The Impact of a Token Economy on Injuries and Negative Events on an Acute Psychiatric Unit

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although the use of token economies has been shown to facilitate patient change and improve program functioning in numerous settings, token economies have received little attention in acute psychiatric settings. A token economy was introduced on an acute care unit in a rural hospital, and rates of negative events were compared before and after implementation. METHODS: Negative events were defined as patient and employee injuries that were not accidents. Unauthorized absences and use of emergency medications were also counted as negative events. Rates of negative events were calculated over two four-month periods, before and after the token economy was introduced on a 24-bed acute care unit that housed the hospital's neo-adult program for patients between the ages of 18 and 20. The unit also served as an admitting unit for patients over age 20. RESULTS: When the analysis controlled for unit census and the number of neo-adults, an analysis of covariance indicated that the number of negative events fell significantly after the token economy was introduced, from 129 in the four months before implementation to 73 after implementation, a 43 percent reduction. Both staff and patient injuries were significantly reduced. A small increase in use of emergency medications was noted, but it was not statistically significant. CONCLUSIONS: Findings support the use of the token economy in acute settings to improve the unit milieu by reducing negative events.

Token economies have long been shown to be an effective technology for facilitating change in psychiatric settings (1,2,3). Patients earn reinforcers in the form of tokens for engaging in targeted behaviors. The tokens are then exchanged for desired items or privileges.

The token economy can help clients perform desired activities and learn desired behaviors. It offers a useful and flexible format to target a wide range of difficulties. Described as a treatment delivery system and a way of providing learning principles to address specific problems (4), the token economy can be tailored by an individual treatment setting to fit the needs of its client population. Two token economies may not target similar behaviors but may use the same basic principles. Because of this flexibility, the efficacy of token economies has been demonstrated in a variety of inpatient settings and with numerous populations. They have included chronic psychiatric patients (1,5), mentally retarded adults and children (6,7), patients with brain injuries (8), and individuals in alcohol treatment (9,10).

Even though abundant evidence supports the efficacy of token economy systems, relatively little research has been published on the use of token economies in acute psychiatric settings. A search of PsycLit and MEDLINE for the years 1980 to 1998 with the keyword "token economy" yielded 313 abstracts, only two of which clearly identified an acute psychiatric setting as the studied environment (10,11).

Why is the token economy receiving limited attention in this setting? Part of the answer may be fundamental misunderstandings of the mechanisms and impact of the token economy. Corrigan (12) reviewed many of the basic misconceptions about token economies. Some fallacies that are likely impeding the development of token economies in acute care settings are beliefs that they are abusive and do not foster individual treatment plans and that milieu management is not the primary concern of treatment teams.

Although few studies of token economies have been conducted in the acute care setting, this environment presents multiple opportunities for the token economy to make a direct impact, specifically in controlling unit discord. The token economy has been shown to reduce violence in various treatment situations, such as for patients in alcohol treatment (10), chronic psychiatric patients (2,13), and those with severe head injuries (8).

Because of the effect on negative events that the token economy has demonstrated in other settings, this study evaluated the impact on negative events of a unitwide token economy in an acute psychiatric unit in a rural state facility. It was hypothesized that the token economy would facilitate a safer and more stable environment through reduction of staff injuries, patient injuries, unauthorized absences, and psychiatric emergencies.

Methods

The unit

The study was conducted on a 24-bed inpatient psychiatric unit, one of six units in a 150-bed state psychiatric facility accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. The unit serves as a general admission unit and includes the hospital's Medicaid-funded neo-adult program. The neo-adult program serves all patients admitted to the hospital between the ages of 18 and 20 years and provides extra services specifically designed for this age group. Patients over age 20 are admitted to the unit on a rotating basis with the other admission units. All patients on the unit are involuntarily committed.

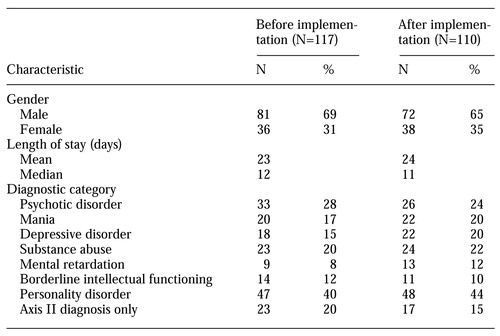

Patients admitted to the unit have various diagnoses including chronic mental illness, severe personality disorders, and dual diagnoses. Table 1 presents the diagnostic categories of patients admitted to the unit during the four-month periods before and after implementation of the token economy and the average length of stay during those periods. The high mean lengths of stay were due to two patients in each sample who were housed for more than six months pending court action on legal charges.

The token economy

The token economy system was implemented on the neo-adult unit because the level of negative events there was consistently higher than on other units. Initial attempts to implement the token economy in 1996 were resisted by state advocacy groups due to concerns that the program would be punitive and would fail to provide individualized treatment. To help allay these concerns, the program was required to be voluntary. However, since the program became operational in March 1997, more than 98 percent of the patients admitted to the unit have enrolled in the program. No additional resources or staff were provided for the implementation and maintenance of the token economy.

Staff were trained using both classroom and hands-on training. A substantial percentage of the staff—approximately 25 percent—had previous experience in a token economy system while working with chronic populations or patients with mental retardation. Initially, a majority of the staff were exposed to the specific rules, procedures, and interventions of the program in a day-long classroom session. Staff who were not able to attend the large session were trained in shorter, more intensive sessions that fit unit scheduling.

Classroom training consisted of a review of a manual prepared by the author, question-and-answer sessions, and role playing. After the classroom training, a one-week trial period was conducted on the unit. During this time senior staff, the unit psychologist, and experienced staff provided hands-on instruction for other staff members in the procedures and verbal interventions. During the on-unit training, patients collected tokens but were not required to spend them for privileges. This procedure allowed patients and staff to become comfortable with the procedures. Further mistakes would cause minimal disruption, and patients could build a bank of tokens to spend.

When a patient was admitted to the unit, staff members provided the patient with a token sheet on which tokens in the form of ink-stamps were collected. At that time, staff members explained the rules and procedures. Staff also provided prompts to patients about the rules and the need to collect and use tokens. Lists of the activities that would earn tokens and items for which tokens could be spent were posted on the unit.

The token economy that has been developed on the unit combines unitwide and individual behavior plans. The basic mode of the program is reinforcement of desired behavior. The use of response costs—the loss of tokens for inappropriate behavior—is limited. Patients earn points for engaging in therapeutic activities, groups, assessments, and individually targeted behaviors. Patients also may earn points for keeping their room clean and rising early in the morning. Patients exchange tokens for extra smoke breaks, off-unit grounds passes, television time, movies, trips to snack machines and the canteen, and similar activities.

Access to these reinforcers is limited by a system in which patients progress through several levels based on safety needs. Individuals on close constant observation or 15-minute safety checks are not allowed to purchase extra smoke breaks (five per day are provided for free). Only individuals who reach the highest level are allowed grounds passes.

The only behaviors that require a response cost are violations of major safety rules, such as patients' smoking in their bedrooms, and behaviors that would cause the police to become involved if they occurred outside the hospital, such as hitting someone, threatening someone, and destroying property. These violations result in the loss of all unspent tokens and restriction to the unit for 72 hours. During the 72 hours, patients can continue to earn all available tokens but can only spend tokens on extra smoke breaks.

Individual plans target specific patient needs, such as increasing eating, improving hygiene, reducing cursing, and decreasing self-mutilating behavior. A patient either earns extra tokens for performing a desired behavior or pays tokens for performing an undesired behavior.

Design and procedure

Two four-month periods were assessed in the study—the first period, from October 1996 through January 1997, without the token economy, and the second period, from April 1997 through July 1997, with the token economy. Before implementation of the token economy, staff members participated in group training sessions in which the policies and procedures were discussed and role playing of the proper administration of tokens was performed.

The number of negative incidents during both periods was compared. The collection of information about negative incidents is required for all units as part of the bylaws and procedures of the facility. Negative incidents were defined as staff and patient injuries that were not accidents; the definition also included absences without leave and elopements and psychiatric emergencies. Psychiatric emergencies were incidents in which emergency medications were used because of a patient's behavior. Staff and patient injuries were defined as injuries that required any form of medical attention, the lowest threshold of attention being the need for a visual examination of the injured area.

Results

The numbers of neo-adult days in the periods before and after implementation were comparable (593 and 596, days, respectively), as were the total numbers of patient days (2,701 and 2,662, respectively).

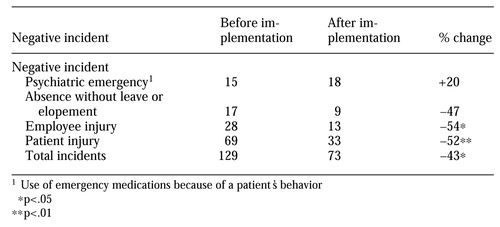

A one-way analysis of covariance was used, with the number of neo-adults and the unit census used as covariates. As shown in Table 2, the rate of negative incidents on the unit was significantly lower after the token economy was implemented (F= 11.75, df=1,241, p<.05). Results indicate a 43 percent reduction in the total number of negative incidents, from 129 in the four months before implementation to 73 after implementation. Both staff and patient injuries were significantly reduced. A small increase in psychiatric emergencies was noted, but it was not statistically significant.

The number of days in which at least one negative incident occurred was also calculated for both periods. In the 123-day period before implementation, a negative incident occurred on 57 days (46 percent of the total days). In the 122-day period after implementation, a negative incident occurred on 38 days (31 percent). The difference between periods was significant (χ2=5.96, df=1, p<.05).

Discussion

The findings demonstrate the impact that a token economy can have on the functioning of an acute psychiatric unit. They provide strong evidence that the number of staff and patient injuries can be decreased through the use of a unitwide behavioral program. Improved safety for both staff and patients may allow administrators and staff members to focus their attention more on treatment and less on maintaining control of the unit.

This study should motivate re-examination of the role of token economies. Past research has largely focused on chronic populations of various types with specific and similar needs, such as increasing appropriate social interactions and improving self-care skills. It is likely that this focus has prevented clinicians from recognizing the wider range of behaviors that can be targeted. Staff on acute care units are constantly aware of the need to decrease danger to patients and others. The token economy can be modified to target behaviors leading to negative incidents.

Although this study demonstrated the utility of the token economy in an acute care setting, the findings may not be generalizable to very acute settings with stays of three or four days. Studies examining the very acute setting should focus on quite specific short-term goals such as socializing, medication compliance, and group participation as ways of improving treatment. An advantage of the token economy system for very acute settings is its encouragement of self-directed and self-motivated behavior toward goals. Furthermore, planning and delay of gratification are central products of the token economy. Such factors are likely more relevant to returning patients to self-sufficiency than respite and medication adjustment alone.

To implement a token economy, an acute care treatment unit should clearly identify unitwide targets for all patients and then supplement these targets with individual treatment goals and individual behavior plans. However, a note of caution should be raised. Because of the potential for abuse if a token economy is improperly implemented, programs that use token economies must strive to limit response costs and aversive contingencies. Programs should focus on providing reinforcers to increase the frequency of desired behaviors and to reduce undesired behaviors by reinforcing alternative behaviors. With appropriate planning and a focus on facilitating positive behavior, the token economy will help improve unit management and treatment.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the work of Scott Pollard, M.D., Linda VanHorn, R.N., and Melanie McGhee, R.N., in the implementation of this program.

Dr. LePage is affiliated with the department of behavioral medicine and psychiatry at the West Virginia University School of Medicine and Sharpe Hospital, P.O. Box 1127, Weston, West Virginia 26452 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Diagnoses and length of stay of patients treated on an acute care unit in the four-month periods before and after implementation of a token economy

|

Table 2. Negative incidents occurring on an acute care unit in the four-month periods before and after implementation of a token economy

1. Allyon T, Azrin NH: The Token Economy. New York, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1968Google Scholar

2. Paul GL, Lentz R: Psychosocial Treatment of the Chronic Mental Patient: Milieu Versus Social Learning Programs. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1977Google Scholar

3. Liberman RP: Schizophrenia practice guideline (ltr). American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1792-1793, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

4. Paul GL, Stuve P, Cross JV: Real-world inpatient programs: shedding some light—a critique. Applied and Preventative Psychology 6:193-204, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Glynn SM: Token economy approaches for psychiatric patients: progress and pitfalls over 25 years. Behavior Modification 14:383-407, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hurley AD, Sovner R: Behavior modification: III. the token economy. Psychiatric Aspects of Mental Retardation Reviews 4:1-4, 1985Google Scholar

7. Sisson LA, Dixon MJ: Improving mealtime behaviors through token reinforcement: a study with mentally retarded behaviorally disordered children. Behavior Modification 10:333-354, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wesolowski MD, Zencius AH: Treatment of aggression in a brain-injured adolescent. Behavioral Residential Treatment 7:205-210, 1992Google Scholar

9. Carpenter R, Casto G: A simple procedure to improve a token economy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 13:331-332, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Franco H, Galanter M, Castaneda R, et al: Combining behavioral and self-help approaches in the inpatient management of dually diagnosed patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 12:227-232, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Crowley TJ: Token programs in an acute psychiatric hospital. American Journal of Psychiatry 132:523-528, 1985Google Scholar

12. Corrigan PW: Use of a token economy with seriously mentally ill patients: criticisms and misconceptions. Psychiatric Services 46:1258-1263, 1995Link, Google Scholar

13. Dickerson F, Ringel N, Parente F, et al: Seclusion and restraint, assaultiveness, and patient performance in a token economy. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:168-170, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar