Two-Year Outcomes of Psychosocial Rehabilitation of Black Patients With Chronic Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Outcome as measured by psychosocial functioning was examined in a two-year follow-up study of 46 patients with chronic mental illness, 44 of whom were African American, who participated in an intensive psychosocial rehabilitation program based in a community mental health center. METHODS: Patients attended a program that operated seven days a week in a predominantly urban, black section of Baltimore. Level of functioning was determined at baseline and at six and 12 months using a scale based on data from the 1972 International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Parameters assessed included the length of time patients stayed out of the hospital, the frequency and depth of social relationships, dysfunction in work, the presence of symptoms, the ability to maintain personal hygiene, and the ability to participate in leisure activities. RESULTS: The sample was divided into three diagnostic groups: patients with schizophrenia alone (N=27), patients with a mood disorder (N=12), and patients with a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and a substance use disorder (N=7). Scores on the level-of-functioning measure were significantly correlated between baseline and six months, between six months and 24 months, and between baseline and 24 months. Statistical tests indicated a substantial and significant increase in level of functioning from baseline to 24 months for all groups. CONCLUSIONS: The results provide evidence for the effectiveness of an intensive psychosocial rehabilitation program for urban, black patients with chronic psychiatric illness, including those with a dual diagnosis.

The literature on the black, chronic mentally ill population is not extensive (1,2,3). One focus has been on issues of psychiatric diagnosis and misdiagnosis (4,5,6,7,8,9). Another concern has been the use and dosage level of antipsychotic medication (10). Although psychosocial interventions have been found to be effective for people with chronic mental illness (11,12,13,14), outcomes of such programs for black, chronic mentally ill patients have not been studied extensively.

Recently, treatment of patients with a comorbid psychotic illness and a substance use disorder—a dual diagnosis—has received increasing attention (15,16,17,18,19). For example, Lehman and associates (20) showed that homeless persons with a dual diagnosis benefited over a 12-month period from an assertive community treatment program, accruing fewer inpatient days, fewer emergency room visits, and more outpatient psychiatric visits.

Programs that combine intensive case management and substance abuse treatment services, such as relapse prevention, education about substance misuse, and motivational interviewing, along with 12-patient caseloads and 24-hour responsibilities by team members, have been found to be effective (21). After two years in such a program, patients' drug- and alcohol-related symptoms improved, and their service utilization decreased; a trend toward better social adjustment was also noted (22,23).

This paper describes the outcome of a two-year follow-up of 46 patients, most of whom were African American. The patients had chronic mental illness and participated in an intensive psychosocial rehabilitation program based in a community mental health center located in a predominantly urban, black community in Baltimore, Maryland. The investigators asked four questions. Did the patients' level of function change over time? Did patients in particular diagnostic groups benefit more from the program? Was length of time of participation in the program correlated with improvement? Were patients with dual diagnoses able to obtain any benefit from the program?

Methods

The psychosocial rehabilitation program

To address the needs of its chronic mentally ill population, a community mental health center in a predominantly African-American section of Baltimore established a psychosocial rehabilitation program in 1990 based on the assertive community treatment model (24,25). Psychiatric patients with at least a three-year history of mental illness who had minimal social skills, poor personal habits, poor compliance with treatment, or no social network were eligible for admission to the program.

The program operated seven days a week and provided transportation via a van to the program site. The program began each day with the preparation of a full breakfast by program participants supervised by staff. The program continued with an hourly schedule of classes that included instruction in personal grooming, housekeeping skills, cooking, office skills, computer skills, adult education topics, and vocational rehabilitation tailored to the specific needs of each participant. Lunch and a snack were prepared and served, and the area was cleaned by program participants supervised by staff. At the end of the program's six-hour day, participants were transported home.

On weekends participants were transported to the site for group meetings to review and complete plans for weekend activities such as bowling, going to movies and museums, and attending church services. On Saturday evening participants were transported to the program's social club, called Mock Tails, for an evening of socialization with nonalcoholic drinks. Participation in all weekend activities was voluntary.

While in the program, participants continued in their outpatient therapy. Each patient's case manager and therapist worked together closely to monitor the patient's attendance in the program and involvement in outpatient therapy. Each case manager was responsible for approximately ten to 12 patients. The program team for each participant consisted of a case manager, a patient advocate, and a psychiatrist. The site of outpatient treatment for the majority of patients was at the community mental health center, which was five blocks away from the program site.

Participants were referred to the program from the inpatient units of the community mental health center and by outpatient therapists in the catchment area. Participants could remain in the program as long as they met eligibility requirements and demonstrated a potential for benefiting from the program. The length of stay varied depending on the type of illness, the presence of a comorbid substance use disorder, compliance with treatment, and frequency of hospitalization. The average length of stay for a patient with a schizophrenic illness was two years. For a patient with schizophrenia who also had a diagnosis of abuse of or dependence on cocaine, heroine, alcohol, or marijuana, the average length of stay was three and a half years.

Sample characteristics

All patients in treatment in the psychosocial rehabilitation program in 1993 were eligible to participate in the study. Informed consent was obtained, and patients' baseline level of psychosocial functioning was determined with a modified version of a 14-item scale of predictors of the outcome of schizophrenia. The scale assessing level of functioning, which was first described by Strauss and Carpenter in 1972 (26), was developed based on data from the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia.

Of the 76 eligible patients, 29 were discharged before the two-year study ended, resulting in a sample of 47 subjects. The major reasons for discharge were treatment dropout, uncontrolled cocaine dependence, and change of residence. In addition, some patients could not be located for follow-up interviews.

The age, sex, race, and marital status of the 29 discharged patients and the 47 patients who were still in treatment at the 24-month follow-up were not statistically different. During the study period, none of the participating patients were changed from a traditional antipsychotic to a new atypical antipsychotic, and only two patients were rehospitalized, one for an exacerbation of psychosis and one for the removal of a meningioma.

The first author evaluated participants at baseline in 1993, at a six-month follow-up in 1994, and at 24 months in 1995. Demographic information was obtained at baseline, and a DSM-III-R checklist (27) was completed to establish specific diagnoses based on DSM-III-R criteria and the author's previous experience with this population (4,5,6,7,8,9,28).

A modified version of the instrument to measure patients' level of psychosocial functioning (26) was used at all three time points. Among other things, the scale assesses the length of time a patient remains out of the hospital, the frequency and depth of social relationships, dysfunction in work, the presence of symptoms, the ability to maintain personal hygiene, and the ability to participate in leisure activities. The scale has been used to assess patients with chronic mental illness; ratings from 0 to 4 are given, with ratings of 0 and 1 indicating continuous or severe impairment, 2 and 3 moderate impairment, and 4 no impairment.

Results

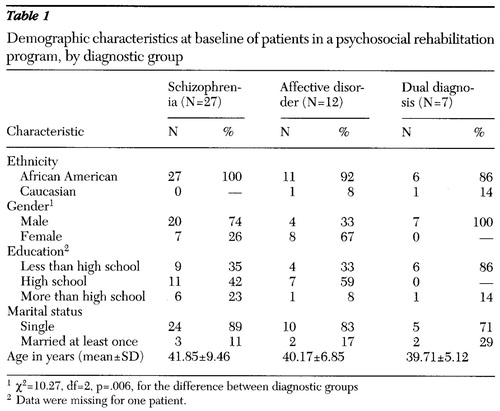

One subject, who did not meet criteria for one of the three diagnostic groups derived for the study, was not included in the analysis. Table 1 presents demographic data for the remaining 46 subjects. Twenty-seven patients (59 percent) had schizophrenia, 12 patients (26 percent) had an affective disorder (major depression, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or dysthymia), and seven patients (15 percent) had a dual diagnosis of schizophrenia and a substance use disorder involving alcohol, heroin, or cocaine, or polysubstance use.

Forty-four patients (96 percent) were African American, and the remaining two patients were Caucasian. The participants tended to be single men with a high school education. The mean age for all three groups was around 40 years. Chi square tests for gender differences between diagnostic groups indicated that the group of patients with schizophrenia and the dual diagnosis group had significantly higher proportions of men than women, whereas the group with an affective disorder had a significantly higher proportion of women than men.

The association between patients' scores on the measure of functioning and the demographic variables of gender and education were assessed by analysis of variance (ANOVA); the association with age was assessed by correlation. None of the relationships were statistically significant, and these variables were not investigated further. Correlations between scores at baseline, six months, and 24 months were all statistically significant. The correlation between the baseline and six-month functional-level score, which was assessed for 33 patients, was .51 (p<.003). The correlation between the six-month and 24-month scores, assessed for 35 patients, was .52 (p=.001). The correlation between the baseline score and the 24-month score, assessed for 42 patients, was .33 (p=.031).

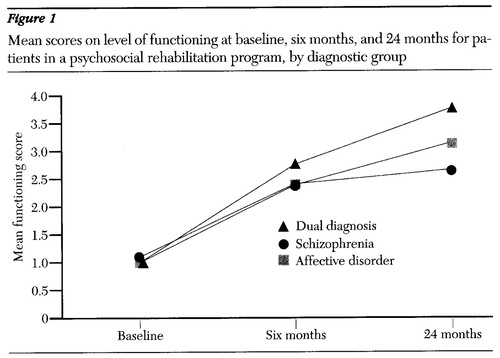

Figure 1 presents the findings for level of functioning for the three groups at baseline and the two follow-up points. For the 20 patients in the schizophrenia group, the mean±SD scores were 1.10±.45 at baseline, 2.40±1.19 at six months, 2.65±1.46 at 24 months, and 2.05±1.29 for the overall study period. For the group of eight patients with affective disorders, these values were 1±0, 2.38± .92, 3.13±.99, and 2.17±1.17, respectively. For the four patients in the dual diagnosis group, the scores were 1±.82, 2.75±1.50, 3.75±.50, and 2.50±1.51, respectively. For all three groups combined (N=32) the mean±SD scores were 1.06±.44 at baseline, 2.44±1.13 at six months, 2.91±1.30 at 24 months, and 2.14±1.29 overall.

With one nested factor (diagnostic group) and one repeated measure (time period), the overall ANOVA model accounted for a significant amount of the variance in level of functioning—40.6 percent (F=7.43, df=8,87, p<.001). The main effect of group and the interaction between group and time period were not statistically significant. The main effect of time period was significant, with an increase in the level-of-functioning scores across the three time periods (F=41.29, df=2,58, p<.001).

To address possible violations of the assumptions of repeated-measures ANOVA designs, such as sphericity, the Geisser-Greenhouse correction was used (29). This correction decreases the degrees of freedom, which, in turn, increases the critical F value needed to reach statistical significance under the premise that maximum violation occurred. Therefore, this is a conservative modification. With this adjustment, the new critical F value (df=1,31) was 4.17 for a p value of .05, 7.56 for a p value of .01, and 13.3 for a p value of .001. Therefore, both the F value of 7.43 for the overall model and the F value of 41.29 for the main effect of time period (repeated measures) remained statistically significant even with this conservative correction.

A Newman-Keuls subsequent test was performed on the three pairwise comparisons. The critical mean difference between baseline and six months needed to indicate significance was .403 and the actual critical mean difference was 1.38; between six and 24 months, the needed difference was .403 and the actual difference was .47; and between baseline and 24 months, the needed difference was .484, and the actual difference was 1.85. Each of the comparisons was significant, indicating a substantial increase in scores from baseline to six months, from six months to 24 months, and from baseline to 24 months.

Figure 1 appears to indicate that patients in the dual diagnosis group and the group with affective disorders made more progress over time than the patients with schizophrenia. However, the relatively small size of the sample may have resulted in a lack of statistical power. Extrapolating from the results of this study, it was estimated that a sample size twice as large for each group would have been needed for the group-by-time period interaction to achieve significance. Based on the observed data, such an increase in sample size could demonstrate significant group-by-time interaction with a large change between groups in functioning level over time.

Discussion and conclusions

The assertive community treatment model (24,25) has been successfully applied in a variety of settings (30,31), among homeless mentally ill persons (32), and among patients with chronic mental illness and substance use disorders (18,19,33,34).

The study reported here is limited by the small sample size—46 patients in the total sample, with 24-month data for 32 patients. However, it is one of the few longitudinal studies of patients with chronic mental illness that has focused on a sample in which most patients were African American. Most patients in the study were young African-American men with a history of unskilled employment and at least a high school education who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; some had a comorbid substance use disorder. The African-American women in the sample with schizophrenia were more likely to have a comorbid affective disorder. The findings were consistent with the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the age cohorts represented (35).

The participants were drawn from a community mental health center serving a specific catchment area. Thus the results are applicable to cities the size of Baltimore that have an African-American population of 50 percent or greater. Investigators interested in replicating this study are encouraged to ensure that the rater is blind to the study objectives and to establish interrater reliability if more than one rater is used to assess subjects.

Parameters assessed by the level-of-functioning measure included the length of time patients stayed out of the hospital, the frequency and depth of social relationships, dysfunction in work, the presence of symptoms, the ability to maintain personal hygiene, and the ability to participate in leisure activities (26). In this sample of 32 black patients with chronic mental illness who completed 24 months of a psychosocial rehabilitation program, a statistically significant improvement was found in these parameters; the four patients with a dual diagnosis who remained in the program at 24 months also showed improvements. Although some patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia continued to have a restricted social network, all participants showed significant improvement in treatment compliance due to the structure of the program. The hospitalization rate decreased—only one patient had a psychiatric hospitalization during the study period. These findings are similar to those reported by previous studies of persons with chronic mental illness (12,13,14,17,20,21,33).

The seven patients with a dual diagnosis at baseline had a history of remissions and relapses resulting in hospitalization for treatment of exacerbated psychotic illness. The program's aggressive outreach, assertive case management (18,21,31), and daily monitoring (16,17,18,19,21,3333) may have enabled these patients to maintain abstinence and to resolve their acute psychoses, which may have been exacerbated by their substance abuse.

In the mental health care system, the current emphasis is on decreasing inpatient days and implementing treatment in outpatient settings (36,37), particularly for patients with schizophrenic illness (38). The limited results of this study suggest that the psychosocial rehabilitation program may be a cost-effective model for the management of African-American patients with chronic mental illness, including those with an additional diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence.

Acknowledgment

Dr. Hishinuma collaborated in this study with the support of the native Hawaiian mental health research development program sponsored by the department of psychiatry at the Johns A. Burns School of Medicine of the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Dr. Baker is professor and Dr. Hishinuma is assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at the John A. Burns School of Medicine of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Ms. Stokes-Thompson is director of the new phases program and Ms. Gonzo is a case manager in the program at the Community Institute of Behavioral Services in Baltimore. Dr. Davis is associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Send correspondence to Dr. Baker at Hawaii State Hospital, 45-710 Keaahala Road, Kaneohe, Hawaii 96744-3597.

Figure 1. Mean scores on level of functioning at baseline, six months, and 24 months for patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program, by diagnostic group

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics at baseline of patients in a psychosocial rehabilitation program, by diagnostic group

1 χ2=10.27, df=2, p=.006, for the difference between diagnostic groups

2 Data were missing for one patient.

1. Kramer M, Rosen M, Wilis EM: Definition and distribution of mental disorders in a racist society, in Racism and Mental Health. Edited by Kramer BM, Brown BS. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1973Google Scholar

2. Lawson WB: Chronic mental illness and the black family. American Journal of Social Psychiatry 6:57-61, 1986Google Scholar

3. Wilkinson CB, Spurlock J: The mental health of black Americans: psychiatric diagnosis and treatment, in Ethnic Psychiatry. Edited by Wilkerson CB. New York, Plenum, 1986Google Scholar

4. Bell C, Mehta H: The misdiagnosis of black patients with manic-depressive illness. Journal of the National Medical Association 72:141-145, 1979Google Scholar

5. Bell CC, Thompson JP, Lewis D, et al: Misdiagnosis of alcohol-related organic brain syndromes: implications for treatment, in Treatment of Black Alcoholics. Edited by Brisbane FL, Womble M. New York, Haworth, 1985Google Scholar

6. Jones BE, Gray BA, Parson EB: Manic-depressive illness among poor urban blacks. American Journal of Psychiatry 185:654-657, 1981Google Scholar

7. Adebimpe VR: Overview: white norms and psychiatric diagnosis of black patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:279-285, 1981Link, Google Scholar

8. Adebimpe VR: Hallucinations and delusions in black psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 73:517-520, 1981Medline, Google Scholar

9. Coleman D, Baker FM: Misdiagnosis of schizophrenia among older black veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:527-528, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sunderland TL, Ranganath V, Lin K-M, et al: Psychopharmacologic considerations in the treatment of black American populations. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 27:441-448, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

11. Scott JE, Dixon LB: Psychological interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:621-630, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Prendergast PJ: Integration of psychiatric rehabilitation in the long-term management of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 40(suppl 1):S18-S21, 1995Google Scholar

13. Penn DL, Mueser KT: Research update on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:607-617, 1996Link, Google Scholar

14. Campo DD, Wolcott PA, Mize TI, et al: Approaches to psychosocial rehabilitation. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 4:328-333, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Corty E: Assessment and classification of patients with psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1019-1025, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Substance abuse among the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1041-1046, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Drake RE, Bartels SJ, Teague GB, et al: Treatment of substance abuse in severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:606-611, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kline J, Harris M, Bebout RR, et al: Contrasting integrated and linkage models of treatment for homeless dually diagnosed adults. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 50:95-105, 1991Google Scholar

19. Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, et al: Service utilization and costs associated with substance use disorder among severely mentally ill patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:227-232, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:1038-1043, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Johnson S: Dual diagnosis of severe mental illness and substance misuse: a case for specialist services? British Journal of Psychiatry 171:205-208, 1997Google Scholar

22. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Noorsdy DL: Treatment of alcoholism among schizophrenic outpatients:4-year outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:328-329, 1993Google Scholar

23. Drake RE, Mueser KT, Clark RE, et al: The course, treatment, and outcome of substance disorder in persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:42-51, 1996.Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to the hospital: a controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 132:517-522, 1975Link, Google Scholar

25. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternatives to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:739-746, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

28. Baker FM: Misdiagnosis among older psychiatric patients. Journal of the National Medical Association 87:872-876, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

29. Keppel G: Design and Analysis: A Researcher's Handbook, 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1991Google Scholar

30. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Link, Google Scholar

31. Bond GR, Miller LD, Krumwied RED, et al: Assertive case management in three CMHCs: a controlled study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:411-418, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Dixon LB, Krauss N, Kernan E, et al: Modifying the PACT model to serve homeless persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:682-688, 1995Google Scholar

33. Teague GB, Drake RE, Ackerson TH: Evaluating use of continuous treatment teams for persons with mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 46:689-695, 1995Link, Google Scholar

34. Ridgely MS, Lambert D, Goodman A, et al: Interagency collaboration in services for people with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorder. Psychiatric Services 490:236-238, 1998Link, Google Scholar

35. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, Grebb JA: Schizophrenia, in Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry, Behavioral Sciences, Clinical Psychiatry, 7th ed. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1994Google Scholar

36. Warner R, Huxley P: Outcome for people with schizophrenia before and after Medicaid capitation at a community agency in Colorado. Psychiatric Services 49:802-807, 1998Link, Google Scholar

37. Smith TE, Docherty JP: Standards of care and clinical algorithms for treating schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:203-220, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Lehman AF: Public health policy, community services, and outcomes for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:221-231, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar