Psychiatrists' Referrals to Self-Help Groups for People With Mood Disorders

Abstract

The study examined psychiatrists' referrals to and support for participation in self-help groups by people with mood disorders. Massachusetts and Michigan psychiatrists with a special interest in patients with mood disorders were surveyed; the 278 respondents represented a 78 percent response rate. About three-fourths of the psychiatrists reported that they made referrals to and felt knowledgeable about self-help groups. However, less than half had self-help literature available or discussed self-help groups with their patients. Beliefs that a patient would gain a better understanding of the illness and would receive support after an episode of illness were positively related to support for self-help. Beliefs that the program was inappropriate and that it lacked professional oversight were negatively related.

The increasing use of self-help groups—18 percent of U.S. adults reported having attended one during their lifetime—has been accompanied by increased availability of self-help groups for people with mood disorders (1,2). Their increased popularity raises the question of whether psychiatrists should make referrals to them. Some psychiatrists are cautious about referrals to groups beyond their direct control. Others believe mental health professionals should actively assist patients to gain access to such groups (3,4). Without such assistance, patients may hear about groups only after a long delay, if at all (5). Even if psychiatrists don't recommend self-help, they may need to raise the topic because two-fifths of those using self-help groups for health conditions do so without their physician's knowledge (6).

Little is known about psychiatrists' interactions with patients in the area of self-help groups. The percentage referring patients to self-help groups for mood disorders is unknown. It is also not known if support for self-help varies according to psychiatrists' personal background, education, practice organization, or beliefs about self-help. This study was designed to explore these issues.

Methods

The sample consisted of psychiatrists listing an interest in affective disorders in the membership directories of the Michigan and Massachusetts Psychiatric Societies. They were sent a questionnaire in 1994. To maximize responses, up to three follow-up mailings were sent. Responses were anonymous; the psychiatrists' names did not appear on the survey. A total of 435 of the 558 questionnaires were returned, for a 78 percent response rate. To ensure qualified respondents, the sample was restricted to psychiatrists who reported two or more contacts per week with patients who had major depression or bipolar disorder and who had definite knowledge of a self-help group for people with mood disorders in their practice area. The resulting sample included 278 psychiatrists.

The psychiatrists were asked whether they knew about groups for people with recurrent major depression or bipolar conditions, referred patients to groups, discussed the groups with their patients, had phone numbers of contact persons for the groups, used literature from groups, and were professional affiliates of these groups. This multicomponent variable was named support for self-help.

Potential predictors of support for self-help were examined using hierarchical multiple regression in a predetermined sequence. First, we examined the number of self-help groups at practice sites to determine whether support for self-help was related to exposure to such groups. Second, we examined psychiatrists' beliefs about the benefits and drawbacks of self-help groups. Third, we examined the predictive value of continuing education about self-help, that is, whether the psychiatrist had received information or education about self-help during the past two years.

Fourth, we examined the relationship between support for self-help and selected characteristics of the psychiatrists' practices (solo or group), treatment model (psychotherapy and medication or clinical management), and the percentage of patients in managed care. Fifth, we looked at background variables of the psychiatrists, including gender, year of graduation, training in self-help during residency, and board certification status. At each step, nonsignificant predictors were dropped, and significant predictors were retained through the last step.

Results

A total of 215 of 271 psychiatrists (79 percent) reported making referrals to self-help groups for people with mood disorders. (Not all of the 278 psychiatrists in the sample answered all questions.) Nearly as many (201 of 277 psychiatrists, or 73 percent) rated themselves knowledgeable about these groups. About the same number (188 of 256 psychiatrists, or 68 percent) indicated that they had the name or phone number of a self-help group. However, only 122 of 278 (44 percent) had self-help literature in their offices, and only 86 of 278 (31 percent) talked to their patients about self-help. Even fewer (31 of 277 psychiatrists, or 11 percent) were professional affiliates of self-help groups.

A total of 207 of 277 psychiatrists (75 percent) were men. Most of them had received their medical degrees in the 1970s (200 of 267, or 75 percent). A total of 180 of 274 psychiatrists (66 percent) practiced in Michigan, and 94 of 274 psychiatrists (34 percent) in Massachusetts. A total of 131 of 277 psychiatrists (47 percent) practiced in groups or hospital and academic settings and 146 of 277 (53 percent) in solo settings. Fifty-six percent of the sample (157 of 278) treated more than ten patients per week with mood disorders.

Overall, respondents reported that about a third of their patients were under managed care. Responses indicated that 230 of 276 psychiatrists (83 percent) preferred the psychotherapy-medication model, and 46 of 276 (17 percent) preferred the clinical management model. Overall, personal background and organizational variables were not associated with support for self-help.

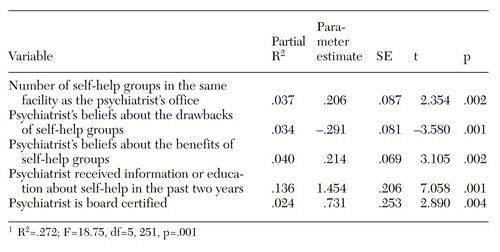

The pattern was different for self-help-specific variables, which were found to be related to support for self-help. The relative importance of the predictor variables was evaluated using hierarchical regression; results are shown in Table 1. Having received information and education about self-help in the past two years was the strongest predictor of support for self-help. Beliefs about benefits and drawbacks of self-help were also strong predictors. Less strong but still significant predictors were the number of self-help groups that met in the facility where the psychiatrist's office was located and whether the psychiatrist was board certified.

After finding significant associations between support for self-help and beliefs about both benefits and drawbacks, we examined the associations between each belief and support for self-help. Two beliefs about benefits—that a patient would gain a better understanding of the illness and would receive support after an episode of illness—were positively related to support for self-help. Similarly, two beliefs about drawbacks—the inappropriateness of the program and the lack of professional oversight—were negatively related to support for self-help.

Discussion and conclusions

In general, the psychiatrists in the survey were knowledgeable about self-help groups and made referrals to them, but they were less supportive insofar as they did not use self-help literature with their patients or discuss patients' experiences with self-help. Overall, support for self-help was unrelated to a psychiatrist's background characteristics and practice variables. However, it was predicted by variables with direct links to self-help, such as the presence of such groups in the same facility as the psychiatrist's office, the psychiatrist's receipt of information or education about self-help, and his or her beliefs about its benefits and drawbacks.

The findings deserve serious attention because of the large sample, high response rate, and anonymous responses. However, we must wait for replication studies to draw confident conclusions, and further research must be done with more representative samples of psychiatrists so that findings can be generalized beyond those with special interests in patients with mood disorders. The decision to survey a group of psychiatrists who would likely be familiar with self-help for people with mood disorders was deliberate. Naturally, psychiatrists who knew of self-help groups in their practice area and saw about ten patients with mood disorders a week might be expected to be better informed about self-help groups for people with mood disorders. Perhaps these informed psychiatrists are trendsetters for other psychiatrists, although no data in the study can confirm this speculation.

It is also not known how psychiatrists' self-reports translate into behavior in relation to self-help groups. Other questions not addressed in this survey are how often psychiatrists use their knowledge and contacts to make referrals, and the criteria they use to decide who is referred to self-help groups. For example, does the number of previous episodes or the quality of the patient's social network influence the probability of referral?

Even if the decision is not to refer patients to self-help groups, mental health professionals may have to become more proactive about self-help because many patients don't discuss their experiences without being encouraged to do so. If the decision is to refer, mental health professionals must be prepared to discuss the possible benefits and risks of participation (7,8,9). Although for some professionals the autonomy of these groups and their accompanying experiential perspective is a major source of benefit, for others the lack of professional oversight is a major risk factor. Perhaps those who weigh the benefits more heavily are reassured by the safeguards built into the structure of these groups and the strong links they maintain with professionals (10). Moreover, professionals can maximize the benefits and minimize the risks by active, ongoing discussions with patients participating in self-help groups.

Mental health professionals who view self-help groups as a potential means to combat feelings of aloneness, enhance personal networks, and promote advocacy have a special incentive to discuss patients' attitudes toward and experiences with self-help groups. They welcome the opportunity to address patients' expectations and doubts about self-help and to recommend that patients visit more than one session of a group, and if possible more than one group, before deciding whether to participate. Yet in the end, the potential benefits of self-help do not erase concerns about referral and support for participation, although they do provide a context for their consideration.

Acknowledgments

This research was partly supported by grant MH-46399 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Julie A. Wheaton, M.S.W., for coordinating the study and Lynn Warner, M.S.W., Ph.D., and William Yeaton, Ph.D., for their helpful comments on the paper.

Dr. Powell is professor of social work in the School of Social Work at the University of Michigan, 1080 South University Avenue, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1106 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Silk is associate professor and associate chair of clinical and administrative affairs in the department of psychiatry of the University of Michigan Health System. Dr. Albeck is clinical instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School in Boston and associate attending psychiatrist at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts.

|

Table 1. Hierarchical regression model of variables predicting support for self-help groups among psychiatrists1

1. Kessler R, Mickelson KD, Zhao S: Patterns and correlates of self-help group membership in the United States. Social Policy 27:27-46, 1997Google Scholar

2. White BJ, Madara EJ (eds): The Self-Help Sourcebook: Your Guide to Community and Online Support Groups, 6th ed. Denville, NJ, American Self-Help Clearinghouse, Northwest Covenant Medical Center, 1998Google Scholar

3. Borkman TJ: Experiential, professional, and lay frames of reference, in Working With Self-Help. Edited by Powell TJ. Silver Spring, Md, National Association of Social Workers, 1990Google Scholar

4. Powell TJ: Self-help, professional help, and informal help: competing or complementary systems? ibidGoogle Scholar

5. Biegel DE: Facilitators and barriers to small group participation. Journal of the California Alliance for the Mentally Ill 6:18-20, 1995Google Scholar

6. Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al: Unconventional medicine in the United States: prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. New England Journal of Medicine 328:246-252, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kurtz LF: Mutual aid for affective disorders: the Manic-Depressive and Depressive Association. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 58:152-155, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wetzel M: Depressive and Manic Depressive Association of Tucson: strengths and limits: report by a bipolar/unipolar self-help group. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 14(4):81-85, 1991Google Scholar

9. Karp DA: Illness ambiguity and the search for meaning: a case study of a self-help group for affective disorders. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 21:139-170, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, et al: The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. Journal of Affective Disorders 31:281-294, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar