Outcomes of a Cognitive-Behavioral Day Treatment Program for a Heterogeneous Patient Group

Abstract

This paper describes a day treatment program that provides predominantly cognitive-behavioral therapy for a heterogeneous group of patients. Preliminary results of the program are also presented. Assessment tools included the Beck Depression Inventory, the Symptom Checklist, and a questionnaire on changes in social life. Instruments were administered at admission, at discharge, and six months after discharge. The patients showed significant improvement in scores on all instruments at discharge. Improvements were stable after six months for all diagnostic categories—depression, eating disorders, and personality disorders. The program shows promise as an effective treatment approach for patients with various psychiatric diagnoses.

In 1996 the inpatient treatment program of University Psychiatric Services in Bern, Switzerland, was transformed into a day treatment program to improve the transfer and generalization of behavioral skills to daily life and to reduce costs. In contrast with most other programs with published outcomes data, the Bern day treatment program provides predominantly cognitive-behavioral therapy to patients with heterogeneous diagnoses. This approach differs from those used by most day treatment programs described in the literature, which emphasize either a psychodynamic approach (1,2,3) with little attention to specific manual-guided strategies or a cognitive-behavioral approach that is specialized for specific diagnoses (4,5,6).

In this paper we describe our program and present the first outcomes data. We evaluated our program among different diagnostic groups in terms of its effects on depression, psychopathology, and psychosocial functioning. We also tested whether improvements endure beyond discharge from the program.

Methods

The cognitive-behavioral day treatment program is offered to 14 patients at a time. The duration of treatment is 12 to 20 weeks, divided into three phases: the diagnostic phase, which lasts for three weeks; the treatment phase, which is six to 14 weeks long; and the rehabilitation phase, which takes up the last three weeks of treatment. The treatment is coordinated during two-hour weekly team meetings and brief daily team meetings. Individual 50-minute cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions are held twice weekly.

Specific groups were established on the basis of published manuals and include groups for assertiveness training and dialectical behavior therapy skills training as well as groups covering eating disorders. Large groups, which involve all patients, include a morning group, a recreational group, and a goal-attainment group. Groups that focus on nonverbal expression, body awareness, and gender-related topics supplement the program.

The admission criteria were major deterioration in outpatient treatment or need for day treatment after or instead of inpatient treatment. Patients exhibiting psychotic disorders and primary substance abuse were excluded from the program. Three weeks after entering the program, all patients received diagnoses based on ICD-10 categories.

To measure depression and general psychopathology, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (7) and the Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) (8) were administered at admission, at discharge, and six months after discharge. Possible scores on the BDI range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptoms, and possible scores on the SCL-90-R range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more psycopathology. Both instruments are well established. We used the total score on the BDI and the general symptom index from the SCL-90-R for the analyses.

To measure psychosocial changes, a questionnaire on changes in social life (9) was administered at discharge and six months after discharge. With this unpublished instrument, respondents rate changes in their satisfaction with life since the beginning of the program on a scale of -4 to 4, with negative scores indicating deterioration and positive scores indicating improvement. The questionnaire includes 11 items: relationship with family members in general, relationship with father, relationship with mother, relationship with partner, relationship with own children, other close relationships, contact and relations in general, work, recreation, mood, and future expectations. The mean score of all answers was used for the analyses.

Results

A total of 121 patients were admitted to the day treatment program between March 1996 and October 1999. Thirty-two patients had been discharged too recently to have completed the six-month follow-up and were therefore excluded from the analyses. Fifty-five, or 61.8 percent, of the remaining 89 patients were eligible for inclusion in the analyses. Twenty-four patients, or 19.8 percent, dropped out. Data were incomplete for ten patients.

The mean±SD age of the 121 patients was 28.7±7.5 years. Ninety-three patients, or 76.9 percent, were single, and 30 patients, or 24.8 percent, had a current job. Patients were predominantly referred by psychiatric inpatient units (45 patients, or 37.2 percent), their psychiatrist or psychologist (36 patients, or 29.8 percent), or an outpatient unit (27 patients, or 22.3 percent).

The frequencies of the main diagnoses, including comorbidities, were as follows: 71 patients, or 58.7 percent, had depression, including depressive episodes and adjustment disorders; 59 patients, or 48.8 percent, had eating disorders; and 40 patients, or 33.1 percent, had personality disorders. Fifty patients, or 41.3 percent, had a duration of illness exceeding five years, and 72 patients, or 59.5 percent, had had at least one psychiatric inpatient treatment. During the study, antidepressant medication was given to 67 patients, or 60.9 percent of the total sample. The participants' mean±SD duration of treatment was 104±42.3 days. There were no significant differences in any of the sociodemographic or admission variables between the 55 patients who were eligible for inclusion in the analyses and the total sample of 121 patients.

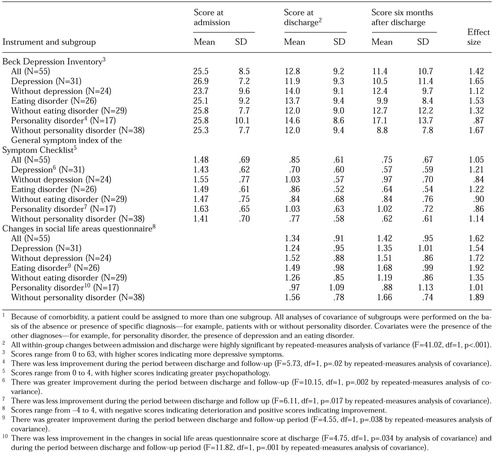

As a group, the 55 patients showed highly significant improvements on the BDI, the SCL-90-R, and the questionnaire on changes in social life between admission and discharge (Table 1). No significant additional changes were observed at follow-up.

Analyses of diagnostic subgroups were conducted as well. Because of comorbidity, a patient could be assigned to more than one subgroup. Patients with depression had a higher rate of improvement in symptoms between discharge and follow-up than patients without depression, as measured by the general symptom index of the SCL-90-R (F=10.15, df=1, p<.02). Patients with eating disorders reported higher psychosocial satisfaction on the social life questionnaire between discharge and follow-up (F=4.55, df=1, p<.002). Patients with a personality disorder showed less improvement on the social life questionnaire between admission and discharge than patients without a personality disorder (F=4.75, df=1, p=.034). Between discharge and follow-up, patients with a personality disorder improved less on all questionnaires, notably on the questionnaire on changes in social life (F=11.82, df=1, p=.001) but also on the BDI (F=5.73, df=1, p=.02) and the SCL-90-R (F=6.11, df=1, p= .017). However, the mean effect size for patients with a personality disorder was still .91.

Discussion and conclusions

On the whole, our data suggest that the day treatment program is effective for a patient group with a variety of diagnoses and that this result endures beyond discharge. The changes in questionnaire scores indicate a clinically significant improvement. Given the findings reported in the literature, we expected to find the smallest improvements for patients with personality disorders. Thus our results were consistent with those of previous studies that showed the worst outcomes for these patients.

The fact that improvements in scores on the questionnaire on changes in social life were minor may have been a result of severe interpersonal problems, which are common in patients with personality disorders (10). Nevertheless, the mean effect size of .91 in this subgroup six months after discharge is high and seems to be on par with outcomes found in specialized units (2,3). Our data suggest that an outpatient follow-up program would be useful for patients with personality disorders. This finding is consistent with those of other authors (1,2,3) who have emphasized the need for longer programs for patients with such disorders.

Our study had several limitations. Not all patients who were admitted to our program could be included in the analyses. We used clinical diagnoses rather than structured diagnostic interviews. In addition, this was a naturalistic study, so spontaneous remission or medication effects cannot be ruled out.

The challenge of a day treatment program that provides predominantly cognitive-behavioral therapy for a heterogeneous patient group is to supply diagnosis-specific therapies to all patients. The data we have presented suggest that our program is effective and that it can serve as a useful model for psychiatric services in small communities.

Dr. Reisch and Dr. Thommen are affiliated with the psychotherapy day treatment program and Dr. Tschacher and Dr. Hirsbrunner are affiliated with the research division of the department of social and community psychiatry at the University of Bern in Switzerland. Send correspondence to Dr. Reisch at the University Hospital of Social and Community Psychiatry, Murtenstrasse 21, 3010 Bern, Switzerland (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, the Symptom Checklist, and a questionnaire on changes in social life along with effect size from admission to discharge for patients with various diagnoses who were treated in the Bern day treatment program1

1. Piper WE, Joyce AS, Azim HFA, et al: Patient characteristics and success in day treatment. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders 182:381-386, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bateman A: Effectiveness of partial hospitalization in the treatment of borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1563-1569, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Wilberg T, Urnes O, Friis S, et al: One-year follow-up of day treatment for poorly functioning patients with personality disorder. Psychiatric Services 50:1326-1330, 1999Link, Google Scholar

4. Bystritsky A, Saxena S, Maidment K, et al: Quality-of-life changes among patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder in a partial hospitalization program. Psychiatric Services 50:412-414, 1999Link, Google Scholar

5. Gerlinghoff M, Backmund H, Franzen U, et al: Structured day care therapy program for eating disorders [in German]. Psychotherapie, Psychomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 47:12-20, 1997Google Scholar

6. Simpson EB, Pistorello J, Begin A, et al: Use of dialectical behavior therapy in a partial hospital program for women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatric Services 49:669-673, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Beck A: The Beck Depression Inventory: A Textbook [in German]. Bern, Switlerland, Huber, 1994Google Scholar

8. Franke G: SCL-90-R: The Symptom Checklist [in German]. Weinheim, Germany, Beltz, 1994Google Scholar

9. Grawe K: Change in Social Life Areas (VLB) [in German]. Unpublished questionnaire. Bern, Switzerland, Department of Psychology, University of Bern, 1992Google Scholar

10. Fiedler P: Personality Disorders [in German]. Weinheim, Germany, Beltz, 1994Google Scholar