Low Cholesterol and Violence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The association between violent behavior and low serum total cholesterol levels was examined in a psychiatric inpatient population with diverse diagnoses. METHODS: The study used a case-control design to compare the cholesterol levels of patients in a long-term psychiatric hospital who had a history of seclusion or restraints (N=20) and those who did not (N=20). A low cholesterol level was defined as less than 180 mg/dL. RESULTS: A strong association was found between low cholesterol levels and violent behavior (odds ratio=15.49), an association that was not due to age, race, sex, or diagnosis. The finding was consistent whether mean levels or dichotomized levels of cholesterol were examined. Physical health, cholesterol-lowering medication, current alcohol use, or unusual diets could not explain the results. However, the raw frequency of episodes of seclusion or restraint as an indicator of the frequency of violent behavior was not associated with cholesterol level. Dichotomizing cholesterol levels at 180 mg/dL yielded high sensitivity (90 percent) for predicting violent behavior but at the cost of low specificity (65 percent). CONCLUSIONS: The results support the hypothesis that an association exists between low cholesterol and violent behavior among psychiatric patients but argue against using cholesterol level as a screening tool for predicting violent behavior.

Trial studies of primary prevention of coronary heart disease have shown that lowering cholesterol levels reduces cardiac morbidity and mortality (1,2). However, total mortality was not reduced in these studies due to an increase in mortality from violence and suicide. This paradoxical finding has been confirmed in a meta-analysis of primary prevention trials (3). Given the public health imperatives to reduce cardiac mortality and violence, the association between lowering or lower cholesterol levels and increased mortality from violence and suicide is highly troubling and has spawned additional studies and an equal number of hypotheses to explain it (4).

The evidence for an association between low cholesterol and violence is not without its detractors, especially as the findings are equivocal in the general population and may be confounded by factors such as poor physical health and high alcohol consumption, as well as the general complexity of events surrounding violent deaths (4). The latter point was made by examining in detail the violent deaths in some of the studies mentioned above (5). Such contradictory findings have given rise to calls for more closely targeted studies examining violent behavior instead of violent deaths and specialized studies in populations vulnerable to violence (4,6).

People with mental disorders are a vulnerable group. In a study of patients with antisocial personality disorder (7) and in another study of adolescent boys with conduct disorder (8), Virkkunen also observed an association between low cholesterol and violent behavior. Of two studies conducted at the Whiting Forensic Institute (9,10), one involved 50 patients admitted to the forensic hospital for violent crimes (9). Their criminal records were rated for severity of crimes using a scale developed by the authors. The 21 subjects found to be "more violent" had lower cholesterol levels than the 29 "less violent" subjects. The second study involved 106 patients admitted for crimes of violence (10). Aggressive acts were rated and scored. The group with lower cholesterol had a higher mean frequency of aggressive incidents compared with the high-cholesterol group. These studies suggest that lower cholesterol levels are related both to the frequency of violence and to its intensity

Two recent reports have suggested that the association between low cholesterol and suicide is evident only among patients with selected disorders, most notably depression (11,12). The association was not observed among those diagnosed with schizophrenia. These findings suggest the need to examine diagnosis in studies assessing cholesterol levels and violence.

We tested the hypothesis that violent behavior is associated with low serum total cholesterol levels in a psychiatric inpatient population with diverse diagnoses. We also wanted to determine if the number of episodes of seclusion or restraint could be used as an indicator for violent behavior.

Methods

We used a case-control design to examine the association between low cholesterol and violence. All patients in the case and control groups were recruited from one public, long-term, inpatient psychiatric hospital. The hospital serves an urban catchment area; patients are transferred to the facility after an average three-week hospitalization at other facilities in the area. At the time of admission to the psychiatric hospital, fasting total serum cholesterol and triglycerides are routinely obtained.

Cases were defined as all patients who received seclusion or restraint (N=20) during a two-month period in early 1995. Control patients were defined as the first 20 patients who did not receive seclusion or restraint during the same period and who had been admitted during the same period as the patients in the case group. Names were obtained from the admissions log without reference to diagnosis or laboratory results.

Information on age, sex, race, primary psychiatric diagnosis on admission, total serum cholesterol, triglycerides, and number of episodes of seclusion or restraint within a two-month period was obtained from medical chart review. The number of incidents of seclusion or restraint was used as an indicator of violent behavior. It was truncated at 100 to facilitate data collection.

Subjects were physically healthy and were not on any lipid-lowering or -modifying drugs. No alcohol had been consumed after the initial hospitalization, and the diets for all subjects were similar. All subjects received psychotropic medications as part of their treatment.

Statistical analysis consisted of t tests and Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables and Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables. To control for potential confounders, analysis of covariance and logistic regressions were used. The analysis of covariance used total serum cholesterol as the dependent variable, whereas the logistic regression used case status as the dependent variable. Both Pearson and Spearman correlations were used to quantify the associations between level of violence and cholesterol among patients in the case group.

Results

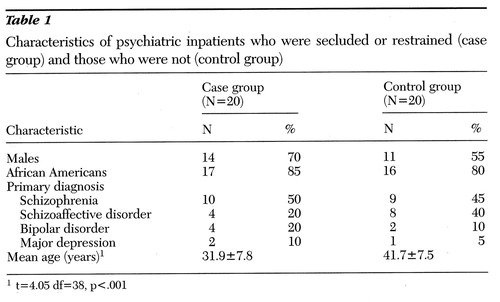

Patients in the case and control groups were similar in sex, race, and primary psychiatric diagnosis. As shown in Table 1, the majority of patients in both groups were male and African American, and most were diagnosed as having schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. However, patients in the case group were significantly younger than those in the control group

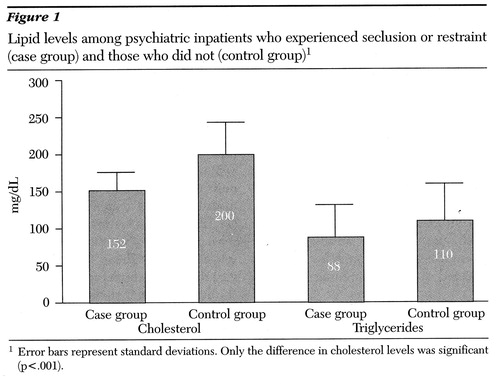

Confirming the primary hypothesis, patients in the case group had significantly lower cholesterol than those in the control group (Figure 1) (t=4.31, df=38, p<.001). No significant difference was found in triglyceride levels, but the lower mean level for the case group showed a trend toward significance (p<.16). When cholesterol levels were dichotomized at 180 mg/dL, using the recommended upper level of normality, a significantly higher proportion of the case group had lower cholesterol levels (90 percent versus 35 percent (c2= 12.9, df=1, p<.001). Using the dichotomy of 160 mg/dL yielded similar results (50 percent versus 20 percent (c2=3.96, df=1, p=.047).

The association between violence and lower cholesterol levels could be due to age differences between the two groups. Age was correlated with cholesterol level (r=.41, p=.009). To control for age, logistic regression models and an analysis of covariance were conducted. Both approaches showed an independent association between cholesterol as a continuous variable and case status (p=.003 and p=.013, respectively). From the logistic regression model, the adjusted odds ratio for the association of low cholesterol (180 mg/dL or lower) with violence was 15.49. The adjusted odds ratio for a level of 160 mg/dL was smaller (OR=4.61).

The small sample size precluded stratified analysis by diagnosis and discouraged multivariate analysis. For descriptive purposes, we compared the difference in mean total serum cholesterol levels between the case and control patients by diagnostic group. For each diagnosis, the case group had lower mean point estimates than the control group, with differences ranging from 38 mg/dL for patients with schizoaffective disorders to 76 mg/dL for patients with bipolar disorders. The reduction in mean total serum cholesterol levels from the control group to the case group ranged from 19 to 33 percent for the diagnostic groups. It should be stressed that the latter analyses did not find statistically significant differences due to lack of power, but they are presented for comparative purposes.

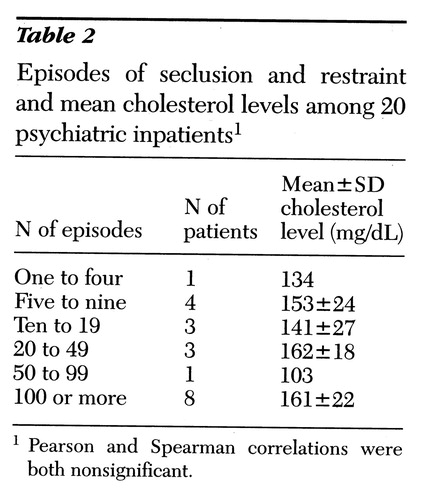

The association between the frequency of seclusion or restraint and serum cholesterol levels was explored, as Table 2 shows. No linear or rank-order association was observed.

Also explored was the utility of screening for low cholesterol as a predictor of violent behavior. Dichotomizing low cholesterol at 180 mg/dL resulted in high sensitivity (90 percent) for predicting violent behavior but at the cost of low specificity (65 percent). Changing the cutoff point to 160 mg/dL decreased sensitivity (to 50 percent) with an increase in specificity (to 80 percent). To put this finding in context, 90 percent sensitivity and 50 percent specificity were achieved using age of less than 40 years as a predictor of violent behavior.

Discussion and conclusions

In this case-control study of psychiatric patients, we observed a highly significant and strong association between lower cholesterol levels and violent behavior. Although serum total cholesterol levels were correlated with age, the primary finding was independent of age, race, sex, or diagnosis. In multivariate analysis using two different approaches, cholesterol was linked with violent behavior—not age. Moreover, the finding was consistent whether we examined mean levels or dichotomized levels of cholesterol. Physical health, cholesterol-lowering medication, current alcohol use, or unusual diets could not explain the results. As such, the findings were robust given the small sample size and the age difference. However, the raw frequency of seclusion or restraint as an indicator of the frequency of violent behavior was not correlated with cholesterol level.

The finding confirms the utility of examining the association between cholesterol level and violence in vulnerable populations, as well as the association between cholesterol level and violent behavior rather than violent death as has been advocated (4). The results extend the discussion of low cholesterol beyond suicide or mortality to violent behavior. Previous studies have examined the association among patients with a history of criminal behavior (9,10). This study extends it to the general inpatient psychiatric population. Unlike previous studies (11), comparable differences were observed in mean cholesterol level in every diagnostic group.

The robustness of the findings could inform biological models examining mechanisms of the association between low cholesterol level, aggression, and violence. Currently, one popular explanation for the association is the role of cholesterol in serotonin reuptake (13). However, this study was not designed to address the mechanism to explain the observed association.

The study was limited to information routinely obtained for medical care. As such, cholesterol levels were determined at the time of the patients' admission and not when violent behavior was observed. However, it is unlikely that cholesterol levels would change dramatically or quickly. The importance of other diseases or alcohol cannot be overlooked as confounding the association. All the subjects were physically healthy and had no current alcohol use. Their nutritional status could not be assessed directly, although previous studies had shown an association between low cholesterol and suicide, independent of nutritional status (11).

This study relied on episodes of seclusion and restraint as an indicator of violent behavior, which has the advantage of simplicity but may not capture the intensity of the violence. As a measure of frequency of violence, this indicator was not correlated with cholesterol levels. Truncating the frequency of seclusion or restraint to an upper value of 100 episodes during a two-month period limited the potential correlation that could be observed. However, no trend or even a suggestion of an association between decreasing cholesterol and increased frequency of seclusion or restraint was noted among the patients in the case group.

The utility of low cholesterol levels as a screening tool for violent behavior was limited and was comparable to using young age as a screener. The low specificity—that is, the lack of high cholesterol in the control patients—reflected the generally low cholesterol levels in the entire sample.

Our findings are limited by the small sample size and reliance on chart reviews. However, our finding of an independent association between violence and low cholesterol levels is highly statistically significant and robust to analytical methods. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to replicate the finding and enhance its generalizability to other groups. Such studies would profit by constructing a valid index of frequency or intensity of violence and examining timing and vulnerability within a specified biological model.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral neurosciences at Wayne State University School of Medicine, 2751 East Jefferson, Suite 200, Detroit, Michigan 48207.

Figure 1. Lipid levels among psychiatric inpatients who experienced seclusion or restraint (case group) and those who did not (control group)1

1Error bars represent standard deviations. Only the difference in cholesterol levels was significant (p<.001)

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who were secluded or restrained (case group) and those who were not (control group)

1t=4.05 df=38, p<.001

|

Table 2. Episodes of seclusion and restraint and mean cholesterol levels among 20 psychiatric inpatients1

1Pearson and Spearman correlations were both nonsignificant.

1. Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al: Helsinki Heart Study: primary prevention trials with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. New England Journal of Medicine 317:1237-1245, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Lipid Research Clinics Program: The lipid research clinics coronary primary prevention trials results: I. reduction in the incidence of coronary heart disease. JAMA 252:351-364, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Muldon MF, Manuck SB, Matthew KM: Lowering cholesterol concentrations and mortality: a quantitative review of primary prevention trials. British Medical Journal 301:309-314, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Santiago JM, Dalen JE: Cholesterol and violent behavior. Archives of Internal Medicine 154:1317-1321, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wysowski DK, Gross TP: Deaths due to accidents and violence in two recent trials of cholesterol-lowering drugs. Archives of Internal Medicine 150:2169-2172, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ryman A: Cholesterol, violent death, and mental disorder. British Medical Journal 309:421-422, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Virkkunen M: Serum cholesterol in antisocial personality. Neuropsychobiology 5:27- 30, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Virkkunen M, Pentinnen H: Cholesterol in aggressive conduct disorder: a preliminary study. Biological Psychiatry 19:435-439, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hillbrand M, Foster H: Serum cholesterol levels and severity of aggression. Psychological Reports 72:270, 1993 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Spitz R, Hillbrand M, Foster H: Serum cholesterol levels and severity of aggression. Psychological Reports 74:622, 1994 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kunugi H, Takei N, Aoki H, et al: Low serum cholesterol in suicide attempters. Biological Psychiatry 41:196-200, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Modai I, Valesvski A, Dror S, et al: Serum cholesterol levels and suicidal tendencies in psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:252-254, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

13. Soubrie P: Reconsidering the role of central serotonin neurons in human and animal behavior. Behavior and Brain Science 9:319- 363, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar