Obligatory Cessation of Smoking by Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Signs and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal and alterations in psychopathology were evaluated among acutely ill psychiatric patients admitted to a hospital with a smoking ban. It was hypothesized that smokers would experience symptoms of withdrawal and that these symptoms would aggravate and confound psychiatric symptoms. METHODS: Sixty acute psychiatric inpatients, 44 of whom were smokers, were assessed on three consecutive days using the Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist (NWC) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). RESULTS: BPRS scores were significantly and positively correlated from day 1 through day 3, as were NWC scores. Mean BPRS scores declined significantly from day 1 to day 3, and mean NWC scores declined significantly from day 1 to day 2. Although smokers reported increased tension over the three days and a greater persistence of anxiety compared with nonsmokers, no statistically significant differences in overall BPRS scores were found between the two groups. In contrast, symptoms of nicotine withdrawal occurred significantly more frequently among smokers and were statistically significantly correlated with scores on the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire, which assesses the degree of nicotine dependence. Despite subjects' reports of feeling distressed and of experiencing nicotine withdrawal symptoms, abrupt cessation of smoking did not significantly affect either the severity or the improvement of psychopathological symptoms during hospitalization. No specific diagnostic group appeared to be selectively sensitive to nicotine withdrawal symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: No immediate benefits or adverse effects from the smoking ban were detected. No compelling reasons to reverse the smoking ban were observed.

Rates of smoking are higher among psychiatric patients than in the general population (1,2,3,4). Reported rates of nicotine dependence for patients in treatment with a psychiatrist range from 40 to 100 percent (5). About 25 percent of adult Americans smoke, despite the recognition of associated health hazards (6). Smoking dependence has been attributed to many pharmacological and behavioral processes (7), including the withdrawal syndrome that some 80 percent of smokers develop when they stop smoking (8,9,10,11,12,13).

Although avoidance of withdrawal may be a compelling mechanism underlying continued smoking, certain psychiatric patients, such as those with schizophrenia (14), have difficulty stopping smoking, in part because they smoke to alleviate some of the uncomfortable side effects of psychotropic drugs (15). Cigarette smoking has been shown to increase the metabolism or clearance of psychotropic drugs (16,17,18,19,20), and patients with schizophrenia who smoke may receive higher doses of neuroleptics than nonsmokers (21,22,23).

Hospitals that instituted smoking bans in the 1980s anticipated many problems. However, only minimal impact on the efficacy of treatment was found (24,25,26,27). Nevertheless, 20 to 25 percent of psychiatric patients had difficulty adjusting to a ban (28).

The abrupt institution of a hospitalwide smoking ban afforded us an opportunity to examine nicotine dependence among psychiatric inpatients. We hypothesized that smokers would experience the same qualitative symptoms of withdrawal as nonpsychiatric populations and that the withdrawal would aggravate and confound their psychiatric symptoms.

Methods

Subjects were consecutively recruited between March 1991 and August 1992 on admission to inpatient psychiatric units at the Erie County Medical Center, a hospital of the State University of New York at Buffalo Medical-Dental Consortium. Ninety subjects were eligible to participate; 60 subjects were enrolled after giving informed consent.

Demographic information and smoking histories were obtained using detailed structured interviews. In addition to the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (29), a Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist (NWC) was administered. The NWC was prepared from a 17-item checklist of withdrawal symptoms to which an item about craving was added (10,13). Possible scores on the BPRS range from 18 to 26; higher scores indicate more, and more severe, signs and symptoms. Possible scores on the NWC range from 0 to 18; higher scores indicate more symptoms. The instruments were administered within 48 hours of recruitment to the study by raters blind to the smoking status of participants. They were readministered at approximately 24-hour intervals over the next two days.

The eight-item Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) was used to assess the degree of nicotine dependence (30,31). Possible scores range from 0 to 11, with higher scores indicating heavier and more frequent smoking. Subjects' use of nicotine chewing gum, their need for p.r.n medications, and occasions of seclusion and restraint were also recorded.

Results

We obtained useful data on 60 patients, 44 of whom were current smokers. Fifty-six patients (15 nonsmokers and 41 smokers, or 93 percent of the sample) completed the first two days of data collection. Forty-eight patients (15 nonsmokers and 33 smokers, or 80 percent of the sample) completed all three days. Those who didn't complete all three days were not significantly different from the completers in their FTQ, NWC, or BPRS scores.

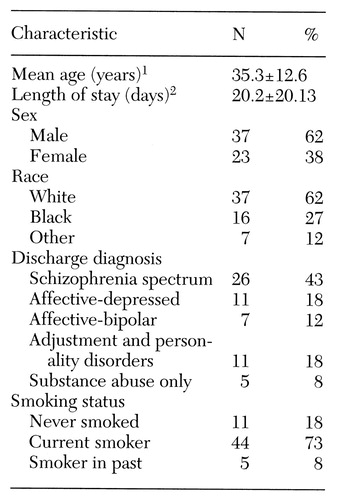

Diagnostic categories for the sample are shown in Table 1. Of 26 patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, one patient also had an adjustment or personality disorder and one a substance abuse disorder. In the affective-depressed group, three had concurrent substance abuse diagnoses, and one had an adjustment or personality disorder. It is interesting that a much lower proportion of this sample had an alcohol-related disorder compared with the rate of nearly 50 percent we found in a sample of similar patients (32,33,34).

Nearly three-fourths of the subjects were smokers. The prevalence of smoking ranged from 46 to 77 percent in the various diagnostic groups and did not vary significantly between groups. More than three-fourths of those in the schizophrenia-spectrum group and the affective-depressed group were smokers (77 and 82 percent, respectively); in the other groups about half of the patients were smokers.

Males and females did not differ significantly in mean length of hospital stay. The proportion of smokers among males and females was similar (73 and 70 percent, respectively), in contrast to a study by Goff and colleagues (22) that found a significantly higher rate of smoking among men.

In our study the length of hospital stay for nonsmokers was 28.5 days, nearly twice that of the smokers, which was 17 days (t=1.99, df=58, p=.052).

Ten of the 44 smokers received nicotine gum, nine of whom chose to use it only once or twice. Exclusion of the only patient who chewed the gum on a regular basis did not affect the conclusions of the various statistical analyses. The amounts of gum used were unlikely to have had a detectable effect on withdrawal symptoms (8).

FTQ scores

FTQ scores, which indicated the degree of nicotine dependence, ranged from 0, among the nonsmokers, to 10. Smokers' FTQ scores ranged from 2 to 10, out of a possible maximum score of 11 (median=6, mean±SD= 6.27±2.13).

BPRS scores

On the first day, the mean±SD BPRS score of nonsmokers (33.8±9.8) was higher than that of smokers (31.8±7.01), although the difference was not statistically significant. On the second and third days, the mean scores of the nonsmokers (32.7±11.6 and 32.9±11.6, respectively) were also higher than those of the smokers (29.4±6.7 and 27.97±6, respectively), but these differences between smokers and nonsmokers were also not significant.

The mean BPRS scores for both groups declined significantly from day 1 to day 2 and from day 1 to day 3, but the decreases were smaller for the nonsmoking group. For the smokers the mean BPRS scores on the second and third days (29.4 and 27.9, respectively) were significantly lower than the score of 31.8 on the first day (paired t=3.01, df=43, p=.004, for the second day; t=4.57, df=31, p<.001, for the third day).

BPRS scores on consecutive days were positively correlated—both from day 1 to day 2 (r=.77, p=.001) and from day 2 to day 3 (r=.54,p=.001)—demonstrating consistency in individual patients' psychopathology over the three days relative to that of other patients.

Among smokers, BPRS scores and the decreases in scores over the three days were not significantly different with respect to diagnosis as measured by a one-way analysis of variance.

On the first day, nonsmokers had appreciably higher scores than smokers on the BPRS items for anxiety and emotional withdrawal, although these differences were not statistically significant. On the other hand, smokers had higher mean scores than nonsmokers on the BPRS items measuring hostility and tension, which were also not significant differences.

Among all patients, the scores on BPRS items that decreased the most from day 1 to day 2 were for anxiety, conceptual disorganization, depressive mood, excitement, hostility, and hallucinations. The decrease in the mean score for the anxiety item was greater for nonsmokers than for smokers (a decrease of .08 versus .14) but the difference was not significant.

Among the nonsmokers, the most marked decreases in the mean scores on individual BPRS items were for anxiety and depressive mood. The most striking difference between smokers and nonsmokers between day 1 and day 2 was on the hostility item; the smokers' mean score decreased by .52 (paired t=1.88, df=43, p=.001), while the nonsmokers' mean score actually increased slightly by .13. In contrast, the smokers' score on the tension item increased from day 1 to day 3, while among nonsmokers it decreased. This difference was not significant. Nevertheless, the increase in tension over the three days and the greater persistence of anxiety among smokers, compared with the decreases on both items among nonsmokers, may have been a reflection of nicotine withdrawal in the smoking group.

NWC scores

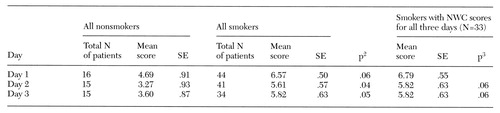

Table 2 presents results for the Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist. Although NWC scores were positively correlated from day 1 to day 2 (r=.78, p=.001) and from day 1 to day 3 (r=.70, p=.001), they declined significantly from day 1 to day 2 and from day 1 to day 3, which reflected decreases in the intensity and number of withdrawal symptoms over the three days.

As anticipated, smokers exhibited more symptoms characteristic of nicotine withdrawal than did nonsmokers (for day 1, mean NWC scores were 6.57 and 4.69, respectively). Decreases in NWC scores over the three days were more marked for the nonsmokers than for the smokers.

Among the individual NWC items, one item—craving for cigarettes—was expected to be different between groups; all but four of the smokers cited it on the first day, while none of the nonsmokers did (χ2=43.6, df=1, p<.001). The NWC items most frequently cited by smokers on the first day were anxiety and tension, cited by 25 smokers (57 percent); restlessness, cited by 24 (55 percent); depression, cited by 22 (50 percent); irritability, cited by 20 (46 percent); and impatience and excessive hunger, cited by 18 each (41 percent). On the second day, the only NWC item cited more frequently by smokers than by nonsmokers was craving (χ2=21.7, df=2, p<.001).

Correlations between scale scores

Reliability analyses showed the BPRS and the NWC scales to be reliable tests. We also examined an extensive matrix of correlations of total scores on the scales and scores on the individual items on each scale, as suggested for this type of study (35). Most items had only modest to low correlations with other items, suggesting that the majority of them were in fact tapping into different symptoms or dimensions.

Among the few clear associations was the finding that among smokers the FTQ score was significantly correlated with the NWC score (r=.36, p=.01). Among individual items, two NWC items—craving for cigarettes and restlessness—were correlated with the FTQ score (for craving, r=.38, p=.01; for restlessness, r=.36, p=.01). Among the FTQ items, item 6 ("Do you smoke if you are so ill that you stay in bed?") was most highly correlated with the total NWC score. No significant correlations or associations between the FTQ score and changes in the NWC or BPRS over the three days were detected by chi square analysis.

Compared with smokers with schizophrenia and with all other subjects, the eight smokers with depression and the four with bipolar disorder were not more psychiatrically disturbed as measured by the BPRS nor did they suffer greater nicotine withdrawal. These findings are in contrast to those of Glassman and associates (36). Despite some apparent overlap in the names of items on the BPRS and the NWC, none of the BPRS items were significantly correlated with NWC items.

Discussion and conclusions

A change in hospital policy presented the opportunity to examine the effects of sudden cessation of smoking on symptoms in a population of patients admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit. We expected to observe a change in psychopathology occasioned by forced alterations in smoking habits. Although nonsmokers had higher BPRS scores, we failed to find statistically significant differences between smokers and nonsmokers in the mean BPRS scores. Scores on the BPRS, which assesses many dimensions of psychopathology, were highest for both smokers and nonsmokers during the first 48 hours after admission and declined significantly thereafter for both groups. These results are consistent with the beneficial effects of hospitalization, benefits that may have exceeded the negative effects of nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

As expected, Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist scores were consistently higher for smokers, and scores decreased for both groups from the first to the second day of observation. No significant correlation was found between psychiatric symptoms as measured by the BPRS and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. Furthermore, measures of nicotine dependence (the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire), which did correlate with withdrawal symptoms, also failed to show a significant correlation with the BPRS score, indicating the absence of a strong relationship between the degree of dependence on nicotine and patients' psychiatric symptoms, a finding that has been reported previously (11,13,15). Nevertheless, the overlap between symptom complexes of psychiatric illness and nicotine withdrawal poses significant issues for diagnosis and management (37).

The NWC withdrawal symptoms assessed were the same as those studied by Gritz and associates (10). Compared with their sample, a higher percentage of our subjects cited each of the various symptoms. However, we found the same items to be the most frequently cited, with the exception of depression—only 16 percent of the subjects in their study cited depression, compared with 50 percent of our subjects.

Our initial concern that nicotine withdrawal would aggravate psychiatric symptoms was not borne out, which has been the experience of other investigators (24,25,26,28,38). However, unlike others (25), we failed to observe any positive effects that could be attributed to the smoking ban. Although our subjects were not in favor of the ban, most became resigned to it, as has been noted in other studies (38).

Dr. Smith is professor in the department of pharmacology and toxicology at the School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of the State University of New York at Buffalo, 102 Farber Hall, Main Street Campus, Buffalo, New York 14214 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Pristach is associate clinical professor and Dr. Cartagena is a resident and clinical instructor in the department of psychiatry at the school. Dr. Pristach is also unit chief at the Erie County Medical Center in Buffalo.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 60 psychiatric inpatients admitted to a hospital with a smoking ban

1 Range, 17 to 85 years

2 Range, 2 to 103 days

|

Table 2. Mean scores over three consecutive days on the Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist (NWC) of 60 psychiatric inpatients admitted to a hospital with a smoking ban1

1 Scores indicate the number of nicotine withdrawal symptoms reported.

2 For comparison (t test) of all nonsmokers with all smokers

3 For comparison (paired test) with day 1 score

1. Moriarty K, Wagner J: Highlights of the 40th Institute on Hospital and Community Psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:113-118, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bronaugh TA, Frances RJ: Establishing a smoke-free inpatient unit: is it feasible? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1303- 1305, 1990Google Scholar

3. Hughes JR: Possible effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:109-114, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

4. Glassman AH: Cigarette smoking: implications for psychiatric illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:546-553, 1993Link, Google Scholar

5. Cocores JA: Nicotine addiction, in The Comprehensive Handbook of Drug and Alcohol Addiction. Edited by Miller NS. New York, Marcel-Dekker, 1990Google Scholar

6. Cigarette smoking among adults, United States 1992, and changes in the definition of cigarette smoking. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 43:342-346, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

7. Stolerman IP, Shoaib M: The neurobiology of tobacco addiction. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 12:467-473, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Benowitz NL: Pharmacological aspects of cigarette smoking and nicotine addiction. New England Journal of Medicine 319:1318-1330, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Benowitz NL: Pharmacology of nicotine. Annual Review of Pharmacology 36:597-613, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Gritz ER, Carr CR, Marcus AC: The tobacco withdrawal syndrome in unaided quitters. British Journal of Addiction 86:57-69, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cummings KM, Giovino G, Jaen CR, et al: Reports of smoking withdrawal symptoms over a 21-day period of abstinence. Addictive Behaviors 10:373-381, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hughes JR, Hatsukami D: Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:289-294, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Gritz ER, Carr CR, Marcus AC: Unaided smoking cessation: Great American Smokeout and New Year's Day quitters. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 6:217-234, 1988Google Scholar

14. DeLeon J: Smoking and vulnerability for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:405-409, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Dingman P, Resnick M, Bosworth F: A nonsmoking policy on an acute psychiatric unit. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 26:11-14, 1988Google Scholar

16. Jusko WJ: Influence of cigarette smoking on drug metabolism in man. Drug Metabolism Reviews 9:221-236, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Schein JR: Cigarette smoking and clinically significant drug interactions. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 29:1139-1148, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Jann MW, Saklad SR, Ereshefsky LO, et al: Effects of smoking on haloperidol and reduced haloperidol plasma concentrations and haloperidol clearance. Psychopharmacology 90:468-470, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Miller DD, Kelly MW, Perry PJ, et al: The influence of cigarette smoking on haloperidol pharmacokinetics. Biological Psychiatry 28:529-531, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Watanabe MD, et al: Thiothixene pharmacokinetic interactions: a study of hepatic enzyme inducers, clearance inhibitors, and demographic variables. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 11:296-301, 1991Google Scholar

21. Decina P, Caracci G, Sandik R, et al: Cigarette smoking and neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism. Biological Psychiatry 28:502- 508, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Goff DC, Henderson DC, Amico E: Cigarette smoking and schizophrenia: relationship to psychopathology and medication side effects. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1189-1194, 1992Link, Google Scholar

23. Ziedonis DM, Kosten TR, Glazer WM, et al: Nicotine dependence and schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:204- 206, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Thorward SR, Birnbaum S: Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric unit. General Hospital Psychiatry 11:63-67, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Smith WR, Grant BL: Effects of a smoking ban on a general hospital psychiatric service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:497- 502, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Resnick MP, Bosworth E: A smoke-free psychiatric unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:525-527, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

27. Parks JJ, Devine DD: The effects of smoking bans on extended care units at state psychiatric hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:885-886, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Greeman M, McClellan TA: Negative effects of a smoking ban on an inpatient psychiatry service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:408-412, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Fagerstrom K: Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addictive Behaviors 3:235-241, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Fagerstrom K, Schneider NG: Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 12:159-182, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Pristach CA, Smith CM: Medication compliance and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1345-1348, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Smith CM, Pristach CA: Utility of the Self-Administered Alcoholism Screening Test (SAAST) in schizophrenic patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 14:690-694, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Pristach CA, Smith CM: Self-reported effects of alcohol use on symptoms of schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:421-423, 1996Link, Google Scholar

35. Norusis MJ: The SPSS Guide to Data Analysis for SPSS/PC+, 2nd ed. Cary, NC, SPSS Inc, 1991Google Scholar

36. Glassman AH, Covey LS, Dalack GW, et al: Smoking cessation, clonidine, and vulnerability to nicotine among dependent smokers. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 54:670-679, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Hughes JR: Possible side effects of smoke-free inpatient units on psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 54:109-114, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

38. Haller E, McNeil DE, Binder RL: Impact of a smoking ban on a locked psychiatric unit. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:329-332, 1996Medline, Google Scholar