Best Practices: Use of a New Outcome Scale to Determine Best Practices

Efforts to control health care costs and to encourage health care reform have led to increasing demand for quantitative measurement of the effectiveness of behavioral health treatment. Outcomes must be used to inform stakeholders, including consumers, clinicians, and managers, about treatment-related gains to be useful in improving patient services. Best-practices benchmarking using outcome data has become important for both clinical practice and policy making in the U.S. and in other countries (1,2,3,4,5,6).

The program evaluation described in this paper assessed treatment outcomes in the areas of quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning for a cohort of outpatients one year after they began treatment at a university psychiatric clinic. The patients' satisfaction with treatment was also assessed, and data on several demographic and clinical variables were collected to explore possible contributing factors to treatment gains.

Few follow-up studies describing the gains patients make in naturalistic treatment settings have been done (7). The quasiexperimental design without a control group and without random assignment used in this study does not allow conclusions to be drawn about causes of gains, but it can assess whether gains are made in important life areas and how these gains are related to patients' satisfaction with the services they received.

Evaluation procedures

All new patients who came to the University of Missouri psychiatric outpatient clinic during 1995 (N=200) were given the Treatment Outcome Profile at intake. The patients were mailed a follow-up profile form to complete about one year later. The profile form completed at admission contained 27 self-report items, divided among three major scales that measure quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning. Responses to items were marked on 5-point Likert-type scales, on which higher scores indicated better quality of life, reduced symptoms, and better functioning. The form used at follow-up measured these three major areas and also included a scale that measured patient satisfaction. Responses to items associated with the satisfaction scale were marked on a 5-point scale on which higher scores indicated more satisfaction. (A copy of the Treatment Outcome Profile is available from the first author.)

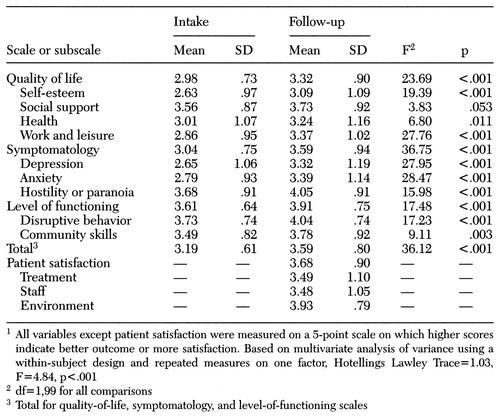

Each of the major scales encompassed two to four subscales (see Table 1). Details about the internal reliability and criterion validity of the Treatment Outcome Profile for use with psychiatric and substance abuse inpatients are published elsewhere (8). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (9) and the Zung Anxiety Scale (10) were also given at intake but not at follow-up.

Of the original sample of 200 new patients, 144 had legitimate addresses on record at the time of follow-up. One hundred forms were returned after three mailings plus telephone calls asking for help in returning the forms. Therefore, a return rate of 69 percent of those with legitimate addresses was achieved, with a 50 percent overall return rate. No statistical differences on dependent variables were found between patients who returned forms and those who did not, except that those who returned forms had more health concerns, as measured by the health subscale of the Treatment Outcome Profile.

At the time of the study, the university clinic that was the study setting provided about 450 adult treatment episodes of care per month. The majority of patients were employees of the university or government agencies who were provided outpatient psychiatric services under managed care contracts.

Of the 100 subjects with follow-up data, 71 were women, and 29 were men. Ninety-one percent were Caucasian. The average age was 43 years. The average number of visits per subject during the study period was 5.6. Patients were seen by attending psychiatrists, resident psychiatrists, and doctoral-level psychologists. The primary modes of treatment were psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and referral to other agencies for supportive social services.

The most frequent DSM-IV primary diagnosis was major depression, for 40 patients, followed by dysthymia, for 24 patients, and panic disorder, for 14 patients. Other diagnoses included adjustment disorder, six patients; anxiety, six patients; bipolar disorder, five patients; alcohol and drug abuse, three patients; and schizophrenia, two patients.

Results

Total scores on the BDI and the Zung Anxiety Scale at intake were highly correlated with all scales and subscales of the Treatment Outcome Profile at intake, thus demonstrating the profile's construct validity. The BDI correlated most highly with the symptomatology scale (r=-.66), the total score for the profile (r=-.69), and the depression subscale (r=-.58). The Zung Anxiety Scale had high correlations with the total score for the profile (r=-.61), the symptomatology scale (r=-.58), and the anxiety subscale (r=-.64).

Table 1 presents comparisons of measures of dependent variables at intake and one-year follow-up. All scales and subscales of the Treatment Outcome Profile showed significant gains over the study period. Seventy-three patients reported positive gains in total scores on the profile one year after receiving treatment. (Scores on the satisfaction scale were not included in figuring the total scores for the Treatment Outcome Profile at follow-up.) The most sensitive measures—those with high F values and largest gains—were the symptomatology scale, the total score, the anxiety subscale, the depression subscale, the work and leisure subscale, and the quality-of-life scale.

To further explore variables related to one-year follow-up, stepwise multiple regression was used to predict the overall gain in total scores (11). Thirteen independent variables were included in the multiple regression. They were number of treatment sessions, whether the patient saw only a psychiatrist or a psychiatrist and a psychologist, satisfaction with treatment, satisfaction with staff, satisfaction with the treatment environment, time between the intake and follow-up measures, a diagnosis of depression, a diagnosis of panic disorder, the clinician's level of experience, source of referral (self or a physician), whether the patient was prescribed medications, gender, and age.

Only satisfaction with treatment (p=.003) and age (p=.01) were significant and were retained in the final model (F=7.43, p=.001, R2=.138). Patients who had higher satisfaction ratings and who were younger tended to report greater overall treatment gains. Patients who were self-referred tended to have greater self-reported gains, but the difference was not significant. This model accounted for only 13.8 percent of the total variance of overall treatment gain. Clearly changes in the person's life, such as marriage, work, and traumatic stresses, may have had additional influences on psychological well-being of the patients during treatment, but these variables were not assessed in this study.

Because satisfaction with treatment was directly related to treatment gain, stepwise multiple regression was again used to explore variables that could predict satisfaction with treatment. All of the clinical and demographic variables previously mentioned were included in the analysis except the satisfaction variables. A one-variable model was produced, with number of treatment sessions as the only significant predictor of satisfaction (F=10.11, p=.002, R2=.10). A larger number of sessions was associated with greater satisfaction. Even though the number of sessions was not directly related to treatment gains, it may have been indirectly related through its influence on satisfaction with treatment. However, the model could account for only 10 percent of the variance. Other possible sources of variance, not measured in this analysis, could include many variables related to the relationship of the clinician and patient and variables related to past treatment history.

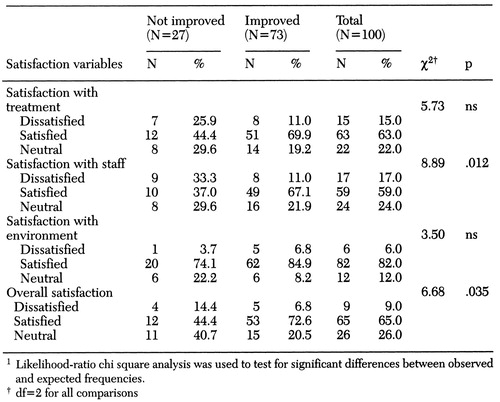

A more detailed analysis of satisfaction scores and their relationship to whether subjects had improved over the study period was done. Subjects whose total score on the Treatment Outcome Profile at follow-up was greater than the total score at intake were categorized as "improved." Scores on the overall satisfaction scale and the three satisfaction subscales were recoded into three possible responses, with responses marked 1 or 2 considered dissatisfied, those marked 3 considered neutral, and those marked 3 or 4 considered satisfied. Thus the total number and percentage of satisfied, dissatisfied, and neutral subjects in the follow-up sample were determined (see Table 2).

Overall, 65 percent of the follow-up sample reported satisfaction with services, 9 percent expressed dissatisfaction, and 26 percent were neutral. Chi square analysis revealed that overall satisfaction with services and satisfaction with staff were directly related to whether the subjects reported improvement on the Treatment Outcome Profile.

Discussion

One year after beginning treatment in an outpatient setting, patients reported reduced symptomatology and gains in quality of life and level of functioning. Those who reported the greatest gains also reported the greatest satisfaction with treatment. The strong relationship between treatment gain and satisfaction with treatment suggests that the patients themselves attribute their gains to treatment received.

It was surprising to find that variables hypothesized to have an effect on treatment gains were not shown to influence treatment. These variables included whether psychiatric medications were prescribed, clinicians' level of experience, whether the patient saw both a psychiatrist and a psychologist, patients' gender, and diagnosis. Younger patients were more likely to have greater treatment gains.

Relatively low levels of patient satisfaction with services were obtained in this sample, compared with samples of inpatients assessed at discharge (12), other samples of outpatients in mental health settings (13,14), and samples of recipients of other types of human services (15).

Several explanations for these findings are possible. The university clinic where the study was conducted was going through a stressful transition from a fee-for-service system to a capitated managed care system. Under the new system, patients were required to have a referral from their primary care physician before intake. Patients who were already in treatment were referred back to their insurance companies to clarify benefits before treatment could continue. Some of these procedures were cumbersome to the emotionally distraught persons who sought treatment.

The clinic has improved its intake procedures and has more recently adapted to managed care priorities. It is anticipated that this improved administrative effectiveness will be reflected in higher patient satisfaction ratings in the next follow-up study.

The Treatment Outcome Profile showed good sensitivity and predictive validity in revealing statistically significant gains one year after patients began treatment. Seventy-three percent of the subjects in the study reported overall improvement, with gains in quality of life, symptomatology, and level of functioning. On average, the sample gained .65 of a standard deviation from intake total scores. These one-year treatment gains serve as an internal benchmark for future comparative studies.

Likewise, the patient satisfaction ratings provide internal benchmarks for future comparisons. Subjects distinguished between their satisfaction with the environment and their satisfaction with overall treatment and treatment staff. Subjects who received more treatment sessions reported higher satisfaction. The practical meaning of patients' ratings of neutral and dissatisfied should be explored in future research. However, a high frequency of neutral and dissatisfied responses could indicate disgruntlement with administrative and financial hassles associated with receiving services in a managed care environment.

These findings are being used by administrators at the university clinic to target quality assurance efforts to improve patient satisfaction ratings and overall treatment gains. Data are also being collected from other public and private outpatient settings serving patients with different levels of functioning and different diagnoses to help establish external best-practice benchmarks using the Treatment Outcome Profile.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Debbie Dow, Gretchen Herr, Christy Lemery, Melanie Bums, and Sherry Wagner.

Dr. Holcomb, Dr. Beitman, and Dr. Hemme are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and neurology at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Mr. Josylin and Ms. Prindiville are graduate students in psychology at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Address correspondence to Dr. Holcomb at Behavioral Health Concepts, Victoria Park, 2716 Forum Boulevard, Suite 4, Columbia, Missouri 65203. William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Scores on scales and subscales of the Treatment Outcome Profile at intake and at one-year follow-up for 100 new outpatients treated at a university psychiatric clinic in 19951

|

Table 2. Satisfaction with outpatient services among patients who did and did not report overall improvement in total score on the Treatment Outcome Profile at one-year follow-up1

1. Epstein AM: The outcomes movement: will it get us where we want to go? New England Journal of Medicine 323:266-269, 1990Google Scholar

2. Flynn L, Steinwachs D: Special report: outcome round table includes stakeholders. Health Affairs 14(3):269-270, 1995Google Scholar

3. Lohr KN: Outcome measurement: concepts and questions. Inquiry 25:37-50, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

4. Andrews G: Best practices for implementing outcomes management. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 4:19-21, 1995Google Scholar

5. Thorton PH, Goldman HH, Stegner BL, et al: Assessing the costs and outcomes together: cost-effectiveness of two systems of acute psychiatric care. Evaluation and Program Planning 13:231-241, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Smith GR, Fisher EP, Nordquist CR, et al: Implementing outcome management systems in mental health settings. Psychiatric Services 48:364-368, 1997Link, Google Scholar

7. Speer DC, Newman FL: Mental health services outcome evaluation. Clinical Psychology 3:105-129, 1996Google Scholar

8. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Outcomes of inpatients treated on a VA psychiatric unit and a substance abuse treatment unit. Psychiatric Services 48:699-704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Beck AT, Steer RA: Beck Depression Inventory Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1987Google Scholar

10. Zung W: A rating scale for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12:371-379, 1971Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Norusis MJ: SPSS for Windows: Base System User's Guide, Release 6.0. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 1993Google Scholar

12. Holcomb WR, Adams NA, Ponder HM, et al: The development and construct validation of a consumer satisfaction questionnaire for psychiatric inpatients. Evaluation and Program Planning 12:189-194, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lebow JL: Client satisfaction with mental health treatment. Evaluation Review 7:729-752, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Tanner BA: Factors influencing client satisfaction with mental health services: a review of quantitative research. Evaluation and Program Planning 4:279-286, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Fornell C: A national customer satisfaction barometer, in Performance Measurement and Evaluation. Edited by Holloway J, Lewis J, Mallory G. London, Sage, 1995Google Scholar