Quality of Life, Loneliness, and Social Contact Among Long-Term Psychiatric Patients

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Long-term patients who resided in county-operated psychiatric nursing homes in a county in Norway as of November 15, 1989, were visited by researchers in 1996 to assess how they perceived their living situations and how they had adjusted to a large reduction in county psychiatric beds during the six-year period. METHODS: Of 107 patients identified in 1989, a total of 75 were still alive in 1995. Seventy-four took part in the study and were visited at their place of residence. Thirty patients were living in general nursing homes, 23 patients remained in the psychiatric nursing homes, and 21 patients lived outside of institutions, in a personal residence. The quality of the patients' contact with others was rated by health care providers who were familiar with the patients. Forty-two patients, with a mean age of 56.9 years, responded to personal questions about their life situation, loneliness, and quality of life. RESULTS: Health care providers constituted the patients' most important network. Patients outside of institutions were the most socially active and had the most satisfying contact with their families. Patients reported a satisfactory quality of life, and those who lived outside institutions tended to be most satisfied. The variables of loneliness, satisfaction with neighborhood, and leisure time activities explained 63 percent of the variance in patients' subjective well-being. CONCLUSIONS: Most long-term patients who had moved out of psychiatric institutions were satisfied with their living situation and reported a relatively high quality of life.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Norway's large psychiatric institutions have been reduced in size. The goal has been to provide decentralized care with emphasis on patients' normalization and integration into the community to improve patients' quality of life.

Long-term patients with psychotic disorders are reported to have a lower quality of life than the general population (1,2). Some reports indicate that long-term patients experience loneliness after discharge from institutions (3,4). Few studies have addressed the circumstances of the oldest patients with the most chronic course of illness (5,6), and little reliable information exists about whether self-report scales for assessing quality of life may be used in a meaningful way with these patients.

This study examined various aspects of the quality of life of chronic patients six years after a large reduction in the number of psychiatric beds in Norway. The study examined differences in quality of life among patients with different levels of care and sought to answer the following questions: To what degree did the patients have contact with close others, such as family and friends, and were they satisfied with this contact? Were patients able to respond to questions about their personal experiences and quality of life? To what extent did they feel lonely? How did patients rate their quality of life, and is it possible to identify variables that could explain variations in quality of life?

Methods

Patients

In the last 20 years, many patients have been discharged to the community from two large psychiatric nursing homes located in the rural county of Sogn and Fjordane in Norway. On November 15, 1989, a total of 107 long-term patients remained in the institutions. All of them had spent at least one year there, and 70 percent had been living in the institutions for ten years or more. These 107 patients constituted the entire population of long-term inpatients in the county as of that date, and they accounted for .1 percent of the total population of the county catchment area (7).

At follow-up six years later, many patients had moved back to their community of origin after planned discharges. Thirty-two patients had died. Those who had died were significantly older in 1989 than those who survived (mean±SD=68.7±13.9 years, compared with 53.4±15.3 years; t=4.87, df=105, p<.001). The mean age at death for the patients who had died was 10.5 years below the life expectancy for the general population.

Of the 75 patients who were alive at the time of the follow-up, one patient did not want to participate in the study. The remaining 74 patients included 54 men and 20 women with a mean±SD age of 60.4±14 years. Sixty-nine percent met criteria for a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia. Eighty-four percent had never been married. Thirty patients, or 41 percent, were living in general nursing homes; 23 patients, or 30 percent, remained in the county-run psychiatric nursing homes; and 21 patients, or 29 percent, lived outside of institutions in a personal residence. All except three patients had regular contact with the health care system (8).

Study procedure

The research protocol was approved by the regional ethical committee for medical research. Local health care providers asked the patients to take part in the study. All patients were visited by a member of the research team between January and June 1996. The team included two psychiatrists, one resident, one psychologist, and two psychiatric nurses.

Sociodemographic data were obtained from local health care providers who knew the patients well using a questionnaire that included questions on the patient's life situation and contact with others.

Each patients' level of symptoms was measured by a research team member using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), expanded version 3.0. (9). Higher scores on the BPRS indicate more severe symptoms. Level of functioning was assessed using the Rehabilitation Evaluation of Hall and Baker (REHAB) (10), on which higher scores indicate worse functioning, and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (11), on which higher scores indicate better functioning. Twenty patients were interviewed by one member of the research team in the presence of the others, who also rated these patients on the REHAB, BPRS, and GAF. The intraclass coefficients were above .9 for all subscales and total scores (12).

How often patients felt lonely was scored on a 5-point self-report scale on which 1 represented never; 2, seldom; 3, sometimes; 4, often; and 5, very often. Quality of life was assessed using a 14-item self-report questionnaire based on an instrument developed in Norway by Sørensen and Næss (2). The first three questions asked respondents to rate on a scale from 1 to 7 how happy or unhappy or how satisfied or dissatisfied they felt and how encouraging or disappointing life was at the moment. The scores on these three questions were strongly intercorrelated (r values ranged from .56 to .69, p<.01). In the data analysis, these questions were combined into one variable called subjective well-being. This new variable was strongly correlated with the three original variables (r values ranged from .82 to .87, p<.001).

The fourth question asked respondents to rate their present level of happiness using Cantril's Self-Anchoring Ladder, a ten-point scale anchored by respondents' own identified values (13). The remaining ten questions asked patients to rate their satisfaction with various life domains on a scale from 1 to 7.

Data were analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 7.0. T tests, Pearson's r correlation analyses, chi square tests, and discriminant and linear regression analysis were used. The level of significance for all tests was .05 if not otherwise stated.

Results

Contact with others

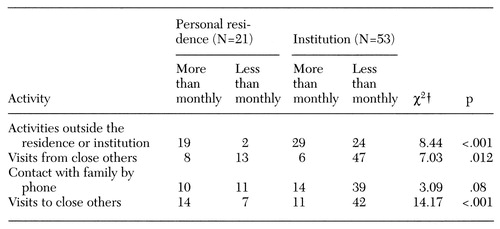

Local health care providers reported that patients who were living outside institutions had significantly more contact with family and friends and were the most socially active (Table 1). For 42 patients, or 56 percent, the contact was qualitatively good. Thirty-two patients, or 44 percent, had bad contact or no contact with family and friends; 28 of these 32 patients were living in institutions. Health care staff were the most important persons in the social network of 56 patients, or 76 percent.

Responses to personal questions

Only 42 patients, or 56 percent, were able to answer the self-report questions about quality of life. This group, which included 29 men and 13 women, were on average younger than the patients who did not answer the questions (mean age=56.9±15 years, compared with 65±14.5 years; t=2.74, df=72, p<.01). Nineteen of the 21 patients living outside institutions answered, compared with 23 of the 53 patients living in institutions (χ2=11.7 [with continuity correction], df=1, p<.01).

Those who answered the self-report questions had a lower level of symptoms than those who did not answer (mean score of 1.8±.6 on the BPRS, compared with 2.2±.6; t=3.45, df=72, p<.05). Those who answered also had a higher level of functioning than those who did not answer (mean score of 2.9±1.9 on the REHAB, compared with 5.4±2.2; t=5.96, df= 72, p<.05; and mean score of 32±10.8 on the GAF, compared with 21±9.5; t=4.82, df=72, p<.05). Although respondents' level of functioning was higher than that of nonrespondents, it was still low and was lower than what would be expected based on their low level of symptoms.

Loneliness

Eighteen patients, or 43 percent of those who responded to the self-report questions, never or seldom felt lonely, and 19 patients, or 46 percent, sometimes felt lonely. Five patients, or 12 percent, felt lonely often or very often; four of those patients lived in institutions. The correlation between this score and the BPRS measure of depression was .52 (p<.01).

Quality of life

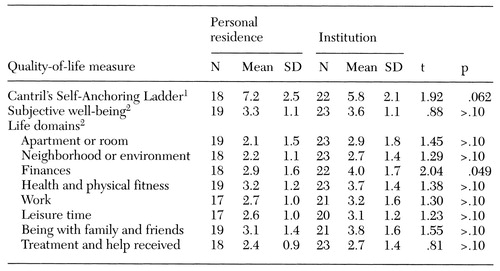

Mean scores on all items measuring quality of life indicated that patients felt they had a relatively high quality of life (Table 2). The difference in perceived quality of life between the patients who lived in personal residences and those who lived in institutions was statistically significant for only one of the life domains, finances. Discriminant analysis did not show significant differences between the groups. When all ten measures were considered together, the mean score of the personal residence group indicated higher overall satisfaction (binomial probability, p<.001).

Subjective well-being was strongly negatively correlated with degree of loneliness (r=−.64, p<.001) and was moderately to strongly positively correlated with the various life domains (r values ranged from .34 to .64, p<.05). The correlation was strongest for leisure time activities (r=.64), neighborhood (r=.62), apartment or room (r=.59), and treatment or help (r=.57). Subjective well-being was only weakly correlated with mean scores on the BPRS, REHAB, and GAF (r values ranged from .02 to .13).

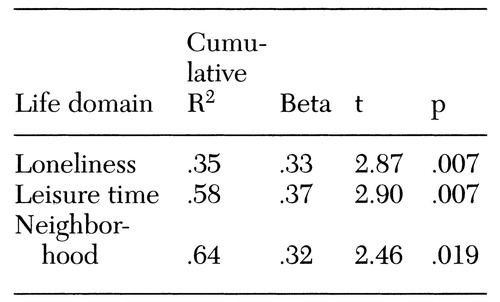

A hierarchical multiple regression analysis revealed that feeling lonely explained 35 percent of the variance in subjective well-being. Leisure time activities increased the explained variance by another 23 percent, and quality of the neighborhood by an additional 6 percent. Together these three variables explained 64 percent of the variance (Table 3). All three variables made significant and independent contributions. The BPRS measure of depression did not enter the equation.

Discussion

Patients who had moved out of the institutions were more socially active and had more contact with their families, but among all subjects emotional and practical support were more likely to come from health care staff than from family or friends. These findings correspond well with those of other studies showing that the primary social networks of patients with chronic psychotic disorders are small (14,15).

About half of the patients felt lonely; however, loneliness was not more pronounced among patients who lived on their own. Loneliness is described as one of the most fundamental problems of patients with schizophrenia, but studies examining loneliness and social isolation among these patients are comparatively few (16). The findings of Neeleman and Power (17) that psychotic patients with large social networks often feel as lonely as those without correspond well with our findings.

Despite their serious, chronic disease, in general the study patients were satisfied with their quality of life. In other studies involving younger patients, subjects have reported general dissatisfaction (18,19). Long-term illness may have reduced the expectations of the patients in our study, and this outlook may explain their relatively high level of satisfaction. Patients living outside institutions tended to report a higher quality of life and to be more satisfied, a finding corresponding well with studies of MacGilp (20) and Gråwe and Løvaas (19). Quality of life was more dependent on meaningful leisure time activities and good relations with the neighborhood and environment than on the level of symptoms and functioning. These findings support those of other studies (5) and should be taken into account when planning services for chronic mental patients.

A disadvantage of a study design that involves asking severely disturbed patients personal questions about their quality of life is the low response rate. In our study, most of the patients who were living outside institutions responded, and the study results seem to represent this group of younger, better-functioning patients. How best to assess the experience of older, most disturbed patients is an open question. Staff and patient evaluations often do not agree, and objective measures bear at best modest relationships to life satisfaction (21). Therefore, the use of staff evaluations alone has limited value.

The cross-sectional nature of our study permits only the generation of hypotheses about which interventions might enhance the quality of life of these patients. Clarification of causal relationships must await longitudinal interventions. Almost one-third of the patients had died during the follow-up period, and almost half of the survivors were not able to respond to personal questions. These factors limit the extent to which the results can be generalized. On the other hand, very few studies have examined the experience of older, most severely disturbed patients, and the study findings therefore add information about this population to the literature.

Conclusions

Six years after an initial assessment of a group of long-term institutionalized psychiatric patients, most patients remained in institutions, the majority in general nursing homes. About half of the patients were able to answer personal questions about their quality of life. In general, patients were satisfied with their situation and reported a relatively high quality of life. Degree of loneliness, meaningful leisure time activities, and satisfaction with the neighborhood were the variables that best explained the variance in subjective well-being. Health care professionals were the most important persons in the patients' social networks.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Roald Kalstad, R.M.N, and Anna Karin Skrede for help in interviewing patients. The study was supported by the Norwegian Council for Mental Health.

Ms. Borge is assistant professor on the Faculty of Health Studies, College of Sogn and Fjordane, N-6800 Førde, Norway (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Martinsen is medical director and Dr. Watne is a resident in the department of psychiatry at Central Hospital in Førde. Dr. Ruud is medical director at Nordfjord Psychiatric Center in Nordfjordeid, Norway. Dr. Friis is professor in the department of psychiatry at Ullevål University Hospital in Oslo.

|

Table 1. Ratings by health care staff of the frequency of activities of long-term psychiatric patients living in a personal residence or institution

† df=1

|

Table 2. Self-reported quality of life of long-term psychiatric patients residing in a personal residence or institution

1 Measures respondent's perception of level of personal happiness on a scale from 1, worst possible, to 100, best possible

2 Measured on a scale from 1, very satisfied, to 7, very satisfied

|

Table 3. Multiple regression analysis of variance in the subjective well-being of long-term psychiatric patients (N=42)

1. Lehman AF, Ward N, Linn L: Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1271- 1276, 1982Link, Google Scholar

2. Sørensen T, Næss S: To measure quality of life: relevance and use in the psychiatric domain. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 37 (suppl):29-39, 1996Google Scholar

3. Lehman AF, Possidente S, Hawker F: The quality of life of chronic mental patients in a state hospital and community residences. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:901-907, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Pinkney AA, Gerber J, Lefave HG: Quality of life after psychiatric rehabilitation: the clients' perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 83:86-91, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF: The well-being of chronic mental patients: assessing their quality of life. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:369- 373, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Okin RL, Pearsall D: Patients' perceptions of their quality of life 11 years after discharge from a state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:236-240, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Ruud T, Martinsen EW, Friis S: Chronic patients in psychiatric institutions: psychopathology, level of functioning, and need of care. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97:55-61, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Martinsen EW, Ruud T, Borge L, et al: The fate of chronic inpatients after closure of nursing homes in Norway: a personal follow-up six years after. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 98:360-365, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, Expanded Version 3.0. University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Clinical Research Center for Schizophrenia, 1992Google Scholar

10. Baker R, Hall JN: Users' Manual for the Rehabilitation Evaluation of Hall and Baker. Aberdeen, Scotland, Vine, 1986Google Scholar

11. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

12. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin 86:420-428, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Cantril H: The Pattern of Human Concerns. New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers University Press, 1965Google Scholar

14. Cresswell CM, Kuipers L, Power MJ: Social networks and support in long-term psychiatric patients. Psychological Medicine 22:1019-1026, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Davidson L, Hoge MA, Godleski, L, et al: Hospital or community living? Examining consumer perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:49-58, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

16. West DA, Kellner R, Moore-West M: The effects of loneliness: a review of the literature. Comprehensive Psychiatry 27:351- 363, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Neeleman J, Power MJ: Social support and depression in three groups of psychiatric patients and a group of medical controls. Social Psychiatry and Epidemiology 29:46- 51, 1994Google Scholar

18. Skantze K, Malm U, Dencher SJ, et al: Quality of life in schizophrenia. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 44:71-75, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Gråwe R, Løvaas AL: Quality of life among schizophrenic in- and out-patients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 48:147-151, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

20. MacGilp D: A quality of life study of discharged long-term psychiatric patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing 16:1206- 1215, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Sainfort F, Becher M, Diamond R: Judgments of quality of life of individuals with severe mental disorders: patient self-report versus provider perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:497-502, 1996Link, Google Scholar