Trauma, Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Associated Problems Among Incarcerated Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To help improve treatment for incarcerated veterans, the study examined exposure to trauma, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), functional status, and treatment history in a group of incarcerated veterans. METHODS: A convenience sample of 129 jailed veterans who agreed to receive outreach contact completed the Life Event History Questionnaire, the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C), and the Addiction Severity Index. Participants who had scores of 50 or above on the PCL-C, designated as screening positive for PTSD, were compared with those whose scores were below 50, designated as screening negative for PTSD. RESULTS: Some 112 veterans (87 percent) reported traumatic experiences. A total of 51 veterans (39 percent) screened positive for PTSD, and 78 veterans (60 percent) screened negative. Compared with veterans who screened negative for PTSD, those who screened positive reported a greater variety of traumas; more serious current legal problems; a higher lifetime use of alcohol, cocaine, and heroin; higher recent expenditures on drugs; more psychiatric symptoms; and worse general health despite more previous psychiatric and medical treatment as well as treatment for substance abuse. CONCLUSIONS: The findings encourage the development of an improved treatment model to keep jailed veterans with PTSD from repeated incarceration.

The number of incarcerated persons in the United States is growing, and a substantial proportion of these individuals have psychiatric disorders (1). Attempts to recognize and address these disorders would likely decrease recidivism and the duration of incarceration (2,3). Among disorders that may be present in incarcerated individuals, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has recently gained some attention. The prevalence of PTSD has been examined among incarcerated women (4,5), incarcerated male adolescents (6,7), and incarcerated men (8). These studies uniformly found higher rates of PTSD in their samples than in the general population.

Symptoms of psychological trauma have not been systematically evaluated in jailed veterans. However, the number of incarcerated veterans is increasing despite declines in the national population of veterans (9). Also, documented demographic differences between veteran and nonveteran inmates (9) argue for specific evaluation of incarcerated veterans.

Substance use disorders are also highly prevalent in incarcerated populations (10,11). Such disorders and PTSD often co-occur (12,13). It seems plausible that the interplay between PTSD and substance use contributes to the involvement of some individuals in the criminal justice system. Our study sought to address this question by evaluating how symptoms of PTSD were related to various types of traumatic experiences in a sample of jailed veterans and to their substance use, legal history, functional status, and treatment history. We hypothesized that symptoms of PTSD and substance use problems would be highly prevalent among incarcerated veterans and would be associated with impaired psychosocial adjustment (14).

In previous studies with incarcerated and general population samples, the prevalence of PTSD varied as a function of the type of trauma (8,13,15). Our study afforded the first opportunity to look at the relationship between types of trauma and symptoms of PTSD in a population of incarcerated veterans.

Incarcerated veterans with PTSD may constitute part of a large pool of underserved veterans with PTSD (16) who might benefit from more involvement in treatment. However, the type and intensity of treatment should be guided by the response to previous treatment. Because treatment histories of incarcerated veterans have not been described before, our study offers some direction in this regard.

Methods

The study was conducted between April 1998 and June 1999. The 129 participants in this study came from a convenience sample of veterans who were incarcerated in the King County Jail system in Seattle and King County, Washington, and who agreed to be interviewed as a routine part of a clinical outreach program. Although participation in the outreach program relied solely on self-report of veteran status, the veteran status of 112 (87 percent) of the participants was confirmed by prior or subsequent eligibility determinations by the Department of Veterans Affairs. The participants completed two self-report measures—the Life Event History Questionnaire (13) and the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version for DSM-IV (PCL-C) (17,18,19,20)—and a structured interview, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (21).

The Life Event History Questionnaire asks respondents to identify any lifetime experience of 11 life-threatening or traumatizing events that qualify as traumas for a DSM-III-R diagnosis of PTSD. A 12th item is an open-ended question about "other" terrible experiences that most people never go through and may be coded as either qualifying or not qualifying as a traumatic stressor according to criterion A of DSM-IV. The utility of the Life Event History Questionnaire in assessing traumatic exposure has been demonstrated in civilian populations (13).

The ASI is designed to assess individuals with substance use problems and captures demographic information as well as information about seven domains in which these individuals may develop difficulties: medical, employment, alcohol, drugs, family or social, legal, and psychiatric. Composite scores can be calculated for each domain. The composite scores range from 0 to 1 and provide a numerical estimate of an individual's current functioning in each domain, with 0 indicating no problem whatsoever and 1 indicating the most severe problem possible (22). Because it taps a variety of domains, in addition to an assessment for substance abuse, the ASI also furnishes information about previous treatment and functional status.

With the PCL-C, respondents rate the extent to which they are bothered by 17 different symptoms—corresponding to the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD—that people may have in response to stressful life events. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents not at all bothered and 5 represents extremely bothered. Possible scores thus range from 17 to 85, with higher scores indicating a greater likelihood of PTSD. The instrument has good test-retest reliability and internal consistency (17). Convergent validity is supported by high correlations with the Mississippi Scale for PTSD (17).

The participants were divided into two groups: those who had scores of 50 or above on the PCL-C—designated as screening positive for PTSD—and those who had scores of below 50—designated as screening negative. Previous studies concluded that a cutoff score between 42 and 50 on the PCL-C could be used to indicate a likelihood of PTSD (17,18,19,20). Although some previous research suggests that a cutoff score on the PCL-C in the range of 42 to 44 offers more diagnostic efficiency (17,19), those results were obtained in samples that were demographically different from ours, so we chose the more conservative cutoff of 50. A cutoff score of 50 on the PCL-C provides good diagnostic sensitivity (.82) and specificity (.83), with a kappa coefficient of .64 (17).

The two groups—veterans who screened positive and those who screened negative for PTSD—were compared with use of the chi square statistic, with continuity correction, for categorical variables. Because most continuous variables that were assessed in this study exhibited nonnormal distributions, the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables between groups.

Results

A total of 124 participants (96 percent) were male, 77 (60 percent) were white, 41 (32 percent) were African American, six (5 percent) were Native American, three (2 percent) were Hispanic, and two (2 percent) were Asian American. The mean±SD age of the veterans was 43.3±9.2 years. Only 14 veterans (11 percent) had less than a high school education. A total of 61 (47 percent) had 12 years of education, and 54 (42 percent) had more than 12 years. Before incarceration, 61 participants (47 percent) held regular employment. Of 115 veterans for whom data on marital status were available, 28 (24 percent) were never married, 14 (12 percent) were married, 71 (62 percent) were separated or divorced, and two (2 percent) were widowed. Homelessness over the previous three years was reported by 28 veterans (22 percent). The veterans had been incarcerated for an average of 20.53±9.56 days before the interview.

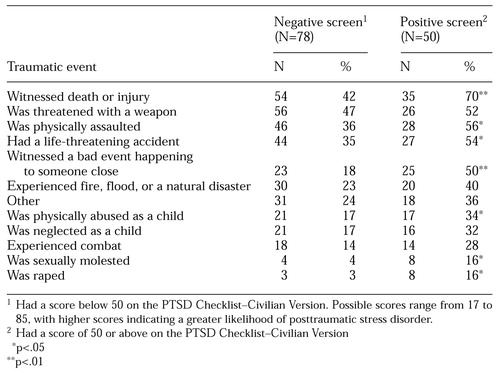

Of the 128 participants who completed the Life Event History Questionnaire, 112 (87 percent) reported at least one lifetime traumatic event. The mean±SD number of events reported was 2.8±2.1. The number of traumatic events did not vary significantly as a function of race or ethnicity (data not shown). Table 1 shows the frequencies of various traumatic experiences among the veterans in our sample.

The mean±SD score on the PCL-C was 44±18. Fifty-one participants, or 39 percent, had scores of 50 or above, thus screening positive for PTSD. No participants who reported no lifetime traumatic events on the Assessment of Life Stress had scores of 50 or above on the PCL-C, a finding that supports the internal validity of the screening approach in this sample. Our approach was further supported by a strong association between the number of reported lifetime traumatic events and the total PCL-C score (r=.58, df=127, p<.001).

Participants who screened positive for PTSD reported significantly more total lifetime traumas (3.92±1.86, mean rank, 84.16) than those who screened negative (2.15±1.88, mean rank, 51.9) (Mann-Whitney U=967, p<.001). As shown in Table 1, the groups differed in their reporting of some specific traumatic events. The items that assessed vicarious trauma— "witnessed death or injury" and "witnessed a bad event happening to someone close"—were most strongly associated with screening positive for PTSD. Participants who reported a history of childhood trauma were more likely than those who denied childhood trauma to screen positive for PTSD: of 40 veterans who reported childhood trauma, 22, or 55 percent, screened positive for PTSD; of 88 veterans who denied childhood trauma, only 28, or 32 percent, screened positive for PTSD (χ2=5.27, df=1, p<.03).

The veterans who screened positive for PTSD did not differ significantly from those who screened negative in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, or educational level. Only 16 of the veterans who screened positive for PTSD, or 31 percent, had been regularly employed over the previous three years, compared with 45 participants who screened negative, or 58 percent (χ2=7.5, df=1, p=.007).

In terms of involvement with the criminal justice system, this sample tended to be highly recidivist. The mean±SD number of total lifetime legal charges was 10.45±14.84 (median, 5.5); of total lifetime convictions, 5.8±8.44 (median, 3); and of lifetime months of incarceration, 20.7±25.76 (median, 10). Veterans who screened positive for PTSD consistently had higher rates of legal involvement than those who screened negative, but these differences were not statistically significant. Veterans who screened positive did have more severe overall current legal problems, as indicated by higher ASI legal composite scores: a mean±SD score of .326±.148 (mean rank, 75.93), compared with .260± .144 (mean rank, 57.85) for veterans who screened negative (U=1,431.5, p=.007).

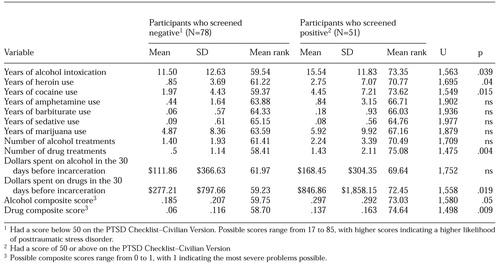

Table 2 conveys data on lifetime use of various substances by the participants, the number of lifetime substance abuse treatment episodes, and recent expenditures on substances. Veterans who screened positive for PTSD had greater lifetime use of alcohol to the point of intoxication, of heroin, and of cocaine but did not differ significantly from veterans who screened negative in lifetime use of other substances. Previous treatment for alcohol and drug problems was common; veterans who screened positive for PTSD reported higher rates of drug treatment. Participants spent substantial sums on substances immediately before incarceration. Veterans who screened positive for PTSD spent more on drugs, had slightly higher ASI alcohol composite scores, and had considerably higher ASI drug composite scores.

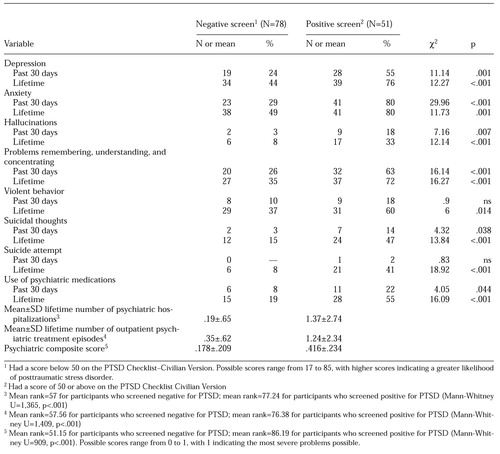

Table 3 contains information on the veterans' psychiatric symptoms and treatment. The entire sample reported extensive symptoms, but veterans who screened positive for PTSD reported much higher rates of psychopathology. Particularly striking, and consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD, is the difference between groups in anxiety during the 30 days before the interview. Participants who screened positive for PTSD also had more lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations and outpatient psychiatric treatment than those who screened negative. Note that despite high rates of psychiatric symptoms and previous psychiatric treatment, only a minority of participants who screened positive for PTSD received treatment with psychiatric medications in the 30 days before the interview (Table 3). In addition, participants who screened positive had much higher ASI psychiatric composite scores.

Veterans who screened positive for PTSD described worse general physical health than those who screened negative. These veterans had a mean± SD lifetime number of hospitalizations for medical problems of 2.9± 4.11 (mean rank, 72.87), compared with 1.65±2.09 (mean rank, 59.85) for veterans who screened negative for PTSD (U=1587.5, p<.05). They were also more likely to have a chronic medical problem that interfered with their lives: 31 veterans who screened positive for PTSD, or 61 percent, reported such a problem, compared with 25 veterans who screened negative, or 32 percent (χ2=8.88, df=1, p=.003). Veterans who screened positive were also more likely to have been bothered by medical problems in the previous 30 days, reporting 9.49±13.39 such days (mean rank, 72.11), compared with 4.60±10.18 days (mean rank, 60.35) for veterans who screened negative (U=1,626.5, p<.04).

Discussion and conclusions

This study showed that trauma exposure and symptoms of PTSD are prevalent among incarcerated veterans. The individuals in our study reported a variety of psychologically traumatic events. In addition to their involvement with the criminal justice system, they had a multitude of difficulties that indicated serious functional impairment, including substance abuse, psychiatric problems, and medical problems. These observations are consistent with earlier evaluations of PTSD in incarcerated populations (4,5,6,7,8) and extend those findings on the basis of a standardized interview—the ASI—that addresses multiple functional domains and obtains reports of previous treatment involvement.

The rate of positive PTSD screenings observed among jailed veterans in this study (39 percent) was much higher than the lifetime PTSD rate of 7.8 percent reported in the general population (13). However, the positive screening rates we observed are commensurate with rates observed in other incarcerated populations (4,5,7,8).

Exposure to combat was the trauma most likely to lead to PTSD among males in a general population survey of 5,877 individuals (13). However, in a community survey of 2,181 individuals, the association between combat experience and PTSD was very low, perhaps because of the low prevalence of combat exposure in that sample (15). The rate of exposure to combat in our sample was 19 percent, which is similar to the rates of 20 percent to 21 percent found in another evaluation of incarcerated veterans (9). However, exposure to combat was not the trauma most closely associated with screening positive for PTSD in our study.

In a previous examination of PTSD among incarcerated men (8), witnessing someone being badly injured or killed was the traumatic event that most frequently resulted in PTSD. Of the 213 individuals in that study, only 34 percent were veterans, of whom only 9 percent were exposed to combat. Witnessing served as the second most common event leading to PTSD for males in one general population sample (13), although it was a less common cause in another survey (15). The reason witnessing an event is the most common trauma associated with PTSD in criminal justice populations remains elusive. However, this finding encourages the speculation that violence occurring in these individuals' environments may be quite disturbing.

The connection between substance abuse problems and PTSD has been reported in community and clinical samples (13,23). The results of our study suggest that the association is also present among jailed veterans. Although the total sample included many veterans with long histories of substance abuse and treatment for substance abuse problems, the degree of alcohol, heroin, and cocaine use was greater among veterans who screened positive for PTSD, even though these veterans had had considerably more episodes of drug treatment. These results are consistent with earlier findings that combat veterans with PTSD were likely to have worse substance abuse problems than veterans without PTSD (23).

The most recent thinking about the association between PTSD and substance abuse suggests that for combat veterans (24) and civilians (12), the onset of PTSD typically precedes the onset of substance use disorders. Although we did not attempt to elicit specific information on chronology, participants who had experienced traumatic events in childhood were more likely to screen positive for PTSD. This finding lends additional modest support to the notion that trauma and PTSD typically precede substance use problems.

As with substance use disorders, the co-occurrence of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders has been commonly observed in community samples (13) and in treatment-seeking (25) and incarcerated (4,8) populations. Although we did not obtain categoric, clinical psychiatric diagnoses, the results of our study suggest that jailed veterans who screened positive for PTSD experience more severe psychopathology than those who screen negative.

The results of this study also suggest that jailed veterans who screen positive for PTSD are likely to have more disturbances in general health than those who screen negative and to have undergone more hospitalizations for such problems. Again, these findings corroborate the results of previous studies that showed that the presence of PTSD has an adverse impact on general health status (26).

Our data do have limitations. First, the study used a convenience sample rather than a random sample. It is possible that veterans with symptoms of trauma were more likely to volunteer to be evaluated. Because the sample included only military veterans, our findings, although analogous to data obtained in other incarcerated samples, may not be generalizable to all incarcerated populations. Information on the military experiences of these veterans was not collected but might have offered additional insight into the veterans' trauma symptoms.

Also, PTSD screening was based on a self-report measure rather than a clinical diagnostic interview. Although the ASI is a structured interview, the accuracy of most of the information it elicits depends on the patient's truthfulness.

Finally, multiple comparisons between groups were conducted. With this number of comparisons, it is possible that some significant differences occurred by chance alone. Rather than correct for such a possibility and risk a type II error in this largely descriptive, exploratory analysis, we elected to present the statistics and allow the reader to judge the clinical meaningfulness of the differences observed.

This study expanded on earlier efforts by gathering information on the previous treatment involvement of the participants. Many of these jailed veterans with PTSD symptoms had had substantial amounts of previous treatment, including inpatient treatment, for their substance use, psychiatric, and medical problems. Despite such treatment, these veterans were in jail at the time of our study. Given their expenditures on substances, their recent use of substances appears to have been extensive. They reported substantial ongoing psychiatric disturbance and medical problems that interfered with their lives.

A reasonable and testable hypothesis for future research is whether these veterans would be more likely to respond to comprehensive, integrated treatment that included legal counseling, treatment for PTSD, treatment for substance dependence, other psychiatric care, and general health care in a single venue. Although such a comprehensive program would require an infusion of resources, if effective it would likely cost society less than keeping these individuals incarcerated.

Dr. Saxon, Dr. Davis, Dr. Sloan, Dr. McKnight, and Dr. Kivlahan are affiliated with the Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment and Education in Seattle. Dr. McKnight is also affiliated with the department of psychology at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Dr. McFall and Dr. Kivlahan are affiliated with the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. All authors except Dr. McKnight are also with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. Send correspondence to Dr. Saxon at the VA Medical Center (S-116 ATC), 1660 South Columbian Way, Seattle, Washington 98108 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Occurrence of psychological trauma among 128 jailed veterans who completed the Life Event History Questionnaire

|

Table 2. Substance use problems reported by 129 jailed veterans on the Addiction Severity Index

|

Table 3. Psychiatric symptoms and treatment reported by 129 jailed veterans on the Addiction Severity Index

1. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483-492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

2. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907-913, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. VanStelle K, Mauser E, Moberg D: Recidivism to the criminal justice system of substance-abusing offenders diverted into treatment. Crime and Delinquency 40:175-196, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505-512, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Zlotnick C: Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), PTSD comorbidity, and childhood abuse among incarcerated women. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:761-763, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Burton D, Foy D, Bwanausi C, et al: The relationship between traumatic exposure, family dysfunction, and post-traumatic stress symptoms in male juvenile offenders. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7:83-93, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Steiner H, Garcia IG, Matthews Z: Posttraumatic stress disorder in incarcerated juvenile delinquents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:357-365, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Gibson LE, Holt JC, Fondacaro KM, et al: An examination of antecedent traumas and psychiatric comorbidity among male inmates with PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:473-484, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Mumola CJ: Veterans in Prison or Jail. Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jan 2000Google Scholar

10. Kouri EM, Pope HG Jr, Powell KF, et al: Drug use history and criminal behavior among 133 incarcerated men. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 23:413-419, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Stovall JG, Cloninger L, Appleby L: Identifying homeless mentally ill veterans in jail: a preliminary report. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:311-315, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

12. Chilcoat HD, Breslau N: Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:913-917, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048-1060, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kessler RC: Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 5):4-12, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

15. Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:626-632, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. McFall M, Malte C, Fontana A, et al: Effects of an outreach intervention on use of mental health services by veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatric Services 51:369-374, 2000Link, Google Scholar

17. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al: The PTSD Checklist: reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tex, Oct 24-27, 1993Google Scholar

18. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behavior Research and Therapy 34:669-673, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ, Studts JL, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder after treatment for breast cancer: prevalence of diagnosis and use of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C) as a screening instrument. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:586-590, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Spiro A III, Hankin CS, Leonard L, et al: Prevalence of PTSD among VA ambulatory care patients. Presented at the annual meeting of the VA Health Services Research and Development Service, Washington, DC, Mar 22-24, 2000Google Scholar

21. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: An improved diagnostic instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412-423, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. McFall ME, Mackay PW, Donovan DM: Combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder and severity of substance abuse in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53:357-363, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Darnell A, et al: Chronic PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans: course of illness and substance abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:369-375, 1996Link, Google Scholar

25. Roszell DK, McFall ME, Malas KL: Frequency of symptoms and concurrent psychiatric disorder in Vietnam veterans with chronic PTSD. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:293-296, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Schnurr PP, Spiro III A: Combat exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and health behaviors as predictors of self-reported physical health in older veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:353-359, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar