Factors Associated With Noncompliance With Psychiatric Outpatient Visits

Abstract

Adherence to recommended services is essential for long-term effectiveness of ambulatory treatment programs, but factors associated with such adherence are not securely established. We evaluated attendance at 896 scheduled psychiatric clinic visits for 62 patients at a major psychiatric teaching hospital. Visit adherence was found to be significantly higher among patients in an acute stage of illness, those with a personality disorder, those with a post-high-school education, and those living alone. Adherence was also higher when visits were routinely scheduled, when the intervisit interval was shorter, and when the visit entailed psychotherapy rather than pharmacotherapy.

Ensuring patients' adherence to treatment and to clinical appointment schedules is a major challenge in psychiatry as well as in general medicine (1,2,3). The estimated cost of treatment noncompliance for all medical disorders in the United States has been estimated at $100 billion a year (4). Noncompliance with psychiatric treatment is associated with increased clinical, social, and economic costs, and it is closely linked to relapse, rehospitalization, and poor outcome among patients with a major mental illness (5). Previous studies have found that more than a third of appointments for psychiatric care are missed (5), yet research on compliance with clinical appointments (6,7) is much less extensive than research on medication compliance (8).

Fenton and colleagues (1) found that treatment noncompliance may be associated with demographic, clinical, and environmental factors; the effects of medication; and the clinician-patient relationship. Other studies have found an association between appointment noncompliance and youth, male gender, poverty, distance to the clinic, frequency of appointments, former compliance, substance abuse, lack of acute distress, and inexperienced or impersonal clinicians (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). However, results of these studies have been inconsistent.

Our study attempted to identify factors associated with adherence to scheduled outpatient visits at a major psychiatric teaching hospital. From information found in previous studies and our own clinical experience, we predicted that greater appointment compliance would be associated with acute illness, the absence of substance abuse, the presence of psychotherapy, and regular scheduling of appointments.

Methods

Between April and June 1997, a total 1,152 outpatient visits were scheduled for 94 patients at the hospital's outpatient clinics for general psychiatry, psychotic and bipolar disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Of these appointments, 256 were canceled by the staff or had undocumented outcomes, leaving 896 visits by 62 patients for analysis.

The mean±SD age of the patients was 38.5±10 years, with a range of 21 to 69 years; 42 (68 percent) were women; and 48 of the 51 patients for whom ethnic data were available (94 percent) were white. Thirty-seven (60 percent) had a diagnosis of major depressive or bipolar disorder; 15 (24 percent), personality disorder; 15 (24 percent), substance use disorder; 14 (23 percent), schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder; and 10 (16 percent), anxiety disorder. Forty-one (65 percent) had comorbid diagnoses. Twenty-one patients (34 percent) were receiving Medicare benefits, six (10 percent) were receiving Medicaid benefits, 30 (48 percent) had private insurance, and five (8 percent) were self-paid.

The number of appointments kept, visit characteristics, and demographic and clinical factors were determined from hospital medical and billing records. Clinical status at entry into the study was defined as acuity of illness and was based on investigator review of the medical records as close to the time of the missed appointment as possible.

Data were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression models, with visit compliance or noncompliance as the outcome and patient and visit characteristics as covariates. We evaluated the association of visit noncompliance first with patient characteristics (clinical status at entry, education, living situation, psychiatric diagnosis, age, and sex) and clinic type, and then with visit characteristics (routinely scheduled visit, interval between appointments, type of treatment, and missing previous appointments) adjusted by patient characteristics and clinic type. Variables that were not found to be associated with noncompliance did not affect the results, so they were excluded.

The strength of the association between noncompliance and the covariates was calculated by adjusted odds ratios to estimate relative risk. Potential within-subject correlation caused by multiple visits by the same patient was managed with a generalized estimating equations approach with robust variance estimates (10).

Results

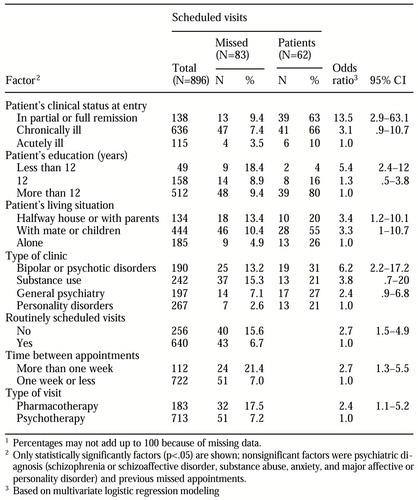

Of 896 scheduled visits for 62 patients, 83 (9.3 percent) were missed by the patients. The factors that were significantly associated with missing a visit are summarized in Table 1. Patients who were acutely ill at entry into the study were found to be more compliant than those who were chronically ill or in partial or full remission, even after the analysis adjusted for intervisit intervals, which were shortest for acutely ill patients. Compliance tended to be poorer among patients with major affective disorders than among those with other disorders, including substance use.

Compliance was much lower for pharmacotherapy and nonroutinely scheduled appointments than for visits for psychotherapy and other routinely scheduled appointments. Psychotherapy visits were much more likely to be routinely scheduled than medication visits (85 percent versus 23 percent). Inclusion of the type of visit and the scheduling status of the appointment indicated that noncompliance was not significantly associated with type of visit; however, noncompliance was associated with whether or not the appointment was routinely scheduled (odds ratio=2.3, 95 percent confidence interval=1.2 to 4.6). Longer intervals between visits were associated with lower compliance rates, even after multivariate adjustment.

Visit compliance was not found to be associated with the number of years a patient had been receiving treatment, the distance from residence to the clinic, the interval between visit scheduling and the date of the visit, or the time of day or the day of the week the visit was scheduled.

Discussion

Adherence to recommended treatment programs is essential to their effectiveness, but maintaining adherence is particularly challenging in the long-term management of both chronic and episodic disorders among patients, who are often ambivalent about diagnosis or treatment. This study adds to a limited and complex literature aimed at early identification of severely ill psychiatric outpatients at risk of clinic visit noncompliance.

The study is limited by its retrospective design, uncertain representativeness of the sample, and reliance on information extracted from records. Nevertheless, we found several factors to be significantly associated with visit noncompliance, including the patient's clinical status—in remission versus acutely ill—whether the visit was a routinely scheduled visit, and the type of visit—for pharmacotherapy or for psychotherapy. These factors have been identified in previous research, but other factors found in our study are less well established. Of particular note is the finding that type of illness had only a minor impact on visit compliance.

Better compliance by more acutely ill patients may reflect personal or family distress, as suggested by previous findings (2,5). In our study, compliance was higher among patients who were living alone than among those who were living with others, suggesting that personal interactions at visits may represent a significant positive social support. Greater adherence among patients in the personality disorders clinic may be partly explained by the larger proportion of psychotherapy appointments in that clinic than in the bipolar and psychotic disorders clinic (90 percent versus 45 percent). In addition, the enforcement of a policy of billing the patient directly for missed appointments, coupled with the termination of therapy if noncompliance persisted, may further explain the large difference in noncompliance rates between the two clinics. The inconsistent relationship between visit adherence and psychiatric diagnosis found in previous studies—and the lack of such a relationship in our study when other covariates were taken into account—further suggests that type of visit is more significant than type of illness.

Conclusions

Our findings offer design features of psychiatric outpatient programs that may enhance visit adherence. In general, social factors and the more personal interactions associated with regular and frequent clinical visits seem more important than demographics or specific psychiatric diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service (National Institutes of Health) grant MH-34370, a grant from the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, and the McLean Hospital Private Donors Neuropharmacology Research Fund. The authors thank Won-Myong Bahk, M.D., and Elisa Cheng, B.A., for their assistance in reviewing the literature and completing the manuscript.

Dr. Centorrino, Dr. Drago-Ferrante, and Dr. Baldessarini are affiliated with the consolidated department of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the bipolar and psychotic disorders program at the McLean Division of Massachusetts General Hospital in Belmont, where Ms. Rendall, Mr. Apicella, and Ms. Längar are research assistants at the experimental therapeutics research unit. Dr. Hernán is with the department of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health. Address correspondence to Dr. Centorrino, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill Street, Belmont, Massachusetts 02478.

|

Table 1. Factors associated with patients' missing scheduled outpatient visits at a psychiatric teaching hospital1

1 Percentages may not add up to 100 because of missing data

1. Fenton WS, Blyer CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637-651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Buckalew LW, Buckalew NM: Survey of the nature and prevalence of patients' noncompliance and implications for intervention. Psychological Reports 76:315-321, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Goldman L, Freidin R, Cook F: A multivariate approach to the prediction of no-show behavior in a primary care center. Archives of Internal Medicine 142:563-567, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Breen R, Thornhill JT: Noncompliance with medication for psychiatric disorders. CNS Drugs 9:457-471, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Delaney C: Reducing recidivism: medication vs psychosocial rehabilitation. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 36:28-34, 1998Google Scholar

6. Campbell B, Staley D, Matas M: Who misses appointments? An empirical analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:223-225, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Grunebaum M, Luber P, Callahan M, et al: Predictors of missed appointments for psychiatric consultations in a primary care clinic. Psychiatric Services 47:848-852, 1996Link, Google Scholar

8. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196-201, 1998Link, Google Scholar

9. Dubinsky M: Predictors of appointments non-compliance in community mental health patients. Community Mental Health Journal 22:142-146, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Liang KY, Zeger SL: Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 73:13-22Google Scholar