Rehab Rounds: Overcoming Barriers to Individualized Psychosocial Rehabilitation in an Acute Treatment Unit of a State Hospital

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Psychiatric rehabilitation begins during the acute stages of a psychiatric disorder and continues throughout the person's lifetime, with the types of services flexibly keyed to the person's phase of illness, needs, and personal goals. During periods of relapse and exacerbation of symptoms, when hospitalization is often required, psychiatric rehabilitation should include the following five objectives: • Clarify how the person's own goals in life, such as a desire for more self-control, freedom of choice, privacy, and time with friends and family, can be served by inpatient treatment and symptom stabilization. • Educate the patient about the nature of his or her illness and how medications work to restore self-control. • Teach the patient about side effects and self-monitoring and negotiating about medication and its effects in a collaborative way with the psychiatrist and other members of the treatment team. • Connect with the family or other natural supports that the person has in the community. • Enable the patient to make appropriate aftercare plans for residential and continuing treatment needs after discharge. When rehabilitation is viewed from the vantage point of these objectives, the inextricable interweaving of "treatment" with "rehabilitation" becomes clear. Treatment and rehabilitation are two sides of the same.It is much easier to integrate psychiatric rehabilitation into more traditional methods of treatment than it is to reorganize a treatment program or facility so that it blends rehabilitation with prevailing treatment imperatives of pharmacotherapy, supervision, and security and safety. In previous Rehab Rounds columns, we have described examples of creative methods for bringing the principles and practices of psychiatric rehabilitation into the treatment milieu (1,2,3).Faced with regulatory criticism from governmental agencies, Dr. Dhillon and his colleagues at Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia, launched a vigorous initiative to bring psychiatric rehabilitation into the forefront of their clinical enterprise. To enable readers to learn from their successful experience and adapt some of the administrative and clinical procedures that worked in Virginia, Dr. Dhillon and Ms. Dollieslager describe the operational details of their odyssey. We believe that their effectiveness in changing a traditional institution can be duplicated in many other places—in units within general hospitals or other community-based settings—as well as in state psychiatric hospitals, where acute treatment has been limited to pharmacotherapy and recreational and diversional activities.

Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia, which opened its doors in 1773, is the oldest public mental health facility in the United States. The adult psychiatry service admits an average of 92 patients each month, all of whom initially enter one of the six wards on the 90-bed acute admissions unit. The average length of stay on the acute wards is 26 days; 79 percent of the patients are discharged to community-based services. The remainder are transferred to longer-stay hospital buildings, which maintain a mean census of 171 patients who have an average stay of 276 days.

In 1993 and 1996 the U.S. Department of Justice cited Eastern State Hospital for not providing sufficient psychosocial treatment to patients on the acute and longer-stay wards. Also in 1996, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), which controls access to federal reimbursement monies, denied certification to the acute admissions program, noting inadequate psychosocial rehabilitation as a factor in the decision.

In response, hospital administrators sought to increase and improve psychosocial treatment activities throughout the hospital. Two immediate actions taken by the hospital administration were the creation of a rehabilitation department charged with providing individualized psychosocial treatment to every patient in the hospital and the retention of Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., and Jeffrey Geller, M.D., as consultants to assist and monitor efforts to develop more active treatment and rehabilitation.

Program development

As the next administrative step, the acute admissions clinical leadership committee, composed of discipline supervisors and senior staff, appointed a program development committee to enhance the psychosocial treatment opportunities available at the hospital. The program development committee included a representative from each discipline and met weekly to assess needs, design programming, and solve problems.

Recognizing the range of problems and abilities presented by patients on the acute wards, the committee's first step was to consolidate psychosocial rehabilitation activities into a single acute psychosocial rehabilitation program, administered through the rehabilitation department. The consolidation allowed for an efficient use of staff resources and provision of services that could meet individualized needs of patients. It was decided to offer psychosocial services in a centralized rehabilitation area rather than on the wards, which was consistent with individuals going to work or school each day.

Group treatments to address problem areas that were thought to contribute to hospital admission were organized into a psychosocial rehabilitation schedule consisting of a menu of options. Treatment teams received profiles of the groups, which included the types of patients likely to benefit from the group, problem areas addressed, and suggested objectives of group participation. For example, the symptom management group was designed for patients whose hospitalization was linked to treatment nonadherence. Group participants learned how to identify the warning signs of their illness and monitor them daily, seek assistance from others when significant changes occurred in their symptom levels, and discuss the need for medication adjustments with their treatment team.

The program development committee actively promoted interdisciplinary responsibility for psychosocial rehabilitation in various other ways. One recommendation, subsequently adopted, was that performance expectations for each discipline be revised to include provision of psychosocial treatment and rehabilitation according to HCFA standards. Moreover, each discipline was expected to commit a specified number of weekly treatment hours per employee.

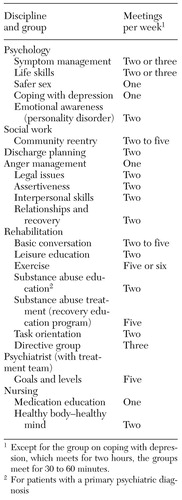

This approach resulted in a weekly schedule of 175 group meetings that emphasized psychoeducational goals; Table 1 shows examples of groups offered by various disciplines. The schedule continued to evolve as the program developed; new offerings were incorporated, and ineffective or underutilized groups were discarded.

Barriers to implementation

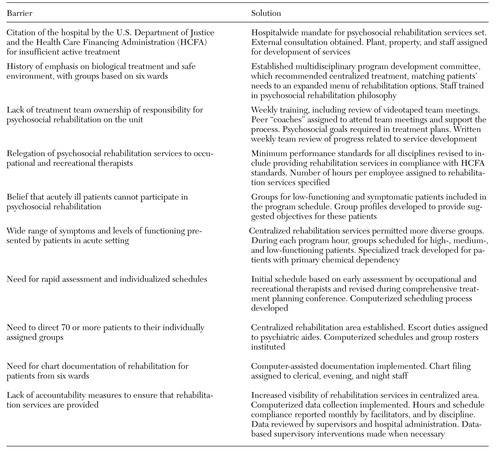

The plan to emphasize psychosocial treatment in the acute admissions program faced substantial challenges to implementation. Recognizing and overcoming these obstacles to incorporating the principles and practices of psychosocial rehabilitation into the treatment plan of acutely ill patients required the kinds of administrative interventions highlighted in Table 2. For instance, many staff members believed that diversionary pastimes such as television watching and naps were acceptable for most patients. In fact, team members often expressed the belief that acutely ill patients were generally unable to participate in psychosocial activities. Moreover, staff members also viewed psychosocial treatment as being in the realm of occupational, recreational, and activity therapists.

To counter these stereotypes, peer "coaches" were assigned to each team to encourage an interdisciplinary focus that included emphasis on psychosocial rehabilitation. Team meetings, which were facilitated by the coaches, were videotaped, and the tapes were reviewed at weekly staff training to ensure widespread attitude change and grassroots involvement in the development of the psychosocial services.

Another vital element was the implementation of the computerized patient contact application. This program, which was created by the hospital's department of management information services, allowed staff to have instant access to patients' schedules and let facilitators know who was scheduled to be in their groups. The patient contact application helped overcome the logistical challenge of making sure that large numbers of patients, many of whom required extra assistance, attended their assigned groups on time; patients' individualized schedules were given to escort staff.

An additional benefit was that this system allowed facilitators to document their progress notes directly on the computer. The patient contact application is the subject of ongoing collaboration between clinical and information technology staff. Revised versions are posted on the network server at regular intervals based on feedback from program users.

Evaluation of program implementation

Incorporating the principles and practices of psychosocial rehabilitation into the clinical approach at Eastern State Hospital has led to a number of changes in day-to-day operations. For example, the patients' individualized schedules have been integrated into their treatment plans, which specify each patient's seven-day assignments. Treatment teams have evaluated the effectiveness of group treatment by monitoring patients' attainment of individualized goals through review of group notes and continuous assessment of patients.

Psychiatrists and their teams have conducted goals groups each weekday morning, which include all patients assigned to their teams. These groups provide opportunities to involve patients in the individualization of their treatment and to improve communication between staff and patients, as well as allowing staff to assess clinical progress. Observations by team members, which include assessment of progress in psychosocial rehabilitation, have been incorporated into the weekly treatment plan. The team's completion of these treatment plans and weekly reviews are included as indicators of quality assurance.

In October 1997, five months after the centralized acute psychosocial rehabilitation program began, the acute admissions program was certified by HCFA. Psychosocial treatment services were described by the HCFA review committee as "excellent." Also, Dr. Geller reported that "Building 2 [acute admissions]… has made great strides in psychosocial programming…. It is commendable that virtually every clinician of all disciplines leads at least one group." He endorsed the central programming area and noted improvements in group documentation. In May 1998 he reported that "the acute program has made absolutely remarkable gains in its psychosocial programming…. Not only has the staff created a psychosocial rehabilitation program on paper, it has successfully implemented this program."

The U.S. Department of Justice, after five years of scrutiny, dropped its investigation of the hospital on March 25, 1999, amid positive reports about the improved level and quality of hospital services.

Patient contact data from 1997 through 1999 revealed 76 percent to 98 percent compliance with the program schedule. This improvement in the compliance rate reflected fine-tuning of the procedures for providing and reporting services in the months after the acute psychosocial rehabilitation program began. The number of hours patients spend in psychosocial rehabilitation groups has more than doubled since reporting began, from about 5,000 hours in the two-month period of November-December 1997 to 12,000 hours in September-October 1999.

In February 1999, a total of 25 nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and other rehabilitation staff responded to a survey that asked for staff impressions about the advantages of psychosocial rehabilitation and its effects on patient care and staff morale. Increased structure and active treatment for patients, who formerly spent most of their days confined to a ward, were most often cited as advantages. Other advantages included improved staff morale, improved individualization of treatment, and improved interdisciplinary collaboration. One nurse commented, "I take pride in being involved in an active treatment program versus custodial care." A social worker reported, "More assessment and more involvement with other disciplines makes us a better team, able to provide more complete treatment." A few staff also reported disadvantages: most common were the competing demands of treatment team duties with those of the still-necessary clinical requirements of supervision, security, safety, and administration of medications.

Patients' responses to a survey about their satisfaction with treatment were also positive and supported basic goals set for the program. Eighty-four percent of those interviewed reported that their treatment groups had helped them understand their illness and its symptoms; 80 percent were able to describe their illness and symptoms; 88 percent reported that their groups helped them understand their medication plan; 96 percent were able to name their medication and its purpose; 76 percent said their groups helped them plan for discharge; 68 percent were able to describe their discharge plan; and 88 percent reported that their groups were very or somewhat helpful to them.

When asked what they liked about the groups, one patient stated, "They keep me busy and motivated." Another patient said, "I like to talk to people with the same problems as me and find ways to solve problems together."

Case vignette

Mr. R, a 38-year-old white male with schizophrenia, was admitted involuntarily with paranoid delusions and homicidal ideations about his parents, following a lengthy period of medication refusal. His admission was preceded by a physical altercation with his father and other aggressive acts toward family members. He was homeless and had several medical conditions, including a cardiac abnormality and a colostomy created several years before admission.

The multidisciplinary assessment revealed many areas in which Mr. R required assistance. Besides his medical problems and lack of housing, Mr. R demonstrated a lack of understanding of his illness, no awareness of the purpose of psychiatric medications, and an inability to use nonviolent techniques for managing his anger. He was assigned to core psychosocial treatment groups, including the medication management and symptom management modules of the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills series (4); the anger management, interpersonal skills, and goals groups; and daily supportive group activities.

In the symptom management group, Mr. R learned how to identify the warning signs of relapse and how to intervene early to prevent relapse once the signs appeared. In the medication management group, he learned how to correctly self-administer and evaluate the effects of antipsychotic medication, as well as how to identify the side effects of medications and negotiate medication issues with his psychiatrist. The anger management group included instructions on how to express angry feelings in a nonthreatening manner.

Originally quiet in groups, Mr. R was participating actively by the second week of his hospitalization. By day 11 Mr. R could name his medications and potential side effects. On day 14 he was asking questions in the group about side effects from his medication. After receiving feedback from group members, Mr. R asked his psychiatrist for a change in medication based on the side effects he was experiencing. The psychiatrist made the change requested by Mr. R. On day 16 he told his nurse that he knew he needed medication to "control aggression and reduce confusion" and that not taking his medication had resulted in two hospitalizations.

In the symptom management group on day 22, Mr. R asked questions about schizophrenia and expressed his frustration about not being understood and about being a "mental patient" who is not believed. On day 36 Mr. R verbally expressed angry feelings about his discharge plan in a prosocial (nonviolent) manner. He was able to negotiate a change in the discharge plan with his social worker, specifying his preference to live in a residential care home rather than with his parents, whom he still mistrusted. He was discharged on day 45, able to clearly discuss his illness and need for medication. He was able to get along well with his parents, although he still verbalized some fixed delusions about them. Six months after hospital discharge, Mr. R was actively participating in community-based treatment.

Afterword by the column editors: The interdisciplinary staff and administrative leadership at Eastern State Hospital have clearly demonstrated that high-quality psychosocial rehabilitation can be provided to acutely ill psychiatric patients in a state hospital setting. The single most important lesson from the transformation of the hospital is the influence of administrative mandates, support, and changes in personnel and scheduling in successfully meeting organizational challenges for program improvement. Giving new job descriptions to clinicians of all stripes that are consistent with the philosophy, principles, and practices of psychiatric rehabilitation and backing them up with new performance standards and appraisals, making computer-based scheduling clinician friendly, and providing hands-on supervision by walking around to give recognition and positive feedback to teams and individual clinicians can make the difference between success and failure.

Change must start at the top, with real changes in the organization instigated by committees clearly charged with bringing about improvements in programming. At Eastern State Hospital grassroots support for rehabilitation accompanied the changes in top and middle management and was facilitated by identifying champions for rehabilitation from among respected peers. These champions served as coaches for the teams as they went through grueling reorganization of their focus and reason for being. Although no manual is available for guiding administrators through the reengineering process, a directory of programs that have successfully made the change to a rehabilitation focus has been published recently (5).

All in all, Eastern State Hospital has demonstrated how state hospitals can become centers of excellence for specialized, tertiary care in the 21st century, rather than the dinosaurs they have often been depicted as. To stem the tide of transinstitutionalization of mentally disabled persons into cheaper community-based human warehouses, jails and prisons, and the streets of our cities, we need to renovate our state hospitals in ways that Eastern State Hospital has demonstrated. The next challenge for Dr. Dhillon and his colleagues will be to maintain high-quality rehabilitation services through implementation of effective total quality improvement procedures.

Dr. Dhillon is medical director of the Colonial Services Board and a consultant at Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia. Ms. Dollieslager is rehabilitation coordinator of the acute admissions program at Eastern State Hospital. Send correspondence to Ms. Dollieslager at the hospital, 4601 Ironbound Road, P.O. Box 8791, Williamsburg, Virginia 23187 (e-mail, [email protected]). Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., and Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Sample groups offered by disciplines at Eastern State Hospital

|

Table 2. Barriers to implementing psychosocial rehabilitation on the acute admissions unit at Eastern State Hospital and the solutions adopted

1. Bopp JH, Ribble DJ, Cassidy JJ, et al: Re-engineering the state hospital to promote rehabilitation and recovery. Psychiatric Services 47:697-698, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Moebius RE, Jones BB, Liberman RP: Improving pharmacotherapy in a psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 50:335-338, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Smith RC: Implementing psychosocial rehabilitation with long-term patients in a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 49:593-595, 1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43-59, 1993Google Scholar

5. Bopp J: Treatment Mall Best Practices Directory. Available from the author, 122 Dorothea Dix Dr, Middletown, NY 10940Google Scholar