Datapoints: Satisfaction With Managed Care Among Persons With Bipolar Disorder

Managed behavioral health plans typically require preauthorization for services and refer patients to restricted lists of providers. People with bipolar disorder may be at risk for not receiving necessary services if they have difficulty complying with authorization procedures or maintaining relationships with their clinicians.

In March 1997 we surveyed members of a national voluntary case register of persons with bipolar disorder maintained at the University of Pittsburgh. Diagnostic validity efforts found that 93 percent of the registrants met criteria for a lifetime bipolar-spectrum diagnosis. Of the 1,507 registrants, 848 returned the survey. This analysis focuses on the 370 persons covered only by private insurance who provided data about their health plan.

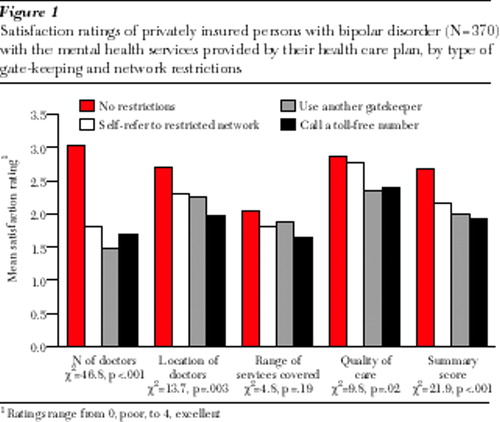

To examine restrictions on care, we categorized respondents into four groups: self-referral to any mental health provider, self-referral to a restricted provider network, referral through another gatekeeper such as an employee assistance program, and referral through a toll-free number.

To examine respondents' level of satisfaction with their health plan, we asked them to rate the plan on a 5-point scale ranging from 0, poor, to 4, excellent. Items rated were number of mental health doctors, location of mental health doctors, range of mental health services, and quality of mental health care.

Seventy-six percent of the respondents were female, and 95 percent were white. Their average age was 41.7 years. Although 62 percent had a college degree, only 47 percent were working.

Eighty-five percent of the respondents had gatekeepers who restricted their access to provider networks, and these individuals were less satisfied with their health plan (Figure 1). This finding is important because studies indicate that dissatisfaction influences insurance disenrollment, creates problems in adherence, and promotes changes in providers (1). It also may account for a drop in treatment rates among bipolar disorder patients in managed care (2). Thus in these new systems of care, special attention to tracking services and satisfaction over time may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Stanley Center for the Innovative Treatment of Bipolar Disorder, the Stanley Foundation, and National Institute of Mental Health grant MH-30915.

The authors are affiliated with the departments of psychiatry, pediatrics, and health services in the School of Medicine and the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Harold A. Pincus, M.D., and Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are coeditors of this column.

Figure 1. Satisfaction ratings of privately insured persons with bipolar disorder (N=370) with the mental health services provided by their health care plan, by type of gatekeeping and network restrictions

1 Ratings range from 0, poor, to 4, excellent.

1. Strasser S, Aharony L, Greenberger D: The patient satisfaction process: moving toward a comprehensive model. Medical Care Review 50:219-248, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Johnson RE, McFarland BH: Lithium use and discontinuation in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:993-1000, 1996Link, Google Scholar