Datapoints: The Structure of Psychiatrists' Outpatient Practice

Across all of medicine an increasing proportion of physicians have been working in group practice. The American Medical Association reported a 166 percent increase in the number of physicians in group practice between 1980 and 1996 (1). In 1996 only 29 percent of office-based physicians reported their primary employment as self-employed solo practice (1).

In 1996 a total of 970 members of the American Psychiatric Association completed the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP), a study designed to provide representative national data on the aggregate demographic and practice characteristics of psychiatrists and their patients (2). Psychiatrists completing the NSPP were asked to indicate specifically the outpatient care setting where they worked the greatest number of outpatient hours—individual practice, psychiatric group practice, multidisciplinary mental health group practice, or multidisciplinary general medical and mental health group practice—or whether they did not work in an outpatient setting. A total of 889 psychiatrists responded to this question, of whom 847 (95 percent) reported working in an outpatient setting. This column summarizes the demographic and practice characteristics of psychiatrists providing outpatient care.

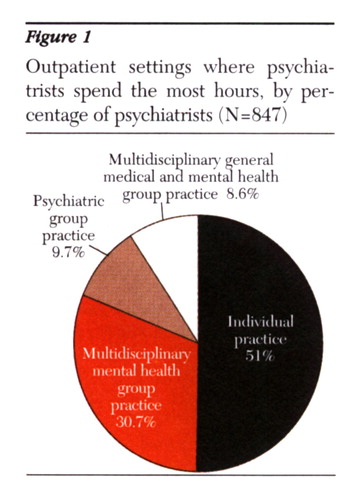

Figure 1 shows the outpatient settings where psychiatrists spend the most hours. The percentage of psychiatrists in an individual practice was approximately equal to the percentage in group practice. Of the psychiatrists working in group practice, the majority were in a multidisciplinary mental health group practice.

Female psychiatrists were more likely than male psychiatrists to spend the greatest number of their outpatient care hours in group practice. Psychiatrists age 39 years and younger were also more likely than those age 55 and older to spend the most hours in a group practice.

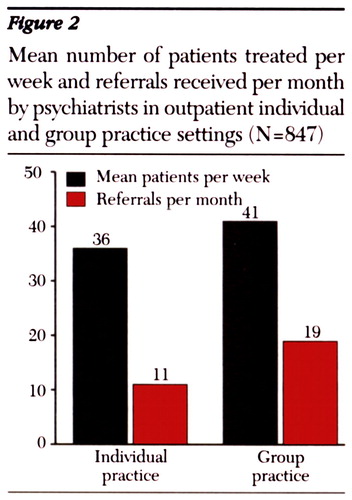

As Figure 2 shows, psychiatrists in group practice treated more patients per week than those in individual practice and had almost twice the number of referrals per month. The larger number of patients treated by psychiatrists in group practice may reflect differences in practice styles between the two settings; for example, private solo office practitioners may treat patients over longer periods of time and thus may have fewer openings, and psychiatrists in group practice may have more referral sources available.

The NSPP will be conducted periodically to examine the changing patterns of outpatient psychiatric practice. More detailed studies are needed to further understand the specific relationship between psychiatrists' outpatient care settings and the types of patients, treatments, and outcomes associated with each setting.

The authors are affiliated with the office of research of the American Psychiatric Association, 1400 K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005. Dr. Pincusand Terri L. Tanielian, M.A., are coeditors of this column.

Figure 1. Outpatient settings where psychiatrists spend the most hours, by percentage of psychiatrists (N=847)

Figure 2. Mean number of patients treated per week and referrals received per month by psychiatrists in outpatient individual and group practice settings (N=847)

1. Physician Characteristics and Distribution in the US. Chicago, American Medical Association, Department of Data Survey and Planning, Division of Survey and Data Resources, 1997-98Google Scholar

2. Zarin DZ, Pincus HA, Peterson BP, et al: Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:397-404, 1998Link, Google Scholar