Child Psychiatrists as Leaders in Public Mental Health Systems: Two Surveys of State Mental Health Departments

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purposes of the study were to document the administrative roles that child psychiatrists play in the development of policy in state departments of mental health and to identify barriers to their participation. METHODS: A survey was sent to the director of the department of mental health in each U.S. state and territory to determine the administrative duties of child psychiatrists who work in the department's central administration. A follow-up survey was sent to directors of children's services in state departments of mental health to determine what skills child psychiatrists would need to develop to increase their likelihood of being selected for administrative leadership positions. RESULTS: Nine of the 31 departments of mental health that responded to the first survey had formalized central administrative roles for child psychiatrists as either an administrative consultant or a children's medical director. The 19 respondents to the second survey indicated that to play a role in the central administration of state departments of mental health, most child psychiatrists needed improved knowledge in cultural competency, organizational dynamics, how government functions, the use of an asset-based approach to dealing with families, and use of interventions other than inpatient units, outpatient medication, or psychotherapy. CONCLUSIONS: To improve the leadership role of child psychiatrists in public-sector systems, training opportunities should be developed to increase their knowledge and skills in areas needed for effective participation in policy development. Training should include formal didactic instruction and clinical experiences that focus on the wide range of interventions used in public-sector systems and on the administrative skills needed for leadership positions.

The state department of mental health is usually the single largest provider of mental health services for children in any state. Services are provided through direct patient care, through the management of clinical services provided by private administrative agents, or by county mental health authorities and other local government entities.

State departments of mental health usually have close working relationships with key members of the state legislative and executive branches. As a result, the department plays a strong role in shaping policy initiatives that will affect mental health services for children in both the private and the public sector. If child and adolescent psychiatry as a discipline hopes to have a leadership role in shaping mental health policy for children, child psychiatrists need to have a role in the leadership of state departments of mental health.

The literature is especially silent on what roles child and adolescent psychiatrists play in public mental health leadership. Published discussions are more likely to address the role of psychiatrists as a group rather than to try to identify special roles subspecialists may play (1,2,3,4,5). Similarly, the literature that addresses barriers to psychiatrists' taking on administrative leadership roles does not distinguish between general psychiatrists and child and adolescent psychiatrists (6,7).

Rafferty (8) observed that before the 1960s, child and adolescent psychiatrists were largely excluded from the power structure of state mental health agencies due to a paucity of services for children in adult-centered state hospitals. Because few child psychiatrists had positions in central administration before the community mental health movement, they were not considered for managerial positions as the states began building their community systems of care. The main role of child psychiatrists was to provide clinical services. Rafferty further noted that the absence of administrative participation by child psychiatrists resulted in a tendency for budgetary shortfalls to occur in public child and adolescent services through the 1970s and 1980s. Such services tended to be regarded as "add-ons" and were financed reluctantly. Pumariega and associates (9) have asserted that the medicalization of psychiatry during the 1970s and 1980s led child and adolescent services to move to a hospital-based, tertiary care model and that this move in turn led to spiraling costs in both the private and the public sectors.

In the 1990s, with the advent of public-sector managed care and other cost-containment efforts, mental health services have shifted to primarily community-based systems of care (10). The community-based movement further circumscribed the contributions of child psychiatrists to public-sector leadership, because their experience was predominantly in inpatient settings. The lack of familiarity with today's system of care presents a significant barrier to child psychiatrists' ability to exert leadership roles in public systems.

This paper presents the results of two surveys that examined the roles child psychiatrists currently play in formulating public mental health policy, describes barriers to their involvement in this area, and makes recommendations for improving the leadership role of child psychiatrists.

Methods

A preliminary point-in-time survey was developed to obtain information on the role child psychiatrists play in the central administration of departments of mental health. The survey used closed- and open-ended questions to ascertain what administrative roles child and adolescent psychiatrists play in central management of departments of mental health and what barriers might exist to their taking on administrative roles. With the assistance of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, the survey was sent in August 1997 to the director of the department of mental health in each of the 50 U.S. states and five territories.

Based on responses to the preliminary survey about skills or knowledge that child psychiatrists lacked, making them less suited for leadership positions than members of other disciplines, we developed a second survey focused more narrowly on children's services. The second survey was distributed in February 1998 to directors of children's services in state departments of mental health through the children's services division of the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors.

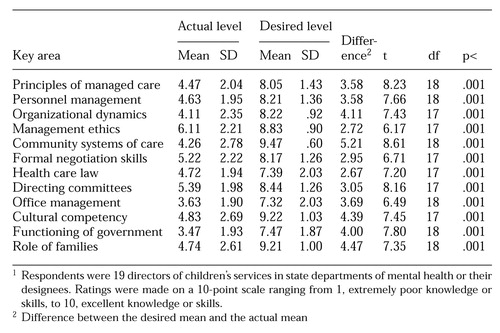

The second survey asked respondents to assess the knowledge level of most child psychiatrists in 12 key areas on a scale of 1 to 10, on which 1 indicated extremely poor knowledge and 10 indicated excellent knowledge of the topic. Brief descriptions of the 12 key areas were provided (see accompanying box). On a second 10-point scale, respondents were asked to indicate the level of knowledge child psychiatrists would need to assist effectively in developing policy and addressing administrative issues in state departments of mental health. Differences between the ratings on the actual knowledge scale and the desired knowledge scale were tested for statistical significance using t tests (two tailed) for correlated samples.

Participants in both surveys were assured that their individual responses would be kept confidential and would be reported only in aggregate.

Survey items describing key skills and areas of knowledge needed by child psychiatrists in leadership positions in public-sector mental health systems

Principles of managed care: Principles of managed care and insurance coverage issues, including rules and regulations of private indemnity insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare; issues to be aware of when negotiating managed care contracts and interacting with managed care companies; basic procedures for forming capitated or bundled rates of services

Personnel of management: Recruiting and hiring effective staff members, motivating staff members to function as good team members and to work together with others, dealing effectively with difficult employees

Organizational dynamics: Understanding how large health care systems work, mobilizing groups of people in an organization to work together to effectively produce needed change

Management ethics: Understanding the ethics of working in the public sector, including ethical principles of dealing with managed care and with employees and other staff as well as upper-level mangers

Community systems of care: Understanding the elements of systems of care beyond inpatient and outpatient psychiatric services, including principles of case management, design of a continuum of care, knowledge of how function in settings besides inpatient and outpatient services, and use of wrap-around services

Formal negotiation skills: Knowledge of techniques for negotiation in management settings anf for creating win-win situations when dealing with difficult people in managerial sessions

Health care law: Familiarity with legal topics beyond malpractice law, including application of the law to health care systems, antitrust law, antidumping statutes, application of the law to medical staff issues, and knowing when to seek legal counsel

Directing committees or subcommittees: Knowing how to lead a committee or task force effectively to evaluate problems in service delivery

Office management: Using practical problem solving related to budget development, dealing with cost overruns on clinical units, and formulating actions that will result in more cost-effective delivery services

Cultural competency: Knowledge of the effects of culture on the presentation of mental illness and of the impact of culture on use of mainstream psychiatric services and the ability to apply that knowledge

Functioning of government: Understanding legislative processes, including how laws are developed and passed and state budgeting and taxation processes, and possessing the ability to work effectively with these processes

Role of families: Ability to view families not as sources of pathology but as powerful resources capable of actively contributing to a child's treatment and to involve families effectively in treatment

Results

The first survey

Respondents from 31 of the 55 states and territories returned surveys. Eleven respondents were located in the Midwest, nine in the East, six in the West, and five in the South. Respondents were directors of state departments of mental health or their designees. Fourteen respondents were psychiatrists, and seven were child psychiatrists. Six respondents were master's-level social workers or family services specialists, five were psychologists, and four had management or administrative backgrounds. The disciplinary background of two respondents was unknown.

Seven surveys were completed by the director of the state department of mental health. The others were delegated for completion by the state medical director (11 surveys), by children's services administrative staff (11 surveys), and by administrators in other roles (two surveys). We found no significant differences between the responses based on professional background or administrative role.

Nine respondents reported that the state had formally created a position for a child psychiatrist who served as an administrative consultant for children's programs. One respondent reported that the state was developing such a position, and two reported that the state was using child psychiatrists in an administrative capacity on a trial basis to determine if establishing such a position would be beneficial.

Of the formally established positions, six had been created in the last six years. The only full-time-equivalent (FTE) position was being converted to a part-time position. The others were .6 FTE or less. The duties of these consultants were quite varied. All performed clinical-administrative consultation to help develop new programs and improve existing ones or improve services to difficult clinical populations. Five helped guide policy recommendations and develop budgets. Other roles included coordinating training efforts, conducting utilization reviews, serving as a liaison to other agencies that serve children, and guiding special projects or task forces. Respondents were asked if the state would keep the position in the face of a 10 percent administrative budget cut. They indicated that five states would keep the position, one would not, and three were undecided.

Twenty-two states had no formalized administrative role for child psychiatrists. Only seven of these states consistently obtained input from clinicians in the field on administrative issues. Many respondents cited barriers that prevent child psychiatrists from having roles in central administration. Nine held that child psychiatrists were hard to recruit to meet clinical needs, much less to act as administrators. Eight indicated that budgetary issues and the expense of child psychiatrists were significant barriers to using them in central administrative capacities. Six thought that child psychiatrists do not understand how government systems work, lack basic administrative skills such as personnel management and financial management, or are unfamiliar with the array of nontraditional services being developed in state systems to provide for a full continuum of care. Only one of these six respondents indicated that the state had a child psychiatrist functioning in an administrative role.

Three respondents indicated that because most of the state's services were provided to adults, children's psychiatric services did not need an administrative child psychiatrist. Other individual responses suggested that a general psychiatrist serving as overall state medical director would have enough knowledge of child psychiatry to provide input when needed, that child psychiatrists wanted to dictate courses of action rather than negotiate, and that psychiatrists were not generally used in central administration. Two respondents indicated that their states had just never thought of having a child psychiatrist on the central staff.

Child psychiatrists did function in roles not specifically designed for the subspeciality. Five child psychiatrists served as medical director or assistant medical director for all psychiatric services, one served as state director of mental health, and one served as director of children's services. Only six respondents reported that a child psychiatrist had ever been the director of children's psychiatric services for their state's department of mental health. In three of these cases, no child psychiatrist had held the position of children's services director in more than a decade.

The second survey

Twenty-one responses were obtained from the 55 surveys that were distributed. Two surveys were dropped from the analysis because they were completed improperly. Of the 19 respondents whose surveys were used in the analysis, six had a background in psychology, five in health care administration, and four in psychiatry. Three were master's-level social workers. The disciplinary background of one respondent was unknown.

Eleven respondents were state children's services directors, five were other staff in the children's services division, and three were child psychiatrists providing services to the administration of the department of mental health. Survey responses from seven states and territories in the East, five in the West, four in the South, and three in the Midwest were used in the analysis. We found no significant differences in the responses based on the respondents' professional field or current administrative role.

As Table 1 shows, policy makers rated the actual knowledge of child psychiatrists in all 12 areas included in the survey as significantly below the desired level of knowledge expected of persons involved in policy development. A post-hoc analysis, with Bonferroni correction, revealed no significant differences in ratings based on respondents' occupation or geographic location. Child psychiatrists were rated lowest in their understanding of systems of care beyond inpatient and outpatient interventions such as medication and psychotherapy. They were considered deficient in their knowledge of principles of case management, in their skill in designing programming for a full continuum of care, and their likelihood of using nontraditional wrap-around services.

Policy makers also rated child psychiatrists as having a poor understanding of the role of families in public mental health. Respondents indicated that public systems prefer to view families as powerful resources whose strengths should be enhanced, while child psychiatrists tend to view families as sources of pathology. Other major deficiencies were perceived in knowledge of cultural competency, organizational dynamics, and the functioning of government.

Respondents rated child psychiatrists as relatively knowledgeable in management ethics, health care law, and formal negotiation skills. Fourteen respondents indicated they would make greater use of child psychiatrists in policy development, at least as part-time consultants, if they found child psychiatrists who were better trained in the areas covered in the survey.

Discussion and conclusions

Before discussing the results, potential weaknesses of the study must be noted. First, although survey responses were received from states that were geographically representative of major regions of the U.S., the moderate response rate may reflect a selection bias that limits the generalizability of the findings. Respondents with strong feelings on the subject may have been more likely to reply, which may have skewed the results. In addition, many surveys were completed by staff other than the department or service directors to whom the survey had been sent. Thus the survey responses should be interpreted as the opinions of the population who actually completed the survey.

Second, one must be cautious about making recommendations based on policy makers' perceptions of child psychiatrists. Perceptions may not reflect reality. However, these perceptions belong to key policy makers who control whether child psychiatrists have a "place at the table." If these perceptions are wrong, then child psychiatrists still must demonstrate that fact to the policy makers. A follow-up study that would examine respondents' experiences with child psychiatrists, including how long and how closely the respondents have worked with child psychiatrists and in what settings, could help clarify whether these perceptions are wrong.

Third, the results reflect a point-in-time snapshot of policy makers' opinions. Longitudinal surveys would be needed to determine if these perceptions of child psychiatrists are persistent in public mental health or are merely a transient finding reflecting the opinions of people in authority at this time. Finally, the survey instruments have not been standardized or otherwise tested. For the second survey, no comparative data showing how other disciplines would have fared in terms of actual or ideal levels of knowledge are available.

With these limitations in mind, the survey results can be used to paint a picture of the ideal child psychiatrist likely to be recruited to assist in public-sector policy development. This psychiatrist is a skilled clinician who is familiar with the strengths and weaknesses of common public-sector treatment options, such as family preservation programs, therapeutic foster homes, or wrap-around services. The psychiatrist is comfortable with using these services, rather than inpatient or long-term residential services, when a child's condition is deteriorating.

Although the ideal child psychiatrist understands how family dynamics may contribute to a child's psychopathology and may recognize the need for family members to change, he or she is willing to build on the family members' strengths in a culturally sensitive way and to redirect staff who focus on their weaknesses. The psychiatrist truly believes that usually, with the proper supports, the child will be better off with parents who have some flaws than in a residential institution.

Being sensitive to the professional dynamics of the organization, the ideal child psychiatrist can effectively negotiate with other professionals when there are differences of opinion and is a skilled, considerate manager of personnel. The psychiatrist stays informed about current general trends in health care administration, the law, and public health policy and looks for ways to apply them to public-sector concerns. The psychiatrist does not try to dodge administrative assignments, but accepts them willingly and works diligently on them with a view that such tasks are the price one pays to have a place at the policy table.

We have three recommendations to encourage the development of child psychiatrists who are more likely to be recruited for policy development work in the public sector. First, public child mental health services are increasingly being provided in mobile family preservation programs, family treatment homes, and other settings outside traditional clinics. Children in crisis are managed by mobilizing a flexible array of wrap-around services rather than by admitting them to a hospital. Child psychiatry residency programs need to ensure that trainees have a rotation in a public child psychiatry program, either as required curriculum or as an elective. Current accreditation standards for child psychiatry residencies do not include training in public-sector programs as a requirement (11). Practicing psychiatrists need to expand their familiarity with these new services and training strategies. Recent contributions in the literature reflect this trend (12,13).

Second, the administrative content of child psychiatric training programs must be broadened beyond discussions of managed care. This training should include a didactic series, provided throughout training, on personnel management, work motivation theory, quality improvement and outcomes measurement, financial management and budgeting, negotiation skills, public mental health systems, and organizational dynamics. Lectures should be supplemented by supervised administrative experiences, such as serving on a quality improvement committee, throughout training.

This preparation will produce child psychiatrists who are better equipped to assume both clinical and administrative leadership roles in settings that range from private practice to large public mental health systems. Current accreditation standards do not require any didactic content in administrative topics. Although accreditation standards for child psychiatry residencies require administrative experiences in which the residents function in positions of leadership, the standards are vague about what constitutes an adequate experience (11).

Some may argue a two-year training program is barely long enough to include the required clinical curriculum, without adding an expanded curriculum in administrative skills. It could also be argued that expanded administrative training should be provided in an administrative fellowship for those interested in management. However, in today's health care environment the administrative and business aspects of medicine permeate every part of mental health. Clinical psychiatrists without administrative skills run the risk of becoming little more than skilled workers who find that steadily greater degrees of their autonomy are taken from them by managers from other fields with such skills (14,15,16). Mental health care is not just a clinical profession any more. As distasteful as the idea may be, it is also a business. To ensure good patient care, psychiatrists must be fluent in the language of management.

Third and finally, child psychiatrists should consider it a privilege to be involved in the central planning of a public statewide system of care. Such work offers the chance to influence the mental health care of thousands of children. Child psychiatrists should not squander this opportunity, even if the financial compensation for this work is less than that for the same amount of time in other endeavors. As an alternative to employment of individual child psychiatrists in the central administration of public-sector systems, state delegations of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry could establish formal liaisons with their state department of mental health with the aim of providing ongoing input on children's mental health policy issues.

As public systems of care evolve, child psychiatry's influence on the direction they will take can be increased if child psychiatrists are better prepared to take on leadership roles in these systems. Child psychiatry residency programs can help improve child psychiatrists' potential for leadership by providing training about the wide range of treatment interventions and support services used in public-sector systems and by incorporating administrative topics and experiences into the curriculum throughout the residency. Child psychiatrists should be encouraged to consider it a privilege to be involved in planning a statewide system of care.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors for its assistance in distributing the surveys.

Dr. Soltys is the director of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health, P.O. Box 485, Columbia, South Carolina 29202 (e-mail, [email protected]). He is also professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine in Columbia. Mr. Wowra and Dr. Hodo are with the division of quality improvement and outcomes of the South Carolina Department of Mental Health. This paper was presented at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry held October 27 to November 1, 1998, in Anaheim, California.

|

Table 1. Respondents' ratings of actual and desired levels of skills and knowledge of child psychiatrists in 12 key areas for leadership in public-sector mental health systems1

1. Greenblatt M, Rose SO: Illustrious psychiatric administrators. American Journal of Psychiatry 134:626-630, 1977Link, Google Scholar

2. Diamond RJ, Stein LI, Scheider-Braus K: Administration: the psychiatrist as manager, in Integrated Mental Health Services: Modern Community Psychiatry. Edited by Breakey WR. New York, Oxford University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Lazarus A: The psychiatrist-executive revisited: new role, new economics. Psychiatric Annals 25:494-499, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Silver MA: Women in administrative psychiatry. Psychiatric Annals 25:509-511, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Rachlin S, Keill SL: Administration in psychiatry, in The American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Psychiatry, 2nd ed. Edited by Hales RE, Yudofsky SC, Talbott JA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994Google Scholar

6. Greenblatt M: The unique contributions of psychiatrists to leadership roles. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:260-262, 1983Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Keill SL: Strategies of influence: the psychiatrist-executive as political being. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 49:79-89, 1991Google Scholar

8. Rafferty FT:120 effects of health delivery systems on child and adolescent mental health care, in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 2nd ed. Edited by Lewis M. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

9. Pumariega A, Nace D, England MJ, et al: Community-based systems approach to children's managed mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies 6:149-164, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Stroul BA, Friedman RA: A System of Care for Children and Youth With Severe Emotional Disturbances, rev ed. Washington, DC, Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center, 1986Google Scholar

11. American Psychiatric Association: Directory of Psychiatric Residency Training Programs, 7th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

12. Meyers J, Kaufman M, Goldman S: Promising Practices for Serving Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances and Their Families in a System of Care. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Child, Adolescent, and Family Branch, 1998Google Scholar

13. Pumariega A, Diamond J, England MJ, et al: Guidelines for Training Towards Community-Based Systems of Care for Children With Serious Emotional Disturbances. Washington, DC, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1996Google Scholar

14. Haug MR: A re-examination of the hypothesis of physician deprofessionalization. Milbank Quarterly 66:48-56, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Light D, Levine S: The changing character of the medical profession: a theoretical overview. Milbank Quarterly 66:10-32, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Wolinsky NJ: The professional dominance perspective, revisited. Milbank Quarterly 66:33-47, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar