Stigmatizing Experiences of Parents of Children With a New Diagnosis of ADHD

Stigma associated with mental illness ( 1 , 2 , 3 ) and its treatment ( 4 , 5 , 6 ) is a well-established barrier to mental health care utilization ( 7 , 8 ). However, it is not a consistent predictor of lack of care seeking ( 5 , 9 ), poor treatment adherence ( 10 ), and early termination of treatment ( 11 ). Stigma has been conceptualized as a complex social phenomenon that includes elements of labeling, stereotyping, exclusion, loss of status, and discrimination. These elements occur together in a social situation where individuals with power allow this to occur ( 12 , 13 ).

Stigmatizing beliefs about individuals with a mental illness have created a "culture of suspicion" about mental health treatment, especially when such treatment involves a child ( 14 ). In the National Stigma Study-Children (NSS-C), Pescosolido and colleagues ( 15 ) reported that individuals believed that children who receive mental health treatment are stigmatized. The adults interviewed in the NSS-C also believed that physicians overmedicate children for common behavioral problems and that psychiatric medication has deleterious effects on the child's development and behavior ( 15 ). Furthermore, 12%–33% of NSS-C respondents believed that mental health treatment would make a child an outsider and the child would suffer as an adult ( 16 ). These negative attitudes can be a barrier to seeking help for oneself and for one's child ( 17 ).

Despite awareness of mental health stigma and the large body of evidence about the perceived stigma of child mental health treatment ( 15 , 16 , 18 ), much remains to be learned about the circumstances under which families experience stigma. The gap in our understanding of how children and their families experience stigma may be due, in part, to the relatively few qualitative studies on this topic. Rather, stigma has been primarily measured quantitatively from a hypothetical or prospective vantage point ( 13 ).

This qualitative study addressed the following research question: How do parents and their children experience mental health stigma? Fundamental to this investigation was gaining a rich description of how stigma can influence parents who are seeking mental health care for their child. In this article, the term parent is used to refer to the biological parent or primary caregiver. Implications for how such knowledge can inform best-practice approaches to implementing empirically supported treatments that are respectful of families' concerns are discussed.

Methods

Study participants

The sample was drawn from an urban area with a large proportion of low-income, African-American residents. Parents were recruited for the study if they had a child between six and 18 years who was newly diagnosed as having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). ADHD was targeted because it is a common childhood psychiatric disorder with clear evidence-based stimulant medication treatment that parents are hesitant to use ( 19 , 20 ).

Participants were recruited between November 2003 and December 2006 from primary care clinics, developmental and behavioral pediatric clinics, and specialty mental health outpatient clinics affiliated with a large teaching hospital. The clinics were purposefully targeted to capture a range of families who seek care for ADHD in an urban community. After a child's scheduled appointment, clinicians presented eligible parents with a study brochure. Interested parents met with a research team member who discussed the study protocol with them. Information on demographic characteristics, family psychiatric history, and treatments received at baseline and at six and 12 months was obtained from the child's medical chart. Written consent was obtained from those who agreed to join the study. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Of the 69 individuals approached, 48 (70%) agreed to participate and were interviewed. Recruitment across sites was as follows: 16 (33%) were from primary care clinics, 23 (48%) were from developmental and behavioral pediatric clinics, and nine (19%) were from specialty mental health clinics. The larger proportion from pediatric clinics reflects the fact that a majority of children with ADHD are cared for by pediatricians ( 21 ).

Qualitative interview procedure

For the 48 participants, interviews were conducted by telephone with 46 participants; the other two participants requested face-to-face interviews. These face-to-face interviews were scheduled either right before or right after the child's clinic appointment in a private room in the clinic. Participant confidentiality was stressed, and permission to audiotape the interview was obtained in advance. The principal investigator or a research assistant conducted all interviews. Before conducting an interview, research assistants read key articles on the epistemology and method of inquiry in qualitative research. They also conducted a practice interview that was critiqued for interviewing technique by the principal investigator and an expert consultant in qualitative methods.

All interviews were performed within one month of the child's receipt of an ADHD diagnosis. Some parents wanted to start medication treatment immediately, while others were still deciding what to do. Nonetheless, the interviews were a retrospective history of the events that led up to the child's diagnosis to identify stigmatizing experiences before the diagnosis or the decision to use medication. The strength of these data is that they capture stigmatizing experiences before treatment decisions.

The interviews were semistructured, and a field guide, developed by the principal investigator and the qualitative expert consultant, was used to elicit a discussion about parents' general understanding of their child's problems and the ADHD diagnosis, their perceptions and expectations for mental health treatment, and their perception of their own role in the child's treatment. All interviews began with the same broad but focused opening question, "How did your child end up with a diagnosis of ADHD?" Broad open-ended questions are common in qualitative research because they elicit a dialogue with the interviewee ( 22 ). In this study, participants described in their own words their personal experiences from their first awareness of their child's behaviors to the time of the initial diagnosis. The field guide included standard probes that interviewers used if the participant had not touched upon the particular issue in the discussion. Probing questions included: How did you feel about your child's problems? How did others react to your child's problems? How did you feel about medication for your child's behavior? Interviews lasted one-half hour to over one hour, and they were transcribed verbatim for analysis.

Data analysis

The analysis followed grounded theory methods to explore parents' experiences with stigma ( 23 ). Three coders used line-by-line coding to identify statements related to stigmatizing situations. Coding was an iterative process to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. Each coder read the first five interviews to establish the initial codes and definitions. Identified codes were discussed among the group, defining characteristics of each code were established, and a coding manual was developed. Next, each coder reread the first five interviews and coded the data using the revised definitions and coding manual. The coded text was again discussed among the group, and codes were refined, collapsed, or eliminated as needed. This process continued until there was 100% agreement in definitions and coded data. Coders then moved on to the next five interviews, using the definitions and coding manual established with the initial five interviews. After group discussion, if any new codes emerged in the second set of interviews, these were added to the coding manual. The coders reread the current and prior set of interviews to ensure that all information related to the existing and newly identified codes had been captured. Through this process, the coding manual evolved from the data, and 100% agreement was obtained. Saturation was reached when no new codes were identified. Data were visually displayed to look for patterns within and across participants. Fisher's exact tests were used to assess associations between stigmatizing experiences and sample characteristics.

Results

Participant description

Participants were the biological mother (N=36, 75%), biological aunt or grandmother (N=5, 10%), biological father (N=4, 8%), or stepparent (N=3, 6%) of the child. Most were single parents (N=37, 77%) and living in an urban community (N=42, 88%).

Children were mostly African American and male; they had a mean±SD age of 8.8±2.3 years. Twenty-seven (56%) had comorbid diagnoses, which included adjustment disorder (N=11, 23%), learning disorder (N=8, 17%), depression or anxiety disorder (N=7, 15%), and disruptive disorder (N=5, 10%). Nearly half (N=23, 48%) had a family psychiatric history (14 children, or 29%, with a family history of substance abuse; 11 children, or 23%, with a family history of depression). Stimulant use was noted within one month after receipt of the diagnosis for 40 children (83%).

Thematic constructs of stigma

Parents reported their perceptions of the stigmatizing experiences and beliefs in regard to their child's ADHD diagnosis and medication. Six thematic constructs emerged: concerns with labeling, feelings of social isolation and rejection, perceptions of a dismissive society, influence of negative public views, exposure to negative media, and mistrust of medical assessments. Eleven parents (23%) did not endorse any of the six thematic constructs of stigma.

Concerns with labeling. Many (N=21, 44%) did not want society to label their child as a "bad kid," a "problem child," or a "troublemaker." Some parents were concerned that, as a result of their child's misbehavior, they would be perceived as "bad parents," as not disciplining their child, or as using the behavior to get special privileges. Some parents themselves labeled their child as not a "regular kid" or "normal" like comparable age peers. Another concern was that as a consequence of being labeled, their child would be treated differently or not given the same opportunities as their peers.

Feelings of social isolation and rejection. Also common (N=19, 40%) were parents' and their child's social isolation and rejection from peers, family, and the community. All accounts of isolation and rejection were related to concerns that their child would have low self-esteem and be lonely and sad. Specific accounts were that society does not want to deal with a "child that doesn't follow directions." Parents disliked school policies that isolated their child from their peers, such as pulling children out of the classroom to get their midday dose of medication or placing the child's desk away from other children in the classroom. Parents were especially bothered by other children who were "mean" and constantly "picking" on their child. Parents also felt isolated because they were not able to talk about their child's achievements like other parents. Rather, they felt like they were the "one who has the child that has problems."

Perceptions of a dismissive society. Just over one-fifth (N=10, 21%) of parents felt that their concerns were being dismissed by primary medical professionals and school personnel. Parents asserted that living with and raising a child with ADHD provided them with some knowledge of what was best for their child. One parent noted, "I felt being a parent, you know, they're not listening to me." The perceptions of being dismissed by these individuals led parents to seek supportive services from behavioral specialists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social service agencies.

Influence of negative public views. Three parents (6%) had a close relative with strong negative opinions of medication, and thus parents were influenced by these views. For example, parents noted how these individuals would openly express their negative opinions by saying, "doctors always say something is wrong with a child and [want to] put them on medicine." This became embedded in parents' view of medication and their willingness to use it or even consider using it for their child.

Exposure to negative media. Ten parents (21%) held their own stigmatizing beliefs of the "bad things" or "horror stories" they had witnessed with stimulant treatment of children of relatives or friends or that they had seen in the media. They spoke specifically about "zombielike" effects and children looking like they were "drugged." Others associated medication treatment with substance abuse and the potential for addiction because of the medication's controlled substance designation by the Food and Drug Administration. Consequently, parents were concerned about subsequent failure in life if their child was unable to learn the material being taught in school because the child was "drugged."

Mistrust of medical assessments. Additionally, eight (17%) expressed mistrust of medical assessments. They believed the checklist items could be answered to "guarantee" their child would be placed on medication. They perceived that clinicians had no interest in trying to "work it out" before using medication. Several parents suggested that clinicians were too quick to medicate a child with ADHD; one parent said, "as soon as I took him [to the clinic] that would be the first thing they would say."

Sample characteristics associated with stigmatizing experiences

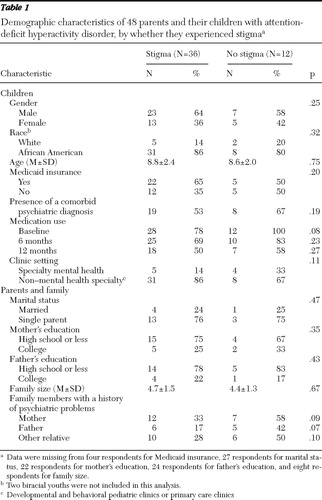

The demographic characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 1 . Because the parents could have expressed more than one type of stigma (for example, labeling and mistrust), the data were condensed to those who did and did not express stigma. There were no significant differences between the groups. However, compared with participants who did not experience stigma, those who experienced stigma were less likely to have a child who was using medication at baseline (p=.08) and less likely to have a father (p=.07) or a mother (p=.09) with a history of psychiatric problems, although these findings were not statistically significant. There were no differences in whether participants experienced stigma based on where the ADHD was being treated (mental health clinics versus non-mental health specialty clinics). However, in comparing the individual categories of stigma, parents were more likely to express labeling stigma if they were recruited from non-mental health specialty clinics (that is, developmental and behavioral pediatric clinics or primary care clinics) (N=21 of 39, 54%), compared with those recruited from specialty mental health clinics (N=0 of 9, 0%) (p<.01).

|

Discussion

Stigma around children's mental illness and treatment is a complex issue and is experienced differently across families, even in this fairly homogeneous sample. In this study stigmatizing experiences were rooted in views of medication for childhood behavior. Although attitudes toward mental health treatment have improved ( 17 , 24 ), McLeod and colleagues ( 25 ) found that the public is not well informed about ADHD and that people are more likely to prefer counseling over medication for the treatment of ADHD. This may be especially true for families in primary care settings, who may be more naïve to mental health care and more sensitive to labeling issues than families seen in mental health specialty settings.

Recent evidence suggests an inverse relationship between stigma experiences and psychiatric medication use ( 26 ). One could hypothesize that negative public views and exposure to negative media lead to mistrust of assessments and consequently to avoidance of medication. A separate analysis of these data by the primary author found that views of medication as acceptable (versus unacceptable) were associated with medication treatment adherence ( 27 ). Parents viewing medication as unacceptable were more likely to express stigmatizing experiences (p<.01).

This study illustrates how families of children newly diagnosed with ADHD experienced stigma. Many parents felt that they and their child were isolated as a result of their child's behavior. Preferences for social distance from those with a mental illness have been noted in the literature ( 28 ). For example, children with depression are also thought to have a greater potential for violence ( 16 , 29 ), and these beliefs lead to discriminating behaviors, such as avoidance and segregation of the stigmatized person ( 30 ). However, isolation can also stem from parents' guilt and blame for their child's illness ( 31 ). In the study presented here, parents were concerned about the subsequent effect on their child's self-esteem and future well-being. The next step is to investigate the mechanisms by which high levels of internal distress, loneliness, sadness, and low self-esteem stemming from isolation and segregation affect mental health outcomes.

Most parents in this sample (N=37, 77%) mentioned a stigmatizing experience related to their child's behavior well before they sought care for ADHD. Earlier research has suggested that negative perceptions of mental illness are in place before one seeks treatment ( 1 ). However, there may be a number of other ways in which stigma may affect parents' decisions to seek treatment for their child. Parents' perception and understanding of the problem and their individual preferences for treatment are likely to be critical factors that shape views of stigma. Investigating ways to overcome stigma in order to optimize use of mental health treatments is an important area for future research ( 32 ).

The findings offer several implications for public policy and practice, and they highlight the necessity of multiple perspectives for community outreach and public health programs aimed at reducing mental health stigma among families and children. The public health approach has traditionally been through public health education, but this has yielded small effects ( 33 ). The hope is that increased awareness of mental health stigma minimizes the shame and guilt associated with the mental illness, facilitates the identification of others who are mentally ill, and encourages the public to challenge mental health stigma directly ( 33 ). From the school system perspective, policies, procedures, and interpersonal communication around mental health issues need to be developed and enhanced in light of the potential for isolation of the child and his or her family. Moreover, from the medical community perspective, providers need to consider how clinical evaluation and treatment may be stigmatizing for some families, especially in pediatric primary care settings.

The study should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, the sample reflects only individuals who were seeking care for their child; parents who have not yet sought health care for their child may have different experiences than those expressed in the study. Second, the primarily urban, low-income sample limits the possibility that the findings would generalize to other populations. Nonetheless, this is a population that is vulnerable to mental health stigma. Third, the mistrust of medical assessments was likely lower than what might be expected in the general population because some parents did not know enough about ADHD to question the process. In addition, the negative influence from relatives also may be underestimated because many of the female caregivers (mothers and aunts) were single, and these respondents may either have been isolated from extended relatives or had a smaller support network. The work by Bussing and colleagues ( 34 ) has shown that parents with less "instrumental network support" are more likely to use medication. Finally, because the vast majority of our sample was composed of female caregivers, it may not represent views of male counterparts. An important area for future research is to explore whether the stigmatizing experiences represented in this study are unique to this sample or similarly shared among families of other socioeconomic, geographic, racial, and ethnic origins.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that most parents experienced some aspect of stigma related to their child's ADHD and medication, many used medication for their child's ADHD. Perceived benefits may have outweighed stigmatizing barriers. Future research should examine how parents balance perceived benefits of treatment with mental health stigma concerns. This would shed light on mechanisms underlying how stigmatizing views influence access and adherence to children's mental health treatment. Such knowledge will lead to better approaches to overcome and eliminate stigma as a barrier to mental health services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant MH-65306 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, et al: A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54:400–423, 1989Google Scholar

2. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328–1333, 1999Google Scholar

3. Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:188–207, 2000Google Scholar

4. Cooper AE, Corrigan PW, Watson AC: Mental illness stigma and care seeking. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 191:339–341, 2003Google Scholar

5. Vogel DL, Wade NG, Hackler AH: Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: the mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology 54:40–50, 2007Google Scholar

6. Vogel DL, Wade NG, Haake S: Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. Journal of Counseling Psychology 53:325–337, 2006Google Scholar

7. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

8. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

9. Corrigan PW, Miller FE: Shame, blame, and contamination: a review of the impact of mental illness stigma on family members. Journal of Mental Health 13:537–548, 2004Google Scholar

10. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Stigma as a barrier to recovery: perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatric Services 52:1615–1620, 2001Google Scholar

11. Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, et al: Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:479–481, 2001Google Scholar

12. Link BG, Phelan JC: Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27:363–385, 2001Google Scholar

13. Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, et al: Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:511–541, 2004Google Scholar

14. National Advisory Mental Health Council, Workgroup on Child and Adolescent Mental Health Intervention Development and Deployment: Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, Office of Communications and Public Liaison, 2001Google Scholar

15. Pescosolido BA, Perry BL, Martin JK, et al: Stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs about treatment and psychiatric medications for children with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58:613–618, 2007Google Scholar

16. Pescosolido BA, Fettes DL, Martin JK, et al: Perceived dangerousness of children with mental health problems and support for coerced treatment. Psychiatric Services 58:619–625, 2007Google Scholar

17. Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC: Stigma and its impact on help-seeking for mental disorders: what do we know? Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 17:31–37, 2008Google Scholar

18. Pescosolido BA: Culture, children, and mental health treatment: special section on the National Stigma Study-Children. Psychiatric Services 58:611–612, 2007Google Scholar

19. DosReis S, Butz A, Lipkin P, et al: Attitudes about stimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among African-American families in an inner city community. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 33:423–430, 2006Google Scholar

20. dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al: Parental perceptions and satisfaction with stimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 24:155–162, 2003Google Scholar

21. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al: Psychotherapeutic medication patterns for youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 153:1257–1263, 1999Google Scholar

22. Spradley JP: The Ethnographic Interview. New York, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1979Google Scholar

23. Glaser BG: The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems 12:436–445, 1965Google Scholar

24. Mojtabai R: Americans' attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services 58:642–651, 2007Google Scholar

25. McLeod JD, Fettes DL, Jensen PS, et al: Public knowledge, beliefs, and treatment preferences concerning attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Services 58:626-631, 2007Google Scholar

26. Kanter JW, Rusch LC, Brondino MJ: Depression self-stigma: a new measure and preliminary findings. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 196:663–670, 2008Google Scholar

27. dosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, et al: The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents' initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 19:377–383, 2009Google Scholar

28. Martin JK, Pescosolido BA, Olafsdottir S, et al: The construction of fear: Americans' preferences for social distance from children and adolescents with mental health problems. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 48:50–67, 2007Google Scholar

29. Perry BL, Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, et al: Comparison of public attributions, attitudes, and stigma in regard to depression among children and adults. Psychiatric Services 58:632–635, 2007Google Scholar

30. Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Otey E, et al: How do children stigmatize people with mental illness? Journal of Applied Social Psychology 37:1405–1417, 2007Google Scholar

31. Hinshaw SP: The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46:714–734, 2005Google Scholar

32. Charach A, Volpe T, Boydell KM, et al: A theoretical approach to medication adherence for children and youth with psychiatric disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 16:126–135, 2008Google Scholar

33. Corrigan PW, Wassel A: Understanding and influencing the stigma of mental illness. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 46:42–48, 2008Google Scholar

34. Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, et al: Social networks, caregiver strain, and utilization of mental health services among elementary school students at high risk for ADHD. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42:842–850, 2003Google Scholar