The Effect of Services and Stigma on Quality of Life for Persons With Serious Mental Illnesses

Since the development of labeling theory, scholars have debated the effects of psychiatric labels on the lives of individuals diagnosed as having serious and persistent mental illness. Although early theorists argued that labels are stigmatizing and likely to create careers in mental illness ( 1 ), critics of the labeling perspective have maintained that labels have little, if any, lasting effects ( 2 , 3 , 4 ) and that the benefits of receiving mental health services outweigh any potential experiences of stigma ( 4 , 5 ).

More recent models of labeling theory focus on the social and psychological consequences of labels, including perceived discrimination, negative self-concept, and poor quality of life ( 6 , 7 ). Although this approach is more nuanced than earlier theories, the question of the relative effects of services and stigma on the lives of persons with serious mental illness remains largely unexamined. We know of only one study that directly examined the simultaneous influence of these two factors on quality of life ( 8 ). This study revealed that services, particularly those that provide economic resources and are empowering, are positively related to the quality of life of individuals with chronic mental illnesses. The study also showed that stigma is negatively associated with quality of life. These findings underscore the importance of self-concept in the relationship between services, stigma, and quality of life; however, they were based on cross-sectional data and therefore do not provide information about changes in quality of life as a function of changes in self-concept.

Self-concept plays an important role in linking services and stigma to quality-of-life outcomes. In the study discussed above ( 8 ), as well as in more recent work ( 9 , 10 ), researchers have shown that self-esteem and mastery mediated the relationship between services received and quality of life. Additionally, a key assumption of the modified labeling theory is that stigma associated with psychiatric labels has erosive and potentially long-term effects on a person's self-concept ( 6 , 7 ), a relationship that has been demonstrated empirically in numerous studies ( 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). In sum, a positive self-image has implications for quality of life that can be both enhanced by services and reduced by perceived stigma.

Mental health professionals and researchers have emphasized the importance of linking services to improved quality of life among individuals with serious and persistent mental illnesses ( 10 ). At the same time, stigma is related to a decline in well-being and life satisfaction in this population ( 8 , 12 , 15 ). For this reason, it is important to pursue research that examines the effects of both services and stigma on self-concept and quality of life.

The purpose of this study was to extend previous work by using two waves of data to explore changes in quality of life as a function of services, stigma, and self-concept; investigate the role of self-concept in the relationship between services, stigma, and quality of life; and examine changes in self-concept as a function of services and stigma.

Methods

Sample

The data used here were part of a larger study designed to investigate the relationships between stigma, psychiatric services, and well-being for consumers of community mental health services ( 16 ). We collected "permission to contact" forms from 796 individuals in various sites (described below), and we were able to successfully contact and interview 370 (46%) at time 1. At time 2 (approximately six months after baseline) we interviewed 262 (71%) of the time 1 respondents.

The final sample for the analyses presented here comprised 188 (72%) of the 262 individuals who met the following criteria: they were clients of a single public mental health agency that exclusively serves adults with serious and persistent mental illnesses; we had access to their clinical records for the purpose of obtaining information about their principal diagnosis and potential co-occurring substance use disorders; and they reported using case management services during the study period. This subsample consists of 35 individuals recruited from an outpatient mental health center, 62 individuals from a free-standing psychiatric crisis center, and 91 individuals from mental health court. Institutional review boards of all involved agencies and universities approved the study.

Case managers, treatment team members, or members of the research team initially contacted respondents. Respondents were at least 18 years old and had been a resident of the county for one year or longer. Interviews were scheduled at one of the treatment facilities, and respondents received $20 and $25 at the first and second interview, respectively. Baseline interviews were conducted between 2002 and 2005, and follow-up interviews were conducted between 2003 and 2006. The range of time between interviews was four to 12 months, with a mean±SD of 6.39±1.63.

Although our sample was not a random sample of individuals with serious and persistent mental disorders, it offered an advantage because it included individuals from multiple recruitment sites who were accessing a wide range of services, thereby providing an opportunity to examine these processes with a broader sample than in previous research.

Measures

Quality of life. Quality of life was measured by using an item from Lehman's inventory ( 17 ) asked at two points during the interview. Respondents were asked how they felt about their lives in general. Responses ranged from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted. Scores on the two questions were summed to create one measure of life satisfaction. The correlation for these two items was .614 at time 2 (.720 at time 1).

Services. At time 2, respondents were asked about services received in the past six months. In preliminary analysis we considered the effect of 12 categories of services. [A table showing the frequencies of the 26 specific services in these categories is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] The results of exploratory analysis indicated that among these services, inpatient treatment and counseling services were significantly related to changes in quality of life, our measures of self-concept, or both. Therefore, we focused on these two services. Inpatient services included psychiatric hospitalizations in a state hospital, psychiatric hospitalizations in a general hospital, crisis stabilization, and respite services. Counseling services included individual counseling, group counseling, and family counseling. Each index was composed of the count of specific services within the category, with a range of 0 to 3 for counseling and 0 to 4 for inpatient services.

Stigma. Our measure of stigma was adapted from Link's Devaluation-Discrimination scale ( 6 ), a widely used scale considered to have excellent psychometric properties ( 18 ). This 12-item scale assessed respondents' beliefs about how others react to individuals with mental illnesses. Respondents were asked the extent to which they agreed with statements such as, "most people in my community would treat a former mental patient just as they would treat anyone," "most people believe that a former mental patient is just as trustworthy as the average citizen," and "most people feel that having a mental illness is a sign of personal failure." Positively worded items were reverse coded, and all items were summed to create a scale ranging from 12 to 72. Higher scores indicated higher levels of perceived stigma. Internal consistency was excellent, with alpha values of .87 at times 1 and 2.

Self-concept. Consistent with previous research, our study focused on two aspects of self-concept: self-esteem and mastery. Self-esteem was measured with Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale ( 19 ), which asks individuals the extent to which they agree with the following statements: "I take a positive attitude toward myself"; "on the whole, I am satisfied with myself"; and "I wish I could have more respect for myself." Negatively worded items were recoded and all items were summed to create a scale that ranged from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. Internal consistency was excellent, with alpha values of .91 at both baseline and follow-up.

Mastery was measured with the seven-item scale developed by Pearlin and colleagues ( 20 ). Respondents were asked whether they agreed with the following statements: "I have little control over the things that happen to me," "there is little I can do to change many of the important things in my life," and "what happens to me in the future mostly depends on me." Possible scores range from 7 to 42, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mastery. Internal consistency was very good, with alpha values of .74 at both interviews. Both measures of self-concept are widely used and have been found to have high validity and reliability ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ).

Control variables

We controlled for baseline measures of quality of life, self-esteem, and mastery. We also controlled for depressive symptoms, psychiatric diagnosis, and co-occurring substance use disorders in order to address selection into services and potential spurious associations between our study variables that might be due to symptoms and functioning.

Initial analyses revealed that gender, age, ethnicity, education, and employment status were not related to quality of life. Additionally, recruitment site did not change the magnitude or pattern of significant findings. In order to preserve degrees of freedom in this somewhat small sample, these variables are not included in the models presented here.

We used ordinary least-squares regression analyses to examine the effects of services and stigma on changes in quality of life, the effects of self-esteem and mastery on changes in quality of life, and the influence of services and stigma on changes in self-concept over time. This last set of analyses allowed us to examine whether self-esteem and mastery are directly affected by received services and perceived stigma. In each analysis, change was measured by examining time 2 outcomes, controlling for time 1 levels of those variables.

Given the correlations between self-concept measures (r=.704), we examined both the independent and combined effects of self-esteem and mastery. We also conducted analyses to assess multicollinearity in each model. The results of these analyses (not shown) indicated that the variance inflation factor and tolerance scores were well within range, indicating that collinearity was not an issue.

Results

As indicated in Table 1 , 38% of the 188 participants were female, and 22% were employed. Ninety (48%) were white, 84 (45%) were black, and 14 (8%) were from another race or ethnicity. The mean number of years of education was 11.87±2.07, and the mean age of the sample was 40.61±9.88. Also presented in Table 1 is information on the distribution of psychiatric diagnoses. As shown, the most common principal diagnosis was schizophrenic spectrum disorder (57%), with depressive disorder (16%) and bipolar disorder (16%) making up the majority of the remainder of the sample.

|

Table 1 also shows the mean scores for the key study variables. As evidenced in this table, the mean scores for self-concept remained relatively stable between baseline and follow-up (correlations over time range from .593 for mastery to .738 for self-esteem). Quality of life was the only variable that had a statistically different mean between times 1 and 2, with a higher mean at follow-up.

Effects of services, stigma, and self-concept on quality of life

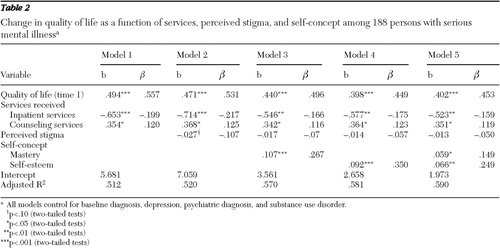

Table 2 presents the results of the regression analysis examining the relationships between quality of life, services, stigma, and self-concept. As shown in model 1 of Table 2 , inpatient and counseling services were both significantly associated with changes in quality of life. Specifically, inpatient services were associated with decreases in quality of life ( β =–.199, p<.001), and the use of counseling services was associated with an increase in quality of life ( β =.120, p=.025). Model 2 also shows that the negative relationship between perceived stigma and change in quality of life approached but did not reach significance at the .05 level. Moreover, the inclusion of stigma did not affect the relationship between services and quality of life.

|

In models 3 and 4 we included measures of self-concept. Consistent with previous research ( 8 , 10 ), mastery was positively associated with changes in quality of life ( β =.267, p<.001), as was self-esteem ( β =.350, p<.001). Both effects remained statistically significant when each measure was included in the same equation ( β =.149, p=.029 for mastery and β =.249, p=.002 for self-esteem). Although the effects of inpatient services and counseling services diminished with the addition of these variables, both services remained significantly related to changes in quality of life.

Effects of services and perceived stigma on self-concept

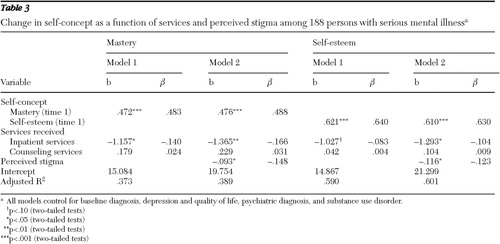

Table 3 shows the influence of services and perceived stigma on changes in self-concept. Model 1 shows that inpatient services were negatively associated with changes in mastery ( β =–.140, p=.020) but not with changes in self-esteem. Surprisingly, counseling services were not associated with changes in either mastery or self-esteem between time 1 and 2.

|

Model 2 shows that perceived stigma also had an impact on changes in these personal resources. Perceptions of stigma decreased mastery ( β =–.148, p=.019) and self-esteem ( β =–.123, p=.016). Additional analyses (not shown) confirmed that the effects of stigma on changes in self-concept remained essentially the same with or without services in the model. Thus, consistent with previous research based on cross-sectional data ( 8 ), services and perceptions of stigma appeared to have independent effects on self-concept.

Discussion

In this study we examined the relationships between mental health services, perceived stigma, self-concept, and quality of life among persons with serious and persistent mental illnesses. Our first goal was to assess the effects of services and stigma on changes in quality of life. We found that services have both positive and negative effects on changes in quality of life. In particular, although counseling services were associated with increased life satisfaction, the opposite was true for inpatient services. We also found that although the effect of stigma on quality of life approached significance, stigma was not significantly associated with a decrease in quality of life over the study period. It should be noted that consistent with previous research ( 8 ), when baseline measures were not included in the models, stigma was negatively associated with quality of life.

A second goal of this study was to assess the role of self-concept in the relationship between services, stigma, and quality of life. In general, we found that although mastery and self-esteem slightly reduced the relationship between services and changes in quality of life, these aspects of self-concept reduced the relationship between stigma and quality of life by 60%.

Our final goal was to assess the effects of services and perceived stigma on changes in self-concept. Of the 12 types of services considered, only inpatient services had an effect (negative) on self-concept. We also found that perceived stigma had a negative impact over time on self-esteem and sense of control.

Overall, and consistent with previous studies ( 8 ), our findings suggest that services and stigma operate independently of one another. The effects of services on self-concept and quality of life were not affected by stigma, and the effects of stigma on self-concept were not affected by services.

Although this study provides insight into these relationships, there are many directions future research could take. We believe that the first step should be to clarify the relationships between types of services and their impact on particular aspects of self-concept. We found that all services did not affect self-concept and quality of life in the same way. Previous work in this area has focused on specific types of services, mainly those that promote recovery or empowerment ( 8 ). However, these services are not available to a large portion of the population with mental illness. Moreover, depending on an individual's stage in the recovery process, different types of services (for example, payeeship and housing assistance versus vocational training and counseling) may be more beneficial. This may be especially true with respect to the influence that services have on aspects of the self.

The two waves of data allowed us to examine changes in self-concept and quality of life as a result of services and stigma, which advances work in this area. However, it is possible that some of the services we examined showed null or negative effects in the short term but would have potentially positive consequences in the long term. Conversely, the effect of stigma on quality of life might have been more pronounced had we assessed it more frequently and for a longer period of time. Exploring these questions will require several waves of longitudinal data.

Another important direction for this research is to examine the effects of services on changes in perceptions of stigma. In this study we focused on changes in both quality of life and aspects of self as outcome measures. It is likely, however, that services have an influence on whether individuals experience or perceive stigma in their daily lives. Identifying what types of services are beneficial or harmful with respect to cultivating or perpetuating stigma will be an important aspect of this research.

Future research should also consider additional measures of service utilization. In our sample presumably all patients had an assigned case manager, but only 85% reported use of case management services during the period between interviews. On the other hand, more than half of the sample (53%) reported receiving individual counseling during the study period, despite the relatively sparse resources for formal counseling at the treatment agency involved in this study. This relatively high rate of reported counseling services may be a reflection of individuals' reporting both formal and informal forms of counseling. Although there is no reason to believe that perceptions of use are not important and valid measures of services received, future studies might consider supplementing self-reports with more objective measures of services. These measures (from some objective source, such as billing records) could also assess the extensiveness and intensiveness of the services received.

Conclusions

This study contributes to a growing body of literature linking services, stigma, and quality of life among individuals with serious and persistent psychiatric disorders. Although mental health scholars have advanced our understanding of the connections between stigma and self-concept, studies examining this important issue should continue to develop a theoretical framework within which to examine these processes in the context of treatment. Moreover, and as suggested in previous research ( 10 ), clinicians should consider stigma reduction as an additional goal of treatment, because stigma may impede recovery by eroding personal resources.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank the research team members based at Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine, the University of Akron, and Kent State University, in particular Jennifer L. S. Teller, Ph.D., for their assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. Data collection was supported by grant 02.1176 from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and grant 2002-DG-C01-7068 from the Office of Criminal Justice Services.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Scheff TJ: The labeling theory of mental illness. American Sociological Review 39:444–452, 1974Google Scholar

2. Gove WR: Labeling of Deviance: Evaluating a Perspective. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1980Google Scholar

3. Gove WR, Fain T: The stigma of mental hospitalization: an attempt to evaluate its consequences. Archives of General Psychiatry 28:494–500, 1973Google Scholar

4. Gove WR: The career of the mentally ill: an integration of psychiatric, labeling/social construction, and lay perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 45:357–375, 2004Google Scholar

5. Spitzer RL: On pseudoscience in science, logic in remission, and psychiatric diagnosis: a critique on Rosenhan's "On Being Sane in Insane Places." Journal of Abnormal Psychology 84:442–452, 1975Google Scholar

6. Link BG: Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review 52:96–112, 1987Google Scholar

7. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, et al: A modified labeling theory approach to mental illness: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54:100–123, 1989Google Scholar

8. Rosenfield S: Labeling mental illness: the effects of received services and perceived stigma on life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 62:660–672, 1997Google Scholar

9. Corring DJ, Cook J: Use of qualitative methods to explore the quality-of-life construct from a consumer perspective. Psychiatric Services 58:240–244, 2007Google Scholar

10. Vauth R, Kliem B, Wirtz M, et al: Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 150:71–80, 2007Google Scholar

11. Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, et al: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:1621–1626, 2001Google Scholar

12. Markowitz FE: The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 39:335–347, 1998Google Scholar

13. Wright E, Gronfein, WP, Owens TJ: Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41:68–90, 2000Google Scholar

14. Markowitz FE: Modeling processes in recovery from mental illness: relationships between symptoms, life satisfaction, and self-concept. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 42:64–79, 2001Google Scholar

15. Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al: On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnosis for mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 38:177–190, 1997Google Scholar

16. Ritter C, Munetz MR, Teller JLS, et al: The quality of life of people with mental illness: effects of participation in Akron's mental health court on consumers' quality of life, New Research in Mental Health 17:124–135, 2007Google Scholar

17. Lehman AF: Instruments for measuring quality of life in mental illness; in Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. Edited by Katschnig HFH, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

18. Ritsher JB, Phelan JC: Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research 129:257–265, 2004Google Scholar

19. Rosenberg M: Society and Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1965Google Scholar

20. Pearlin LI, Lieberman MA, Menaghan EG, et al: the stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 22:337–356, 1981Google Scholar

21. Hagborg WJ: The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and Harter's Self-Perception Profile for adolescents: a concurrent validity study. Psychology in the Schools 30:132–136, 1993Google Scholar

22. Seeman M: Alienation and anomie; in Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes. Edited by Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS. San Diego, Academic Press, 1991Google Scholar