HIV Risk Factors Among People With Severe Mental Illness in Urban and Rural Areas

Abstract

No studies have reported HIV risk behavior in rural populations with severe mental illness. A total of 84 rural patients with severe mental illness in New Hampshire and 158 urban patients in Baltimore were interviewed about their HIV risk behavior in the past six months using the Risk Assessment Battery, a 38-item structured clinical interview. Rates of sexual and drug risk behavior among rural patients were significantly lower than among urban patients. Regression analyses showed that urban setting, younger age, never having been married, and a bisexual or gay orientation significantly predicted higher HIV risk scores. The differences in risk behaviors may reflect urban-rural differences in drug availability and sexual practices.

Studies have found elevated rates of HIV infection among people with severe mental illness (1) and any mental disorder (3) compared with rates in the general population (2). Urban studies also indicate that people with severe mental illness have high rates of HIV risk behaviors (4). To our knowledge, no studies have reported HIV risk behaviors in people with severe mental illness in rural or small metropolitan areas, where sexual and drug use practices may be different than in urban locations.

Urban-rural differences in HIV risk behaviors among people who are not severely mentally ill support the hypothesis that such differences will be found in persons with severe mental illness. Geographic differences in substance abuse may affect HIV risk because rural rates of illicit drug use are lower (5). In addition, sources of HIV infection vary regionally. Although people in rural areas report less frequent sexual HIV risk behaviors in general (6), they are more likely to contract HIV through sexual behaviors, whereas people in urban areas are more likely to contract HIV through intravenous drug use (7).

This paper reports a cross-sectional study of the prevalence of self-reported HIV risk factors and self-reported HIV infection among patients with severe mental illness in New Hampshire and Baltimore. For the purpose of this report, we refer to the Baltimore study sites as urban and the New Hampshire study sites as rural even though the New Hampshire sites included small metropolitan as well as rural areas. We hypothesized that rural patients would report lower rates of drug risk behaviors, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV infection than urban patients.

Methods

Patients in this study were part of a larger study assessing environmental risks, safety, and health practices among people with severe mental illness (8). The study was conducted in New Hampshire and Baltimore with a convenience sample of patients who were receiving public-sector psychiatric services.

Inclusion criteria were age between 18 and 60 years, receipt of public-sector treatment for severe and persistent mental illness, and ability to provide informed consent. Approximately 10 percent of the patients who were approached to participate in the assessments declined.

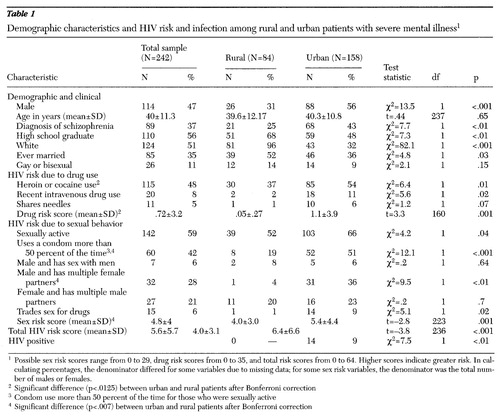

Table 1 presents demographic information about the 158 urban patients and the 84 rural patients in the study.

Patients who met inclusion criteria were asked by their clinicians or researchers to participate in the study. Trained interviewers administered a standardized assessment between January and September 1996. All participants gave written informed consent.

Psychiatric diagnoses were based on chart records, except for the 52 patients assessed at New Hampshire Hospital (19 percent of the total sample), where diagnoses were previously determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (9). Demographic data were obtained from patients' charts. HIV risk behaviors for the past six months and related information were assessed using the Risk Assessment Battery (10), a 38-item structured clinical interview. Responses to seven questions about drug risk and nine questions about sex risk were compiled into drug and sex subscores and then summed into a total risk score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 64.

We performed chi square tests for dichotomous variables and t tests for continuous variables. When possible, skewed continuous variables were converted to dichotomous variables. Stepwise linear regressions were performed to explore the relationship between urban or rural location and HIV risk.

Results

HIV status and risk factors for the two study groups are reported in Table 1. None of the 84 rural patients reported they were HIV positive, although 51 (61 percent) reported they had been tested. Fourteen (9 percent) of the urban patients reported they were HIV positive, and 120 (76 percent) reported they had been tested.

The mean scores for HIV risk due to sexual behavior (sex risk), HIV risk due to intravenous drug use (drug risk), and total HIV risk were significantly lower in the rural group than in the urban group. Because the main dependent variable, total HIV risk score, was skewed, further analyses used a log transformation of the risk score.

The significant difference in mean HIV risk score between patients in the two states might have been related to diagnostic and demographic differences. We therefore carried out t tests of the differences in HIV risk scores for the demographic factors of concern, as well as a series of stepwise regressions using the log transformation of total risk score as the dependent variable and gender, age, marital status, education, sexual orientation, diagnosis, and urban-rural location as independent variables. The t tests indicated no difference in mean HIV risk scores between men and women, between those with and without a high school education, between those who had ever been married versus those who had never been married, and between those with and without psychotic disorders. The mean HIV risk score for nonwhite patients was higher than that for white patients (1.7 and 1.5, respectively; t=2.27, df=186, p=.03).

In the first regression analysis, urban location, younger age, never having been married, and bisexual or gay orientation entered as significant predictors of high HIV risk score, with p values less than .05 and betas of .23, -.24, .15, and .24, respectively. These factors accounted for 13 percent of the variability in risk score, and the equation was highly significant (adjusted R2=.13; F=10.11, df=4,237, p<.001). Gender, education, race, and diagnosis were not significant predictors of high HIV risk when other factors were controlled.

Because the urban study group was predominately African American and a small but statistically significant difference was found in HIV risk score between whites and nonwhites, we performed a separate regression analysis on data from the white patients in both settings to confirm rural-urban differences in HIV risk score. Urban location and bisexual or gay orientation again predicted a higher HIV risk score (adjusted R2=.06; F=4.65, df=2,122, p=.01). Both predictor variables had p values less than .04, and betas of .18 and .23, respectively.

Discussion and conclusions

In this preliminary study of HIV risk in people with severe mental illness, rural patients in New Hampshire reported fewer sexual and drug-related HIV risk behaviors in the past six months and a lower prevalence of HIV infection than urban patients in Baltimore and other urban groups in previous reports (4). Because differences by location in gender, diagnosis, education, marital status, and race could account for the differences in HIV risk score, we used t tests and regression analyses to show that these factors were unlikely to be confounders.

Thus urban setting appears to be independently related to HIV risk and may be a proxy for factors such as drug availability or culturally defined sexual practices that affect risk status. That is, the use of intravenous drugs and crack cocaine, which is more common in urban areas, has been correlated with high-risk sexual behaviors as well as with HIV infection.

Our study has several limitations. First, because our study groups were region-specific convenience samples, our findings may not be generalizable to other rural or urban patients. Second, the validity of self-reports of sexual behavior is difficult to assess, but all studies of HIV risk have relied on self-report due to the difficulty in directly observing sex and drug behaviors. Third, the rural and urban groups were significantly different in demographic factors, all of which could relate to HIV risk behaviors. We used statistical techniques to control for these differences. Underlying culturally based attitudes and beliefs not measured in this study could be related to geographic differences in HIV risk behaviors. Future studies should use randomly selected patients from community mental health populations in adjacent rural and urban areas to address these problems and test the validity of our findings.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants MH-56147and MH-00839 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Except for Dr. Goodman and Dr. Osher, the authors are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center and with the department of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School. Dr. Goodman is with the department of psychology at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, and Dr. Osher is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Send correspondence to Dr. Brunette at the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, State Office Park South, 105 Pleasant Street, Concord, New Hampshire, 03301 (e-mail, mary.f. [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics and HIV risk and infection among rural and urban patients with severe mental illness1

1 Possible sex risk scores range from 0 to 29, drug risk scores from 0 to 35, and total risk scores from 0 to 64. Higher scores indicate greater risk. In calculating percentages, the denominator differed for some variables due to missing data; for some sex risk variables, the denominator was the total number of males or females.

2 Significant difference (p<.0125) between urban and rural patients after Bonferroni correction

3 Condom use more than 50 percent of the time for those who were sexually active

4 Significant difference (p<.007) between urban and rural patients after Bonferroni correction

1. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:259-269, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Karon JM, Rosenberg PS, McQuillan G, et al: Prevalence of HIV infection in the United States, 1984-1992. JAMA 276:126-131, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hoff RA, Beam-Goulet J, Rosenheck RA: Mental disorder as a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus infection in a sample of veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:556-560, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carey MP, Carey KB, Kalichman SC: Risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clinical Psychology Review 17:271-291, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Blazer D, George LK, Landerman R, et al: Psychiatric disorders: a rural/urban comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:651-656, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Scheidt DM, Windle M: The alcoholics in treatment HIV risk (ATRISK) study: gender, ethnic, and geographic group comparisons. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 56:300-308, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wasser SC, Gwinn M, Fleming P: Urban-nonurban distribution of HIV infection in childbearing women in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 6:1035-1042, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mueser KT, Goodman L, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493-499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV: Axis I Disorders—Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

10. Metzger DS: The Risk Assessment Battery (RAB): validity and reliability. Presented at the annual meeting of the National Cooperative Vaccine Development Group for AIDS. Oct 30-Nov 4, 1993Google Scholar