Are Sex Offenders Treatable? A Research Overview

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Recent legislation in several states providing for civil commitment and preventive detention of sexually violent persons has stirred legal, clinical, and public policy controversies. The mandate for psychiatric evaluation and treatment has an impact on public mental health systems, requiring clinicians and public administrators to direct attention to treatment options. It is a common view that no treatments work for disorders involving sexual aggression. The authors examine this assumption by reviewing research on the effectiveness of treatment for adult male sex offenders. METHODS: MEDLINE was searched for key reviews and papers published during the years 1970 through 1998 that presented outcome data for sex offenders in treatment programs, individual case reports, and other clinically and theoretically important information. RESULTS: Although rigorous research designs are difficult to achieve, studies comparing treated and untreated sex offenders have been done. Measurement of outcome is flawed, with recidivism rates underestimating actual recurrence of the pathological behavior. Outcome research suggests a reduction in recidivism of 30 percent over seven years, with comparable effectiveness for hormonal and cognitive-behavioral treatments. Institutionally based treatment is associated with poorer outcome than outpatient treatment, and the nature of the offender's criminal record is an important prognostic factor. CONCLUSIONS: Although treatment does not eliminate sexual crime, research supports the view that treatment can decrease sex offense and protect potential victims. However, given the limitations in scientific knowledge and accuracy of outcome data, as well as the potential high human costs of prognostic uncertainty, any commitment to a social project substituting treatment for imprisonment of sexual aggressors must be accompanied by vigorous research.

Few issues in the mental health field are capable of stirring more controversy than the psychiatric treatment of sex offenders. Recent legislation in a growing number of states providing for civil commitment and preventive detention of sexually violent persons (1,2) has fueled long-standing debates on the diagnosis of paraphilias, the nature of mental illness, and the treatability of sex offenders (3).

Regarding treatment, a body of literature has evolved steadily over the past two decades that addresses the effectiveness of treatment programs for sex offenders, but it remains specialized and unfamiliar to many general psychiatrists (4,5,6,7). It is commonly assumed, and even argued in support of public policy, that disorders involving aggressive sexual behaviors are unlike other mental illnesses because they are untreatable. The purpose of this paper is to examine this assumption more closely by reviewing the research on the effectiveness of treatment for sex offenders, focusing primarily on adult males.

Methods

A MEDLINE search covering the years 1970 through 1998 was done to identify key reviews and papers presenting data on outcomes for sex offenders in treatment programs, individual case reports, and other clinically and theoretically important information.

Background

Recent research has suggested that more than half of all women and one-fifth of all men in the United States will be sexually assaulted at some point. One study estimated that by the time rapists enter treatment, they had assaulted an average of seven victims and that nonincestuous pedophiles who molest boys had committed an average of 282 offenses against 150 victims (8). The impact of these offenses on their victims can be devastating. The number of sex offenders in state prisons has increased by more than two-thirds in the last decade, leading to increasing burdens on public budgets (9). The number of treatment programs has grown, although some programs have closed due to limited funds (9).

Identified on the basis of sexual behavior sufficiently aberrant and aggressive to bring the perpetrator to the attention of law enforcement officials, sex offenders as a group include a variety of types of individuals. Although it has been suggested that the vast majority of rapists have no mental disorder other than antisocial personality disorder (3), many offenders meet diagnostic criteria for paraphilias, especially pedophilia, and may also suffer from comorbid anxiety, depressive, or psychotic disorders.

Some treatment programs have attempted to assess the outcomes of their interventions. However, little is definitively known about the efficacy of many of the treatments currently in use, and research necessary to produce such knowledge must confront particularly difficult problems. Before discussing the nature of sex offender treatment and its outcome, we will review the major difficulties this type of research must face.

Problems in sex offender research

Assessment

One of the most difficult issues in the treatment of sex offenders is how to measure improvement. Investigators have not identified a standardized measurement technique that they agree can reliably and validly measure the frequency of sex offenses.

Sex offenders' self-reports or significant others' reports are not reliable indexes of recidivism (10,11). Arrest records underreport sexual offenses (5,12,13); the vast majority of sexual offenses, estimated at greater than 93 percent, are never reported to the police, and fewer than 1 percent of sex offenders are arrested (14). Even fewer are convicted. Arrest and conviction records are also affected by administrative policies that determine which subjects are hospitalized rather than incarcerated. Furthermore, many sex offenders plea bargain—that is, they plead guilty to lesser charges of crimes that are not sexual offenses.

Some researchers have attempted to answer the problem of assessment by studying patterns of sexual response via penile plethysmography, which measures penile erectile responses to stimuli in the laboratory. Proponents have argued that plethysmography can identify rapists and can differentiate those with the most victims and those who show sadistic behavior (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22). Plethysmography has been successful in identifying child molesters, and in differentiating offenders who use excessive force in their assaults (23,24,25).

However, the reliability, validity, and appropriate uses of plethysmography are the subject of debate. There is a lack of reliability between the different types and models of plethysmographs in use (26). Methods for selecting and presenting stimuli and for interpreting plethysmographic data also differ. Regarding validity, it is not known to what extent treatments that inhibit sexual response during plethysmography actually prevent sexual aggression in the community. Some studies have shown relationships between posttreatment deviant arousal on plethysmography and subsequent recidivism (27,28,29,30), but other studies have reported no such relationships (10,31). Furthermore, some men who are sexually aroused by images of children are not sex offenders (32,33). Many subjects can voluntarily suppress or produce erections in the laboratory (34). Subjects may suppress responses to the extent that the test is not helpful (26).

In general, plethysmography is useful in identifying individuals with high levels of inappropriate arousal and low levels of appropriate arousal (22,35). Plethysmography can be a helpful adjunct to treatment in that deviant arousal patterns can be used to confront offenders who deny deviant sexual interests. However, many professionals believe that plethysmography should not be used to predict further acts of sexual offense and should not be used to confirm or deny allegations of such behavior (36).

Study design

Besides difficulties in assessment, research involving sex offenders faces problems in research design. One important factor is whether the study design compares treated and untreated samples of sex offenders. The ideal design would involve matching patients on important variables and then randomly assigning them to groups that received treatment and groups that did not. However, because of ethical issues, this design is rarely achieved.

Sampling

Another problem is which patients are studied, because many variables other than treatment may affect outcome—for example, presence of deviant sexual arousal, occurrence of sexual intercourse during the assault, number of victims, IQ, and socioeconomic status (27,37).

Program selection criteria also affect results. Some treatment programs select only patients fitting a given profile, such as low-risk offenders. The use of differential selection criteria by various treatment programs makes it difficult to draw conclusions across studies.

Which types of offenders are considered together in study groups is also important. For example, research suggests that incest offenders recidivate at approximately half the rate of extrafamilial child molesters (10). Among extrafamilial child molesters, those who molest girls or boys or both should be differentiated (10,38).

In addition to affecting outcome results, sampling techniques define and limit a study's generalizability. Many studies report on small samples and thus are vulnerable to the bias that positive results are more likely to be published than negative results. Other studies are limited to subjects who comply with treatment. Given the large dropout rates of many treatments, this practice exerts a sampling bias in favor of positive results.

Follow-up and recidivism

Duration of the study follow-up period is another source of variability between studies. Longer follow-up periods generally produce higher recidivism rates (10,28,39). Several studies have suggested that even a five-year period of risk for reoffense is not long enough (28). One extremely long-term study indicated that approximately 19 percent of a large sample of child molesters were reconvicted more than ten years after release, and some reconvictions occurred after more than 31 years (39).

The definition of recidivism is also important. Most studies assess subjects as having recidivated if they are arrested or convicted of a further sex offense after treatment, but other studies use arrest or conviction of a crime of any type or violation of probation or parole. This issue is important because sex offenders may plea bargain to reduce their crimes to those of a nonsexual nature. Adding to the complexity, some studies fail to specify their definition of recidivism.

Somatic therapies

This section reviews research on somatic therapies for adult male sex offenders. Several surgical and medical treatments not frequently used today are described briefly. Next, we provide a more extensive discussion of antiandrogen treatments for sex offenders, including two tables summarizing the relevant studies. Antiandrogen treatment is the most successful direction for biological treatment to date. Finally, we review other hormonal and serotonergic agents, relatively new medications that may be promising in the treatment of sex offenders.

Surgical treatments

Surgical treatments for sex offenders are of two general types: neurosurgery and castration. The neurosurgical procedure, stereotaxic hypothalamotomy, involves removal of parts of the hypothalamus to disrupt production of male hormones and decrease sexual arousal and impulsive behaviors. However, the neuroendocrine mechanisms involved are not well understood, and the procedure has shown a significant failure rate and adverse sequelae.

For primarily ethical reasons, surgical castration has not been widely advocated as a treatment for sex offenders, and in some countries such treatment is illegal. Castration has been shown to be highly effective in European literature. For example, Cornu (40) reported that among a group of sex offenders followed for periods of five to 30 years, those who had accepted the option of castration had recidivism rates of 5.8 percent compared with 52 percent for those who refused castration. Recidivism rates have been reported to decrease over time following the procedure, which may be related to the rate of decline of testosterone levels following the procedure (41). Such a finding, if substantiated, might contribute an empirical basis for determining clinically indicated lengths of hospitalization or institutional confinement following surgery.

Favorable reports on castration have been countered by reviews in which it has been disparaged on ethical grounds and scientifically discredited as not 100 percent effective. With the advent of sexual predator laws, castration as a treatment option is now subject to discussion that includes media attention to individual cases as well as focused state legislation specifying the conditions under which orchiectomy may be performed. Recent legislation permitting voluntary orchiectomy in Texas was coupled with a requirement for follow-up research on recidivism (42).

Medical treatments

Before the more widespread use of antiandrogens in the treatment of sex offenders, clinicians attempted treatment with oral and implantable estrogens (43) and with an estrogen analogue, diethylstilbesterol (44). In general, research findings agree that the potential for adverse effects limits the utility of estrogen treatment for sex offenders (45).

A number of early studies reported on the treatment of sex offenders with neuroleptics (46,47,48). However, these agents were found to be of limited benefit, which did not outweigh the risk of tardive dyskinesia. Antipsychotic agents may benefit sex offenders with comorbid psychotic disorders, especially patients who are receiving hormonal therapy, which may exacerbate psychosis (45). The advent of newer, atypical antipsychotic medications may warrant a reassessment of therapeutic effects and side-effect risks associated with these medications.

Antiandrogen medications

Among the most important biological advancements is the use of antiandrogen medications. The two most widely used forms are medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), available in the United States, and cyproterone acetate (CPA), available in Canada and Europe. Both are synthetic progesterones that reduce the serum level of circulating testosterone, with concomitant reductions in sex offenders of self-reported deviant sexual fantasies and behaviors (49,50). Reduction of testosterone has been shown to reduce libido, erections, ejaculations, and spermatogenesis (51). A library search covering the past 20 years found more than 30 papers reporting the effectiveness of antiandrogens in reducing testosterone levels for sex offenders, along with decreased self-reported deviant sexual drive, fantasy, and behavior.

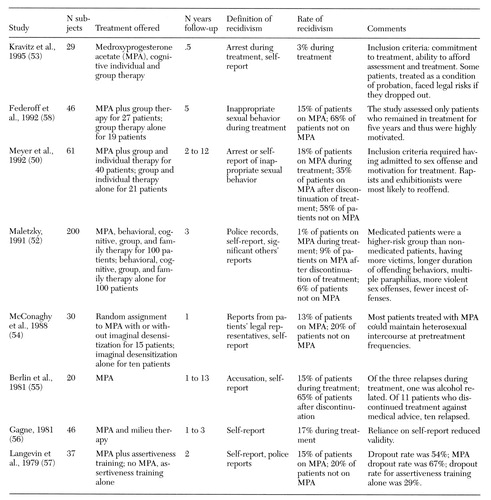

Table 1 summarizes recidivism rates for eight outcome studies of sex offenders treated with antiandrogens (50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58). The studies report a spectrum of differences between patients treated with antiandrogens and those not treated, with recidivism rates as low as 1 percent for treated patients and as high as 68 percent for untreated patients. Recidivism rates for patients initially treated with antiandrogens who discontinued treatment fell between the rates for completers and nontreated patients.

Although the number of studies like these is still small, antiandrogen medication appears promising in the treatment of sex offenders, especially because the effectiveness of antiandrogens in reducing sexual behavior generally is well documented. The outcome studies suggest that antiandrogens, while not effective for all patients (59), appear to reduce sex offender recidivism in many cases.

Research findings have suggested that sex offenders treated with MPA may experience suppression of deviant fantasies and behaviors earlier in treatment (one to two weeks) than suppression of nondeviant fantasies and behaviors (two to ten) (53). If these results are confirmed, they suggest that careful dose titration may allow patients to maintain appropriate sexual behavior while eliminating deviant behavior. Low-dose oral administration of MPA has been attempted, but rigorous research is needed (60).

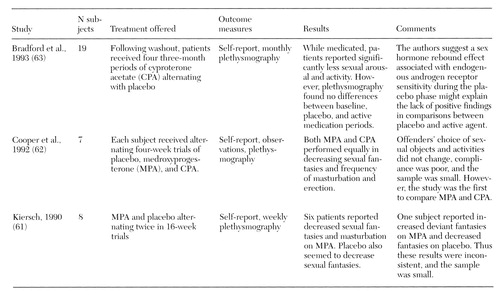

Although placebo-controlled studies may be difficult to achieve with antiandrogens, some have been attempted. Table 2 summarizes the results of three placebo-controlled double-blind crossover studies (61,62,63), which show mixed results. All three studies alternated antiandrogens with placebo, using each subject as his own control. These studies all showed that during the active phase of medication, patients reported decreases in some aspects of their sexual behavior, including deviant sexual thoughts, fantasies, and frequency of masturbation. However, in all three studies, plethysmography did not consistently support patients' self-report. Indeed some patients showed increased deviant arousal while on antiandrogens and decreased deviant arousal during the placebo phase. Bradford and Pawlak (63) suggested that an endogenous sex hormone rebound effect associated with androgen receptor sensitivity during the placebo phase might explain the lack of positive findings in some comparisons between placebo and active agent.

Previously, direct comparisons of MPA and CPA were not done because the two drugs were not available in the same country. In 1992 Cooper and associates (62) provided the first direct comparison of the two agents. The results suggested that MPA and CPA performed equally in decreasing sexual thoughts and fantasies, frequency of masturbation, and erection.

Thus outcome studies of antiandrogen treatment appear promising. However, certain cautions apply:

• The drugs must be used cautiously in treating patients with migraine, asthma, or cardiac dysfunction and are contraindicated for patients with diseases affecting testosterone production (53).

• They may produce side effects, including weight gain, depression, hyperglycemia, hot and cold flashes, headaches, muscle cramps, phlebitis, hypertension, gastrointestinal complaints, gallstones, penile and testicular pain, and diabetes mellitus (50,53). CPA can cause feminization (45).

• As with many other forms of treatment, antiandrogen medication is associated with high dropout rates (50,57,58).

• Antiandrogen treatment requires a level of medical management that can be costly, reducing its availability to broad populations.

• The long-term consequences of use of these drugs are not known; some clinicians recommend using them for only short time periods (52).

Newer hormonal therapiesand serotonergic agents

Several case reports have suggested that analogues of gonadotropin-releasing hormone may be useful either alone or in combination with antiandrogens (64,65,66). These agents inhibit the secretion of luteinizing hormone with a resulting decrease in plasma testosterone levels and libido (45). Dickey (59) described the use of a long-acting depot-injectable luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist in treatment of a patient with multiple paraphilias who had shown a poor response to both MPA and CPA. The patient was reported to have complete cessation of deviant sexual behavior after one month of treatment and decreased frequency of masturbation. The use of LHRH agonists apparently avoids unwanted side effects seen with MPA and CPA (59).

In a recent open study, Rosler and Witztum (65) treated 30 men with severe longstanding paraphilias with monthly injections of triptorelin, a long-acting agonist analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, for eight to 42 months. The results indicated that all men showed a decrease in deviant sexual fantasies, desires, and abnormal sexual behavior. These effects persisted in all of the 24 men who continued in treatment for one year. Treatment was associated with suppression of serum testosterone. Further study is needed before conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy and safety of these agents. However, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and related agents may provide alternative hormonal therapy in cases where antiandrogens fail (59).

A number of small studies and case reports (67,68,69,70,71,72) have found treatment with antidepressants helpful for patients with paraphilias. These studies have included patients for whom tricyclics or lithium was used (70). However, most of the more recently reported successes have been with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (67,68,69). Many patients in these series were reported to have concurrent mood or anxiety disorders. The anxiolytic buspirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, has also been reported effective in reducing paraphilic fantasies (67,68,73,74).

These reports have noted that the serotonergic agents, including buspirone, appear to have specifically antiobsessional effects in patients with paraphilias and related sexual obsessions; such clinical observations are consistent with the demonstrated efficacy of SSRIs for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although these findings are mostly anecdotal, further research could confirm a role for SSRIs, other antidepressants, or other serotonergic agents in the treatment of paraphilias. Clearly, in the presence of comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders, a trial of these agents may be indicated.

Psychological andbehavioral treatment

Psychological treatment of sex offenders showed little success until the advent of cognitive-behavioral techniques (7), which have undergone rapid development over the past two decades. The goal of these treatments is to change sex offenders' belief systems, eliminate inappropriate behavior, and increase appropriate behavior by modifying reinforcement contingencies so that offensive behavior is no longer reinforced. Techniques aimed at eliminating deviant arousal include aversion treatment, covert sensitization, imaginal desensitization, and masturbatory reconditioning. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for sex offenders often includes cognitive restructuring, that is, modification of distorted cognitions used to justify paraphilic behavior (75), social skills training, victim empathy training, lifestyle management, sex education (76), and relapse prevention (77).

Cognitive-behavioral techniques

Aversion therapy and covert sensitization

Both aversion therapy and covert sensitization pair deviant sexual fantasies with punishments. In aversion therapy, deviant fantasies are paired with physical punishment (37,76). Patients work with therapists to develop a series of fantasies about the patients' preferred deviant acts. These fantasies are presented verbally to the patient accompanied by an aversive experience such as a harmless but painful self-administered electrical shock or a noxious odor. Alternately, the therapist presents visual depictions involving the deviant fantasy—for example, depictions of young children—and the patient receives a shock or odor when viewing them. Appropriate visual stimuli such as depictions of adults are also presented, without an accompanying shock or odor.

Covert sensitization pairs deviant sexual fantasies with mental images of distressing consequences. In this technique, offenders verbalize a detailed deviant fantasy. When they become aroused, they discontinue the deviant fantasy and begin verbalizing an equally detailed fantasy of highly aversive consequences, such as being arrested. This technique requires them to focus attention on negative consequences that they find upsetting.

During treatment, offenders identify and focus on the chain of events leading up to the sex offense. This process enables them to insert fantasies of aversive consequences at progressively earlier phases of the predatory behavior leading to a sexual offense. The procedure is thought to teach offenders that their behavior is under their own control and can be interrupted by them at any stage.

Sometimes sex offenders are required to subject themselves to a noxious odor to augment the negative impact of the fantasized aversive consequences. When they become anxious from this fantasy, they are required to begin to fantasize that they "escape" the aversive scene by imagining a nondeviant sexual scene, such as consensual adult sex.

Imaginal desensitization

Imaginal desensitization is a technique in which offenders are trained in deep muscle relaxation (54). When they have learned the relaxation technique, they fantasize the first scene from the chain of events they have previously identified as leading to an act of sexual offense. After they can visualize the first scene and remain relaxed, they are asked to imagine the next scene, and to proceed through the chain, while remaining relaxed. This technique is thought to teach offenders that they can tolerate the feelings associated with their deviant sexual urges, without acting on them, until the urges recede.

Masturbatory reconditioning

Masturbatory reconditioning involves the use of the naturally reinforcing properties of orgasm to change behavior. Various techniques have been proposed to change masturbatory fantasies by requiring the sex offender to change from deviant to nondeviant fantasies at the point of ejaculation (79). Another type of masturbatory reconditioning, satiation, attempts to eliminate deviant sexual arousal by removing its reinforcing properties or supplanting them with aversive properties. Two forms are generally used—verbal satiation and masturbatory satiation (80,81).

In verbal satiation, offenders verbalize deviant sexual fantasies for a prolonged period, until these fantasies become tedious. In masturbatory satiation, offenders masturbate to orgasm while verbalizing nondeviant fantasies, and they then continue masturbating during the refractory period for a prolonged time while verbalizing deviant fantasies. This technique pairs the pleasure of orgasm with appropriate fantasy material, and the pain or boredom of prolonged masturbation without ejaculation with deviant fantasies.

Satiation has received support from several studies (11,79,80,81), but further controlled studies are needed to validate the technique. Approximately 20 hours of masturbatory satiation are estimated to be generally required for treatment efficacy (82).

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring is based on the theory that sex offenders develop numerous distorted beliefs to justify their deviant sexual behavior. These distortions help such individuals to relieve feelings of guilt or shame associated with their offenses (14,75,83). For example, child molesters may assert that children enjoy sex with adults or that sex with adults is good for children.

Cognitive restructuring involves confronting and changing such distorted beliefs. It requires the sex offender to define his cognitions and then discuss the ways he uses these distorted beliefs to rationalize deviant behavior. The therapist challenges his beliefs and suggests new formulations. Role playing in which the therapist plays the role of the offender and the offender plays the role of the police or of an abused family member is often included (13). In this way, the offender must dispute his own beliefs.

Social skills training

Social skills training has been attempted on the theory that deficits in skills necessary for successful interaction in social and nondeviant sexual situations may be involved in sexually deviant behavior. This theory has been debated in the literature (84,85). Social skills training focuses on skills involved in social conversations using role playing, modeling by the therapist, and identification of irrational fears deriving from social conversations. Some programs focus on social anxiety, conflict resolution, and anger management (86). Assertiveness training has also been used to help patients express themselves more effectively (13). Some clinicians believe sex education in conjunction with social skills training is helpful (13).

Victim awareness or empathy

Many offenders minimize the consequences of their deviant sexual behaviors by developing cognitive distortions that allow them to believe their victims were not injured by them or enjoyed the event. Victim awareness or empathy techniques attempt to increase sex offenders' understanding of the impact of their deviant sexual behaviors on their victims. This may involve offenders' viewing videotapes of victims' descriptions of their own experiences, role playing, and receiving feedback from therapists, other offenders, or victims (77).

Relapse prevention

A central feature of many therapies is relapse prevention involving maintenance strategies to anticipate and resist deviant urges (77,87). Relapse prevention is based on the view that relapse occurs in predictable sequences that offenders can avoid if they can identify and interrupt them. The essential components of relapse prevention involve the offender's identification of high-risk situations and the decisions he makes that lead him closer to relapse. He must learn skills to cope with the high-risk situations so as to prevent relapse.

Outcome studies ofcognitive-behavioral treatment

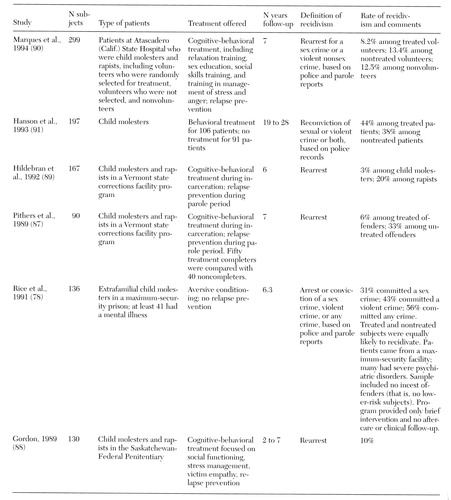

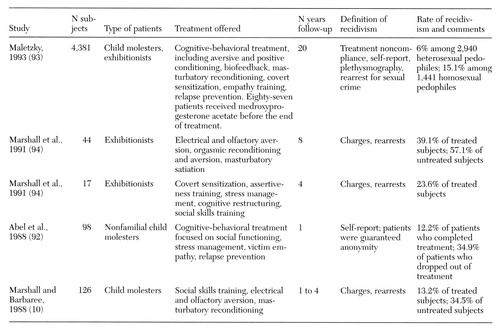

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the methods and results of institutional and outpatient treatment programs, respectively.

As Table 3 shows, recidivism rates from cognitive and behavioral treatment programs that have been offered in institutional settings range from 3 to 31 percent for sex crimes, depending on the study (78,87,88,89,90,91). Of the studies that compared treated to untreated subjects, two programs presented lower recidivism rates for treated subjects (87,89,90), and two programs showed no differences (78,91).

It is possible that the lack of treatment efficacy in the studies by Rice and associates (78) and Hanson and colleagues (91) reflects the fact that neither of these programs offered modern innovations such as cognitive techniques or relapse prevention. In addition, the lack of treatment efficacy in the Rice study may be a function of the characteristics of the sample, which included patients with very poor prognoses. In the Hanson study, lack of efficacy may be a function of this study's extremely long follow-up period.

Table 4 summarizes studies of outpatient psychological and behavioral treatment programs. These studies provide promising data for treatment efficacy. Recidivism rates ranged from 6 to 39 percent for treated subjects (10,92,93,94), with one sample of nearly 3,000 heterosexual pedophiles showing a recidivism rate of only 6 percent over a very long period of time (93). Treated subjects all showed lower recidivism rates than did their untreated counterparts.

Overview of treatment efficacy

Several investigators have compiled the data from treatment outcome studies, despite variation in types of treatment, patients treated, and research design. Furby and colleagues (95) amassed data from numerous studies of sex offenders that included at least ten subjects and used criminal justice records for outcome measures. The review covered almost 7,000 men. The authors concluded that their review failed to provide any convincing evidence that treatment is effective in reducing recidivism of sexual offenses. They further stated that their data did not permit evaluation of the relative effectiveness of treatment for different types of offenders. In fact, the authors reported difficulty discerning any patterns relating treatment to recidivism, including the expected pattern that longer follow-up periods would produce higher recidivism rates.

When these authors compared treated patients to untreated patients, they found that untreated patients had recidivism rates below 12 percent, while treated sex offenders in two-thirds of the studies had recidivism rates above 12 percent. The authors suggested that treatment outcome studies may monitor subjects more closely during the follow-up period, leading to a greater likelihood of detection of subsequent arrests. Further, they suggested that pre-existing differences between treated and untreated sex offenders—apart from whether they received treatment—may mean that any conclusions to be drawn must remain tentative (95).

Marshall and Pithers (6) criticized the Furby review, arguing that its findings are no longer applicable since they are based on studies mostly published before 1978, before the use of the cognitive-behavioral techniques so prevalent today. Indeed most of the programs reviewed by Furby and colleagues no longer exist. Further, Marshall and Pithers argued that the samples reviewed by Furby and colleagues overlap in at least one-third of the studies reviewed, which biases the results against positive findings. Thus Marshall and Pithers concluded that the findings of the Furby review are inappropriately pessimistic.

The best methodology for integrating the sex offender treatment data is meta-analysis. Until recently, this procedure was precluded by the inadequate descriptions in many studies of sampling techniques or outcome measures, differences in sample sizes, types of subjects assessed, types of treatment, and length of follow-up. However, a meta-analysis by Hall (96)—although limited to only 12 studies—provided an overall estimate of the results of treatment for sex offenders. This analysis included all published studies since the Furby review that compared samples of more than ten offenders who had completed a treatment program with others who had completed a comparison program or no treatment program, and that used arrest records for sexual offenses as outcome data. The mean length of treatment in the studies was 18.5 months, and the mean follow-up period was 6.9 years. Overall, the analysis found that the recidivism rate for treated offenders was 19 percent, compared with 27 percent for nontreated offenders.

The meta-analysis found that cognitive-behavioral treatment and antiandrogen treatment were comparable in their treatment effects and significantly more effective than behavioral treatment alone (96). It is noteworthy that effect sizes—indexes of the strength of treatment outcome—were significantly greater in studies of outpatients than in studies of institutionalized patients and were greater in studies with follow-up periods of longer than five years. Effect sizes did not differ between studies that included rapists and those that did not.

Larger effect sizes were also found for patients with higher base rates of recidivism, which according to the author could reflect greater difficulty demonstrating statistically significant treatment effects in groups with low base rates of recidivism. Although the use of arrest records as recidivism criteria may underestimate recidivism, differences related to treatment should not be invalidated by this limitation because any underestimation should apply equally to treated and untreated groups.

When considering whether a sex offender is a candidate for antiandrogen treatment or cognitive-behavioral therapy, Hall (96) pointed out that although the two forms of treatment are equally successful, the dropout rates for hormonal therapy are greater. Two-thirds of participants refused hormonal treatment (50,58), and 50 percent of patients who began this type of treatment discontinued it before completing the program (57). In contrast, dropout and refusal rates for cognitive-behavioral treatment were about one-third (92). In addition, hormonal treatments impose potential adverse medication effects and possible longer-term health risks. Obviously, cognitive-behavioral treatment avoids these problems. On the other hand, for patients who can tolerate hormonal treatment, this form of intervention may prove particularly effective. The cost-effectiveness of different treatments deserves further study.

In a large recidivism study of 408 sex offenders followed up over a mean of four years and in some cases up to ten years, Bench and colleagues (9) used discriminant analysis to identify factors predictive of recidivism. Of most interest, the total number of felony convictions was the strongest predictor of recidivism involving sex-related offenses. Failure to complete treatment was a weaker but significant predictor as well. When a broader definition of recidivism that included nonsex offenses and probation or parole violations was used, failure to complete treatment emerged as the strongest predictor of recidivism.

A recent meta-analysis of factors predicting recidivism based on 61 follow-up studies of 23,393 sex offenders found that failure to complete treatment was associated with higher risk of recidivism of sex offenses (97). Perhaps surprisingly, variables not associated with higher risk of recidivism of sex offenses included denial of responsibility, low motivation for treatment, length of treatment, and empathy with victims. The strongest predictor of sexual reoffense in this meta-analysis was sexual interest in children as measured by plethysmography. When the definition of recidivism was broadened to include any crime, increased risk was associated with premature termination of treatment, denial, and low motivation for treatment. Taken together, these meta-analyses suggest that failure to complete treatment is a significant predictor of criminal recidivism, including sexual reoffense, in this population.

Conclusions

Although some forms of treatment for sex offenders appear promising, little is known definitively about which treatments are most effective, or for which offenders, over what time span, or in what combinations. What emerges from the literature is a strong suggestion that a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral program should involve components that reduce deviant arousal while increasing appropriate arousal and should include cognitive restructuring, social skills training, victim empathy awareness, and relapse prevention. In addition, patients should be considered for antiandrogen medication if they are at high risk of reoffending.

In general, results from biological and cognitive-behavioral treatment programs strongly suggest that treatment decreases recidivism of sexual crimes. In evaluating whether the amelioration produced by treatment is clinically significant, Hall's meta-analysis (96) suggested that antiandrogen and cognitive-behavioral treatment lead to a decrease in recidivism from a baseline rate of 27 percent in untreated individuals to a rate of 19 percent in patients who receive treatment. Hall summarized these findings as an outcome of eight fewer sex offenders per 100.

However, the results of his meta-analysis may be viewed in another way: from a baseline recidivism rate of 27 percent, a decrease in recidivism among treated patients to a level of 19 percent amounts to a 30 percent remission rate as a result of treatment. When viewed from this perspective, the analysis suggests an outcome of 30 fewer sex offenders per 100, and it reflects a follow-up period of nearly seven years. This outcome is not a negligible impact from the standpoint of clinical treatment.

By comparison, lithium prophylaxis of bipolar disorder—a standard treatment for a well-established psychiatric illness—was found in a recent five-year prospective study to be associated with complete remission in approximately 38 percent of patients still taking lithium (98). Because a number of other patients dropped out of this study due to perceived lack of efficacy of lithium, this percentage may actually overestimate lithium's medical effectiveness.

Zonana (3) has suggested, however, that the consequences of recidivism in sex offenders are so detrimental to society that a recidivism rate of zero is the only acceptable risk level. Such an assumption could lead to the conclusion that indefinite confinement is the only conceivable effective intervention with or without medical treatment. But the demonstrated reduction in recidivism that emerged in the meta-analysis of research on treatment of sex offenders is a robust finding and suggests that treatment for patients in this population improves outcome and may protect potential sexual assault victims.

Recent legislation in an increasing number of states focusing on the preventive detention of sexually violent persons has stimulated vigorous legal and policy discussion and debate (1,2, 3). This newer legislation may have significant impact on public mental health systems because the proceedings involve civil commitment rather than criminal prosecution and are associated with mandates for medical evaluation and treatment. Clinicians have not traditionally regarded sex offenders as falling within the target population of severely and persistently mentally ill persons considered appropriate for civil commitment.

Yet although it may be true that, in general, public mental health programs have little to offer by way of a service line tailored to this population, it is far less clear that individuals exhibiting chronic, repeated sexually aggressive behaviors do not suffer from mental illnesses. Nor is it clear that psychiatric treatment is without benefit for this patient population, despite frequent anecdotal references to the lack of effective treatments. To the contrary, research provides evidence of a robust treatment effect that has the potential to reduce sexually aggressive behavior.

Although the conclusion that sex offenders are untreatable is unwarranted, caution must be exercised in unfolding the implications of the positive treatment findings in the literature. It is worth underscoring the finding of Hall's meta-analysis (96) that treatment of outpatients was associated with a larger treatment effect than treatment of institutionalized individuals. Further, in the discriminant analysis of Bench and colleagues (9), failure to complete treatment was a weak predictor of sex-offense-specific recidivism in comparison with the extent of the felony conviction record.

These findings appear to suggest, unfortunately, that the more a sex offender needs confinement, the less confident we can be that treatment will have lasting benefits. Paradoxically, however, it is precisely the more dangerous subset of patients that psychiatry is being called to treat based on the new legislation. Civil commitment of sex offenders is based on the problem of perceived persistent dangerousness.

Precautions must be taken to ensure that treatment environments are appropriate for the risk level presented by these patients. Psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and public administrators are concerned about the potential for predatory behavior by sex offenders who are mixed with the currently defined population of patients with serious and persistent mental illness. Criteria must be developed to determine which sex offenders are more appropriate for outpatient programs and to provide a rational basis for transitioning patients from institutional to outpatient care. Civil commitment to outpatient treatment may provide a more appropriate level of care for many patients than psychiatric hospitalization in traditional general inpatient settings.

Finally, from a scientific standpoint, there remain significant problems with the available data from sex offender treatment studies. An optimistic perspective must be entertained cautiously and accompanied by a commitment to the advancement of scientific knowledge in the field. This perspective is not new to psychiatry, where gains in knowledge about treatment of chronic illnesses such as schizophrenia have been gradual and hard earned. Yet as Bradford (66) recently pointed out, support for the scientific study of deviant sexual behavior has not kept pace with the apparent—or at least official—public sentiment about the management of sexual aggressors. It would be informative for such research to include a focus on sex offenders from additional populations, such as women and adolescents.

Treatments for sex offenders do exist, and the outcome data are not uniformly discouraging. They are, however, complex, difficult to interpret, and cause for cautious optimism at best. If mental health professionals and society at large are to accept the challenge of promoting treatment for sex offenders, vigorous ongoing research efforts are mandatory.

Dr. Grossman is director of training in psychology and professor of psychology and Dr. Martis is a psychiatric resident in the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago, 912 South Wood Street (M/C 913), Chicago, Illinois 60612 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Fichtner is medical coordinator for mental health services with the Illinois Department of Human Services and associate professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Finch University of Health Sciences/Chicago Medical School.

|

Table 1. Results from outcome studies of sex offenders treated with antiandrogens

|

Table 2. Placebo-controlled double-blind crossover studies of sex offenders treated with antiandrogens

|

Table 3. Studies of psychological and behavioral treatment programs for sex offenders offered within institutions

|

Table 4. Studies of psychological and behavioral treatment programs for sex offenders offered in outpatient settings

1. Cohen F: Sexually dangerous persons/ predators legislation, in The Sex Offender: New Insights, Treatment Innovations, and Legal Developments, vol 2. Edited by Schwartz B, Cellini H. Kingston, NJ, Civic Research Institute, 1997Google Scholar

2. Covington JR: Preventive detention for sex offenders. Illinois Bar Journal 85:493-498, 1997Google Scholar

3. Zonana H: The civil commitment of sex offenders. Science 278:1248-1249, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Grossman LS: Research directions in the evaluation and treatment of sex offenders: an analysis. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 3:421-440, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Marshall WL, Jones R, Ward T, et al: Treatment outcome with sex offenders. Clinical Psychology Review 11:465-485, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Marshall WL, Pithers WD: A reconsideration of treatment outcome with sex offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior 21:10-27, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Abel GG, Osborn C, Anthony D, et al: Current treatments of paraphiliacs. Annual Review of Sex Research 3:255-290, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Abel GG, Becker JV, Mittelman M, et al: Self-reported sex crimes of nonincarcerated paraphiliacs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 2:3-25, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Bench LL, Kramer SP, Erickson S: A discriminant analysis of predictive factors in sex offender recidivism, in The Sex Offender: New Insights, Treatment Innovations, and Legal Developments, vol 2. Edited by Schwartz B, Cellini H. Kingston, NJ, Civic Research Institute, 1997Google Scholar

10. Marshall WL, Barbaree HE: The long-term evaluation of a behavioral treatment program for child molesters. Behaviour Research and Therapy 26:499-511, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Marshall WL, Barbaree HE: An outpatient treatment program for child molesters. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 528:205-214, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Groth AN, Longo RE, McFadin JB: Undetected recidivism among rapists and child molesters. Crime and Delinquency 28:450-458, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Abel GG, Becker JV, Cunningham-Rathner J, et al: The Treatment of Child Molesters. Atlanta, Behavioral Medicine Institute of Atlanta, 1984Google Scholar

14. Abel GG, Becker JV, Cunningham RJ: Complications, consent, and cognitions in sex between children and adults. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 7:89- 103, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Abel GG, Barlow DH, Blanchard EB, et al: The components of rapists' sexual arousal. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:895-903, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Abel GG, Blanchard EB, Barlow DH, et al: Identifying specific erotic cues in sexual deviations by audiotaped descriptions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 8:247-260, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Abel GG, Blanchard EB, Becker JV, et al: Differentiating sexual aggressiveness with penile measures. Criminal Justice and Behavior 5:315-332, 1978Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Barbaree HE, Marshall WL: The role of male sexual arousal in rape: six models. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59:621-630, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Barbaree HE, Serin RC: Role of male sexual arousal during rape in various rapist subtypes, in Sexual Aggression: Issues in Etiology, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Hall GCN, Hirschman R, Graham JR, et al. Kent, Ohio, Taylor & Francis, 1993Google Scholar

20. Quinsey VL, Chaplin TC: Stimulus control of rapists' and non-sex offenders' sexual arousal. Behavioral Assessment 6:169-176, 1984Google Scholar

21. Quinsey VL, Chaplin TC: Penile responses to nonsexual violence among rapists. Criminal Justice and Behavior 9:372-381, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Avery CCA, Laws DR: Differential erection response patterns of sexual child abusers to stimuli describing activities with children. Behavior Therapy 15:71-83, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Abel GG, Becker JV, Murphy WD, et al: Identifying dangerous child molesters, in Violent Behavior. Edited by Stuart R. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1981Google Scholar

24. Murphy WD, Haynes MR, Stalgaitis SJ, et al: Differentiatial sexual responding among four groups of sexual offenders against children. Journal of Psychopathological Behavior Assessment 8:339-353, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Quinsey VL, Chaplin TC: Penile responses of child molesters and normals to descriptions of encounters with children involving sex and violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 3:259-274, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Farrall WR, Card RD: Advancements in physiological evaluation of assessment and treatment in the sexual aggressor, in Sexual Aggression: Current Perspectives. Edited by Prentky R, Quinsey VL. New York, New York Academy of Sciences, 1988Google Scholar

27. Barbaree HE, Marshall WL: Deviant sexual arousal, offense history, and demographic variables as predictors of reoffense among child molesters. Behavioral Science and the Law 6:267-280, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Marques JK, Day DM, Nelson C, et al: The sex offender treatment and evaluation project. Fourth report to the legislature in response to PC 1365. Sacramento, California Department of Mental Health, 1991Google Scholar

29. Quinsey VL, Chaplin TC, Carrigan WF: Biofeedback and signaled punishment in the modification of inappropriate sexual age preferences. Behavior Therapy 11:567-576, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Maletzky BM: Self-referred versus court-referred sexually deviant patients: success with assisted covert sensitization. Behavior Therapy 11:306-314, 1980Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Blader JC, Marshall WL: Is assessment of sexual arousal in rapists worthwhile? A critique of current methods and the development of a response compatability approach. Clinical Psychology Review 9:569-587, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Grossman LS, Cavanaugh JL, Haywood TW: Deviant sexual responsiveness on penile plethysmography using visual stimuli: alleged child molesters vs normal control subjects. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 180:207-208, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Templeman TL, Stennett RD: Patterns of sexual arousal and history in a "normal" sample of young men. Archives of Sexual Behavior 10:137-150, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Laws DR, Holmen ML: Sexual response faking by pedophiles. Criminal Justice and Behavior 5:343-356, 1978Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Pithers WD, Laws DR: The penile plethysmograph: uses and abuses in assessment and treatment of sexual aggressors, in Sex Offenders: Issues in Treatment. Washington, DC, National Institute of Corrections, 1988Google Scholar

36. Murphy WD, Barbaree HE: Assessments of Sexual Offenders by Erectile Response: Psychometric Properties and Decision Making. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, 1988Google Scholar

37. Rice ME, Harris GT, Quinsey VL: A follow-up of rapists assessed in a maximum-security psychiatric facility. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 5:435-448, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Prentky RA, Knight RA, Rosenberg R, et al: A path analytic approach to the validation of a taxonomic system for classifying child molesters. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 6:231-257, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Hanson RK, Cox BJ, Woszczyna C: Assessing treatment outcome for sexual offenders. Annals of Sex Research 4:177-208, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Cornu F: Catamnestic Studies on Castrated Sex Delinquents From a Forensic Psychiatric Viewpoint. Basel, Germany, Karger, 1973Google Scholar

41. Freund K: Therapeutic sex drive reduction. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 62(suppl):1-39, 1980Google Scholar

42. Texas Government Code, Chpt 501, Subchapt B, Sec 061, 062 (1997)Google Scholar

43. Field LH, Williams M: The hormonal treatment of sexual offenders. Medical Science and Law 10:27, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Foote RM: Diethylstilbestrol in the management of psychopathological states in males. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 99:928-935, 1944Crossref, Google Scholar

45. Bradford JM: Research on sex offenders: recent trends. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 6:715-731, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Field LH: Benperidol in the treatment of sex offenders. Medical Science and the Law 13:195, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Bancroft J, Tennant G, Loucas K, et al: The control of deviant behaviour by drugs. British Journal of Psychiatry 125:310-315, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Zbytovsky J, Zapletalek M: Haloperidol decanoate in the treatment of sexual deviations. Activitas Nervosa Superior 31:41-42, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

49. Bradford JM: The Antiandrogen and Hormonal Treatment of Sex Offenders. New York, Plenum, 1990Google Scholar

50. Meyer WJ, Cole C, Emory LE: Depo Provera treatment for sex offending behavior: an evaluation of outcome. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 20:249-259, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

51. Donovan BT: Hormones and Human Behavior. London, Cambridge University Press, 1984Google Scholar

52. Maletzky BM: Treating the Sexual Offender. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1991Google Scholar

53. Kravitz HM, Haywood TW, Kelly JR, et al: Medroxyprogesterone treatment for paraphiliacs. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 23:19-33, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

54. McConaghy N, Blaszczynski A, Kidson W: Treatment of sex offenders with imaginal desensitization and/or medroxyprogesterone. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 77:199-206, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

55. Berlin FS, Meinecke CF: Treatment of sex offenders with antiandrogenic medication: conceptualization, review of treatment modalities, and preliminary findings. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:601-607, 1981Link, Google Scholar

56. Gagne P: Treatment of sex offenders with medroxyprogesterone acetate. American Journal of Psychiatry 138:644-646, 1981Link, Google Scholar

57. Langevin R, Paitich D, Hucker SJ, et al: The effect of assertiveness training, Provera, and sex of therapist in the treatment of genital exhibitionism. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 10:275-282, 1979Crossref, Google Scholar

58. Federoff JP, Wisner CR, Dean S, et al: Medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of paraphilic sexual disorders: rate of relapse in paraphilic men treated in long-term group psychotherapy with or without medroxyprogesterone acetate. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 18:109-123, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

59. Dickey R: The management of a case of treatment-resistant paraphilia with a long-acting LHRH agonist. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 37:567-569, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

60. Gottesman HG, Schubert DS: Low-dose oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the management of the paraphilias. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:182-188, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

61. Kiersch TA: Treatment of sex offenders with Depo-Provera. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 18:179-187, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

62. Cooper AJ, Sandhu S, Losztyn S, et al: A double-blind placebo controlled trial of medroxyprogesterone acetate and cyproterone acetate with seven pedophiles. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 37:687- 693, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Bradford JMW, Pawlak A: Double-blind placebo crossover study of cyproterone acetate in the treatment of the paraphilias. Archives of Sexual Behavior 22:383-402, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

64. Rousseau L, Dupont A, Labrie F, et al: Sexuality changes in prostate cancer patients receiving antihormonal therapy combining the antiandrogen flutamide with medical (LHRH agonist) or surgical castration. Archives of Sexual Behavior 17:87-98, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Rosler A, Witztum E: Treatment of men with paraphilia with a long-acting analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. New England Journal of Medicine 338:416-465, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

66. Bradford JM: Treatment of men with paraphilia. New England Journal of Medicine 338:464-465, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

67. Kafka MP: Sertraline pharmacotherapy for paraphilias and paraphilia related disorders: an open trial. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 6:109-125, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

68. Kafka MP, Prentky R: Fluoxetine treatment of nonparaphilic sexual addictions and paraphilias in men. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 53:351-358, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

69. Stein DJ, Hollander E, Anthony DT, et al: Serotonergic medications for sexual obsessions, sexual addictions, and paraphilias. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 53:267-271, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

70. Kruesi MJ, Fine MB, Valladares L, et al: Paraphilias: a double-blind crossover comparison of clomipramine versus desipramine. Archives of Sexual Behavior 21:587-593, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

71. Zohar J, Kaplan Z, Benjamin J: Compulsive exhibitionism successfully treated with fluvoxamine: a controlled case study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:86-88, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

72. Bianchi MD: Fluoxetine treatment of exhibitionism. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1089-1090, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

73. Fedoroff JP, Fedoroff IC: Buspirone and paraphilic sexual behavior. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 18:89-108, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

74. Federoff JP: Buspirone in the treatment of transvestic fetishism. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 49:408-409, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

75. Abel GG, Gore DK, Holland CL, et al: The measurement of the cognitive distortions of child molesters. Annals of Sex Research 2:135-152, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

76. Marshall WL, McKnight RD: An integrated treatment program for sexual offenders. Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal 20:133-138, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

77. Laws DR: Relapse Prevention With Sex Offenders. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

78. Rice ME, Quinsey VL, Harris GT: Sexual recidivism among child molesters released from a maximum security psychiatric institution. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59:381-386, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

79. Laws DR, Marshall WL: Masturbatory reconditioning with sexual deviates: an evaluative review. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy 13:13-25, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

80. Laws DR: Verbal satiation: notes on procedure, with speculations on its mechanism of effect. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment 7:155-166, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

81. Gray SR: A comparison of verbal satiation and minimal arousal conditioning to reduce deviant arousal in the laboratory. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment 7:143-153, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

82. Abel GG, Blanchard EB: The role of fantasy in the treatment of sexual deviation. Archives of General Psychiatry 30:467-475, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

83. Ward T, Hudson SM, Marshall WL: Cognitive distortions and affective deficits in sex offenders: a cognitive deconstructionist interpretation. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research and Treatment 7:67-83, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

84. Stermac LE, Segal ZV, Gillis R: Social and cultural factors in sexual assault, in Handbook of Sexual Assault: Issues, Theories, and Treatment of the Offender. Edited by Marshall WL, Laws DR, Barbaree HE. New York, Plenum, 1990Google Scholar

85. Segal ZV, Marshall WL: Heterosexual social skills in a population of rapists and child molesters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 53:55-63, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

86. Cullen M, Freeman-Longo RE: Men and Anger: A Relapse Prevention Guide to Understanding and Managing Your Anger. Brandon, Vt, Safer Society Press, 1995Google Scholar

87. Pithers WD, Cumming GF: Can relapse be prevented? Initial outcome data from the Vermont treatment program for sexual aggressors, in Relapse Prevention With Sex Offenders. Edited by Laws DR. New York, Guilford, 1989Google Scholar

88. Gordon A: Research on sex offenders: Regional Psychiatric Centre. Forum on Corrections Research 1:20-21, 1989Google Scholar

89. Hildebran DD, Pithers WD: Relapse prevention: application and outcome. Sexual Abuse of Children: Clinical Issues 2:365-393, 1992Google Scholar

90. Marques JK, Day DM, Nelson C, et al: Effects of cognitive-behavioral treatment on sex offender recidivism: preliminary results of a longitudinal study. Criminal Justice and Behavior 21:28-54, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

91. Hanson RK, Steffy RA, Gauthier R: Long-term recidivism of child molesters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:646-652, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

92. Abel GG, Mittelman M, Becker JV, et al: Predicting child molesters' response to treatment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 528:223-234, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

93. Maletzky BM: Factors associated with success and failure in the behavioral and cognitive treatment of sexual offenders. Annals of Sex Research 6:241-258, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

94. Marshall WL, Eccles A, Barbaree HE: The treatment of exhibitionists: a focus on sexual deviance versus cognitive and relationship features. Behaviour Research and Therapy 29:129-135, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

95. Furby L, Weinrott MR, Blackshaw L: Sex offender recidivism: a review. Psychological Bulletin 105:3-30, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

96. Hall GCN: Sexual offender recidivism revisited: a meta-analysis of recent treatment studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 63:802-809, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

97. Hanson RK, Bussiere MT: Predicting relapse: a meta-analysis of sexual offender recidivism studies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:348-362, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

98. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, et al: Long-term outcome of lithium prophylaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients at a lithium clinic. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:30-35, 1998Link, Google Scholar