Risk Transfer and Accountability in Managed Care Organizations' Carve-Out Contracts

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined characteristics of contracts between managed care organizations (MCOs) and managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) in terms of delegation of functions, financial arrangements between the MCO and the MBHO, and the use of performance standards. METHODS: Nationally representative administrative and clinical information about the three largest types of commercial products offered by 434 MCOs in 60 market areas was gathered by telephone survey. These products comprised services provided by health maintenance organizations, preferred provider organizations, and point-of-service plans. Chi square tests were performed between pairings of all three types of products to ascertain differences in the degree to which claims processing, maintenance of provider networks, utilization management, case management, and quality improvement were delegated to MBHOs through specialty contracts among the various types of products. Contractual specifications about capitation arrangements, risk sharing, the use of performance standards, and final utilization review decisions were also compared. RESULTS: For all types of products, almost all the major functions were contracted by the MCO to the MBHO. Although most contracts assigned some risk for the costs of services to the MBHO, the degree of this risk varied by product type. Except in the case of preferred-provider organizations, a large number of performance standards were identified in MCOs' contracts with MBHOs, although financial incentives were rarely tied to such standards. CONCLUSIONS: MCOs that contract with MBHOs place major responsibility, both financial and administrative, on the vendors.

In recent years, the role of managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) in providing mental health and substance abuse services has grown enormously. Since the mid-1980s, private employers, public purchasers, and managed care organizations (MCOs) have increasingly elected to contract directly with MBHOs, thus "carving out" the provision of behavioral health services. About 68 percent of the U.S. population with health insurance received their mental health and substance abuse services through carve-out arrangements in 2000, an increase of 12.9 percent from 1999 (1). This proportion included those who received services both through direct carve-out arrangements by payers, such as Medicaid and employers, and through contracts by MCOs with MBHOs for the provision of substance abuse and mental health services.

No nationally representative studies have examined the precise nature of carve-out contracts between MCOs and MBHOs. Nevertheless, the details buried in the language of such contracts have the potential to influence how providers interact with patients and how patients seek and receive care. Carve-out contracts can vary significantly in the functions transferred by the MCO to the MBHO, specific financial arrangements, and standards to which the MBHO is held accountable.

We report on the three key dimensions of contracts between MCOs and MBHOs—the functions that are delegated, the financial arrangements between the MCO and the MBHO, and performance standards—by type of managed care product: health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), and point-of-service (POS) plan. We used data from a nationwide survey that determined what behavioral health services were provided by MCOs in 1999.

We have previously studied the motivations of MCOs to carve-out to MBHOs (2), the prevalence of employers' carve-out contracts (3), and specific aspects of these employer carve-outs (4,5,6,7). The goal of this study was to determine the extent of variations in carve-out contracts by using a nationally representative sample of MCOs and to examine the implications of such variations.

Background

Functions included in the contract

There are four functions that MCOs may delegate to MBHOs: formation and maintenance of provider networks, processing of enrollees' claims for payment, utilization and case management, and operation of quality improvement programs.

Formation and maintenance of provider networks. The formation and maintenance of provider networks can entail identifying providers of mental health and substance abuse services who will be available to the health plan's enrollees, negotiating payment arrangements, checking the credentials of providers, profiling patterns of care, and maintaining up-to-date information for enrollees about how to gain access to providers.

Processing enrollees' payment claims. The administrative function of processing enrollees' payment claims involves payment for services rendered.

Utilization management and case management. Utilization management is an approval process for patients' entry into treatment, the amount of treatment they receive, and the mode of treatment. Case management provides a more intensive clinical review of care and tends to focus on patients who have a high use of care.

Operation of quality improvement programs. Quality improvement programs, which vary widely, may include external accreditation by organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance or may provide in-house monitoring of adherence to clinical guidelines or best practices and periodic review of outcomes.

Although most contracts contain these basic building blocks, MCOs still vary in the functions they choose to delegate through carve-out contracts and those they choose to retain. Decisions about the contractual definitions of each function affect the degree of decision making that is transferred from the MCO to the MBHO. Furthermore, payers and patients have concerns about quality of care, access to care, and the risk of undertreatment (8). Therefore, close scrutiny of the scope of functions outlined in carve-out contracts is important, because it can promote accountability of the organization and of the industry.

Financial arrangements

This is the first national study to document the extent of risk outlined in MCOs' contracts with MBHOs for commercial products. Research from the public and private sectors suggests that the amount of financial risk assumed by MBHOs has important implications for the behavior of MBHOs, for enrollees' use of and access to services, for total costs of behavioral health services, and for spending per treatment episode. As more public payers and private purchasers adopt carve-out arrangements, it is increasingly important to assess the amount of risk that is transferred in carve-out contracts.

Types of risk sharing. The sharing of financial risk as outlined in carve-out contracts can be broken down into the amount of risk shared and whether the costs of claims are included. A contract is often referred to as a risk-based contract when some degree of risk for the costs of claims above a specified target is transferred to the MBHO. For claim costs that exceed this target, an MCO's payments to an MBHO may reflect a transfer of all or none of the financial risk or a shared risk on the basis of the MBHO's performance and the extent of losses incurred.

When costs of care fall below annual targets, the MCO may opt to allow the MBHO to keep all, none, or a portion of any resulting savings. The MBHO also may bear some risk if the costs exceed the target, even under contracts that cover only administrative services. Moreover, some portion of the MBHO's payments may be tied to the attainment of specific performance standards.

Implications of risk sharing. Risk sharing between purchasers and MBHOs has been the subject of extensive theoretical discussion and empirical research, because it has important implications for providers and enrollees (9,10,11). When MBHOs can keep cost savings for themselves, they obviously have incentives to reduce costs by using some combination of approaches, including improving efficiency, decreasing the quantity of services they provide, switching to less expensive providers or service sites, and reducing payments to providers. Thus cost-saving incentives in shared-risk contracts have the potential to affect quality, access, and utilization.

Some researchers have maintained that shared-risk capitation will ultimately promote greater integration of behavioral health care and primary care, decrease unnecessary use of services, improve overall health, encourage innovation, and increase effectiveness of care (10). Others have underscored the differential effects of risk sharing and carve-outs on private-sector compared with public-sector enrollees. They have urged public payers to approach risk contracting for behavioral health services with caution in the wake of several unsuccessful managed behavioral health care experiments at the state level (12,13).

Evaluations of risk contracting. Previous research, which has focused largely on empirical case studies of specific employers and vendors—both public and private—has shown that the nature of payment arrangements to MBHOs can create incentives that have both negative and positive effects on MBHOs, providers, and enrollees. Most studies have compared the situations before and after a carve-out (14,15,16). Thus it may be difficult to attribute effects to changes in risk-sharing arrangements or other factors, such as differences in provider networks, utilization review activities, or ways in which patients gain access to care. However, few studies have isolated the effects of financial risk sharing from the overall effects of implementation of a carve-out. For example, in a study of the effect of risk sharing in an employer carve-out, Sturm (17) found that total behavioral health care costs were lower for inpatients but not significantly different for outpatients.

Performance standards

In behavioral health contracts, performance standards identify acceptable levels of performance for various aspects of service delivery, including both administrative and clinical responsibilities (7). These standards may range from requirements for the scope and timing of reports on service use to the achievement of specific levels of satisfaction as indicated in patient surveys. Performance standards formalize purchasers' expectations and MBHOs' accountability. They also may be used for monitoring purposes and to counter any incentives to limit access or otherwise contain costs that might emerge from the contractual risk-sharing arrangements. We examined the extent to which performance standards are contained in contracts between MCOs and MBHOs.

Methods

Data

The data source for this study was the 1999 Brandeis survey on alcohol, drug, and mental health services in MCOs. We surveyed 434 MCOs in 60 market areas nationwide about their commercial managed care products in 1999 and obtained a 92 percent response rate. Data were weighted to provide national estimates of MCOs' provision of substance abuse and mental health services. The study was related to the Community Tracking Study (18), a major longitudinal study conducted in the same market areas by the Center for Studying Health System Change. The Community Tracking Study included a household survey in which respondents were asked to identify their health plans. The results of that survey provided the basis for constructing the sample frame of MCOs for this study.

The sampling unit was each MCO in a specific market area. Thus MCOs that served multiple market areas were defined as separate MCOs for the purposes of this study. We stratified the sampling allocation of MCOs in each market area as either PPO-only or HMO-only and multiproduct. Our sampling strategy allowed us to make national estimates on the basis of our results.

The telephone survey, implemented by Mathematica Policy Research, covered a broad range of domains related to MCOs' provision of behavioral health services (19). Typically the executive director and the medical director from each MCO responded to the survey. However, for some large national or regional MCOs, respondents at the corporate headquarters were interviewed about multiple sites. In some cases we were referred to the MBHO for more detailed information.

We elicited information about the top three types of commercial managed care products in each MCO, resulting in a total of 787 products representing 95 percent of all eligible products offered by the MCOs that responded to the survey. These represent 6,367 products on a weighted basis, of which 39 percent were HMOs, 37 percent were PPOs, and 24 percent were POS products. The 458 products for which there were contracts with MBHOs constituted the sample for our analysis.

Assessing contracting terms

We assessed specific aspects of MCOs' contracts with MBHOs by asking questions about specific functions, financial risk, and performance standards.

When respondents indicated that their MCO had a contract with an MBHO, we asked whether the contract included any of several functions specific to substance abuse or mental health: maintenance of a provider network, claims processing, utilization review, case management, and quality improvement.

To determine the balance of financial risk, we asked whether the rate paid by the MCO to the MBHO covered both claim costs and administrative costs or covered administrative costs only, how much the MBHO had to pay if actual claim costs exceeded the target, and how much the MBHO could keep if actual costs were below the target.

We also asked about performance standards that apply to mental health and substance abuse services: claims processing, patient satisfaction, maintenance of staffing and provider networks, the speed of clinical referrals, quality assurance systems, behavioral health measures from the Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set, patient disenrollment, approaches to complaints and appeals, administrative reporting, provider satisfaction, and telephone responses from member services.

Statistical analysis

The results were weighted to be representative of MCOs' commercial managed care products in the continental United States. The software package SUDAAN (20) was used to allow correction of standard errors for differences in MCOs' probabilities of selection for the survey and for nonresponse. Chi square tests were used to test the significance of differences across product types.

Results

For all product types, we found that almost all the major functions were contracted by MCOs to MBHOs. Although most contracts assigned some risk to the MBHO for the costs of enrollees' use of services, the degree of risk varied. Except in the case of PPO products, a large number of performance standards were identified in MCOs' contracts with MBHOs, although financial incentives were rarely tied to the performance standards.

Functions included in the contract

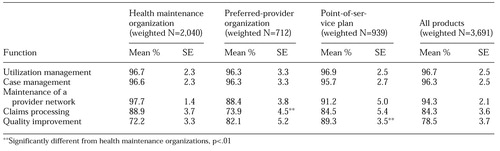

Delegation of functions. Delegation of functions from the MCO to the MBHO was common across the entire spectrum of clinical and administrative functions. More than three-quarters of all contracts covered each of the five key functions, although claims processing and quality improvement were less often included than maintenance of a provider network, utilization management, or case management.

As can be seen in Table 1, more than 95 percent of contracts across HMO, PPO, and POS products delegated utilization management and case management—core functions of behavioral health carve-out contracts—to MBHOs. Similarly, the maintenance of a provider network was included in 94.3 percent of carve-out contracts overall but was found significantly less often (88.4 percent) among PPOs' contracts. MCOs more often retained the function of claims processing than any other function. Only 84.9 percent of products overall and 73.9 percent of PPOs transferred that function to the MBHO. Similarly, across all products, quality improvement was significantly less often delegated to MBHOs. Only 72.2 percent of HMOs, 82.1 percent of PPOs, and 89.3 percent of POS plans delegated this function.

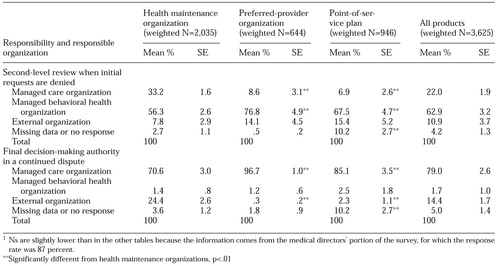

Decision making and dispute resolution. Not all authority for making decisions and resolving disputes was delegated to MBHOs, although almost all MCO contracts specified utilization management as an MBHO activity. Table 2 outlines the allocation of responsibility for the second-level review in the event that initial requests for services are denied and for the final decision in the case of continued disputes. Although MCOs transferred to MBHOs 96.7 percent of the routine utilization review that most patients and providers encounter on a day-to-day basis, as shown in Table 1, they were less likely to transfer the authority for second-level decisions and seldom delegated authority for making final decisions.

The responsibility for the second level of review after an initial request is denied was reported to remain with the MBHO in the case of 62.9 percent of the contracts, to revert back to the MCO in 22.0 of the contracts, and to be delegated to an external organization in 10.9 percent of the contracts. PPOs were more likely than either HMOs or POS plans to delegate this level of authority to the MBHO. MCOs were more likely to remove decision-making authority from the MBHO if cases continued to be disputed. HMOs reported turning over responsibility for final decisions to external organizations more often than PPOs or POS plans. By contrast, PPOs and POS plans reported almost always taking responsibility for the final decision.

Payment arrangements and risk sharing

Several features of the contracts must be examined to provide an understanding of the overall financial relationship between MCOs and MBHOs, including whether the payment arrangement included the enrollees' claim costs for behavioral health services in accordance with a capitated rate, how the MCO and the MBHO shared financial risk, and the amount of the payment, typically on a per-member-per-month basis. Although MCOs provided information about the first two aspects, pilot testing of the survey instrument confirmed that the payment rate was proprietary; thus it was not requested in the survey.

Payment arrangements. In contracts that covered only administrative services, MCOs retained responsibility for the costs of behavioral health claims. However, the MCOs paid administrative fees to MBHOs for the costs associated with member services, utilization review, claims processing, database management, maintenance of provider networks, and any other functions specified in the contract.

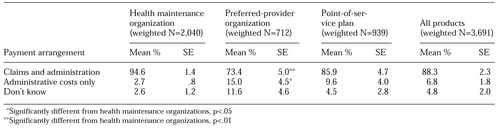

Alternatively, MCOs often paid a capitated rate that covered both the costs of claims for enrollees' behavioral health services and administrative costs. As Table 3 shows, MCOs' contracts with MBHOs typically covered both claim payments and administrative costs, although almost 15 percent of PPOs' contracts were for administrative services only.

Risk sharing. In their contract negotiations, MCOs set a payment rate and also specified how risk or profits are shared if actual costs differ from the target amount, calculated as the sum of the per-member-per-month rate across the total covered enrollees. Table 4 summarizes risk sharing as outlined in contracts that covered both claim costs and administrative services. There was an insufficient number of products with administrative-services-only contracts to enable us to show further details for those contracts.

Risk sharing can be broken down into several categories according to potential financial losses and profits. The first category is no risk to the MBHO. Virtually no HMOs or POS plans and only 6.5 percent of the PPOs had contract terms that had no financial risk to the MBHO—that is, terms under which the MBHO neither bears the risk for claim costs above a target nor garners profits for claim costs below that target. One possible arrangement under a system of partial risk is shared risk that specifies the distribution of excess costs or savings on a percentage basis (12.8 percent of all contracts).

The most common arrangement was full risk, but with a limit on the MBHO's liability or profits (52.8 percent of contracts). Finally, the MBHO can have full risk with no limits. The MBHO bears all the risk for costs above the target but can keep all the profits. This type of arrangement was used in 18.2 percent of contracts.

Liability and profit issues. Disentangling the liability and profit aspects of shared risk also is critical to understanding the MBHO's incentives, because the categories we have discussed can mask the details. MBHOs often risk financial loss if claim costs exceed the capitated amount that has been negotiated with the MCO.

Overall, 55.9 percent of the contracts that covered both claim payments and administrative costs required vendors to bear the entire loss without limit. PPOs and POS plans were significantly more likely than HMOs to have this stringent requirement, but 21.1 percent of the HMOs were not able to provide information on the liability aspect of risk sharing, which could have biased the results. At the other end of the spectrum, only 6.7 percent of the contracts did not require vendors to bear any of the risk for claim costs above the target.

The claim costs throughout a year can fall below the annual target, which in almost all contracts allowed the MBHO to keep some of the profit. HMOs were significantly more likely than PPOs or POS plans to allow MBHOs to retain all of the savings without any limits on their profits. Allowance of full retention of profits was reported by 63.6 percent of HMOs and 32.1 percent of POS plans but only 10.6 percent of PPOs.

Performance standards

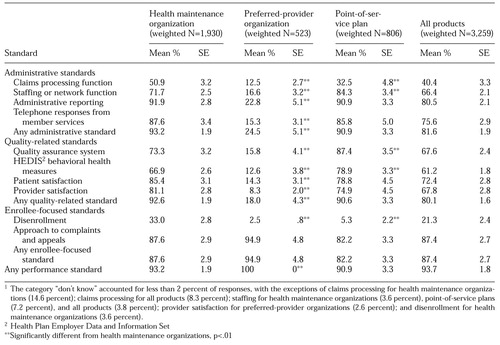

We found that it was common for MCOs to write specific performance standards into their contracts in an effort to make the MBHO accountable to the MCO: at least one such standard was reported for 93.7 percent of the products. However, as can be seen in Table 5, there were systematic variations, both by the type of performance standard and across products.

In the case of administrative performance standards, only 40.4 percent of the products for which claims processing was delegated to the MBHO also held the MBHO accountable by including a claims-processing performance standard in their contract. Two-thirds of the products required staffing standards, 80.5 percent required administrative reporting standards, and 75.6 percent required standards in the area of telephone responses from member services. Across all of these administrative performance measures, PPOs were significantly less likely to include performance standards in their contracts with MBHOs.

In the case of quality-related performance standards, more than 80 percent of the products included in their contracts at least one of the quality standards we asked about (Table 5). Again, PPOs were significantly less likely to report quality-related performance standards.

MBHOs were required to meet disenrollment standards in contracts for only 21.3 percent of the products. However, for 87.4 percent of products overall and 94.9 percent of the PPO products, MBHOs were required to achieve a contract-specified performance level for responding to enrollees' complaints and appeals.

Discussion

When MCOs carve-out behavioral health services to MBHOs, the contracting terms specify the balance of responsibility for managing care, accountability for patients' experiences, and liability for costs. These contract specifications, in turn, can have important implications for enrollees' experiences in obtaining care.

The results of our nationwide survey of MCOs offer a picture of cost-saving incentives that may be tempered by protection for enrollees. Although differences exist according to product type, MCOs usually delegate a broad range of functions to MBHOs and structure the contracts such that MBHOs have at least some financial incentives—often strong ones—to achieve cost savings.

There may also be differences in incentives according to whether the risk lies below or above the target. For example, the assumption of full risk for costs above the target gives the MBHO a strong incentive to keep costs at or slightly below the target. The assumption of full risk on the savings side—that is, allowing the MBHO to keep all savings when costs are below target—means there is no "floor" beneath which the cost-reduction incentives stop operating. If these were the only terms of the contract, policy makers would have serious concerns about the risk of undertreatment of enrollees and of abrogation by MCOs of their responsibility for their enrollees' health services.

However, most MCOs appear to provide counterbalances in their contracts with MBHOs. For almost all products, final decision making in the event of disputes about treatment authorization is retained at the MCO level. However, decision making at this level is required in only rare cases, depending on how often requested services are denied and on the energy that enrollees and providers are able to devote to trying to overturn such denials.

A broad range of performance standards were specified in the contracts for most products, with the exception of PPO products. Such standards are designed to ensure that MBHOs do not pursue efficiency or cost savings at the expense of providing adequate services.

However, the failure of more than 80 percent of products to tie these performance standards to any financial incentives for the MBHO raises questions about the stringency with which the standards are enforced. In some cases, the performance standard applies to a limited number of consumers. For example, although most MCOs track complaints and appeals, the vast majority of problems that consumers experience do not result in a formal complaint. Moreover, even in the absence of performance standards, MBHOs are well aware that MCOs can choose not to renew their contracts.

This threat may have less impact than one might expect, because MCOs may be reluctant to change contractors. Changing contractors is associated with the high cost to the MCO of finding a new MBHO, often through a competitive bidding process; developing a new contract; and establishing new lines of communication. Moreover, such a change would disrupt enrollees' relationships with providers and affect enrollees' knowledge of how to gain access to services.

Of course, our broad review of contract terms must be considered in the context of work that plumbs more deeply into the details of specific contractual relationships between MCOs and MBHOs. For example, our data do not fully reveal the strength of risk-sharing incentives, because we did not determine the dollar amount of the capitated rate or the demographic composition of the enrollees. In terms of an MBHO's bearing the full risk for claim costs above the negotiated target, the stringency of the term "full risk" depends on the level of capitation as well as on the relative needs of the enrollee population. A requirement that an MBHO pay the full claim costs above a generous target creates fewer cost-saving incentives for the MBHO than a requirement that the MBHO pay only part of the costs that exceed a much more stringent target. Similarly, the knowledge that performance measures are written into a contract does not ensure that these measures are strictly monitored or enforced through the application of serious financial consequences for breaches.

The managed behavioral health care field continues to be volatile as large MBHOs deal with consolidation of the industry and respond to new demands for performance accountability. Report cards for MBHOs were recently unveiled by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (21), which also has an accreditation program for MBHOs. In addition, new survey instruments are being developed for evaluating enrollees' experiences of behavioral health care (22). These changes could affect the specific terms of MCOs' carve-out contracts with MBHOs, especially if external organizations take a more active role in monitoring the quality of services provided by MBHOs. In this context, our detailed examination of contract terms provides a baseline for evaluating changes over the next few years and provides a context for studies of specific contracts between MCOs and MBHOs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant RO1-DA-10915 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grant RO1-AA-10869 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The authors acknowledge the contributions of Stephanie Bryson, M.S.W., Robert Cenczyk, Della Faulkner, H.A., Sue Lee, H.A., Willa Sommer, M.A., and Galina Zolutusky, M.S.

The authors are affiliated with the Schneider Institute for Health Policy, Heller Graduate School, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts 02454-9110 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Delegation of functions by managed care organizations to managed behavioral health organizations through contracts, by product type

|

Table 2. Responsibility for resolving disputes about use of behavioral health services by enrollees of managed care organizations, by product type1

1 Ns are slightly lower than in the other tables because the information comes from the medical directors' portion of the survey, for which the response rate was 87 percent

|

Table 3. Payment arrangements in contracts between managed care organizations and managed behavioral health organizations, by product type

|

Table 4. Risk sharing between managed care organizations and managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) as outlined in contracts for claim costs and administrative services, by product type

|

Table 5. Performance standards written into contracts between managed care organizations and managed behavioral health organizations for claims and administration1

1 The category "don't know" accounted for less than 2 percent of responses, with the exceptions of claims processing for health maintenance organizations (146 percent); claims processing for all products (8.3 percent); staffing for health maintenance organizations (3.6 percent), point-of-service plans (7.2 percent), and all products (3.8 percent); provider satisfaction for preferred-provider organizations (2.6 percent); and disenrollment for health maintenance organizations (3.6 percent).

1. Oss M: So much for integration. Open Minds 12, Sept 2000Google Scholar

2. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW: Make or buy: HMOs' contracting arrangements for mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:359-376, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, et al: Why carve out? Determinants of behavioral health contracting choice among large US employers. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 27:178-193, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Horgan CM, Garnick DW, Merrick EL, et al: Structuring behavioral health care: carved out or integrated? Compensation and Benefits Management 16(4):39-46, 2000Google Scholar

5. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Benefits in behavioral health carve-out plans of Fortune 500 firms. Psychiatric Services 52:943-948, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Sciegaj M, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Employee assistance programs in the Fortune 500. Employee Assistance Quarterly 16(3):25-35Google Scholar

7. Merrick EL, Garnick DW, Horgan CM, et al: Use of performance standards in behavioral health carve-out contracts among Fortune 500 firms. American Journal of Managed Care 5:SP81-SP90, 1999Google Scholar

8. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD: Mission unfulfilled: potholes on the road to mental health parity. Health Affairs 18(5):7-21, 1999Google Scholar

9. Rosenthal M: Risk sharing in managed behavioral health care. Health Affairs 18(5):204-213, 1999Google Scholar

10. Goldberg RJ: Financial incentives influencing the integration of mental health care and primary care. Psychiatric Services 50:1071-1075, 1999Link, Google Scholar

11. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

12. Hogan M: Managed public mental healthcare: issues, trends, and prospects. American Journal of Managed Care 5:SP71-SP77, 1999Google Scholar

13. Mechanic D: The state of behavioral health in managed care. American Journal of Managed Care 5:SP17-SP20, 1999Google Scholar

14. Sturm R: Tracking changes in behavioral health services: how have carve-outs changed care? Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 26:360-371, 1999Google Scholar

15. Huskamp H: How a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan affected spending for episodes of treatment. Psychiatric Services 49:1559-1562, 1998Link, Google Scholar

16. Huskamp H: Episodes of mental health and substance abuse treatment under a managed behavioral health care carve-out. Inquiry 36:147-161, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sturm R: How does risk-sharing between employers and a managed behavioral health organization affect mental health care? Health Services Research 35:761-775, 2000Google Scholar

18. Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan HM, et al: The design of the Community Tracking Study: a longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people. Inquiry 33:195-206, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

19. Horgan C, Garnick DW, Merrick E, et al: Substance abuse and mental health services in managed care organizations: results from a nationwide study. Summary Report to Respondents. Waltham, Mass, Brandeis University, Oct 2000Google Scholar

20. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN User's Manual: Release 7.5. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

21. National Committee for Quality Assurance. NCQA's MBHO report card. Available at http://hprc.ncqa.org/mbho/index.aspGoogle Scholar

22. Eisen SV, Cleary PD: The experience of care and health outcomes (ECHO) survey, in 2001 Behavioral Outcomes and Guidelines Sourcebook. Edited by Coughlin K. New York, Faulkner and Gray, 2001Google Scholar