A Managed Behavioral Health Organization Operated by an Academic Psychiatry Department

Abstract

As a means of adapting to managed care, the psychiatry department at Wake Forest University developed a managed behavioral health organization (MBHO) to manage the care of enrollees in QualChoice, the health maintenance organization of the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center. Before the academic MBHO was created, care was managed by a for-profit MBHO. In this case study, financial and utilization data were obtained from both MBHOs and from QualChoice. The data confirm that the academic MBHO was able to offer competitive rates for its services. It also was able to increase enrollees' use of the medical center's own providers and facilities by making more referrals than were made by the for-profit MBHO. Developing a managed behavioral health organization can allow academic psychiatry departments, either individually or as consortia, to preserve the patient base they require for teaching, research, and financial stability.

Academic psychiatry departments have established managed care programs, but few accounts of the process have been published. This case report describes the creation of a managed behavioral health organization (MBHO) at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

Managed care has resulted in disproportionate decreases in expenditures for mental health care (1,2). The National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems-Hay Group study found that from 1988 to 1997 the total value of health care benefits for 1,043 U.S. employers declined by 10 percent; general health care benefits declined by 7 percent, but behavioral health benefits declined by 54 percent (3). As a proportion of total health benefit costs, behavioral health benefits decreased from 6 percent to 3 percent during that period.

Utilization patterns also changed. Between 1993 and 1996, use of outpatient behavioral health services dropped 25 percent, but use of outpatient general health services increased 27 percent. Inpatient psychiatric admissions between 1991 and 1996 declined by 36 percent, compared with a 13 percent decline for general health admissions during the same period.

Some academic health centers have dealt with these changes through partnerships with managed care systems (4,5,6,7,8). Partnerships include university health plans, such as the George Washington University health plan; residency programs in health maintenance organizations (HMOs), such as the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound; and affiliations between organizations, such as that between the Henry Ford Health System and Case Western Reserve University. However, because of carved-out mental health benefits, such arrangements do not guarantee the inclusion of psychiatry departments. Although academic departments in general are disadvantaged in competing for managed care contracts because of high overhead (9), psychiatry departments may face the additional disadvantage of MBHOs' preferring lower-cost providers (10), such as master's-level psychologists and social workers, to psychiatrists.

Wetzler and associates (11) have provided one of the few descriptions of an academically based MBHO. They developed a nonprofit management service organization to perform utilization review, credentialing, claims processing, and quality assurance. They also formed a separate integrated provider association with 75 to 100 clinicians drawn from area group practices in addition to clinicians in the psychiatry department. The integrated provider association accepted subcapitation, and the management service organization accepted 15 percent of the capitation rate. After one year, they had contracts with Medicaid and commercial HMOs totaling 100,000 members. Utilization figures for Medicaid recipients were 38 inpatient days and 203 outpatient visits annually per 1,000 members, while persons with commercial insurance used 19 inpatient days and 250 outpatient visits annually per 1,000 members. Financial information was not reported.

Development of the program

In 1992 the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center, which comprises the Wake Forest University School of Medicine and the North Carolina Baptist Hospital, decided to develop its own HMO, QualChoice. It began operating on October 1, 1994, as a wholly owned subsidiary of the medical center. The psychiatry department, anticipating managing mental health and substance abuse services when the HMO was launched, took the lead in developing the plans for those benefits. The department chair (the first author) had been influenced by the experience of chairs at other institutions, who noted that they lost patients after their HMO started because the company administering the plan lacked incentive to refer patients to the department's providers.

As the opening date approached, it was apparent the psychiatry department could not yet provide case management and utilization review services. The department coordinated selection of a national for-profit MBHO to provide these services, and the MBHO used the provider panel developed for QualChoice by the psychiatry department and a toll-free number assigned to QualChoice. The eventual transition of services to the psychiatry department's MBHO was facilitated by QualChoice's having its own provider panel and toll-free number, which made the transition seamless to enrollees. The for-profit MBHO served as a utilization review organization and was not at financial risk.

In October 1995 the chair of the psychiatry department met with QualChoice's chief executive officer to discuss ending use of the for-profit MBHO and beginning capitation with the psychiatry department, which was developing its own MBHO. The chief executive officer was supportive, and the department conducted site visits to four established academic managed behavioral health programs: George Washington University, the Medical College of Wisconsin, Northwestern University, and the University of Cincinnati.

We named our MBHO Wake Forest Behavioral Health Services and set October 1, 1996, as the target date for capitation. The estimated total start-up cost of $150,000 included $100,000 for the time invested by department personnel and $50,000 for consultants and equipment (mainly computers).

By mid-1996 our academic MBHO had developed the necessary infrastructure. Two case managers were hired, and the new MBHO provided case management and utilization review from October 1, 1996, through September 30, 1997, on a per-member, per-month basis. The MBHO assumed up to 15 percent risk depending on whether actual claims were within a specified target range.

The transition to full capitation was delayed until October 1, 1997, one year after the target date. Obtaining the cost data needed to negotiate a fair capitation rate took longer than anticipated, and because this was the first fully at-risk capitated contract for the medical school, the institutional review and approval process took additional time.

Program results

In the following sections we present descriptive information on QualChoice's enrollment growth, enrollees' use of behavioral health services, and changes in referrals and revenue to Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center as a result of switching from the for-profit MBHO to the academic MBHO. In addition, we summarize the effect the transition had on expenditures by Wake Forest University School of Medicine for mental health and substance abuse treatment for medical school employees and their dependents. Comparable data for employees of the North Carolina Baptist Hospital were not available.

Enrollment

Between April 1995 and October 1998, the number of enrollees in QualChoice grew from 19,000 to 75,635. In October 1998, a total of 54,200 enrollees were fully insured through employers, 7,600 were self-funded, and 13,900 were funded by Medicare. Aggressive marketing led to rapid growth in 1997. From October 1996 to October 1998, the total number of enrollees, including both Medicare and commercial patients, increased by 132 percent, from 32,538 to 75,635, and the number of commercial enrollees by 90 percent, from 32,538 to 61,956.

Utilization

Annualized utilization of mental health and substance abuse services during QualChoice's first quarter, October to December 1994, was 47 inpatient days and 1,200 outpatient visits per 1,000 members. By the last quarter in which QualChoice used the for-profit MBHO—July to September 1996—annualized utilization was 38 inpatient days and 835 outpatient visits per 1,000 members. These rates declined further during the first two years of management by our academic MBHO; by September 1998 annualized utilization was 30 inpatient days and 410 outpatient visits per 1,000 members.

Outpatient referrals

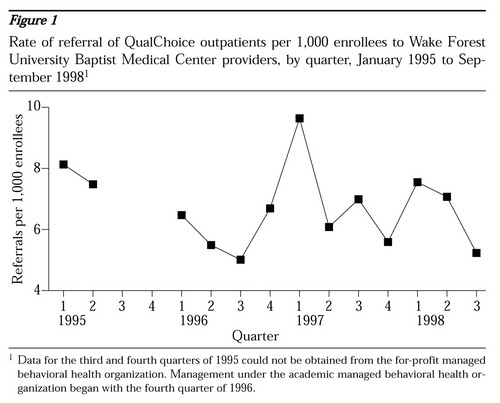

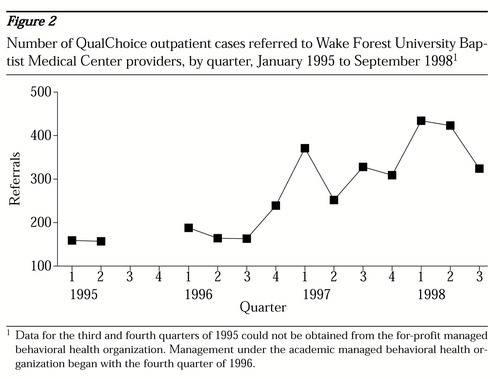

Comparing the number of outpatient referrals to providers at the university medical center by the for-profit MBHO with the number of referrals by our academic MBHO was complicated by the addition of Medicare enrollees during the first year of our MBHO's operation. We therefore compared outpatient referrals for commercial enrollees only, using a Poisson distribution with an overdispersion factor, which accounts for the possibility that the probability of referral is not the same for all people. The Poisson assumption that rates are independent between quarters was verified. A limitation to our inferential procedures was that we had only 13 data points (representing 13 quarters), and hence we focused more on descriptive information than on hypothesis testing.

Figure 1 shows the rate of referrals to providers at the university medical center per 1,000 enrollees under management by the for-profit MBHO and by our academic MBHO. The data show a statistically nonsignificant decrease in the referral rate under the for-profit MBHO from January 1995 to October 1996. During the first year of management by our academic MBHO, referral rates increased and then decreased sharply, although these rates were not significantly different from those under for-profit management. During the second year under our academic MBHO, referral rates were lower than the highest rate achieved under the for-profit MBHO, although the differences were not statistically significant. The lower rate in the second year was a result of the expansion of QualChoice into a 20-county area in northwestern North Carolina, requiring use of providers in that area. Referrals to medical center providers more than doubled between 1995 and 1998.

Figure 2 shows the number of referrals over the same time span. Under management by our academic MBHO, outpatient referrals of commercial enrollees to medical center providers for the 12 months ending September 30, 1997, increased by 77 percent over the previous 12-month period, from 666 to 1,181. This rate of growth exceeded that of enrollment, which increased 44 percent, from 32,538 to 46,928, over the same period. In the last quarter of management by the for-profit MBHO, July through September 1996, the number of referrals was 163; it increased to 239 and 371, respectively, during the first two quarters of management by our academic MBHO, seen as a sharp spike in referral rates in Figure 1. Comparing Figures 1 and 2 shows that as referral rates dropped during 1998, the actual number of referrals to the medical center remained higher during this period.

Inpatient referrals

Under the for-profit MBHO, 78 inpatient referrals of commercial enrollees were made between October 1995 and September 1996. This number grew 21 percent, to 94, between October 1996 and September 1997 after the shift to our academic MBHO, and another 21 percent, to 114, during the following 12 months. Nine additional Medicare inpatient referrals were made between October 1996 and September 1997, and 23 more during the next 12 months.

Outpatient revenue

Billing for outpatient care varied by provider category and service, so we estimated revenue at $450 per patient—six sessions at $75 each, the average for this patient population. Under the management of the for-profit MBHO, estimated outpatient revenue to providers at the university medical center for commercial enrollees from October 1995 to September 1996 was $299,700. Revenues increased 77 percent for this group to $531,450 from October 1996 through September 1997, and another 18 percent to $625,500 over the next 12 months. Because of the time it takes to process and pay claims, the estimated increase in revenue during the first year of management by our academic MBHO is conservative. Outpatient revenue from Medicare enrollees added about 3 percent more to the total for October 1996 through September 1997, and about 5 percent more for the next 12 months.

Cumulative savings

The medical school's annual payment for mental health and substance abuse services for its employees and their dependents decreased from $1,006,683 in 1994 to $576,519 in 1998. Cumulative savings—calculated by subtracting the amount spent each year beginning in 1995 from the baseline amount spent in 1994, and then summing the savings for all years—was $271,328 in 1995 and totaled $1,547,490 by 1998. Savings have been similar for North Carolina Baptist Hospital and the rest of Wake Forest University, but hospital and university expenditures for fiscal year 1994, the year before the start of managed behavioral health care, were not available for comparison.

Discussion and conclusions

Because we had data on the performance of our managed behavioral health organization for only a relatively short period, our focus in this report is descriptive rather than analytical. Some results were achieved just by managing the behavioral health benefit, but we believe others were attributable to establishing our own MBHO. The reduction in expenditures could have been accomplished by any capable MBHO, but the advantage of having our own management was to increase patient referrals to the medical center's providers and facilities.

Even though the increase was not statistically significant, we believe it was appreciably greater than would have been accomplished by the for-profit MBHO. Three observations support this belief. The first is the spike in the outpatient referral rate to our providers after the change. When a caller had not yet selected a provider, our case managers asked, "May we refer you to a Medical Center provider?"—a question we had tried unsuccessfully to have the for-profit MBHO include—and outpatient referrals to the medical center doubled to 50 percent of all referrals almost immediately.

Second, a subsequent decline in the referral rate to medical center providers is explained by expansion of enrollment in new areas, requiring greater use of out-of-area providers. Third, the absolute number of referrals to our providers remained greater than it was under management by the for-profit MBHO even as the referral rate was declining.

Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center has benefited financially in two ways. When behavioral health care utilization was managed, these costs for the medical center's own employees and their dependents were halved. Second, under our MBHO, more of the services were provided at the medical center.

The establishment of our own MBHO has benefited the department of psychiatry financially in three ways. First, departmental clinical revenue increased. Second, the service supported department personnel salaries, such as that of its medical director. Third, the profits supported the academic mission rather than being returned to shareholders. Another advantage was that the department had the authority to decide where to cut costs, enabling it, for example, to reduce profit margins before reducing provider fees—just the opposite of a for-profit MBHO's likely course.

QualChoice's enrollees fall under two behavioral health benefit structures. Most QualChoice contracts offer 20 outpatient visits and 30 inpatient days annually—the "standard" benefit—while the QualChoice contract with the Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center offers 40 outpatient visits and 60 inpatient days. This richer benefit is virtually equivalent to parity, although parity is not required in our state. Both plans offer a point-of-service option whereby enrollees can choose a provider or facility not on the panel, but with higher copayments and deductibles. Behavioral health benefits nationally are now approximately 3 percent of total health care costs (3), and QualChoice's standard behavioral health benefit is comfortably beneath this figure, with per-member, per-month costs within the $2.75 to $3.50 range usually found in our area.

The main drawback to the department of psychiatry of developing our own MBHO has been the time involved. However, this activity has proved to be complementary to academic pursuits, as we are preserving our patient base, our residents learn about managed care, and the service provides data for health services research. Also, developing the MBHO allowed us to make changes beneficial for other managed care contracts, such as a centralized computer-based patient appointment system.

Academic MBHOs represent an alternative to a disturbing development. The largest for-profit MBHOs have grown by buying smaller companies; one has accumulated $1.3 billion in debt, with debt service costs of $.45 per member per month (12). Under such circumstances the easiest way to make a profit is to reduce provider fees, which is what happened in New York, where three large companies, including the one referred to above, decreased reimbursement rates by 10 to 40 percent for many CPT codes effective January 1, 1999 (13).

Academic psychiatry departments should take the lead when institutional managed care discussions begin. Our experience suggests that such leadership is welcome and may preempt the institution's selecting a for-profit MBHO. As one faculty member said with a touch of cynicism, "The only thing worse than being in managed care is not being in it."

We believe the public interest is served by academic psychiatry departments—either individually or as consortia—developing the capability to serve as MBHOs and contracting directly with HMOs and employers. Academic centers exist to improve the health and health care of the nation through clinical care, teaching, and research, and developing an MBHO is a means to that end. For-profit companies, by contrast, exist to make a profit for their shareholders, and behavioral health care is a means to that end.

Academic psychiatry departments must train the next generation of psychiatrists and advance clinical care through research—missions that require a patient base and financial stability. Establishing an MBHO will be necessary for some departments, and our experience demonstrates the potential benefits to the department and the institution.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Allen Daniels, Ed.D., for his guidance throughout the development of Wake Forest Behavioral Health Services. The authors also thank Marsha Honeycutt and Lynette McDowell for their assistance.

When this study was completed, the authors were with the department of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where Dr. Reifler, Dr. Rosenquist, and Dr. Teeter remain affiliated. Ms. Briggs is now chief executive officer of Carolina Behavioral Health Alliance, Dr. Colenda is with the department of psychiatry at Michigan State University, Ms. Yates is with Partners Health Plan of North Carolina, and Dr. Reboussin is with the department of public health sciences. Send correspondence to Dr. Reifler, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Medical Center Boulevard, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157-1087 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Rate of referral of QualChoice outpatients per 1,000 enrollees to Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center providers, by quarter, January 1995 to September 19981

1 Data for the third and fourth quarters of 1995 could not be obtained from the for-profit managed behavioral health organizationManagement under the academic managed behavioral health organization began with the fourth quarter of 1996.

Figure 2. Number of QualChoice outpatient cases referred to Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center providers, by quarter, January 1995 to September 19981

1 Data for the third and fourth quarters of 1995 could not be obtained from the for-profit managed behavioral health organizationManagement under the academic managed behavioral health organization began with the fourth quarter of 1996.

1. Inglehart JK: Managed care and mental health. New England Journal of Medicine 334:131-135, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Frank R, Huskamp HA, McGuire TG, et al: Some economics of mental health "carve outs." Archives of General Psychiatry 53:933-937, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Health Care Plan Design and Cost Trends:1988 Through 1997. National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems. Washington, DC, Hay Group Management, Inc, 1998Google Scholar

4. Stevens DP, Leach DC, Warden GI, et al: A strategy for coping with change: an affiliation between a medical school and a managed care health system. Academic Medicine 71:133-137, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Karp S, Langschwager L, Gamliel S, et al: The need for comprehensive data on educational affiliations between academic health centers and managed care organizations. Academic Medicine 72:341-346, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lenaz M: Research promotion between managed care organizations and healthcare delivery systems. Connecticut Medicine 62:39-40, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

7. Phillips RR, Lee MY, Berman HA, et al: The Tufts partnership for managed care education. Academic Medicine 72:347-356, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Nash DB, Veloski JJ: Emerging opportunities for educational partnerships between managed care organizations and academic health centers. Western Journal of Medicine 168:319-327, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

9. Carey RM, Engelhard CL: Academic medicine meets managed care: a high-impact collision. Academic Medicine 71:839-845, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Meyer RE: The economics of survival for academic psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry 17:149-160, 1996Google Scholar

11. Wetzler S, Schwartz BJ, Sanderson W, et al: Academic psychiatry and managed care: a case study. Psychiatric Services 48:1019-1026, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Schreter RK: Uncertain market opens the door for new strategies in promoting wellness. Psychiatric Practices and Managed Care 4(6):3-11, 1998Google Scholar

13. Slashed reimbursement rates anger New York psychiatrists. Psychiatric News, Jan 15, 1999, p 5Google Scholar