

Benzodiazepines are one of the most commonly used groups of anxiolytic drugs in the United States and are among the drugs most frequently prescribed to women of reproductive age and to pregnant women (1) for reducing anxiety and managing preeclampsia or eclampsia in the latter part of pregnancy. These agents are also indicated for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, sedation, light anesthesia and anterograde amnesia of perioperative events, control of seizures, and skeletal muscle relaxation. Benzodiazepines are used commonly, even in the absence of complete knowledge of their potential adverse effects.

Benzodiazepine compounds fall into three major categories: long-acting compounds—diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, chlorazepate, flurazepam, halazepam, and prazepam; intermediate-acting compounds—clonazepam, lorazepam, quazepam, and estazolam; and short-acting compounds—alprazolam, oxazepam, temazepam, midazolam, and triazolam. The most commonly used benzodiazepines in the United States are diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, lorazepam, and alprazolam.

For nearly all the current benzodiazepines, the physiological action of the drug has not been fully described. The effects of these drugs appear to be mediated through the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The drugs appear to act on the limbic, thalamic, and hypothalamic levels of the central nervous system to produce sedative and hypnotic effects, reduction of anxiety, anticonvulsant effects, and skeletal muscle relaxation. Specific binding sites with high affinity for benzodiazepines have been detected in the central nervous system, and both GABA and chloride enhance the affinities of these sites for the drugs.

All major classes of benzodiazepine compounds can be assumed to be excreted into milk or to diffuse readily across the placenta to the fetus. The amount of a drug excreted depends on the characteristics of the particular drug—plasma protein binding, ionization, the degree of lipophilicity, molecular weight, half-life, maternal blood concentrations, oral bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics. Of these characteristics, the lipid solubility and molecular weight of the drug are the most important determinants of exposure during pregnancy and lactation.

There are many possible risks to the fetus whenever anxiolytic medications are prescribed to pregnant women. The onset of teratogenic effects may be immediate or delayed. Possible effects include abortion, malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, functional deficits, carcinogenesis, and mutagenesis. The risk of malformation is greatest when the fetus is exposed between two and eight weeks after conception. If the drugs are administered at or near term, they may cause fetal dependence and eventual withdrawal symptoms.

In this article we review the risks posed by the most commonly used benzodiazepines during gestation and nursing and the potential long-term effects on the development of the exposed child.

Methods

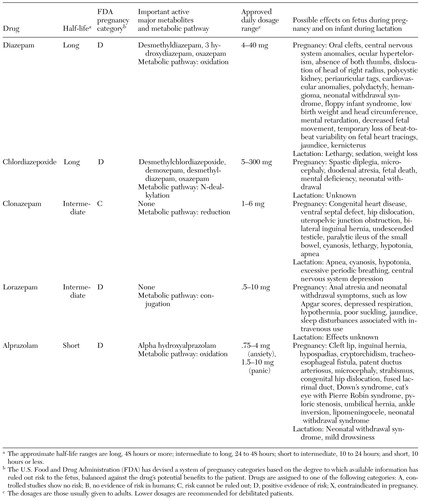

We conducted a MEDLINE search of the literature from 1966 to December 2000 by using the terms "benzodiazepines," "diazepam," "chlordiazepoxide," "clonazepam," "lorazepam," "alprazolam," "pregnancy," "lactation," "fetus," and "neonates." Various combinations of these terms were also used. A total of 118 articles were included in the literature review. These articles were categorized by medication and were assessed in terms of information on risk to the fetus during pregnancy and information on risk to the infant during breast-feeding (Table 1).

Results

Diazepam

Risk to the fetus during pregnancy. Among anxiolytic agents, only diazepam has been systematically studied among pregnant women. Until the early 1980s, diazepam was the most frequently prescribed benzodiazepine in the United States and worldwide (2). Diazepam is indicated for the management of anxiety disorders and for the short-term relief of symptoms of anxiety. In acute alcohol withdrawal, diazepam is useful in the relief of acute agitation; the relief of tremor; management of withdrawal from benzodiazepines or barbiturates; and treatment of hallucinosis. It is also used as a skeletal muscle relaxant, as preoperative medication, and as an adjunct to anticonvulsants in the treatment of seizures.

Diazepam and its major metabolite, N-desmethyldiazepam, which are both pharmacologically active, freely cross the human placenta during early pregnancy as a result of their high lipid solubility (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). After the sixth month of pregnancy, the loss of the cytotrophoblasts—Langerhan's cells—from the placenta further facilitates the transport of diazepam across the placenta (11). Also, diazepam and N-desmethyldiazepam are bound to fetal plasma proteins more extensively than to maternal plasma proteins; maternal protein binding is lower in the pregnant than the nonpregnant state (12,13,14). After either intravenous or intramuscular injection, diazepam was found to cross the placenta rapidly and to reach considerably higher concentrations in cord plasma than in maternal plasma, with a fetal-maternal ratio of 1.2 to 2, during early pregnancy (15,16) and at term (4,17,18,19). Substantial accumulation of diazepam may occur in adipose tissue. High concentrations are also present in the brain, the lungs, and the heart (4).

The lipophilic nature of diazepam (10), its high intake in animal fat tissue (20), its easy penetration into brain white matter, and its long retention in neural tissues in monkeys (21) all suggest that human tissue may act as a depot for diazepam. In most cases the neonate is capable of slowly metabolizing small doses of diazepam (4), although diazepam and its active metabolite may persist for at least a week in pharmacologically active concentrations after administration of high dosages to the mother. The mean plasma half-life in the neonate is about 31 hours (4).

Available data from various epidemiological studies are inconsistent in showing the risk of congenital malformations among children born to women who took diazepam during pregnancy. Several studies found that the use of diazepam during the first trimester of pregnancy was significantly greater among mothers of children born with oral clefts. Aarskog (22) found that 6.3 percent of 30 infants born with cleft palate in the United States between 1967 and 1971 had been exposed to diazepam in the first trimester, compared with 1.1 percent of control infants. These frequencies were significantly different by the Z2 test (p<.015).

This rate of exposure to diazepam among the children with cleft palate was similar to that reported by Saxen (23), who found a rate of exposure of 6.2 percent in a study performed during the same period. Safra and Oakley (24) reported that mothers of infants with cleft lip, cleft palate, or both had used diazepam four times more frequently than mothers of control infants. However, in another article these same authors pointed out that a fourfold increase in oral clefts, if confirmed, imply only a .4 percent risk of cleft lip with or without cleft palate and a .2 percent risk of cleft palate (25). A review of 599 oral clefts by Saxen and Saxen (26) showed a significant association (p<.05) between ingestion of anxiolytics, mostly diazepam, during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Many other epidemiological studies have shown an association between the use of diazepam in the first trimester and oral clefts (23,27,28,29,30). However, these studies were followed by prospective and retrospective studies that did not show a greater risk of congenital malformations (27,31,32,33,34,35). Also, there has been a large increase in the use of diazepam over the past several years, without a concomitant increase in the occurrence of cleft lip or cleft palate.

One case of a congenital absence of both thumbs, including metacarpal bones, and dislocation of the head of the right radius was reported in a newborn whose mother had been given 6 mg of diazepam daily for three weeks and hydroxyprogesterone during pregnancy (36). Also, one case of spina bifida occulta in a newborn whose mother received diazepam and protriptyline for the first four months of pregnancy was reported (37). In both instances, the mothers received drug combinations for which there is no clear or consistent evidence of the contribution of diazepam to these birth defects.

Czeizel and colleagues (38) described a pilot study of 209 pregnant women who were admitted to hospitals between 1960 and 1979 because of intentional drug overdose. The women's pregnancy outcomes were compared with their previous and subsequent pregnancy outcomes. A pediatrician and a psychologist examined 96 index children and their 144 siblings. Of the 96 women whose pregnancies ended in a live birth, eight had used diazepam alone or with other drugs for self-poisoning. Rates of congenital anomalies and central nervous system dysfunction were no higher among the index children. However, two siblings had congenital anomalies.

Cerqueira and associates (39) reported that no permanent adverse effects occurred among the offspring of five pregnant women who received toxic dosages of benzodiazepines in mid- or late pregnancy. One case has been reported of cleft lip and palate, craniofacial asymmetry, ocular hypertelorism, and bilateral periauricular tags in an infant whose mother took a single 580-mg dose of diazepam around the 43rd day of gestation. The authors concluded that the drug was responsible for the defect (40).

In prospective studies of the effect on the infant of maternal use of psychoactive drugs during pregnancy, an embryofetopathy associated with the regular use of benzodiazepines has been described that resembles fetal alcohol syndrome (41,42). Laegreid and colleagues (41) reported a specific "benzodiazepine syndrome" among seven infants with dysmorphism in a prospective study in which 36 mothers of 37 infants regularly took benzodiazepines during pregnancy. Five mothers had taken diazepam, and two mothers had taken oxazepam. The clinical findings of this benzodiazepine syndrome included Möbius syndrome, Dandy-Walker malformation with lissencephaly, polycystic kidney, submucous cleft hard palate, microcephaly, dysmorphism, varying degrees of mental retardation, convulsions, and neonatal abstinence syndrome. However, several other investigators did not accept the existence of this syndrome (43,44).

Low birth weight and small head circumference were reported in a study of 17 infants born to women who took diazepam or other benzodiazepines during pregnancy (45). The weights of these children had normalized by ten months, but the head circumference was still smaller than expected at 18 months (46).

Two studies involving 383 and 390 children showed an association between maternal use of diazepam or related drugs during the first trimester of pregnancy and congenital heart disease and other anomalies—polydactyly and hemangioma (1,47). However, Bracken and Holford (1) reanalyzed these data and did not find a significant association between cardiovascular anomalies and diazepam. Three other studies involving 298, 150, and 90 children did not show an association between maternal use of diazepam during the first trimester of pregnancy and cardiovascular malformations—congenital heart defects, ventricular septal defects, and conotruncal malformations (48,49,50).

Two major syndromes of neonatal complications have been observed among infants exposed to maternal parenteral diazepam for long periods or to dosages exceeding 30 to 40 mg a day, especially intramuscular or intravenous dosages, during pregnancy and labor (6,7,9,51,52,53,54,55). Neonatal withdrawal syndrome has been reported among neonates exposed to diazepam acutely during labor for preeclampsia, eclampsia, and sedation in the mother and has also been seen with more prolonged use of the lower dosages that are commonly prescribed for anxiety disorders (7,53,54,56).

Symptoms of neonatal withdrawal include hypertonia, hyperreflexia, restlessness, irritability, abnormal sleep patterns, inconsolable crying, tremors or jerking of the extremities, bradycardia, cyanosis, suckling difficulties, apnea, risk of aspiration of feeds, diarrhea and vomiting, and growth retardation. This neonatal withdrawal can appear within a few days to three weeks after birth and can last up to several months. Dosages exceeding 30 mg have been associated with a higher incidence of low Apgar scores (56). This syndrome is best minimized by gradually tapering diazepam before delivery.

Several reports have also suggested that the acute use of diazepam, especially intramuscularly or intravenously, during labor may be enough to produce "floppy infant syndrome" (6,52,53,55,57,58). The general features of this syndrome are withdrawal symptoms, hypothermia, lethargy, respiratory problems, and feeding difficulties. All these infants appeared to recover without any long-lasting sequelae. These reports are consonant with known physiological changes in the newborn. Infant free fatty acid concentrations increase during the first days after delivery. This increase translates into a higher proportion of free diazepam and N-desmethyldiazepam and hence a stronger pharmacological effect on the infant.

Other miscellaneous findings are temporary loss of beat-to-beat variability on fetal heart rate tracings (8,9,59) and decreased fetal movements (60) when diazepam or other benzodiazepines have been administered during labor. Schiff and associates (61) presented evidence to suggest that injectable forms of diazepam at delivery may impair bilirubin binding to serum albumin, possibly through competitive binding of a preservative—sodium benzoate—and that this may lead to prolonged hyperbilirubinemia of the newborn and potentially to kernicterus (6,61). Therefore, if parenteral diazepam is used, it is important to check whether sodium benzoate has been added.

In summary, most reviewers have concluded that diazepam is not teratogenic. Although occasional reports have associated the therapeutic use of diazepam with congenital malformation, the bulk of the evidence indicates that the use of diazepam during gestation has no adverse effects on the child's development. Given the extensive clinical experience, diazepam should be considered safe when used at the lowest possible dosage during pregnancy. Diazepam should be avoided, or the dosage tapered, in the weeks before delivery, if possible, because it may cause neonatal withdrawal syndrome, floppy infant syndrome, or various acute toxic effects in the newborn.

Risk to the infant during breast-feeding. There is evidence that diazepam and its metabolite, N-desmethyldiazepam, is excreted in the breast milk of nursing mothers in low concentrations, depending on the dosage (6,9,62,63,64,65,66). However, there have been few case reports of adverse effects associated with the use of diazepam during lactation.

Patrick and colleagues (62) found that oxazepam, an active metabolite of diazepam, was present in the urine of an eight-day-old infant who was nursing from a mother who had received 30 mg of diazepam a day for the previous three days. The infant became lethargic and lost weight within two days after the mother began taking diazepam; these effects resolved after breast-feeding was discontinued. Electroencephalographic recordings showed bursts of rapid activity in the frontal regions and were consistent with the expected effects of a sedative medication.

In another case report, an infant who was exposed to another type of long-acting benzodiazepine—chlordiazepoxide—through breast milk developed similar signs (67). However, Brandt (64) determined that among four women who were taking 10 mg of diazepam a day, drug concentrations in breast milk were too low to adversely affect the infant.

Wesson and associates (68) described a case of a mother who was treated with diazepam throughout pregnancy and for three months postpartum at a dosage varying from 6 to 10 mg a day. She delivered without complications a boy weighing 6 pounds, 15 ounces. The newborn's Apgar score was 9 after one minute, and he was nursed within minutes of birth. The mother breast-fed the infant eight to ten times a day. Sedation of the infant was noted when nursing occurred less than eight hours after the mother took a dose of diazepam. The infant's serum, the mother's serum, and the mother's breast milk were analyzed for diazepam and desmethyldiazepam. The infant's serum drug concentration indicated that an impaired capacity to metabolize diazepam and desmethyldiazepam may occur even when the mother is taking diazepam in the low range of the therapeutic dosage. Laegreid and colleagues (45) also published data showing sedation of infants of mothers who took diazepam up to the time of delivery.

In summary, the long-term use of diazepam by nursing mothers has been reported to cause sedation and lethargy among nursing infants as a result of altered metabolism. These effects may result in feeding difficulties or weight loss in the infant. Physicians should be alert to possible side effects of diazepam among nursing infants. Should these side effects be observed, either breast-feeding or intake of the drug should be discontinued.

Chlordiazepoxide

Risk to the fetus during pregnancy. Chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride is a long-acting benzodiazepine indicated for the management of anxiety disorders, withdrawal symptoms from chronic alcoholism, and preoperative apprehension and anxiety. It also has appetite-stimulating and weak analgesic effects. Chlordiazepoxide has a very low toxicity and is safe for preanesthetic use during labor, even in large intravenous dosages (69).

Chlordiazepoxide is readily transmitted across the placenta, and concentrations in fetal blood are similar to those in maternal circulation (70). There has been one report of congenital malformation associated with the use of chlordiazepoxide during early pregnancy. In an analysis by Milkovich and Van den Berg (71) of 19,044 live births, severe congenital anomalies—spastic diplegia, microcephaly, duodenal atresia, and mental deficiency—occurred more often among infants of mothers who took chlordiazepoxide during the first 42 days of pregnancy than among infants of mothers who took other drugs or no drugs (11.4 per 100 compared with 4.6 per 100 and 2.6 per 100, respectively). Fetal death rates were also higher in the group exposed to chlordiazepoxide than in the control group.

In other studies, the frequency of congenital anomalies was no greater than expected among the infants of women who took chlordiazepoxide during the first trimester of pregnancy (1,47,72,73,74). Hartz and associates (74) conducted a follow-up study of 50,282 pregnancies that lasted for at least five lunar months. Malformations were identified before the first birthday or at death before the fourth birthday among 3,248 children (6.5 percent). A total of 1,870 children who were exposed in utero to chlordiazepoxide were compared with 48,412 children who were not exposed. No significant differences in the occurrence of congenital defects were found in the overall or specific outcomes; rates were also similar when exposures occurred during the first trimester or at other times during pregnancy. Among children who were exposed to chlordiazepoxide in utero, no differences were found in the incidence of motor and mental abnormalities at eight months or in IQ scores at four years (74).

Several other studies showed no association between maternal use of chlordiazepoxide and birth defects. A study of 1,427 infants with congenital anomalies showed no link between birth defects and maternal use of chlordiazepoxide during the first trimester of pregnancy (1). Similarly, no causal relationship was observed with maternal use of chlordiazepoxide early in pregnancy in studies of 390 children with congenital heart disease (47) and 1,201 children with cleft lip, cleft palate, or both (75).

Decaneq and associates (76) described a double-blind, random-selection study in which 200 pregnant women were given 100 mg of chlordiazepoxide or placebo intramuscularly during the first stage of labor. Chlordiazepoxide showed no depressant effects on infants. On this basis, it is thought to be safe to give chlordiazepoxide to parturient women at dosages of up to 100 mg without adversely affecting the newborn.

There have been no reports of adverse effects with the occasional use of chlordiazepoxide in the second and third trimester, and several studies have shown no serious consequences. However, there are three well-documented case reports of neonatal withdrawal syndrome among infants who were either chronically exposed to chlordiazepoxide in utero or exposed to relatively small amounts at parturition (67,77,78). In one case, chlordiazepoxide was prescribed to a mother at a dosage of 25 mg four times a day during pregnancy to decrease mental distress (77). In another case, a patient had been treated with 30 mg of chlordiazepoxide a day for five years because of a moderately severe emotional disorder, and her dosage was lowered to 20 mg a day in the 12th week of pregnancy (78). In the third case, the patient was given 500 mg of chlordiazepoxide intravenously over a period of four hours before cesarean section (86). In all these cases, neonatal withdrawal symptoms appeared within a few days after birth.

Excretion of benzodiazepines is markedly delayed among premature infants. Signs of withdrawal may be noticed only after fetal exposure to the drug. In general, these symptoms appear within a few days to three weeks after birth and can last up to several months. Children affected generally recover without sequelae. Physicians should be aware of the potential for a delayed withdrawal syndrome when caring for infants whose mothers received benzodiazepine compounds—especially diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, triazolam, and alprazolam—during pregnancy. Signs of withdrawal may develop even after the infant has been discharged from the newborn nursery. Clinical observation should be correlated with concentrations of the drug in neonatal blood and umbilical cord serum.

Although there have been occasional reports of adverse effects associated with the therapeutic use of chlordiazepoxide during pregnancy, the bulk of clinical experience with this drug worldwide indicates that pregnant women can be treated with chlordiazepoxide without adverse effects on themselves or their infants. When chlordiazepoxide cannot be avoided, the risk can be reduced by lowering the daily dosage. As with any drug, the possible risks to the mother and the fetus should always be weighed against the potential benefits to the pregnant mother.

Risk to the infant during breast-feeding. Like many other benzodiazepines, chlordiazepoxide is excreted in human milk (62,65,66,79). No published reports on the use of chlordiazepoxide during breast-feeding have established risk. However, similar long-acting benzodiazepine compounds do pass into breast milk and may cause some adverse effects. Thus caution is advised if the drug is used during lactation.

Clonazepam

Risk to the fetus during pregnancy. Clonazepam is a benzodiazepine anticonvulsant that has been available for clinical use since 1973. Among adults, clonazepam is metabolized primarily by hydroxylation, although this metabolic pathway generally is impaired in the newborn. The half-life in adults is 20 to 60 hours. Although the half-life for clonazepam in neonates is not known, the half-lives of other benzodiazepine derivatives are two to four times longer for neonates than for adults (80). No adequate studies have determined the risks of the use of clonazepam by pregnant women to the unborn fetus. There have been some clinical reports of congenital anomalies and other adverse effects among the children of epileptic mothers who took clonazepam alone or with other drugs during pregnancy (80,81,82,83,84,85).

In a study conducted by Eskazan and Aslan (85) in Turkey, 12 of 104 children who had been exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero had various major congenital malformations. Three of these 12 children had been exposed to clonazepam in combination with another type of anticonvulsant drug. Clonazepam was used in two cases with phenobarbital and in one case with primidone and phenytoin. A greater risk of congenital heart disease and hip dislocation was found only for the combination of clonazepam and phenobarbital at dosages varying from 1 to 6 mg a day. It has been speculated that this finding was the result of either combination therapy and multidrug interactions (86) or an increased maternal plasma concentration of the antiepileptic drug (87). In a larger study of 10,698 infants with congenital anomalies, maternal use of clonazepam during pregnancy was not significantly represented (81).

Johnson and colleagues (88) described five cases of major malformations: one infant had a ureteropelvic junction obstruction, two had bilateral inguinal hernias, one had an undescended testicle that required orchidopexy when the child was four years old, and one had a ventricular septal defect and bilateral inguinal hernias (89). Haeusler and associates (82) also described a case of paralytic ileus of the small bowel that was diagnosed in a fetus at 32 weeks after referral because of polyhydraminos. The mother had taken clonazepam and carbamazepine for epilepsy for the entire pregnancy. All known causes for the ileus were ruled out, and by 20 months the boy had developed normally. The authors concluded that maternal intake of clonazepam was probably the cause of the paralytic ileus.

There has been one case report of neonatal toxicity associated with maternal clonazepam therapy. Fisher and colleagues (80) described a 40-year-old multiparous mother with myoclonic sleep disorder who was treated with clonazepam throughout pregnancy and delivered a female infant who weighed six pounds at 36 weeks. The infant's Apgar scores were 8 and 9 at one and five minutes, respectively. At six hours, several episodes of apnea with cyanosis occurred with lethargy and hypotonia. No congenital malformations were present, and these adverse effects resolved within ten days after birth.

Follow-up at five months revealed no neurologic abnormalities. The mother's serum clonazepam concentration at delivery was 32 ng/mL, and the infant's cord blood clonazepam concentration was 19 ng/mL (the therapeutic range is 5 to 70 ng/mL). Breast-milk clonazepam concentrations were measured when nursing began 72 hours after birth and periodically until discharge on the 14th day. The concentration in breast milk was constant between 11 and 13 ng/mL. The ratio of breast milk concentration to maternal serum concentration was about 1 to 3. No evidence of drug accumulation after breast-feeding was found. Excessive periodic breathing was observed until ten weeks; the authors were unable to determine whether breast-feeding contributed to this effect (80).

A similar kind of toxicity—respiratory depression—was also found in a newborn whose mother had been treated with 5.5 mg of clonazepam a day throughout the pregnancy and after delivery (83). Lethargy and hypotonia were noted in other infants whose mothers took diazepam during pregnancy (53). It is recommended that infants of mothers who received clonazepam during pregnancy or while nursing have their serum drug concentrations monitored. The infants should be monitored for central nervous system depression or apnea. In general, clonazepam should be used during pregnancy only if the clinical benefit to the mother justifies the risks to the fetus.

Risk to the infant during breast-feeding. As with many other benzodiazepines, clonazepam is excreted in human milk (80,90,91). We found no published studies on the use of clonazepam during breast-feeding, apart from the case report described above. Infants who are exposed to clonazepam during nursing should be monitored for central nervous system depression or apnea. However, caution should always be advised when clonazepam is administered to nursing mothers.

Lorazepam

Risk to the fetus during pregnancy. Lorazepam belongs to a group of 1,4-benzodiazepam derivatives that have a higher potency than the drugs that belong to the closely related chlordiazepoxide group of derivatives. Lorazepam is used in comparatively small dosages—1 to 4 mg a day for adults—as a broad-spectrum tranquilizer for the treatment of anxiety and physical tension, for insomnia in association with anxiety, as an effective anticonvulsant, and for premedication before surgical anesthesia (92).

One useful property of lorazepam is its prolonged amnestic action during labor. Its use has been suggested for pregnancy-related hypertension, for which a similar drug—diazepam—has also been used. Lorazepam and its pharmacologically inactive glucuronide metabolite do not cross the placenta as easily as other benzodiazepines, such as diazepam, and do not have the long-lasting effects on the newborn that occur with diazepam and nitrazepam (8). Several studies have shown that cord plasma concentrations of lorazepam were generally lower than the corresponding maternal concentrations (93,94).

Lorazepam has a half-life of about 12 hours in adults, which is appreciably shorter than that of diazepam. Lorazepam is metabolized predominantly to a pharmacologically inactive glucuronide that does not accumulate in the tissues. Thus lorazepam seems to be a better alternative for sedation and relief of anxiety during normal delivery and before cesarean section than diazepam. Lorazepam's elimination from the newborn is slow—term babies continue to excrete detectable amounts for up to eight days (95). Elimination of several other benzodiazepines is even slower in premature infants (96).

No epidemiological studies have reported congenital anomalies in infants whose mothers were treated with lorazepam during pregnancy. However, Godet and colleagues (97) described a study in which 187 malformed infants were observed among 100,000 births that involved exposure to benzodiazepines, including lorazepam, during the first trimester of pregnancy. A significant association was found between lorazepam and anal atresia (five cases, p<.001).

There have also been occasional case reports of neonatal toxicity associated with the use of lorazepam. Whitelaw and associates (95) described 53 infants born to 51 mothers who were treated with lorazepam for hypertension at term. Thirty-five mothers were treated with oral lorazepam at dosages ranging from 1 mg twice daily to 2.5 mg three times daily for mild to moderate hypertension. Sixteen women were treated with a continuous infusion of 8 mg of lorazepam in 500 mL of 5 percent dextrose solution for fulminating hypertension. All were observed for five days after delivery.

Full-term neonates whose mothers had received oral lorazepam had no complications apart from a slight delay in establishing feeding. Intravenous use of lorazepam for severe hypertension was associated with neonatal withdrawal and significantly low Apgar scores, hypothermia, poor suckling, and depressed respiration that required ventilation. Preterm babies whose mothers had been given lorazepam by either route had higher incidences of low Apgar scores, need for ventilation, hypothermia, and poor suckling. Thus the effects of lorazepam on neonates indicate that intravenous use at any stage of pregnancy and oral use before 37 weeks should be restricted to hospitals that have facilities for neonatal intensive care.

In addition, lorazepam's short half-life could increase the risk of neonatal withdrawal. When possible, tapering the dosage of lorazepam—and any benzodiazepine—gradually before the expected delivery date can help prevent neonatal withdrawal. Also, the use of flumazenil, a benzodiazepine antagonist, can alleviate fetal or neonatal toxicity (98). Several other reports have noted respiratory depression, jaundice (99), irritability, neonatal hypotonia, groaning, sleep disturbances, and feeding difficulties among infants born to mothers who were treated with lorazepam late in pregnancy (99,100,101).

Majer and Green (102) described a case report of bleeding due to a lack of fibrinogen in a newborn whose mother was taking lorazepam. The mother had been taking 125 mg of phenytoin and 200 mg of sodium valproate three times a day and 1 mg of lorazepam at night throughout her pregnancy. There was no family history of a bleeding disorder, and the infant died two days after birth. Both parents had normal fibrinogen concentrations. During this mother's second pregnancy, sodium valproate was discontinued without a change in the phenytoin or lorazepam, and oral vitamin K was started in late pregnancy. The second delivery was free of difficulties, and the infant had a normal fibrinogen concentration. The authors concluded that the first infant's lack of fibrinogen was due to sodium valproate rather than to lorazepam.

In summary, injectable lorazepam should not be used during pregnancy. The manufacturer does not recommend preoperative use of the injection for obstetric procedures, such as cesarean section, or during labor and delivery, because safety of the injection has not been established for such procedures (103). Oral lorazepam should be used during pregnancy only in life-threatening situations or in cases of severe disease for which safer drugs cannot be used or are ineffective. When lorazepam is administered during pregnancy, or if the patient becomes pregnant while receiving the drug, the patient should be advised of the potential hazard to the fetus, and the drug should be discontinued if possible.

Risk to the infant during breast-feeding. Lorazepam is excreted into breast milk in low concentrations (95,104,105). No adverse effects associated with the use of lorazepam by the mother have been reported among nursing infants. Summerfield and Nielsen (104) studied lorazepam as premedication in four breast-feeding mothers who were scheduled for postpartum sterilization. All the women, each weighing more than 55 kg, were premedicated with 3.5 mg of lorazepam orally two hours before surgery. Four hours after medication, each mother expressed a 10 mL sample of breast milk, and a sample of venous blood was taken for analysis of free lorazepam concentrations.

The results indicated low passage of the drug into breast milk. The free drug concentrations measured in the expressed milk (8 and 9 ng/ mL) were significantly lower than those reported in the newborn by McBride and colleagues (23 to 82 ng/mL) (93). No effects on the nursing infants were reported. In another study, lorazepam was detectable in breast milk, but the maximum amounts that an infant could absorb were reported to be pharmacologically insignificant (95).

Johnstone (105) conducted a study to assess the effect of maternal ingestion of lorazepam on neonatal feeding behavior. Mothers were given 5 mg of lorazepam orally one hour before labor was induced. Eighteen bottle-fed neonates of mothers in the experimental group were compared with 20 neonates in a control group whose mothers received no preinduction medication. Lorazepam had no significant effect on the volume of milk consumed or on the duration of the feeding process during the first 48 hours of life. The authors concluded that lorazepam had no detrimental effects on healthy term infants as judged by their feeding behavior. On this basis, neonatal exposure to lorazepam through breast-feeding does not seem to be associated with adverse effects on the infant.

Alprazolam

Risk to the fetus during pregnancy. Alprazolam, which was introduced in 1980, has replaced diazepam as the most widely prescribed benzodiazepine and is one of the drugs most often prescribed for anxiety to women of reproductive age. It is used in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (106,107). Alprazolam has a shorter half-life (ten to 24 hours) than other benzodiazepines, which results in less cumulative sedation when multiple daily doses are taken (107,108). Alprazolam, a triazolobenzodiazepine, and its two hydroxylated metabolites are known to cross the placenta (109,110).

In a prospective study conducted between 1982 and 1992, St. Clair and Schirmer (109) evaluated the pregnancy outcomes of 542 women who were exposed to alprazolam during the first trimester of pregnancy to monitor for early signals of potential drug-related risks to the fetus. They noted no pattern of defects and no excess of congenital anomalies or spontaneous abortions among 411 infants who were exposed to alprazolam during the first trimester.

Another study prospectively identified 236 women who were exposed to therapeutic dosages of alprazolam during the first trimester (111) and found associations with congenital malformations in five infants. These malformations included one unilateral cleft lip in an infant with a family history of clefts, one hypospadias, one congenital hip dislocation, one inguinal hernia, and one fused lacrimal duct. However, these data do not support an association between alprazolam and congenital defects.

Johnson and associates (88,89) described ten cases of major malformations among newborn infants who were exposed prenatally to alprazolam. One infant had a tracheoesophageal fistula, another had a tracheoesophageal fistula and a patent ductus arteriosus, four had bilateral inguinal hernia, one had unilateral inguinal hernia and cryptorchidism, one had strabismus that required surgery, and two had microcephaly.

By the end of 1986, the Upjohn pharmaceutical company had received 441 reports through its voluntary reporting system of exposure in utero during the first trimester of pregnancy to alprazolam or triazolam tablets, as described by Barry and St. Clair in 1987 (112). Most of the pregnant women stopped using these drugs when pregnancy was confirmed during the first trimester. About 24 patients continued to use alprazolam throughout their pregnancies. At the time of publication of the 1987 article, about a fifth of the 441 women were still awaiting the outcome of the pregnancy. One-sixth of the women had been lost to follow-up, and another one-sixth had had elective abortions for various reasons. There were 16 reports of spontaneous abortion or miscarriage for which no congenital anomaly was reported, two reports of stillbirth, and one neonatal death one day after birth. More than half of the women completed their pregnancies and delivered healthy children without complications.

Three cases have been reported of multiple congenital anomalies in newborns who were exposed in utero to alprazolam monotherapy or combination therapy (112). One report described Down's syndrome associated with maternal prenatal ingestion of a 5.5 mg dose of alprazolam and an unknown quantity of doxepin. Another report noted cat's eye with Pierre Robin syndrome in a newborn whose mother had ingested .5 mg of alprazolam daily for the first two months of pregnancy (112). The third report involved a mother who ingested either alprazolam or triazolam during the first trimester of pregnancy and delivered an infant with pyloric stenosis, moderate tongue-tie, umbilical hernia, ankle inversion, and clubfoot (112). No clear relationship was found between the use of alprazolam and the congenital malformations.

Vendittelli and colleagues (113) described a 28-year-old mother who had taken fluoxetine, .5 mg of alprazolam three times a day, four tablets each of vitamin B1 and B6 a day, and three heptaminol tablets a day for eight months, spanning a period before and after conception. This treatment was stopped at the end of the second month of pregnancy, when lipomeningocele was diagnosed. The pregnancy progressed normally, and the infant was delivered at term without complications. No family history of congenital birth defects was noted. Some cases of palatina defect associated with the use of benzodiazepines have also been described (113).

Two isolated cases of neonatal withdrawal syndrome in infants whose mothers took alprazolam throughout their pregnancy have been reported (112). In one case the mother took 3 mg a day, and a mild neonatal withdrawal syndrome developed when the infant was two days old. In the second case, the mother took 7 to 8 mg a day. By contrast, Shader (114) described a case in which no perinatal adverse effects were observed after the mother had been treated with alprazolam during pregnancy at an average dosage of 1.5 mg a day.

In summary, alprazolam is assumed to be capable of increasing the risk of congenital abnormalities when administered to pregnant women during the first trimester. Because the use of these drugs is rarely a matter of urgency, they should be avoided during the first trimester. Patients should be advised to communicate with their physicians about discontinuing alprazolam if they become pregnant during therapy or if they intend to become pregnant.

Risk to the infant during breast-feeding. Alprazolam is found in low concentrations in breast milk (115,116,117). However, no reports have been published on the use of alprazolam during breast-feeding. One case report described a lactating mother who was treated with .5 mg of alprazolam two or three times a day throughout her pregnancy and while she breast-fed. Breast-feeding was discontinued when the infant appeared restless and irritable at seven days. Withdrawal symptoms appeared in the infant within two or three days and were treated with phenobarbital elixir (117).

In a cohort study, mild drowsiness in a breast-feeding infant was reported in one of five cases in which breast-feeding mothers took alprazolam (118). This symptom resolved spontaneously despite continuation of therapy. Thus caution is indicated when alprazolam is prescribed to lactating mothers.

Discussion and conclusions

No benzodiazepines have been tested directly with pregnant and lactating women to determine the effects on the fetus, on the neonate, or on the nursing infant. At this point we do not have enough information about whether the potential benefits to the mother outweigh the risks to the fetus, and therefore the therapeutic value of a given drug must be weighed against theoretical adverse effects on the fetus before and after birth.

In view of the available literature, it appears to be safe to take diazepam during pregnancy. However, use of diazepam during lactation is not recommended because it has the potential to cause lethargy, sedation, and weight loss in infants. The use of chlordiazepoxide during both pregnancy and lactation seems to be safe. Few data are available to justify avoiding the use of clonazepam during pregnancy or lactation. No adverse effects have been reported with the use of lorazepam during lactation. However, it would be prudent to avoid alprazolam during both pregnancy and lactation.

As a general rule, exposure to any type of benzodiazepine during the first three months of pregnancy should be avoided, because the fetus is most vulnerable to toxic effects of drugs during this period of active organogenesis. However, use of medication during pregnancy is not absolutely contraindicated. To avoid the potential risk of congenital defects, physicians should use the benzodiazepines that have long safety records and should prescribe a benzodiazepine as monotherapy at the lowest effective dosage for the shortest possible duration. Also, high peak concentrations of the drugs should be avoided by dividing the daily dosage into at least two doses. Finally, the best means of monitoring the safety and efficacy of therapy should be determined.

For many anxiety disorders, nonpharmacological treatment—such as behavioral techniques, relaxation techniques, relaxation exercises, psychotherapy, and avoidance of caffeine—may be effective during pregnancy and lactation and should be attempted before pharmacologic management.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neurobiology in the School of Medicine of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Send correspondence to Dr. Iqbal at 1001 Sparks Research Center, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurobiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1720 Seventh Avenue South, Birmingham, Alabama 35294-0017 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Classifications, dosages, and effects of benzodiazepines during pregnancy and lactation

1. Bracken MB, Holford TR: Exposure to prescribed drugs in pregnancy and association with congenital malformations. Obstetrics and Gynecology 58:336-344, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

2. Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ: Use of benzodiazepines in anxiety disorders. New England Journal of Medicine 328:1398-1405, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kuhnz W, Nau H: Differences in in vitro binding of diazepam and N-desmethyldiazepam to maternal and fetal plasma proteins at birth: relation to free fatty acid concentration and other parameters. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 34:220-226, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mandelli M, Morselli PL, Nordio S, et al: Placental transfer of diazepam and its disposition in the newborn. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 17:564-572, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bakke OM, Haram K, Lygre T, et al: Comparison of the placental transfer of thiopental and diazepam in caesarian section. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 21:221-227, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Gillberg C: "Floppy infant syndrome" and maternal diazepam. Lancet 2:244, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Mazzi E: Possible neonatal diazepam withdrawal: a case report. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 129:586-587, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Cree JE, Meyer J, Hailey DM: Diazepam in labour: its metabolism and effect on the clinical condition and thermogenesis of the newborn. British Medical Journal 4:251-255, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Shannon RW, Fraser GP, Aitken RG, et al: Diazepam in preeclamptic toxemia with special reference to its effect on the newborn infant. British Journal of Clinical Practice 26:271-275, 1972Medline, Google Scholar

10. Van der Kleijn E: Protein binding and lipophilic nature of ataractics of the metrobamate and diazapime group. Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie 179:225-250, 1969Medline, Google Scholar

11. Anderson WAD: Pathology, 3rd ed. St Louis, Mosby, 1957Google Scholar

12. Allen MD, Greenblatt DJ: Comparative protein binding of diazepam and desmethyldiazepam. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 21:219-223, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Colburn WA, Gibaldi M: Plasma protein binding of diazepam after a single dose of sodium oleate. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 67:891-892, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Krasner J, Yaffe SJ: Drug-protein binding in the neonate, in Basic and Therapeutic Aspects of Perinatal Pharmacology. Edited by Morselli PL, Garattini S, Sereni F. New York, Raven, 1975Google Scholar

15. Erkkola R, Kanto J, Sellman R: Diazepam in early human pregnancy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 53:135-138, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kanto J, Erkkola R: The feto-maternal distribution of diazepam in early human pregnancy. Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae Fenniae 63:489-491, 1974Medline, Google Scholar

17. Erkkola R, Kangas L, Pekkarinen A: The transfer of diazepam across the placenta during labour. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 52:167-170, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Gamble JAS, Moore J, Lamki H, et al: A study of plasma diazepam levels in mother and infant. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 84:588-591, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kanto J, Erkkola R, Sellman R: Accumulation of diazepam and N-desmethyldiazepam in the fetal blood during labour. Annals of Clinical Research 5:375-379, 1973Medline, Google Scholar

20. Marcucci F, Fanelli R, Frova M, et al: Levels of diazepam in adipose tissue of rats, mice, and man. European Journal of Pharmacology 4:464-466, 1968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Idanpaan-Heikkila JE, Taska RJ, Allen HA, et al: Placental transfer of diazepam 14C in mice, hamsters, and monkeys. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 176:752-757, 1971Medline, Google Scholar

22. Aarskog D: Association between maternal intake of diazepam and oral clefts [letter]. Lancet 2:921, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Saxen I: Associations between oral clefts and drugs taken during pregnancy. International Journal of Epidemiology 4:37-44, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Safra MD, Oakley GP: Association between cleft lip with or without cleft palate and prenatal exposure to diazepam. Lancet 2:478-480, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Safra MJ, Oakley GP: An oral cleft teratogen? Cleft Palate Journal 13:198-200, 1976Google Scholar

26. Saxen I, Saxen L: Association between maternal intake of diazepam and oral clefts. Lancet 2:498, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Rosenberg L, Mitchell AA, Parsells JL, et al: Lack of relation of oral clefts to diazepam use during pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 309:1282-1285, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Entman SS, Vaughn WK: Lack of relation of oral clefts to diazepam use in pregnancy [letter]. New England Journal of Medicine 310:1121-1122, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

29. Czeizel A: Diazepam, phenytoin, and aetiology of cleft lip and/or cleft palate [letter]. Lancet 1:810, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Saxen I: Epidemiology of cleft lip and palate: an attempt to rule out chance correlations. British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine 29:103-110, 1975Medline, Google Scholar

31. Czeizel A, Lendvay A: In utero exposure to benzodiazepines [letter]. Lancet 1:628, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

32. Shino PH, Mills JL: Oral clefts and diazepam use during pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 311:919-920, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Czeizel A: Endpoints of reproductive dysfunction in an experimental epidemiological model: self-poisoned pregnant women, in New Concepts and Developments in Toxicology. Edited by Chambers PL, Gehring P, Sakai F. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 1986Google Scholar

34. Czeizel A, Pazsy A, Pusztai J, et al: Aetiological monitor of congenital abnormalities: a case-control surveillance system. Acta Paediatrica Hungarica 24:91-99, 1983Medline, Google Scholar

35. Gelenberg AJ (ed): Diazepam: not a teratogen? Massachusetts General Hospital Newsletter 7(2), 1984Google Scholar

36. Istavan EJ: Drug-associated congenital abnormalities? [letter] Canadian Medical Association Journal 103:1394, 1970Google Scholar

37. New Zealand Committee on Drug Reactions: Fourth annual report. New Zealand Medical Journal 70:118-122, 1969Medline, Google Scholar

38. Czeizel A, Szentesi I, Glauber A, et al: Pregnancy outcome and health condition of offspring of self-poisoned pregnant women. Acta Paediatrica Hungarica 25:209-236, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

39. Cerqueira MJ, Olle C, Bellart J, et al: Intoxication by benzodiazepines during pregnancy [letter]. Lancet 1:1341, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Rivas F, Hernandez A, Cantu JM: Acentric craniofacial cleft in a newborn female prenatally exposed to a high dose of diazepam. Teratology 30:179-180, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Laegreid L, Olegard R, Wahlstrom J, et al: Abnormalities in children exposed to benzodiazepines in utero. Lancet 1:108-109, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Olegard R, Sabel KG, Aronson M, et al: Effects on the child of alcoholic abuse during pregnancy. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica Supplement 275:112-121, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Gerhardsson M, Alfredsson L: In utero exposure to benzodiazepines [letter]. Lancet 1:628, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

44. Winter RM: In utero exposure to benzodiazepines [letter]. Lancet 1:627, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Laegreid L, Hagberg G, Lundberg A: The effect of benzodiazepines on the fetus and the newborn. Neuropediatrics 23:18-23, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Laegreid L, Hagberg G, Lundberg A: Neurodevelopment in late infancy after prenatal exposure to benzodiazepines: a prospective study. Neuropediatrics 23:60-67, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Rothman KJ, Fyler DC, Goldblatt A, et al: Exogenous hormones and other drug exposures of children with congenital heart disease. American Journal of Epidemiology 109:433-439, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Zierler S, Rothman KJ: Congenital heart disease in relation to maternal use of Bendectin and other drugs in early pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 313:347-352, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP: Risk factors for conal malformations of the heart. European Journal of Epidemiology 8:48-57, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Tikkanen J, Heinonen OP: Risk factors for ventricular septal defect in Finland. Public Health 105:99-112, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Scanlon JW: Effect of benzodiazepines in neonates [letter]. New England Journal of Medicine 292:649, 1975Medline, Google Scholar

52. Haram K: "Floppy infant syndrome" and maternal diazepam [letter]. Lancet 2:612-613, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Rementeria JL, Bhatt K: Withdrawal symptoms in neonates from intrauterine exposure to diazepine. Journal of Pediatrics 90:123-126, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Backes CR, Cordero L: Withdrawal symptoms in the neonate from presumptive intrauterine exposure to diazepam: report of case. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 79:584-585, 1980Medline, Google Scholar

55. Speight ANP: Floppy-infant syndrome and maternal diazepam and/or nitrazepam [letter]. Lancet 2:878, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Flowers CE, Rudolph AJ, Desmond MM: Diazepam (valium) as an adjunct in obstetric analgesia. Obstetrics and Gynecology 34:68-81, 1969Medline, Google Scholar

57. Speight ANP: Diazepam in pre-eclamptic toxemia. British Medical Journal 1:1420-1421, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

58. Woods DL, Malan AF: Side effects of maternal diazepam on the newborn infant [letter]. South African Medical Journal 54:636, 1978Medline, Google Scholar

59. Scher J, Hailey DM, Beard RW: The effects of diazepam on the fetus. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of the British Commonwealth 79:635-638, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Briger M, Homberg R, Insler V: Clinical evaluation of fetal movements. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 18:377-382, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Schiff D, Chan G, Stern L: Fixed drug combinations and the displacements of bilirubin from albumin. Pediatrics 8:139-141, 1971Google Scholar

62. Patrick MJ, Tilstone WJ, Reavey P: Diazepam and breast-feeding. Lancet 1:542-543, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Erkkola R, Kanto J: Diazepam and breast-feeding. Lancet 1:1235-1236, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Brandt R: Passage of diazepam and desmethyldiazepam into breast milk. Arzneimittelforschung 26:454-457, 1976Medline, Google Scholar

65. O'Brien TE: Excretion of drugs in human milk. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 31:844-845, 1974Medline, Google Scholar

66. Takyi BE: Excretion of drugs in human milk. American Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 38:317-326, 1970Google Scholar

67. Stirrat GM, Edington P, Berry DJ: Transplacental passage of chlordiazepoxide [letter]. British Medical Journal 2:729, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

68. Wesson DR, Camber S, Harkey M, et al: Diazepam and desmethyldiazepam in breast milk. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 17:55-56, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

69. Mark PM, Hamel J: Librium for patients in labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology 32:188-194, 1968Medline, Google Scholar

70. Pankaj V, Brain PF: Effects of prenatal exposure to benzodiazepine-related drugs on early development and adult social behavior in Swiss mice: I. agonists. General Pharmacology 22:33-41, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Milkovich L, Van den Berg BJ: Effects of prenatal meprobamate and chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride on human embryonic and fetal development. New England Journal of Medicine 291:1268-1271, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

72. Crombie DL, Pinsent RJ, Fleming DM, et al: Fetal effects of tranquilizers in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine 293:198-199, 1975Medline, Google Scholar

73. Kullander S, Kallen B: A prospective study of drugs and pregnancy: I. psychopharmaca. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica 55:25-33, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

74. Hartz SC, Heinonen OP, Shapiro S, et al: Antenatal exposure to meprobamate and chlordiazepoxide in relation to malformations, mental development, and childhood mortality. New England Journal of Medicine 292:726-728, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

75. Czeizel A: Lack of evidence of teratogenicity of benzodiazepine drugs in Hungary. Reproductive Toxicology 1:183-188, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

76. Decaneq Jr HG, Bosco JR, Townsend EH: Chlordiazepoxide in labor: its effect on the newborn infant. Journal of Pediatrics 67:836-840, 1965Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Bitnun S: Possible effects of chlordiazepoxide on the foetus. Canadian Medical Association Journal 100:351, 1969Medline, Google Scholar

78. Athinarayanan P, Peirog SH, Nigam SK, et al: Chlordiazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 124:212-213, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Catz CS, Giocoia GP: Drugs and breast milk. Pediatric Clinics of North America 19:151-166, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

80. Fisher JB, Edgren BE, Mammel MC, et al: Neonatal apnea associated with maternal clonazepam therapy: a case report. Obstetrics and Gynecology 66:34S-35S, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

81. Czeizel AE, Bod M, Halasz P: Evaluation of anticonvulsant drugs during pregnancy in a population-based Hungarian study. European Journal of Epidemiology 8:122-127, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

82. Haeusler MC, Hoellwarth ME, Holzer P: Paralytic ileus in a fetus-neonate after maternal intake of benzodiazepine. Prenatal Diagnosis 15:1165-1177, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Kriel RL, Cloyd J: Clonazepam and pregnancy [letter]. Annals of Neurology 11:544, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

84. Calabrese JR, Gulledge AD: Carbamazepine, clonazepam use during pregnancy [letter]. Psychosomatics 27:464, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

85. Eskazan E, Aslan S: Antiepileptic therapy and teratogenicity in Turkey. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology 30:261-264, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

86. Kaneko S, Koichi O, Yutaka F, et al: Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs: analysis of possible risk factor. Epilepsia 29:459-467, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

87. Dansky L, Andermann E, Sherwin AL, et al: Maternal epilepsy and congenital malformations: a prospective study with monitoring of plasma anticonvulsant levels during pregnancy [letter]. Neurology 3:15, 1980Google Scholar

88. Johnson KA, Jones KL, Chambers CD, et al: Pregnancy outcome in women exposed to non-valium benzodiazepines [letter]. Reproductive Toxicology 9:585, 1995Google Scholar

89. Johnson KA, Jones KL, Chambers CD, et al: Pregnancy outcome in women exposed to non-Valium benzodiazepines [letter]. Teratology 51:170, 1995Google Scholar

90. McElhatton PR: The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation. Reproductive Toxicology 8:461-475, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

91. Malone FD, D'Alton ME: Drugs in pregnancy: anticonvulsants. Seminars in Perinatology 21:114-123, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Gilles D, Lader M: Guide to the Use of Psychotropic Drugs. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 1986Google Scholar

93. McBride RJ, Dundee JW, Moore J, et al: A study of the plasma concentrations of lorazepam in mother and infant. British Journal of Anaesthesia 51:971-978, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

94. Kanto J, Aaltonen L, Linkka P, et al: Transfer of lorazepam and its conjugate across the human placenta. Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica 47:130-134, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Whitelaw AGL, Cummings AJ, McFadyen IR: Effect of maternal lorazepam on the neonate. British Medical Journal 282:1106-1108, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Athinarayanan P, Peirog SH, Nigam SK, et al: Chlordiazepoxide withdrawal in the neonate. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 124:212-213, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97. Godet PF, Damato T, Dalery J, et al: Benzodiazepines in pregnancy: analysis of 187 exposed infants drawn from a population-based birth defects registry. Reproductive Toxicology 9:585, 1995Google Scholar

98. Herd B, Clarke F: Complete heart block after flumazenil. Human and Experimental Toxicology 10:289, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

99. McAuley DM, O'Neill MP, Moore J, et al: Lorazepam premedication for labour. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 89:149-154, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

100. Sanchis A, Rosique D, Catala J: Adverse effects of maternal lorazepam on neonates. DICP Annals of Pharmacotherapy 25:1137-1138, 1991Google Scholar

101. Erkkola R, Kero P, Kanto J, et al: Severe abuse of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy with good perinatal outcome. Annals of Clinical Research 15:88-91, 1983Medline, Google Scholar

102. Majer RV, Green PJ: Neonatal afibrinogenaemia due to sodium valproate. Lancet 2:740-741, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

103. McEvoy GK (ed): AHFS Drug Information 1999. Bethesda, Md, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 1999Google Scholar

104. Summerfield RJ, Nielsen MS: Excretion of lorazepam into breast milk. British Journal of Anaesthesia 57:1042-1043, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

105. Johnstone MJ: The effect of lorazepam on neonatal feeding behavior at term. Pharmatherapeutica 3:259-262, 1982Medline, Google Scholar

106. Christensen HD, Gonzalez CL, Rayburn WF: Impact of prenatal alprazolam (Xanax N) on social play in inbred mice. Teratology 51:181-182, 1995Google Scholar

107. Gonzalez C, Smith R, Christensen HD, et al: Prenatal alprazolam induces subtle impairments in hind limb balance and dexterity in C57BL/6 mice [abstract]. Teratology 49:390, 1994Google Scholar

108. Garzone PD, Kroboth PD: Pharmacokinetics of the newer benzodiazepines. Clinical Pharmacokinetics 16:337-364, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

109. St Clair SM, Schirmer RG: First trimester exposure to alprazolam. Obstetrics and Gynecology 80:843-846, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

110. Ornay A, Arnon J, Shechtman S, et al: Is benzodiazepine use during pregnancy really teratogenic? Reproductive Toxicology 12:511-515, 1998Google Scholar

111. Schick-Boschetto B, Zuber C: Alprazolam exposure during early human pregnancy [abstract]. Teratology 45:460, 1992Google Scholar

112. Barry WS, St Clair SM: Exposure to benzodiazepines in utero. Lancet 1:1436-1437, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

113. Vendittelli F, Alain J, Nouaille Y, et al: A case of lipomeningocele reported with fluoxetine (and alprazolam, vitamins B1 and B6, heptaminol) prescribed during pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology 58:85-86, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

114. Shader RI: Is there anything new on the use of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy? Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 14:438, 1994Google Scholar

115. Oo CY, Stowe C, Kuhn R, et al: Alprazolam transfer into human milk: in vivo evaluation of a diffusional model. Pharmaceutical Research 10(suppl):S348, 1993Google Scholar

116. Oo CY, Kuhn RJ, Desai N, et al: Pharmacokinetics in lactating women: prediction of alprazolam transfer into milk. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 40:231-236, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

117. Anderson PO, McGuire GG: Neonatal alprazolam withdrawal: possible effects of breast feeding [letter]. DICP Annals of Pharmacotherapy 23:614, 1989Google Scholar

118. Ito S, Blajchman A, Stephenson M, et al: Prospective follow-up of adverse reactions in breastfed infants exposed to maternal medication. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 168:1393-1399, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar