Horizons of Context: Understanding the Police Decision to Arrest People With Mental Illness

The police, acting as gatekeepers to the criminal justice system, have long and perhaps incorrectly been identified as the primary contributors to the involvement of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system. The police have been criticized for overzealously arresting people with mental illness ( 1 , 2 ). Researchers have alternately described their use of arrest as a means to "handle" troublesome behavior ( 2 ), as a compassionate gesture ( 3 ), or as being based on beliefs that people with mental illness are more violent than the general population and a danger to the community ( 4 ). This emphasis on police responsibility is perhaps best exemplified by the emergence of police strategies, such as crisis intervention teams, that are designed to enhance police response to this population and are based on the premise that previous police behavior has been inadequate.

For the police, arrest is a relatively rare event. Order maintenance activities, such as patrolling, assisting citizens, and handling nonemergency situations, are more descriptive of how police time is spent ( 5 , 6 ). Police do come into contact with people with mental illness—not only because of troublesome behavior on the part of the person with mental illness but also in a variety of other situations, including police-initiated contact (such as motor vehicle stops), enforcement of court orders, provision of transport for emergency hospitalization, or response after the commission of crimes ( 7 ). It is estimated that police spend approximately 10% of their time involved in situations with people with mental illness ( 8 ). The police arrest people with mental illness for a variety of crimes, ranging from misdemeanor offenses to serious violent crimes, and arrest causes people with mental illness to enter the criminal justice system ( 9 , 10 , 11 ).

In light of concerns about the violence that can result from police interaction with people with mental illness ( 12 ) and what have been described as the inappropriate dispositions that may follow ( 13 ), surprisingly little is known about the elements that shape encounters between police and people with mental illness. Despite extant research on arrest in the criminal justice literature, studies of police interaction with people with mental illness focus almost exclusively on the proximate influences on arrest—namely, how the illness may be related to the arrest. These proximate factors are important but only partially represent the context of the arrest decision. An established framework from which to comprehensively assess whether people with mental illness are disproportionately arrested as a result of their illness does not exist.

This article reviews the research from the criminal justice literature, beginning with Egon Bittner's 1967 work "Police Discretion in the Emergency Apprehension of Mentally Ill Persons," to identify the layers of contextual factors that affect the police decision to arrest people with mental illness ( 10 ). On the basis of this review and case examples, a framework is proposed that incorporates three contexts—manipulative, temporal, and scenic—surrounding the police encounter and the relationship of these contexts to mental illness. Finally, policy and practice interventions of this framework are explored with respect to both police and mental health service mandates.

The criminalization hypothesis

The "criminalization hypothesis" emerged as part of the popular lexicon in the 1970s and 1980s to explain the increasing numbers of people with mental illness found in jails and prisons ( 14 ). The hypothesis states that in the wake of deinstitutionalization and the emptying of state mental hospitals, shorter inpatient hospital stays, and stricter criteria for civil commitment without matching community mental health spending, the criminal justice system became responsible for controlling the sometimes deviant behavior of people with mental illness. Troublesome behavior that had previously been addressed in psychiatric institutions was now treated as a legal violation. Scholars have described jails and prisons rather than psychiatric facilities as the de facto institutions responsible for the care of people with mental illness ( 3 ).

The criminalization hypothesis found support among researchers, policy makers, and the media. Most notably, Teplin ( 2 ) conducted a study of two busy precincts of a large northern city by using trained observers. Her findings suggest that for every type of crime, police underidentify mental illness among the people whom they arrest and arrest people with mental illness more frequently than people without such illnesses. Teplin concluded that the criminal justice system has been employed to address the consequences of deinstitutionalization and the lack of mental health funding. She argued that mental illness has been criminalized ( 2 )—a "fact" repeated in media accounts ( 15 ) and by politicians ( 11 ).

Scholars have since questioned the explanatory power of this approach ( 16 , 17 , 18 ). Criticisms have focused on Teplin's failure to control for environmental and organizational characteristics that typically influence arrest decisions. Specifically, incident-level factors—such as the severity of the offense, the role of substance abuse or community priorities, and resulting police agency policies—were absent from these original studies ( 2 ). Furthermore, this work did not adequately consider the police decision-making process or police behavior—crucial elements of police discretion ( 18 ).

In another test of the criminalization hypothesis, Engel and Silver ( 18 ) found that when the analyses controlled for other factors, police were less likely to arrest people with mental illness, compared with other suspects, and that mental illness can act in some models as a protective factor. These findings have been replicated in subsequent studies ( 19 ). If the criminalization hypothesis is correct and police are wrongly arresting people with mental illness, analyses should show that factors traditionally predictive of arrest are overshadowed by mental illness. It is not clear that this happens ( 18 ). This research suggests that, perhaps, the testing of the criminalization hypothesis requires more thorough specification with models that are informed by the criminal justice literature.

Police discretion and the arrest decision

Police discretion is well studied in the criminal justice literature, and through this research factors have been identified that influence police behavior. The criminal justice literature can be used to inform discussion of police behavior during interactions with people with mental illness in order to understand the arrest decision. Most police work is low visibility, occurring in settings where officers are not monitored by any external authority. In this context, discretion is not one decision—whether to arrest or not—but instead is a series of decision points—when to stop a suspect, how to approach the suspect, when to use force, and finally whether formal sanctions such as arrest are necessary ( 6 , 20 ).

Contextual characteristics of communities, individuals, and incidents all affect discretion ( 20 ). Much of the focus of the criminalization debate, however, has been on the proximate or incident factors—the immediate details of behavior leading up to arrest. Proximate factors are just one group of factors, or "horizons of context," that explain the arrest decision. Other factors will be discussed in the sections to follow.

Horizons of context

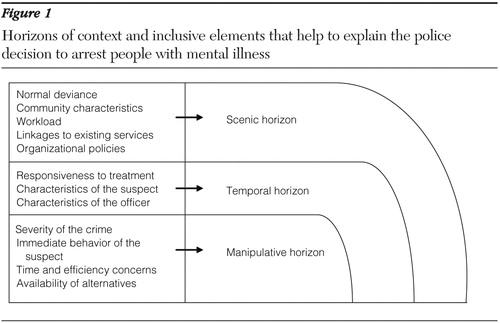

Egon Bittner conducted field work in the 1960s in a large West Coast city where he observed regular interaction between the police and people with mental illness over a ten-month period. On the basis of this work, Bittner described three horizons of context that explain the police decision-making process for emergency apprehensions and the provision of "psychiatric first aid": the scenic, temporal, and manipulative horizons ( 10 ). These horizons can also be used as a framework to explain the factors that influence the arrest decision. First, the scenic horizon is indicative of the features of the community. Second, the temporal horizon includes police knowledge that stretches beyond the specific incident and officer characteristics. Finally, the manipulative horizon involves the current incident from the standpoint of the officer and includes considerations of safety for the community as well as the immediate concerns of the officer. These horizons include the factors that typically influence police behavior during interactions with people with mental illness and are represented in Figure 1 . The discussion of these three horizons that follows builds upon the work of Bittner ( 10 ), and together these three horizons represent the framework from which police officers make decisions about the disposition of people with mental illness.

The scenic horizon

The criminal justice literature suggests that in order to understand the factors that influence arrest, it is not enough to consider only individual or incident characteristics ( 21 ). Environment, although most often overlooked in the criminalization literature, is exceedingly important to understanding arrest, particularly because after deinstitutionalization, people with mental illness become more susceptible to neighborhood influences ( 21 ). The scenic horizon is descriptive of the environment that can inform the police decision regarding the likelihood that an encounter with a person with mental illness can be controlled without arrest ( 10 ). The scenic horizon includes five elements: normal deviance, community characteristics, organizational characteristics, workload, and linkages to community service.

Normal deviance implies that there is a baseline of disorder that the police and citizens are willing to accept. This baseline differs by community and is influenced by local norms and mores ( 22 ). Community socioeconomic characteristics can explain police behavior in terms of arrest, crime, use of force, and police misconduct ( 23 , 24 , 25 ). Although it has been suggested that people with mental illness may be arrested for sociostructural reasons ( 1 ), these measures of neighborhood context are noticeably absent from the literature ( 18 ). Specifically, measures of social disorganization, such as disadvantage and mobility, are relevant to understanding the police decision to arrest during encounters with people with mental illness ( 26 ). Citizens residing in neighborhoods of varying levels of disadvantage rely upon police assistance differently. Because disadvantaged communities often lack structures of informal social control, they must rely heavily on the police to solve disputes ( 27 ). This situation is further hampered by high levels of residential mobility, which often means that neighbors are less likely to help one another ( 28 , 29 ).

Police organizational characteristics can be descriptive of discretion at the administrative level ( 29 ). Brown ( 30 ) hypothesized that the discretionary choices of patrol officers are shaped not only by their own values and beliefs but also by the goals, incentives, and pressures of the bureaucracy. Police organizations are guided by both formal and informal mandates reflective of community preferences ( 31 , 32 ). Command staff, however, ultimately decide which neighborhoods and problems will receive the focus of the organization's resources through the deployment of officers and the provision of training ( 33 )—two areas that may be key to enhancing the police response to people with mental illness ( 9 ).

Another element that has been absent from previous studies of arrest is workload. In general, the busier a district is, the less likely it is that an arrest will be made ( 22 ). Because the police patrol areas differently on the basis of existing levels of crime and disorder, workload can explain some police behavior and should be included in models that predict arrest. Finally, linkages to services in the community are also important for understanding police behavior, because officers who believe that the mental health system is ineffective are less likely to use it in the context of their work activities ( 7 , 34 ). Police may treat people with mental illness differently in communities where there are no mental health resources or where resources are perceived to be ineffective, compared with how they would treat them in communities that are perceived as having effective services ( 11 ).

To illustrate the sometimes competing influences of the elements of scenic horizon, we can look at how they would affect the decision of the police in responding to a woman caught shoplifting $20 worth of food from a neighborhood deli. In this situation, the police consideration of normal deviance is based on the expectations of shop owners who want shoplifters prosecuted. The mayor has promised a crackdown on shoplifting to aid in the area's revitalization, which puts pressure on the officers to make an arrest.

The officers also patrol in a disorganized community, with pockets of high levels of poverty and residential mobility. The police have a high call volume and are eager to be back in service. Shoplifting $20 worth of food is a minor offense, so the officers may remove the woman from the store and release her with a warning not to shoplift again. Releasing the woman would allow the officers to return more quickly to the street to respond to other calls for service. Finally, the officers will consider linkages to community services. If officers know that the neighborhood is rich in services and have had good past experiences with the providers, they may decide to transport or refer the woman to one of the service providers, particularly given the eight-hour block of in-service training that one of the officers recently received regarding interacting with people with mental illness.

The temporal horizon

The temporal horizon is also largely ignored in the criminalization literature and involves police knowledge that stretches beyond the specific incident ( 10 ), including the officer's own background and characteristics of the suspect, such as transience, substance abuse, and mental health needs ( 35 ). Officer characteristics, such as age, gender, education, and experience, may be related to police behavior ( 31 ). Officer mindset can also explain some of the arrest decision, because officers who are empathetic may be more likely to eschew arrest than their more cynical counterparts ( 36 ). Furthermore, it is not unreasonable to suspect that there are police officers who have friends or relatives with mental illness, as it is estimated that between 5% and 20% of the population has a mental illness ( 8 )—a factor that should be considered in mental health and criminal justice research.

Officers may also base decisions on the gender, race, or appearance of the suspect ( 37 , 38 ). Specifically, transience may affect police behavior ( 39 ). King and Dunn ( 39 ) concluded that the police may prefer to deal with troublesome persons in an informal manner, such as removing them from the city limits rather than invoking formal sanctions. Officer knowledge of substance abuse may also affect the likelihood of arrest. Because the possession of drugs is illegal and comes to the attention of the police, people with mental illness who are also substance abusers may first come into contact with the police because of illegal behaviors related to drug seeking, selling, and soliciting. This is particularly salient in understanding the interaction between the police and people with mental illness, because people with mental illness, particularly those with axis I disorders, have a high prevalence of substance use and abuse ( 40 ).

The mental health needs of the suspect and his or her responsiveness to treatment can also explain police behavior. If the officer knows that the suspect has responded to treatment well in the past, an informal disposition may be more likely ( 10 ). Mental health needs are also related to social support, a factor that may be considered in the decision to arrest, particularly when the suspect is impaired ( 10 ). If an officer is aware of social support mechanisms, he or she may be comfortable with the existing linkages to services. In larger cities where police are likely to be unfamiliar with citizens, lack of knowledge about social support and service linkage may be a barrier to informal dispositions.

Returning to our earlier example can help us to understand the influence of the temporal horizon on the police decision to arrest. In this situation, the officers note that the woman caught shoplifting appears to be homeless, as evidenced by her belongings. It is possible that she is also mentally ill. One of the officers is particularly sympathetic to the difficulties of people with mental illness, because he has a brother with a schizophrenia diagnosis. His inclination is to try to link the woman with services rather than arrest her. This officer has five years of patrol experience and has interacted with the woman before in another incident, and in that situation the woman appeared calm. He has no prior knowledge, however, of how she may respond to treatment or whether she has a support network in place, but he does know that she often sleeps in a nearby park. She does not appear to have any family in the neighborhood—meaning that she is lacking both social support and a fixed address.

The manipulative horizon

The manipulative horizon is the set of factors most commonly included in studies of people with mental illness and includes considerations of safety for the community as well as the immediate concerns of the officer. The elements included in this horizon are largely based on the immediate situation ( 10 , 22 ). The manipulative horizon includes the severity of the offense, immediate behavior, time and efficiency concerns, and the availability of alternative resources.

First, officers must consider the type of crime committed; the more severe the offense, the less discretion an officer can employ ( 27 , 41 ), because serious crime is associated with victims who want to press charges, media attention, and political scrutiny. As a result, officers will have little discretion if a person is suspected of committing a serious crime, regardless of his or her mental health status ( 3 ). Officers also consider the relationship between the victim and the suspect, the preferences of the victim ( 42 ), and the use of a weapon ( 18 ). If victims want the police to exercise leniency, the officer will usually respect these wishes ( 27 ).

Next, officers will examine the immediate behavior of the suspect. Troublesome behavior resulting from drug use or psychiatric symptoms can bring people with mental illness to the attention of the police ( 2 ). It may not, however, shape the encounter or be predictive of arrest ( 31 ). Frequently in the police literature, immediate behavior in police interactions is operationalized by a measure of resistance ( 19 , 37 ). The probability of arrest increases when a suspect is disrespectful to the police ( 27 ) or displays extreme hostility ( 22 ). Resistance should be included in any model of police behavior, because recent studies indicate that people with mental illness may be more disrespectful to the police, compared with their counterparts without such an illness ( 19 ).

The police literature suggests that the amount of discretionary time an officer has is crucial to understanding police behavior ( 7 , 43 ). Taking someone for psychiatric help at a hospital has been described as "a tedious, cumbersome and uncertain procedure" ( 10 , 44 ). When officers respond to an incident, they are considered to be out of service. Taking a citizen for psychiatric help at a hospital may present a hurdle for police officers who may be pressured to return to in-service status so that they can respond to calls from the community. In most localities, an arrest takes substantially less time to process than an involuntary hospitalization ( 45 ). No action or an informal disposition can take less time than a hospital transport or even arrest. If, however, the officers have an available alternative that they have found to be efficient ( 34 ), it may be the better choice. Police may prefer to bring a person with mental illness for assistance over arrest if given the opportunity ( 46 ).

To finish our example including the elements of the manipulative horizon, we can see that the severity of crime, immediate behavior, and the time and efficiency concerns will affect the final decision made by the police. In this scenario, the suspect has shoplifted items worth only a small amount. If she also was harassing customers, this might limit the officers' discretion. In this situation, however, the store owner does not want to press charges because the merchandise has been returned. The woman does not have a weapon, and although she is clearly exhibiting troublesome behavior, she has not shown any resistance. In the part of the city where this incident has taken place, there is also an available psychiatric emergency room where the police know that they can quickly get the woman help without getting backed up on calls. Given the entirety of factors that describe this situation, the officers are likely to bring the woman to the psychiatric emergency room or let her go with a warning rather than make an arrest. The officers will then be able to return to in-service status and respond to other calls in the community.

To summarize, the decision to arrest is cumulatively affected by three sets of factors: scenic, temporal, and manipulative. In this example, the police were heavily influenced by the disorganization of the community and resulting workload, coupled with the severity of the crime and the preference of the victim. The factors are listed in Figure 1 .

Discussion and conclusions

Bittner's fieldwork ( 10 ) provides a powerful basis from which to explore police response to people with mental illness. This article builds upon Bittner's work to conceptualize a framework that can explain police discretion. Because police consider a wide range of cues when employing discretionary power, focusing on the manipulative horizon—namely, mental illness as the primary independent variable of interest—has limited our knowledge of police interaction with people with mental illness. Furthermore, the availability of mental health services may not be sufficient to explain the involvement of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system ( 11 ). By ignoring the other factors known to predict arrest, researchers may be oversimplifying police discretion.

Draine ( 47 ) noted that "[police] may use arrest to respond to acute illness, but the extent to which this response represents a 'criminalization' of mental illness is yet unclear, and needs further empirical development." Regardless of the reason, however, many people with mental illness end up in the criminal justice system. Contrary to the criminalization hypothesis, however, social structural factors, such as poverty, transience, and substance abuse, may be more responsible for these outcomes than police behavior. Although strategies such as crisis intervention teams attempt to reduce arrests of people with mental illness by training police and providing individual clinical access, they do not address the underlying sociostructural causes of criminal justice system involvement. As such, the effectiveness of interventions such as crisis intervention teams can be tested only by including a wider range of measures in investigations of police interaction with people with mental illness.

Measuring these horizons is only the first step to understanding the police response to people with mental illness. The next step is to explore interactions between mental illness and elements of each horizon. This is particularly true in the scenic horizon, in which the relationship between social disorganization and mental illness may be more complex than we currently understand. Most research in support of the criminalization hypothesis focuses on people with mental illness who live in disadvantaged areas. Qualitative research can determine whether subgroups of people with mental illness choose to reside in communities where because of normal deviance their behaviors do not elicit attention ( 26 , 47 ) or whether instead these communities serve as homes of last resort ( 48 ).

Additionally, the role of residential mobility should be further explored because it is unclear what effect dense ties in stable neighborhoods have on the criminal justice involvement of people with mental illness. We do not know whether a strong social network decreases criminal justice involvement and how that differs by community. Determining the factors that explain the concentration of people with mental illness who are living in socially disorganized communities is an area for additional research.

In the temporal horizon, the role of stigma in preventing people from accessing services and obtaining employment should be examined ( 49 ). Stigma may be a barrier to social support networks and to positive friendships, both of which can prevent criminal justice involvement. Scholars should focus on the direct and indirect relationships between stigma and criminal justice involvement. In the manipulative horizon, the type and quality of treatment available in different communities may also be explored. People with mental illness, substance abuse problems, and a criminal history may be difficult to treat and therefore be excluded from programs in the mental health system ( 14 ). The absence of viable treatment options for these individuals may push families and neighbors to rely on the police rather than on social services to address "troublesome" behaviors. By examining 911 emergency call data and interviewing callers, researchers can determine the reasons why and in which situations police are needed to address problem behavior.

As a final consideration, there is some question as to how criminalization should even be defined: if a person commits a serious crime, should it matter that he or she also has a mental illness? Some scholars persist in referring to arrest for any offense as evidence of criminalization ( 2 , 18 ). This is a problematic proposition for two reasons. First, police discretion is limited by the severity of the offense, making it incorrect to lump all criminal activity into one category. Second, people with mental illness should be held accountable for serious criminal activity—not all offenders commit crimes because of their illness ( 11 ). Some people with mental illness commit more serious crimes ( 50 ). Failing to hold offenders with mental illness accountable for illegal behavior is beneficial to neither individuals nor communities ( 16 ). This creates a challenge to actors in both the criminal justice and mental arenas to create interventions that hold offenders accountable while also providing necessary treatment. To accomplish this, research models must move beyond the relationship between illness and crime.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported by the Center for Mental Health Services and Criminal Justice Research and by grants P20-068170 and T32-MH070313 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Special thanks to Jeffrey Draine, Ph.D., Nancy Wolff, Ph.D., William Fisher, Ph.D., and Amy Watson, Ph.D., for their helpful suggestions and support during the development of this work.

The author reports no competing interests.

1. Davis S: An overview: are mentally ill people really more dangerous? Social Work 36:174–180, 1991Google Scholar

2. Teplin L: Criminalizing mental disorder: the comparative arrest rates of the mentally ill. American Psychologist 29:794–803, 1984Google Scholar

3. Lamb HR, Weinberger L, DeCuir W: The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services 53:1266–1271, 2002Google Scholar

4. Cuellar AE, Snowden L, Ewing T: Criminal records of persons served in the public mental health system. Psychiatric Services 58:114–120, 2007Google Scholar

5. Goldstein H: Policing a Free Society. Cambridge, Mass, Ballinger, 1976Google Scholar

6. Walker S, Katz C: The Police in America: An Introduction, 5th ed. Boston, McGraw Hill, 2005Google Scholar

7. Finn M, Stalans L: Police handling of the mentally ill in domestic violence situations. Criminal Justice and Behavior 29:278–307, 2002Google Scholar

8. Cordner G: People With Mental Illness. Problem Oriented Guides for the Police. Washington, DC, Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2006Google Scholar

9. Criminal Justice/Mental Health Consensus Project. New York, Council of State Governments, 2002. Available at consensusproj ect.org/thereportGoogle Scholar

10. Bittner E: Police discretion in the emergency apprehension of mentally ill persons. Social Problems 14:278–292, 1967Google Scholar

11. Fisher W, Silver E, Wolff N: Beyond criminalization: toward a criminologically informed framework for mental health policy and services research. Administrative Policy Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33:544–557, 2006Google Scholar

12. Wilson M: When mental illness meets police firepower. New York Times, Dec 18, 2003, N27Google Scholar

13. Teplin L, Pruett NS: Police as streetcorner psychiatrists: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 142:593–599, 1992Google Scholar

14. Teplin L: The criminalization of the mentally ill: speculation in search of data. Psychological Bulletin 94:54–67, 1983Google Scholar

15. Butterfield F: Prisons replace hospitals for the nation's mentally ill. New York Times, Mar 5, 1998, p A1Google Scholar

16. Draine J, Salzer M, Culhane D, et al: The role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Google Scholar

17. Wolff N: When simple solutions are part of the crime: the case of police and citizens with mental illness. Law Enforcement Executive Forum 6:1–24, 2006Google Scholar

18. Engel R, Silver E: Policing mentally disordered suspects: a re-examination of the criminalization hypothesis. Criminology 39:225–252, 2001Google Scholar

19. Novak K, Engel R: Disentangling the influence of suspects' demeanor and mental disorder on arrest. Policing 28:493–512, 2005Google Scholar

20. Walker S: Taming the System: The Control of Discretion in Criminal Justice, 1950–1990. New York, Oxford University Press, 1993Google Scholar

21. Silver E: Neighborhood social disorganization as a cofactor in violence among people with mental illness. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 45:403–406, 2001Google Scholar

22. Klinger D: Negotiating order in police work: an ecological theory of police response to deviance. Criminology 35:277–306, 1997Google Scholar

23. Bursik RJ, Grasmick H: Neighborhoods and Crime: The Dimensions of Effective Community Control. New York, Lexington Books, 1993Google Scholar

24. Kane R: The social ecology of police misconduct. Criminology 40:857–897, 2002Google Scholar

25. Velez M: The role of public social control in urban neighborhoods: a multi-level analysis of victimization risk. Criminology 39:837–864, 2001Google Scholar

26. Metraux S, Caplan J, Klugman D, et al: Assessing residential segregation among Medicaid recipients with psychiatric disability in Philadelphia. Journal of Community Psychology 35:239–255, 2007Google Scholar

27. Black D: The Manners and Customs of the Police. New York, Academic Press, 1980Google Scholar

28. Sampson R: Crime in cities: the effects of formal and informal social control. Crime and Justice 8:271–311, 1986Google Scholar

29. Sampson R: Local friendship ties and community attachment in mass society: a multilevel systemic model. American Sociological Review 53:766–779, 1988Google Scholar

30. Brown M: Working the Street: Police Discretion and the Dilemmas of Reform. New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 1988Google Scholar

31. Terrill W, Reisig M: Neighborhood context and police use of force. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 40:291–321, 2003Google Scholar

32. Wilson JQ: Varieties of Police Behavior: The Management of Law and Order in Eight Communities. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1968Google Scholar

33. Maguire E: Organizational Structure in American Police Agencies. Albany, NY, State University of New York Press, 2003Google Scholar

34. Appelbaum KL, Fisher WH, Nestelbaum Z, et al: Are pretrial commitments used to control nuisance behavior?Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:603–607, 1992Google Scholar

35. Crank J: Understanding Police Culture. Cincinnati, Ohio, Anderson, 1997Google Scholar

36. Muir WK Jr: Police: Streetcorner Politicians. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1977Google Scholar

37. Alpert G, Dunham R, MacDonald J: Interactive police-citizen encounters that result in force. Police Quarterly 7:475–488, 2004Google Scholar

38. Kaminski R, DiGiovanni C, Downs R: The use of force between the police and persons with impaired judgment. Police Quarterly 7:311–338, 2004Google Scholar

39. King W, Dunn T: Dumping: police-initiated transjurisdictional transport of troublesome persons. Police Quarterly 7:339–358, 2004Google Scholar

40. Stuart H, Arboleda-Florez J: A public health perspective on violent offenses among persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:654–659, 2001Google Scholar

41. Skolnick J, Fyfe J: Above the Law: Police and the Excessive Use of Force. New York, Free Press, 1993Google Scholar

42. Paoline E, Myers S, Worden R: Police culture, individualism, and community policing, evidence from two police departments. Justice Quarterly 17:575–605, 2000Google Scholar

43. Worden R: Situational and attitudinal explanations of police behavior: a theoretical reappraisal and empirical assessment. Law and Society Review 23:667–711, 1989Google Scholar

44. Steadman H, Gounis K, Dennis D, et al: Assessing the New York City involuntary outpatient commitment pilot program. Psychiatric Services 52:330–336, 2001Google Scholar

45. Green TM: Police as frontline mental health workers: the decision to arrest or refer to mental health agencies. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 20:469–486, 1997Google Scholar

46. Bittner E: The functions of police in modern society, in Thinking About Police: Contemporary Readings. Edited by Klockars C, Mastrofski S. New York, McGraw Hill, 1980Google Scholar

47. Draine J: Where is the 'Illness' in the criminalization of mental illness?, in Community Based Services for Criminal Offenders With Severe Mental Illness, vol 12. Edited by Fisher WH. Oxford, United Kingdom, Elsevier Sciences, 2003Google Scholar

48. Faris REL, Dunham HW: Mental Disorders in Urban Areas: An Ecological Study of Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses. New York, Hafner, 1939Google Scholar

49. Corrigan P, Watson A, Byrne P, et al: Mental illness stigma: problem of public health or social justice. Social Work 50:363–368, 2005Google Scholar

50. Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski K, Grudzinskas AJ, et al: Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care consumers. Psychiatric Services 57:1623–1628, 2006Google Scholar