Pilot Study of the Effectiveness of the Family-to-Family Education Program

Abstract

This study assessed the efficacy of the Family-to-Family Education Program, a structured 12-week program developed by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. A total of 37 family members who participated in the program were evaluated by an independent research team of trained family member assessors at baseline, after completing the program, and six months after program completion. After completing the program, the participants demonstrated significantly greater family, community, and service system empowerment and reduced displeasure and worry about the family member who had a mental illness. These benefits were sustained at six months.

In recent years, algorithms and best-practice guidelines have been developed to guide the provision of educational and support services to families of persons with schizophrenia. Research on the efficacy of family psychoeducation provides the empirical base for these algorithms and guidelines. However, most families do not receive services that are consistent with best-practice standards (1). The dearth of such services in the mental health system has led to the development of family education programs.

Although family education shares many of the goals and strategies of family psychoeducation, such as providing education and support and helping family members cope more effectively with the person who has a mental illness, there are significant differences between the two types of intervention (2,3). Psychoeducation tends to be clinic based and delivered by health care professionals, whereas family education can be community based and delivered by trained family members. Family education is usually shorter in duration than family psychoeducation, and it is not linked to the treatment being received by the family member who has a mental illness.

The two interventions also have different conceptual underpinnings: psychoeducation derives from theories of expressed emotion, whereas family education is based on theories of stress, coping, and adaptation. The primary outcome of concern in family education is the well-being of the family; psychoeducation primarily tends to consider patient outcomes. Finally, family psychoeducation programs are generally diagnosis specific, whereas family education is used with a variety of patient diagnoses (3).

The most widely used family education model is the Family-to-Family Education Program (formerly the Journey of Hope Education Program), developed in the early 1990s by one of the authors (J.B.) and sponsored by the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. This 12-week program is taught by trained family member volunteers with the use of a highly structured, scripted manual (4). In weekly two- to three-hour sessions, family caregivers receive information about mental illnesses, treatments and medication, and rehabilitation. They learn self-care and communication skills as well as problem-solving and advocacy strategies.

The use of the Family-to-Family Education Program is widespread (5), and it appears to be very popular with its attendees. Isolated studies have found that family members who participate in family education programs have greater knowledge and self-efficacy and are more satisfied with the patient's treatment than those who do not (6,7). However, research on the Family-to-Family Education Program is limited, and no systematic evaluation of its effectiveness has been conducted.

The study reported here was a prospective, longitudinal evaluation of the Family-to-Family Education Program. We hypothesized that program participants would have improved well-being, empowerment, self-esteem, and mastery and would experience a reduced subjective burden of mental illness.

Methods

A total of 37 consenting family members were drawn from five Family-to-Family Education Program classes that were scheduled to begin in the fall of 1998 in the greater Baltimore metropolitan area. All the classes were conducted by teachers who were trained by the program's originator and director in accordance with the program manual. Thirty-one (84 percent) of the participants were women; 30 (81 percent) were Caucasian, and seven (19 percent) were African American; and 21 (57 percent) were parents. The participants' mean±SD age was 55±11.72 years, and they had a mean±SD of 14.9± 1.85 years of education. Overall, the family members were caring for 37 persons who had a mental illness. The mean age of those receiving care was 33±14.92 years, and their mean number of previous hospitalizations was 3.2±1.11. Twenty-one (57 percent) were men.

Study participants were assessed prospectively at baseline, immediately after completion of the program, and six months after program completion. The participants' subjective burden—for example, worry, displeasure, and subjective global displeasure—and objective burden—for example, assistance with daily living and supervision—of mental illness as well as their attitudes toward professionals were measured by use of subscales of the Family Experience Interview Schedule (8). Indexes of self-esteem, sense of mastery, social network, depression, and physical health were derived from the Family Impact Study (9). Empowerment was measured with the Family Empowerment Scale (10). The tests were administered by trained family member interviewers during 35- to 45-minute telephone calls to the participants. The calls were monitored for reliability.

We conducted paired t tests (one-tailed) to compare baseline assessments with completion assessments. To determine whether gains observed at completion were sustained after six months, we conducted paired t tests (two-tailed) between assessments at completion and at six-month follow-up. We applied a Bonferroni correction to minimize the possibility of type I error and required a p value of .004 or less.

Results

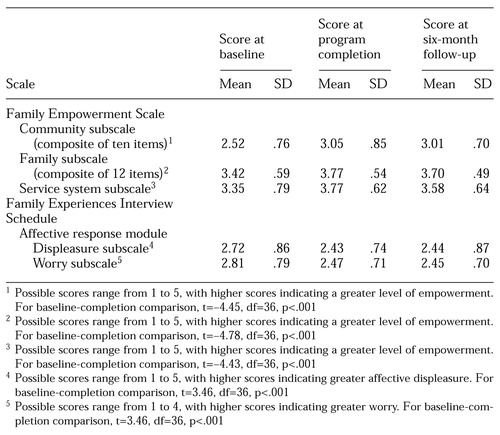

Assessments at program completion indicated that the participants felt significantly more empowerment in the community, in their family, and with the service system than they did at baseline; they also experienced less displeasure and worry about their ill family member (Table 1). No differences were noted in measures of objective family burden, attitudes toward professionals, self-esteem, sense of mastery, depression, social network, and physical health. No significant improvements or deteriorations were noted for any measure between program completion and the six-month follow-up.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study suggest that the Family-to-Family Education Program enhanced family members' empowerment and reduced their subjective burden of mental illness by diminishing worry and displeasure. These benefits were evident by the end of the 12-week program, and they were sustained for six months after program completion. Given that the program is widely used and has received considerable financial support from state governments (5), this initial test of efficacy is important.

Completing the program did not appear to affect the participants' objective burden of mental illness, that is, the actual, tangible "work" that they do to care for their ill family member, nor did it affect their self-esteem or sense of mastery. The intervention may have been too brief to have had an impact on these domains, or perhaps our measures were not sensitive enough to detect any changes.

Although this study focused on the impact of the Family-to-Family Education Program on family member participants, the results could have implications for improving patient outcomes. Reduced worry and displeasure might allow program participants to provide a less tense and stimulating family environment for the patient. Improvements in family members' empowerment could enhance their ability to advocate for better care, which in turn could result in more appropriate treatment for patients. However, the program's implications for patients have not been empirically evaluated.

It should be noted that the study was limited by its small size and scope and the lack of a control group. Nonetheless, the results are encouraging with respect to the efficacy of the program.

Dr. Dixon is associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and associate director of research at the Department of Veterans Affairs Capital Health Care Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center in Baltimore. Ms. Stewart, Ms. Delahanty, Dr. Lucksted,and Ms. Hoffman are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Services Research at the University of Maryland. Dr. Burland is deputy executive director of the education and training department at the National Association for the Mentally Ill in Arlington, Virginia. Address correspondence to Dr. Dixon, University of Maryland, Department of Psychiatry, 701 West Pratt Street, Room 476, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Scores on the subscales of the Family Empowerment Scale and the Family Experiences Interview Schedule of 37 family members who participated in the Family-to-Family Education Program

1. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Burland J: Family-to-family: a trauma and recovery model of family education. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 77:33-44, 1998Google Scholar

3. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364-1370, 1996Link, Google Scholar

4. Burland J: Family-to-Family Education Course. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1998Google Scholar

5. Dixon L, Goldman HH, Hirad A: State policy and funding of services to families of adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:551-552, 1999Link, Google Scholar

6. Solomon P, Draine J, Mannion E, et al: Effectiveness of two models of brief family education: retention of gains by family members of adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:177-186, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Pickett SA, Cook JA, Laris A: The Journey of Hope: Final Evaluation Report. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, 1997Google Scholar

8. Tessler RT, Gamache G: Toolkit for evaluating family experiences with severe mental illness. Cambridge, Mass, Health Services Research Institute Evaluation CenterGoogle Scholar

9. Struening EL, Stueve A, Vine P, et al: Factors associated with grief and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with mental illness. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:91-124, 1995Google Scholar

10. Koren PE, DeChillo N, Friesen BJ: Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology 37:305-321, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar