A Survey of Police Officers' Experience With Tarasoff Warnings in Two States

Abstract

A desk sergeant at each of 48 Michigan police stations and 52 South Carolina police stations was surveyed about knowledge and experience of Tarasoff warnings. Respondents at 45 stations reported receiving warnings from mental health professionals, with a mean±SD of 3.7±8.4 warnings a year. Only three respondents were familiar with the Tarasoff ruling. Twenty-four stations had a specific policy on such warnings. Twenty-seven stations would not warn a potential victim. Michigan stations were much more likely than South Carolina stations to have experience with or policies on Tarasoff warnings. Because police apparently have limited experience with Tarasoff warnings, calling them may not be the best way to protect potential victims from patients making threats.

After the murder of Tatiana Tarasoff by a graduate student who had earlier consulted a psychologist, the California Supreme Court established a precedent, in 1974 and 1976 rulings, that if a patient tells a mental health professional that he or she intends to harm another person, the professional must take reasonable steps to protect the potential victim (1).

The landmark Tarasoff case has resulted in a dilemma for psychotherapists (2,3,4,5). The court rulings left open to interpretation what actions would discharge the duty to protect an intended victim; warning the victim or notifying local law enforcement officials were mentioned as possible courses of action (2).

The Tarasoff decisions have had an impact beyond California. Many therapists who feel a professional and moral obligation to follow the principles of Tarasoff may have created a new professional standard of care (6). The American Psychiatric Association has offered its district branches a resource document outlining reasonable precautions to prevent harm (7). The recommendations include warning the potential victim; hospitalizing, either voluntarily or involuntarily, the patient who voices the threat; or notifying a law enforcement agency in the vicinity of the patient or in the locale where the potential victim resides.

The purpose of the investigation reported here was to determine whether police in South Carolina and Michigan are knowledgeable about or have experience with Tarasoff warnings.

Methods

In 1998-1999 we telephoned 54 police stations in South Carolina and 50 in Michigan and administered a questionnaire created by the authors. The South Carolina sites included six urban police stations and 48 randomly selected rural sites. The Michigan sites included 25 in the Detroit metropolitan area and 25 randomly selected throughout the state. Police stations in cities with a population greater than 100,000 and stations in the Detroit metropolitan area were considered urban; others were considered rural. Twenty-two of the South Carolina cities had populations below 15,000.

The caller introduced himself as a researcher working in a medical center, explained the study goals and procedure, and obtained verbal informed consent. The questionnaire was administered to a desk sergeant. The questionnaire included seven questions; it also asked about the number of years the respondent had served as a police officer. The police officer was questioned about his or her lifetime experience with Tarasoff warnings by mental health professionals and the number of times during the past year that the officer had dealt with a Tarasoff warning. The officer was asked whether the warnings were systematically recorded, whether the station had specific policies and procedures for handling this type of situation, whether the potential victim would be notified, whether information about the threat would be disseminated to other officers, whether the potential victim would be monitored, and whether the officer was familiar with the Tarasoff rulings.

Comparisons between states and between urban and rural police stations were made by use of chi square analysis. All statistics were computed using SPSS 6.0.

Results

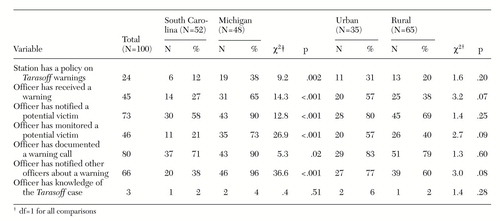

Results are summarized in Table 1. Desk sergeants at 52 South Carolina stations and 48 Michigan stations completed the interview. Four officers declined to participate. No difference was found between states in respondents' years of police experience (mean±SD=16.3±8.2 years). Officers at 45 stations (45 percent) reported that the station had received a warning from a mental health professional. The mean±SD number of warnings received in the past year was 3.7±8.4. Fifty-three officers (53 percent) reported that the station had never received a warning.

Only three officers (3 percent) were familiar with the Tarasoff case rulings. Only 24 officers (24 percent) reported that the station had a specific policy about therapists' warnings. Eighty officers (80 percent) indicated that if a warning was received, they would record the warning. Of those who reported that they would record the warning, 64 officers (80 percent) said that the potential victims would be notified. Among the 20 officers who said that the warning would not be recorded, nine (45 percent) said that the intended victim would be notified. Sixty-six officers (66 percent) reported that the station would distribute the warning notification to other officers, and 46 (46 percent) said that the station would provide some sort of monitoring of the potential victim.

Comparisons between states revealed that police stations in Michigan were much more likely than those in South Carolina to have experience with Tarasoff warnings or to have policies about them. Moreover, Michigan stations were more likely to notify potential victims or monitor them. When the data were combined, urban stations tended to have more experience, were more likely to provide monitoring, and were more likely to notify other police officers.

Discussion

Although mental health professionals may assume that calling the police is an acceptable method of complying with the Tarasoff case rulings, the results of this study highlight the possibility that this may be a flawed assumption (8). Veteran police officers in Michigan and South Carolina had limited experience with Tarasoff warnings and almost no knowledge of the Tarasoff rulings. The majority of police stations in both states did not have policies for handling Tarasoff warnings, and the reported cooperation with mental health professionals varied from station to station.

The lack of experience and knowledge about Tarasoff was particularly evident in South Carolina, although Michigan officers also reported limited experience. The limited police experience with Tarasoff warnings is consistent with a report by McNiel and Binder (9) that found that clinicians do not often make Tarasoff notifications. Rather than calling police, they may hospitalize patients when they are concerned about violence.

The principal differences found in experience, knowledge, and behavior were between Michigan and South Carolina rather than between urban and rural settings. The differences between the two states may indicate that the Michigan population is more urban, informed, or litigious than the South Carolina population. No information about police responses to Tarasoff warnings in other states was obtained, so further comparisons cannot be made.

The findings must be viewed within the limits of the methodology. The investigation had a relatively small sample and evaluated only two states, which have considerable demographic differences. The findings may not be generalizable. Although we sampled a wide range of police stations and found consistent results within states, we did not request copies of police policies, and it is not known whether the officers' responses were valid. Only one police officer at each station was questioned, although the officers questioned were highly experienced.

It is not clear what factors affect how police officers react to Tarasoff warnings in the absence of a policy. The findings suggest that police may need to be trained in police academies or in local communities to better protect potential victims in Tarasoff warning cases. Calling the police may not always be the best way to protect potential victims from threatening patients.

Dr. Huber, Dr. Labbate, and Dr. Hayes Hammer are affiliated with the Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Dr. Balon, Dr. Brandt-Youtz, and Dr. Mufti are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit. Send correspondence to Dr. Huber at the VA Medical Center, 109 Bee Street, Charleston, South Carolina 29401 (e-mail, [email protected]). Parts of this paper were presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 30 to June 4, 1998, in Toronto.

|

Table 1. Experience with Tarasoff warnings among police surveyed in South Carolina and Michigan and comparisons of urban and rural police stations in both states

1. Tarasoff v Board of Regents of the University of California et al, 17 Cal 3rd 425, 131 Cal Rptr 14, 551 P2d 334 (Cal 1976)Google Scholar

2. Roth MD, Levin LJ: Dilemma of Tarasoff: must physicians protect the public or their patients? Law, Medicine, and Health Care 131:104-110, 1983Google Scholar

3. Truscott D, Crook KH: Tarasoff in the Canadian context: Wenden and the duty to protect. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:84-89, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Treadway J: Tarasoff in the therapeutic setting. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:88-89, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Goldstein RL, Calderone JM: The Tarasoff raid: a new extension of the duty to protect. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 20:335-342, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

6. Runck B: Survey shows therapists misunderstood Tarasoff rule. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:429-430, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Appelbaum PS, Zonana H, Bonnie R, et al: Statutory approaches to limiting psychiatrists' liability for their patients' violent acts. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:821-828, 1989Link, Google Scholar

8. Balon R, Mufti R: Tarasoff ruling and reporting to the authorities. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1321, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

9. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Fulton FM: Management of threats of violence under California's duty-to-protect statute. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1097-1101, 1998Link, Google Scholar