Pregnancy-Related Discontinuation of Antidepressants and Depression Care Visits Among Medicaid Recipients

Women in their reproductive period (age 15–45) face twice the risk of major depression as similarly aged men ( 1 , 2 ). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum is of particular concern because it is associated with poorer maternal and infant outcomes, including preterm birth and low birth weight ( 3 , 4 ). Maternal depression is also associated with risk of mental disorders among children ( 5 , 6 , 7 ), which can be mitigated by effective treatment of depression for mothers ( 8 ). Pregnancy may place women with preexisting depression and established treatment at particular risk; the rate of depression relapse among women is as high as 43% ( 9 ).

Treatments for major depressive disorder reach only a small subset of depressed women, with vulnerable populations such as those with low income at highest risk of inadequate care ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). Pregnancy presents additional potential barriers to the delivery of depression care. Although antidepressant medications have established efficacy, with improved mental health outcomes for women and their infants, concerns among both patients and health care providers about possible teratogenic effects may lead to discontinuation of antidepressant use in pregnancy ( 15 ). Although the absolute risk of such effects is quite low ( 16 ), in utero exposure to antidepressants is associated with transient agitation ( 16 , 17 , 18 ) and, for some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, fetal cardiac anomalies ( 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 ). Antidepressants are also found in breast milk, creating concern for women who breastfeed after delivery ( 23 ). However, psychotherapy is also effective in treating maternal depression and provides an appropriate alternative to antidepressant medications for patients and health care providers wishing to avoid medications ( 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ). A recent report by the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology represents an important first consensus statement on approaches to the treatment of depression in pregnancy ( 28 ).

Although pregnancy increases women's interaction with the health care system, relationships with existing health care providers are often disrupted during pregnancy and postpartum, which complicates depression care. This discontinuity of care may be exacerbated by a lack of coordination between care providers ( 29 ). Despite recommendations to identify psychological disorders in preconception visits, develop plans for the management of depression in pregnancy, and coordinate depression care between mental health, primary care, and maternal care providers, such actions are infrequent ( 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ). Even when depression is detected, many maternal care providers are uncomfortable treating depression without input from mental health care providers ( 33 , 34 , 35 ).

Disparities in the quality of depression services may create particular difficulties for the delivery of depression care to economically disadvantaged women during pregnancy ( 12 , 13 ). Although women insured by private health maintenance organizations (HMOs) may have minimal discontinuation of depression treatment during pregnancy and postpartum, it is less clear how pregnancy affects continuation of depression care among low-income women ( 36 ). In the only study we are aware of that has addressed this question, 60% of women receiving mental health care during pregnancy did not receive care in the six months after delivery ( 37 ). However, the study was limited to a small geographic location, had a relatively small sample of women receiving care during pregnancy (N=248), provided no information about care received before pregnancy, and did not include a nonpregnant comparison group.

On the basis of these considerations, we used Medicaid claims data to create a national cohort of low-income pregnant women who were being treated for depression. We assessed the degree to which engagement in the maternal care system was associated with discontinuation of treatment for major depressive disorder (use of antidepressants or visits for depression care) relative to a comparison group of women who were receiving routine gynecological care. Our method allowed us to ascertain rates of depression care from the prepregnancy period through the postpartum period. We hypothesized that rates of treatment discontinuation would be greater among women entering maternal care and that these discrepancies would persist into the postpartum period. In addition, we explored whether demographic characteristics would modify treatment utilization.

Methods

A study cohort of 3,237 women aged 15–45 years from all 50 states who gave birth from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2000, was identified from Medicaid claims data. Patient-level information from 1999 and 2000 statewide Medicaid MAX files that include the Personal Summary File, Other Therapy, Inpatient, Long-Term Care, and Prescription Drug files were used to identify participants. A matched cohort that provided time-yoked dyadic partners to those in pregnancy care over the course of the pregnancy was created; the women in this control group were receiving routine gynecologic care. The creation of these groups allowed comparison of depression care utilization and antidepressant treatment in the prepregnancy period (120 days before the first prenatal visit), pregnancy (0–270 days from first prenatal visit to birth), and in the postpartum period (180 days postdelivery), with comparable care periods created for the nonpregnant matched control group. The index date for these periods was based on the first prenatal visit for pregnant women and the date of a routine gynecologic visit for nonpregnant women.

The study and control cohorts were created by first selecting the index date for the study group by identifying any prenatal visit ( ICD-9 codes V22 or V23) occurring in the five-month period from May 1, 1999, to October 1, 1999. Next, an index date was created from the remaining pool of potential participants for those who had a routine gynecologic visit ( ICD-9 code V72.3) in the same period.

Participants were selected who had an outpatient visit in which depression ( ICD-9 code 296.2, 296.3, 298.0, 300.4, 309.1, or 311) was coded as a primary or secondary diagnosis in the 120 days immediately before the index date. Members of the study group were further selected according to presence of a birth code ( ICD-9 codes 650, V30–37, V50, V270, V272, V273, and V275–276) after the index date. Participants from both groups were excluded if they had a birth code 120 days before or more than 330 days after the index date. The study and control groups were then limited to those aged 15–45 with continuous Medicaid enrollment from 120 days before to 330 days after the index date. Finally, the study participants were matched at a 1:1 ratio with participants from the control group on the basis of race (white or nonwhite), age ±3 years, state of residence, receipt of cash assistance as part of welfare benefit, depression diagnosis 120 days before the index date, and presence of an antidepressant claim (as determined by 2001 National Drug Code) in the 120 days before the index date. To have a period comparable with the prenatal period for the control participants, a "pseudo-birth date" was assigned to the women in the control group so that the period from index to birth (and pseudo-birth) were identical. Basic demographic characteristics (age, race, and county) were identified from the Medicaid personal summary data. Race was based on participant self-identification and dichotomized to white and nonwhite because the small proportions of study participants who identified as specific nonwhite races precluded meaningful analysis. Race was included as a study variable because of well-established disparities in depression care utilization associated with race ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ).

Statistical analyses used Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel chi square tests to account for the matched sample. Conditional logistic regressions were used to assess whether an interaction effect was present between pregnancy status and each demographic variable. Institutional review board approval for this study was granted by the University of Pennsylvania. Individual written consent was not obtained because the analyses used administrative billing data. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed, and personal identifiers were protected from disclosure.

Results

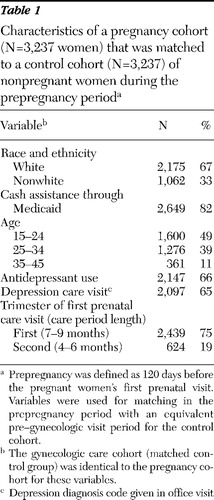

Table 1 shows characteristics of the study sample and includes the variables used to match the pregnancy and routine gynecologic care cohorts. The study sample comprised 6,474 women (3,237 women in each cohort). The women were of low income (all were enrolled in Medicaid, and 82% were receiving cash assistance from the program), and relatively young; most women were white. Three-quarters of the pregnant women initiated prenatal care in the first trimester, and only 6% initiated care in the third trimester. Antidepressant medication was used in the 120 days before the index date (first prenatal visit or gynecologic visit) by most participants (66%), and a similar portion had an outpatient visit in which a depression diagnosis was coded (65% received depression care).

|

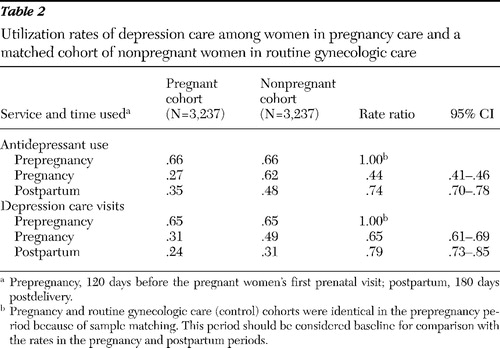

Table 2 illustrates the rates of antidepressant use and depression care visits and the rate ratios for care utilization for both cohorts during the prepregnancy, pregnancy, and postpartum periods. During pregnancy, rates of antidepressant use and depression care visits were reduced by more than 50%, to .27 and .31, respectively. Both antidepressant use and depression care were significantly decreased in the pregnancy cohort relative to the control group during both pregnancy and the postpartum periods (all comparisons p<.05).

|

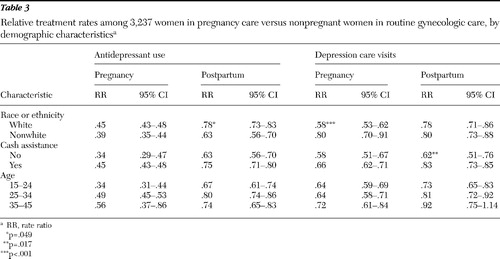

Table 3 illustrates the relative rates (rate ratios) of utilization of antidepressant use and depression care visits in pregnancy and control cohorts stratified by race and ethnicity, receipt of cash assistance, and age. Race interacted with pregnancy status such that pregnant white women had a greater reduction in depression care visits during the pregnancy period than pregnant nonwhite women relative to the control group. For antidepressant use during the postpartum period, pregnant nonwhite women had significantly greater reduction in antidepressant use than pregnant white women relative to the control group. Receipt of cash assistance also interacted with pregnancy status during the postpartum period, such that pregnant women not receiving assistance had significantly fewer depression care visits than women receiving assistance relative to those in the control group. No other interactions were identified.

|

Discussion

In this study of nearly 6,500 Medicaid recipients with established care for depression, we found that women who become pregnant significantly reduced their ongoing depression care compared with the control group of nonpregnant women. Although utilization of depression care diminished over time for both groups, the pregnant women had a significantly greater drop in antidepressant prescription claims and outpatient visits. This drop persisted in the postpartum period, when concerns related to fetal exposure to medications were no longer relevant. Moreover, there were additional effects of pregnancy status on depression care utilization across demographic variables. The relative reduction in antidepressant use postpartum was significantly less for white women than nonwhite women, whereas the relative reduction in outpatient visits was greater for white women than nonwhite women during pregnancy. The relative reduction in visits was also greater for those without cash assistance in the postpartum period. These findings indicate that pregnancy creates obstacles to ongoing depression care among low-income women receiving Medicaid benefits. Further investigation is needed to determine whether the obstacles to care that produced this drop lie in the care delivery system (for example, from poor coordination of care or concerns of prenatal providers) or perhaps with the women themselves who may have beliefs that complicate the treatment of depression in pregnancy and postpartum.

The results of this study are consistent with previous work that documented decreased depression care during pregnancy among a sample of women receiving Medicaid benefits but was limited to a small geographic location and a small sample and did not include a comparison group to control for the natural drop-off in care for depression over time ( 37 ). In contrast a study of privately insured women in a regional HMO found that although antidepressant use decreased during pregnancy (although much less than we observed in this study), utilization returned and even exceeded prepregnancy levels after pregnancy ( 36 ). In that study there was no drop in mental health visits in pregnancy compared with prepregnancy, counter to what we found in this Medicaid sample. Together these findings suggest that pregnancy may create greater difficulties for the delivery of depression care to women receiving Medicaid benefits than for those in private HMOs. Because depression care delivery in pregnancy appears to vary by insurance status, these obstacles might be reduced through system changes, perhaps by adopting care models utilized in private HMOs. Further research is needed to better understand the factors influencing this apparent disparity in care delivery. These results are relevant to the developing field of maternal depression care and provide the first estimate of the magnitude of the obstacle that pregnancy creates to care for ongoing depression among women receiving Medicaid benefits.

A number of factors may contribute to discontinuation of care for depression during pregnancy and postpartum. There is concern among women and physicians that antidepressant medications can harm the fetus and infant ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ). In the postpartum period, women who breastfeed may also be reluctant to risk exposing their infants to antidepressants present in their breast milk. However, although psychotherapy also effectively treats depression, we found that the number of outpatient visits for depression care, and not just prescriptions for antidepressant medication, was reduced, which suggests that reduction in care was not attributable simply to concerns about exposing the fetus and infant to medication.

Transitions in care providers for women who become pregnant are also likely to contribute to disruption in care for depression. Women generally change to new health care providers when they begin prenatal care, and the relationship with their prepregnancy providers may not resume after giving birth. This period of transition can stretch from pregnancy through the first year postpartum, potentially creating an 18- to 24-month disruption in establishment of a medical home. This disruption may be exacerbated because prenatal and pediatric care providers are less comfortable than other primary care physicians with providing depression care to these women ( 33 , 34 , 35 ). Competing demands in this busy period of early motherhood may also make it more difficult for women to maintain ongoing relationships with specialty mental health providers.

The significance of these reductions in care for depression lies in the morbidity associated with depression in the perinatal period. Relapse of depression is high in pregnancy, with approximately 43% of women who are in remission at the time of becoming pregnant experiencing relapse; however, this rate is much higher (68%, or a hazard ratio of 5) among women who discontinue antidepressants compared with those who continue use ( 9 ). Depression symptomatology is also associated with preterm birth and with low birth weight ( 3 , 4 , 38 ). In addition, untreated postpartum depression is associated with poor parenting practices and infant behavioral development ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 39 ). Risk of psychopathology among infants is reduced by effective depression treatment of their mothers ( 8 ). Together these factors call for increased attention to the delivery of depression care to these vulnerable women.

We found that white women who became pregnant had a greater reduction in outpatient visits for depression than pregnant nonwhite women. This interaction of pregnancy status and race on care utilization has not been previously documented. Although the factors underlying this association should be more fully explored, nonwhite women may have a higher threshold for initiating treatment for depression, making them less vulnerable to disruption of care. The finding that pregnant white women had less of a relative reduction in antidepressant use than pregnant nonwhite women during the postpartum period may indicate differences in access or cultural differences in the acceptability or desirability of antidepressants across these racial-ethnic groups. Similarly, the protective effect of receiving cash assistance on the number of depression care visits may be related to access issues.

This work has several limitations. First we relied on billing and reimbursement data that were not generated originally for the purpose of analytic research. The few conditions that were available for matching the cohorts may not address important differences between these groups. The severity of depression among the women included in the analyses also could not be determined. However, in other studies of depression similar sources of data have been widely utilized and provide accurate measures of depression care, particularly with large samples. Prospective longitudinal research is needed to confirm and extend our findings. The data analyzed also span a two-year period that occurred more than nine years ago and may not reflect changes in practice that have occurred since. Recent studies of care for depression, however, indicate that relatively small changes to care delivery in pregnancy have occurred in the interim, suggesting that these results likely reflect current practices ( 14 ). Medicaid claims data also cannot distinguish among the possible causes of the pregnancy-related decline in depression care described above. Despite these limitations, the results strongly indicate that more attention should be paid to identifying and reducing the obstacles to care faced by women with depression who are Medicaid beneficiaries and who become pregnant.

Conclusions

In summary, we found evidence that pregnancy greatly reduces the care of depression among women receiving Medicaid and that this reduction in care persists for at least four months postpartum. Reduction in depression care occurred in use of antidepressants as well as in number of outpatient visits for depression, suggesting that concerns over fetal exposure to medications do not by themselves account for this drop in care utilization. Given the association of maternal depression with poor outcomes for the mother and infant, further efforts are warranted to identify means of overcoming obstacles to care and to increase depression treatment levels in this critical period for both the mother and infant.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by grants 5R01-MH061992 and 1R03-MH074750-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by grant 1K23-HD048915-01A2 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1994Google Scholar

2. Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, et al: Perinatal Depression: Prevalence, Screening Accuracy, and Screening Outcomes. Report no 119. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005Google Scholar

3. Hoffman S, Hatch MC: Depressive symptomatology during pregnancy: evidence for an association with decreased fetal growth in pregnancies of lower social class women. Health Psychology 19:535–543, 2000Google Scholar

4. Orr ST, James SA, Blackmore Prince C: Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and spontaneous preterm births among African-American women in Baltimore, Maryland. American Journal of Epidemiology 156:797–802, 2002Google Scholar

5. Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE: The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Archives of Women's Mental Health 6:263–274, 2003Google Scholar

6. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:50–76, 1990Google Scholar

7. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, et al: Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1001–1008, 2006Google Scholar

8. Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al: Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA 295:1389–1398, 2006Google Scholar

9. Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al: Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA 295:499–507, 2006Google Scholar

10. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al: Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:57–65, 2003Google Scholar

11. Skaer TL, Sclar DA, Robison LM, et al: Trends in the rate of depressive illness and use of antidepressant pharmacotherapy by ethnicity/race: an assessment of office-based visits in the United States, 1992–1997. Clinical Therapeutics 22:1575–1589, 2000Google Scholar

12. Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC: Recent core of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Google Scholar

13. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55–61, 2001Google Scholar

14. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al: Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 65:805–815, 2008Google Scholar

15. Wisner KL, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard H, et al: Pharmacologic treatment of depression during pregnancy. JAMA 282:1264–1269, 1999Google Scholar

16. Ferreira E, Carceller AM, Agogue C, et al: Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine during pregnancy in term and preterm neonates. Pediatrics 119:52–59, 2007Google Scholar

17. Levinson-Castiel R, Merlob P, Linder N, et al: Neonatal abstinence syndrome after in utero exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in term infants. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 160:173–176, 2006Google Scholar

18. Oberlander TF, Grunau RE, Fitzgerald C, et al: Pain reactivity in 2-month-old infants after prenatal and postnatal serotonin reuptake inhibitor medication exposure. Pediatrics 115:411–425, 2005Google Scholar

19. Bar-Oz B, Einarson T, Einarson A, et al: Paroxetine and congenital malformations: meta-analysis and consideration of potential confounding factors. Clinical Therapeutics 29:918–926, 2007Google Scholar

20. Berard A, Ramos E, Rey E, et al: First trimester exposure to paroxetine and risk of cardiac malformations in infants: the importance of dosage. Birth Defects Research Part B: Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology 80:18–27, 2007Google Scholar

21. Davis RL, Rubanowice D, McPhillips H, et al: Risks of congenital malformations and perinatal events among infants exposed to antidepressant medications during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety 16:1086–1094, 2007Google Scholar

22. Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al: Use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. New England Journal of Medicine 356:2684–2692, 2007Google Scholar

23. Weissman AM, Levy BT, Hartz AJ, et al: Pooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1066–1078, 2004Google Scholar

24. Clark R, Tluczek A, Wenzel A: Psychotherapy for postpartum depression: a preliminary report. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73:441–454, 2003Google Scholar

25. Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, et al: Controlled trial of the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of post-partum depression: 2. impact on the mother-child relationship and child outcome. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:420–427, 2003Google Scholar

26. O'Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, et al: Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:1039–1045, 2000Google Scholar

27. Milgrom J, Negri LM, Gemmill AW: A randomized controlled trial of psychological interventions for postnatal depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 44:529–542, 2005Google Scholar

28. Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al: The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. General Hospital Psychiatry 31:403–413, 2009Google Scholar

29. ACOG Committee: Opinion no 354: treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology 108:1601–1603, 2006Google Scholar

30. Atrash HK, Johnson K, Adams M, et al: Preconception care for improving perinatal outcomes: the time to act. Maternal Child Health Journal 10:S3–S11, 2006Google Scholar

31. Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al: Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care—United States: a report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recommendations and Reports 55:1–23, Apr 21, 2006Google Scholar

32. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2006Google Scholar

33. LaRocco-Cockburn A, Melville J, Bell M, et al: Depression screening attitudes and practices among obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstetrics and Gynecology 101:892–898, 2003Google Scholar

34. Hill LD, Greenberg BD, Holzman GB, et al: Obstetrician-gynecologists' attitudes towards premenstrual dysphoric disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology 22:241–250, 2001Google Scholar

35. Dietrich AJ, Williams JW Jr, Ciotti MC, et al: Depression care attitudes and practices of newer obstetrician-gynecologists: a national survey. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 189:267–273, 2003Google Scholar

36. Dietz PM, Williams SB, Callaghan WM, et al: Clinically identified maternal depression before, during, and after pregnancies ending in live births. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1515–1520, 2007Google Scholar

37. Song D, Sands RG, Wong Y-L: Utilization of mental health services by low-income pregnant and postpartum women on medical assistance. Women's Health 39:1–24, 2004Google Scholar

38. Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, et al: The Preterm Prediction Study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks' gestation—National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 175:1286–1292, 1996Google Scholar

39. Chung EK, McCollum KF, Elo IT, et al: Maternal depressive symptoms and infant health practices among low-income women. Pediatrics 113:e523–e529, 2004Google Scholar