CBT and Recovery From Psychosis in the ISREP Trial: Mediating Effects of Hope and Positive Beliefs on Activity

In recent years, a move away from traditional conceptualizations of recovery from severe mental illness has been observed. This has resulted in a more dimensional approach to recovery, with a broader focus on psychological well-being and functional outcomes, as opposed to a sole emphasis on symptom reduction. Much of this development has been stimulated by the recovery movement, a service user-led approach that supports each individual's potential for recovery and emphasizes the importance of hope, meaningful outcomes, and personal experience ( 1 ). The importance of social outcomes is also highlighted in the position statement on recovery by the American Psychiatric Association ( 2 ), which states that "the concept of recovery emphasizes a person's capacity to have hope and lead a meaningful life" and suggests that treatment should be guided by "attention to life goals and ambitions."

As a result, the number of studies that adopt social functioning as a primary outcome has increased. Trials of supported employment have highlighted the importance of interventions to improve functional outcomes of individuals recovering from psychosis ( 3 ). However, these studies often focus on engagement in work and education and ignore other dimensions of recovery, such as hope and positivity. It has been argued that more emphasis should be placed on inducing positive self-concept and instilling hope and realistic optimism, particularly among individuals for whom supported employment is not effective. Moreover, it has been suggested that integrating ideas from positive psychology ( 4 ), in which the focus is on mental well-being rather than mental illness, may help to reduce the stigma of having a mental health problem ( 5 ). Resnick and colleagues ( 6 ) have argued that the next step is to develop recovery-focused interventions encompassing these values and to examine empirically whether such interventions are efficacious and have a positive impact on functional outcomes.

Service users who provide accounts of recovery from psychosis frequently report feelings of disempowerment and loss of hope. This feeling of hopelessness is often instilled at a very early stage of the illness and is hypothesized to be related to the traditional idea that individuals with psychosis, particularly schizophrenia, will experience an inevitable and progressive downhill course ( 7 ). Overcoming this preconception is one of the main elements of recovery outlined in service user literature, a particular focus of which is recovering self-identity and regaining a sense of control and mastery over one's life. In a review of this literature, Anthony ( 1 ) defined recovery as "a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with the limitations caused by mental illness."

Personal resilience, self-esteem, and hope are highlighted as important components of functional recovery from psychosis. Indeed, "renewing hope and commitment," "acceptance," and overcoming the "interpersonal effects" of psychosis feature heavily in user-defined criteria for recovery ( 7 ). It has been proposed that these themes may be important mediators of functional recovery, and it has also been argued that the themes should be central components in recovery-oriented services ( 1 ). However, more empirical research is needed. Many studies investigating the role of hope and positivity are based on personal narratives of the recovery process. Approaches focused on evidence-based practices rarely consider such concepts, possibly because of problems with measurement. Therefore, despite theoretical studies highlighting hope and positive self-concept as key recovery themes, we know of no studies that have investigated the effect of a recovery-focused intervention on these constructs or that have empirically examined their role as mediators of functional outcome.

The Improving Social Recovery in Early Psychosis (ISREP) study was a randomized controlled trial designed to investigate the efficacy of a new psychosocial intervention to improve social recovery in early psychosis and severe affective disorder ( 8 ). The intervention—social recovery-oriented cognitive-behavioral therapy (SRCBT)—is guided by a cognitive model of recovery that suggests that gains in activity may be mediated by facilitating changes in motivation and hope and in positive beliefs about self and others. The therapy has a specific focus on instantiating positive self-concept and promoting hope for the future. This is in contrast to traditional CBT approaches, which focus on self-defeating negative cognitions ( 9 ). In a recent study, SRCBT was found to have a significant and positive effect on the functional outcome of hours spent each week in structured activity ( 8 ).

It is well established that randomized controlled trials provide gold-standard methodology to test the effectiveness of treatments. However, there is an increasing emphasis on the use of this approach to examine the process of treatment as well as outcome ( 10 ). The study reported here examined the effect of SRCBT on hope and positive beliefs about self and others. It also examined the role of these dimensions as mediators of functional outcome. In line with the cognitive model underlying the intervention, it was hypothesized that the provision of SRCBT would decrease feelings of hopelessness and increase positive beliefs about self and others. It was also hypothesized that changes in hopelessness and positive beliefs would be specifically associated with improvements in outcome.

Methods

The study was a secondary analysis of data from the ISREP study ( 8 ), a single-blind randomized controlled treatment trial. The study compared individuals who received SRCBT (N=35) with those in a treatment-as-usual control group (N=42).

Seventy-seven participants were recruited from secondary mental health services in the East Anglia region of the United Kingdom from 2004 to 2007. The sample had a mean age of 29.0±6.8 years. Fifty-five participants (71%) were male, and 22 (29%) were female. Fifty participants (65%) had received a diagnosis of nonaffective psychosis (predominantly schizophrenia), and 27 (35%) had a diagnosis of affective psychosis (predominantly bipolar disorder). Mean±SD duration of illness was 4.8±2.3 years, and mean length of unemployment was 209±182 weeks. [An appendix with further information about the ISREP study and a CONSORT diagram is available as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatrtyonline.org .]

The primary outcome that was used in the ISREP trial was weekly hours in structured activity, which was assessed with the Time Use Survey ( 11 ). The survey is a semistructured interview in which the participant is asked about how he or she has spent time over the past month. Activities inquired about include paid or voluntary work, education, leisure, sports or hobbies, socializing, housework or chores, and child care. Information gathered is used to calculate average hours per week spent engaged in structured activity.

Hopelessness was assessed with the Beck Hopelessness Scale ( 12 ), a 20-item self-report scale designed to assess three main aspects of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and expectations. Positive and negative beliefs about self and others were assessed with the Brief Core Schema Scales ( 13 ), a 24-item self-report instrument that uses a 5-point rating scale—0, belief not held, to 4, believe it totally. Four scores are obtained: negative self (six items; example, "I am bad"), positive self (six items; example, "I am talented"), negative others (six items; example, "Other people are hostile"), and positive others (six items; example, "Other people are accepting").

Participants were assessed at two time points by a researcher who was blind to treatment allocation. The baseline assessment occurred after participants had provided written consent to take part in the study and before randomization. The posttreatment assessment took place at the end of the treatment period, approximately nine months after the baseline assessment. The study was approved by local ethics committees, and all participants gave written consent to participate after a formal explanation of the study.

All analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 14. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were used to test the significance of differences in outcome between the SRCBT and control groups for time use, hopelessness, and schematic beliefs. A separate ANCOVA was conducted for each outcome and mediating variable (that is, time use, hopelessness, and beliefs about self and others) by using the posttreatment score on the measure as the dependent variable. Allocation to treatment, treatment center, and diagnosis were used as fixed factors. Baseline score on the measure in question, length of unemployment, and baseline level of psychotic symptoms were included as covariates. This decision was based on an a priori hypothesis that length of unemployment was likely to be associated with social recovery and the finding that level of baseline psychotic symptoms predicted dropout from the study.

A further set of ANCOVA models were used to examine the effect of hope and positive beliefs about self and others as mediators of change in functional outcome in the context of SRCBT. For each ANCOVA, the number of weekly hours in structured activity at posttreatment was the dependent variable, with baseline hours in structured activity as a covariate. Allocation to treatment and change in the mediating variable over the course of the trial were included as explanatory variables. A significant interaction between allocation and change in hope or positive beliefs was interpreted as suggesting that hope or positive beliefs may mediate the effect of SRCBT on functioning (that is, the intervention may enhance change in those variables).

Analyses were initially conducted with data from the 77 participants. To examine an a priori hypothesis that social recovery may follow a different course for individuals with affective and nonaffective psychosis, further analyses of diagnostic subgroups were conducted.

Results

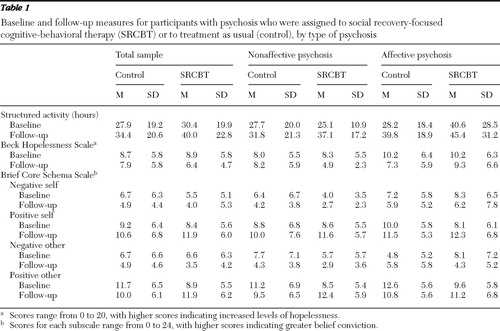

As shown in Table 1 , participants in both SRCBT and treatment as usual experienced large improvements in activity and on other variables. In the combined affective and nonaffective psychosis group, ANCOVA analyses highlighted a significant main effect of treatment on positive beliefs about self (F=5.10, df=1 and 70, p=.03) and on positive beliefs about others (F=5.61, df=1 and 70, p=.02). Moreover, in the nonaffective psychosis subgroup, there was a significant main effect of SRCBT on hours in structured activity (F=11.73, df=1 and 44, p=.001) and a trend suggesting a main effect of treatment on hopelessness (F=3.79, df=1 and 44, p=.06). No effect of SRCBT on negative beliefs about self and others was found in either the combined group or the nonaffective psychosis group.

|

A significant interaction was found between receipt of SRCBT and change in positive beliefs about self (F=18.11, df=1 and 72, p<.001). Thus the mediation analysis suggested that changes in positive beliefs about self were associated with increased levels of activity in the SRCBT group. This implies a moderating effect of the intervention on this variable. No significant interactions were found between receipt of SRCBT and changes in hopelessness, positive beliefs about others, or negative schematic beliefs.

Discussion

The findings indicate a significant effect of SRCBT in improving positive beliefs about self and others. A trend was noted suggesting that SRCBT had an effect on reducing feelings of hopelessness among individuals with nonaffective psychosis. In addition, changes in positive beliefs about self predicted improvements in levels of activity in the SRCBT group, suggesting that positivity is a mediator of functional outcome. These findings support the cognitive model underpinning the intervention, which has an important focus on deliberately fostering positive self-esteem in the context of developing meaningful personal goals and working toward achieving them by adopting new social activities.

The findings support those of previous studies that highlight an important role for hope and positive self-concept in the recovery process. Moreover, the study reported here provides a bridge between consumer-oriented and evidence-based practice approaches to investigating and defining recovery. Consumer-oriented approaches highlight the importance of "renewing hope" and addressing the "interpersonal effects" of psychosis. It is argued that these constructs are important in the recovery process, fueling motivation for change ( 7 ). However, the subjective nature of personal narratives makes the role of hope and positivity difficult to ascertain by using qualitative methods. In addition, such constructs are rarely included as outcomes in randomized controlled trials or other evidence-based practice approaches. This is the first study to our knowledge to empirically investigate the role of these previously suggested mediators in enhancing social recovery from psychosis.

The findings of this study have important clinical implications and suggest that promoting positive self-concept should be a key focus of recovery-oriented interventions. This is in contrast to traditional CBT approaches, which have a tendency to focus on self-defeating negative cognitions ( 9 ). Targeting negative schematic beliefs is an important feature of CBT for individuals with positive psychotic symptoms, particularly paranoia ( 13 ). This study also suggests that fostering positive beliefs about self and others may be an important feature of therapy for social rather than symptomatic recovery. A recent study by Yanos and colleagues ( 14 ) suggested that stigma has a negative effect on functional outcome because of its adverse impact on hope and self-esteem. In line with these findings, it seems likely that reducing feelings of stigma and promoting a positive self-concept—both key aims of the SRCBT approach—would have a positive effect on functional outcome, as suggested by this study. The aim of the ISREP trial was to develop an intervention that deliberately linked improvements in time spent in meaningful activity with improvements in psychological well-being and self-esteem while managing risk of sensitivity to stress. The mediator results are consistent with achievement of these aims.

A number of considerations should be borne in mind when interpreting the results of this study. First, the sample was not large enough to draw formal conclusions. The ISREP trial was designed to be exploratory rather than confirmatory and lacked power to detect effects, particularly within diagnostic subgroups. Moreover, the generalizability of the findings to a wider population of individuals with psychosis is unknown and requires further investigation. A further limitation concerns the statistical methods used to conduct the mediation analyses. In line with traditional approaches, these analyses relied on the assumption that no hidden confounding exists between mediator and outcome variables; the approach also ignores the presence of measurement error in the assessment of mediator and outcome variables. Although these factors are problematic, the same criticisms apply to other studies assessing mediation using traditional approaches.

The study reported here provides a suggestion of future mediation hypotheses and also confirms the theoretical underpinning of the intervention tested. That said, in order to control for potential confounding, newer mediation approaches need to be adopted, such as those outlined by Dunn and Bentall ( 15 ). These methods require large samples and identification of potential confounders in the design stage of the study, which was beyond the scope and power of this study but which should be borne in mind for future study designs. In addition, it is possible that increased activity levels had an effect on hope and positivity, and thus the exact mechanism of change warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

Theoretical parallels have been drawn between the recovery movement and positive psychology, and it has been suggested that recovery-oriented approaches should focus on empowering people to enhance what is good in their lives, rather than attending to what is wrong ( 5 ). However, this study is the first to provide empirical data that an intervention that deliberately seeks to foster positive self-esteem can have significant benefits for an individual's self-concept, which are directly related to improvements in meaningful activity and thus to social recovery from psychosis.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for the trial was provided by a trial platform grant from the Medical Research Council (grantholders: Prof. David Fowler, Prof. Peter Jones, Prof. Miranda Mugford, Dr. Iain Macmillan, and Dr. Tim Croudace). The authors appreciate the involvement of the trial therapists, who included Michelle Painter, Tony Reilly, Dorothy O'Connor, Annabella Houlden, Neil Harmer, Cas Wright, Mark Wright, Ian Bell, Nick Whitehouse, and Patrick Wymbs. The authors also acknowledge Carolyn Crane (research nurse) and U.K. Mental Health Research Network staff who provided assistance with recruitment and assessment.

The authors report no competing interests

1. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service in the 1990s. Psychological Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Google Scholar

2. Use of the Concept of Recovery: Position Statement. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Association, 2005Google Scholar

3. Drake RE, Becker DR, Clark RE, et al: Research on the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:289–301, 1999Google Scholar

4. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M: Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psychologist 55:5–14, 2000Google Scholar

5. Resnick SG, Rosenheck R: Recovery and positive psychology: parallel themes and potential synergies. Psychiatric Services 57:120–122, 2006Google Scholar

6. Resnick SG, Fontana A, Lehman A, et al: An empirical conceptualization of the recovery orientation. Schizophrenia Research 75:119–128, 2005Google Scholar

7. Davidson L: Living Outside Mental Illness: Qualitative Studies of Recovery in Schizophrenia. New York, New York University Press, 2003Google Scholar

8. Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Painter M, et al: Cognitive behaviour therapy for improving social recovery in psychosis: a report from the ISREP MRC Trial Platform study (Improving Social Recovery in Early Psychosis). Psychological Medicine 39:1–10, 2009Google Scholar

9. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al: Cognitive Therapy for Depression. New York, Guilford, 1979Google Scholar

10. Green J, Dunn G: Using intervention trials in developmental psychiatry to illuminate basic science. British Journal of Psychiatry 192:323–325, 2008Google Scholar

11. The United Kingdom 2000 Time Use Survey—Technical Report. London, Office for National Statistics, 2003. Available at www.statistics.gov.uk/timeuse/default.asp Google Scholar

12. Beck AT, Steer RA: Beck Hopelessness Scale Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1988Google Scholar

13. Fowler D, Freeman D, Smith B, et al: The Brief Core Schema Scales (BCSS): psychometric properties and associations with paranoia and grandiosity in non-clinical and psychosis samples. Psychological Medicine 36:1–11, 2006Google Scholar

14. Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, et al: Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 59:1437–1442, 2008Google Scholar

15. Dunn G, Bentall R: Modeling treatment-effect heterogeneity in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions (psychological treatments). Statistics in Medicine 26:4719–4745, 2007Google Scholar