Promoting Recovery in Long-Term Institutional Mental Health Care: An International Delphi Study

Deinstitutionalization in psychiatric and social care has been occurring at different rates across Europe over the past 20 years. This movement has shown that people with severe mental health problems have multiple residential, vocational, educational, and social needs and aspirations ( 1 ), which in turn has generated new conceptualizations of how services should be organized and delivered. The guiding vision of service provision for this group has become the recovery model ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ), in which recovery is viewed as a lifelong process that involves an indefinite number of incremental steps in various life domains and in which the mental health problem is seen as only one aspect of the whole person.

There is broad agreement among service users and providers, as well as among researchers and policy makers, that key attributes of a recovery-oriented model include treatment approaches that are negotiated between service users and practitioners and that promote empowerment, self-management, dignity, and reclaiming identity (including physical, sexual, spiritual, group, and cultural identity) ( 5 ). The ethos of a recovery approach is one of hope and optimism, providing a context in which individuals are supported in engaging in meaningful activity (such as education and employment), overcoming the stigma of mental illness, and developing self-awareness, self-acceptance, and self-esteem ( 6 , 7 , 8 ). However, although the guiding principles and goals of a recovery approach are in place, there is less certainty about the degree of consensus among various stakeholders in different contexts—both national and social—about their relative weight and importance or about the specific, concrete components of care that are most effective in achieving recovery goals ( 9 ). This uncertainty is particularly tested—but no less relevant—in institutional care settings.

Other authors in the DEMoBinc Group (Development of a European Measure of Best Practice for People With Long Term Mental Illness in Institutional Care)

Tatiana L. Taylor, B.A., M.Sc., Research Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London, United Kingdom

Matthias Schützwohl, Ph.D., and Mirjam Schuster, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital, Technical University of Dresden, Germany

Jorge A. Cervilla, M.D., Ph.D., CIBERSAM, University of Granada, Section of Psychiatry and Institute of Neurosciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Granada, Spain

Paulette Brangier, Psy.D., Centre of Biomedical Research, University of Granada, Spain

Jiri Raboch, M.D., and Lucie Kališova, M.D., Psychiatric Department of the First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

Georgi Onchev, M.D., Ph.D., and Anita Fercheva, M.Sc., Department of Psychiatry, Medical University Sofia, Bulgaria

Roberto Mezzina and Pina Ridente, Mental Health Department of Trieste, Italy

Durk Wiersma, Prof. Ph.D., and Annemarie Caro-Nienhuis, M.Sc., Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Centre Groningen, the Netherlands

Andrzej Kiejna, M.D., and Patryk Piotrowski, Ph.D., M.D, Department of Psychiatry, Wroclaw Medical University, Wroclaw, Poland

Elias Tzavelas and Xeni Asimakopoulou, University Mental Health Research Institute, Athens, Greece

José Caldas-de-Almeida, M.D., Ph.D., and Graça Cardoso, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Mental Health, Faculty of Medical Sciences, New University of Lisbon, Portugal

Michael King, M.D., Ph.D., Research Department of Mental Health Sciences, University College London, England, United Kingdom

This Delphi study was embedded in the early phases of a larger project funded by the European Commission—the DEMoBinc Project (Development of a European Measure of Best Practice for People With Long Term Mental Illness in Institutional Care) ( 10 ) that involved a consortium of clinical academics with a specialty in long-term mental health care (the DEMoBinc group) in ten European countries: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, England, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Spain. The research call was to develop a methodology for assessing and reviewing living situations, care, and treatment practices in psychiatric and social care institutions for persons with mental illness in the European Union, with a particular focus on human rights and the protection of the dignity of residents. The project team adopted a recovery orientation as being the most appropriate overarching framework for these purposes.

The Delphi study had three main objectives. First, we wanted to identify the specific items of care that key stakeholders regard as most important in promoting recovery of people in long-term institutional care. The second objective was to measure consensus between and across stakeholder groups and countries regarding the relative importance of those items in promoting recovery. Third, the study aimed to organize items of high importance and on which consensus was high into a conceptual framework of domains of care.

Methods

The study used a Delphi methodology. This is a well-established and systematic way of collecting, organizing, reviewing, and revising the opinions of panels of individuals who generally do not meet face to face ( 11 , 12 ), although some studies conduct an introductory meeting for participants or a feedback conference at the end of the process. It is an iterative process that allows equal weighting of participants' views and renders the process of determining priorities transparent. The method involves gathering the opinions of each of the panel's members independently, usually by a questionnaire, and then providing all this information to each panel member as feedback ( 13 ). Individuals have the opportunity to refine their judgments on the basis of the feedback. Participants' anonymity is generally preserved to avoid undesirable psychological effects. The method has been used frequently with expert panels and is especially useful as a tool for governing effective communication in a group of people, uninhibited by group dynamics, and for assessing consensus about an issue in a time-efficient way ( 14 ).

The study employed a series of conventional three-round Delphi exercises with four separate expert groups (service users, mental health professionals, caregivers, and advocates) in each of the ten participating European centers (total of 40 groups). This enabled us to compare the independent opinions of the stakeholder groups across countries. Researchers aimed to recruit ten to 12 respondents for each group. In the first round of the exercise, each respondent was asked to suggest ten answers to a specific, structured question: "In your view, what most helps recovery for people with long-term mental health problems in institutional care?"

Individual responses generated in this round were then fed back to the respondent group, and members rated their importance. Finally, the respondents rated the items again in light of information about their group's response as a whole.

Participant inclusion criteria

Participants were selected on the basis of their broad experience of psychiatric or social care institutions. As far as possible, in keeping with the project's overarching framework, participants selected were known to have a recovery orientation—that is, a view of the institutional setting as an environment that supports people in moving back into the community. In each country researchers sought as representative a population as possible. The mental health professionals group was multidisciplinary. When possible, service users and caregivers were selected on the basis of their experience in representing national or regional organizations relevant to service users or caregivers. Advocates were defined as individuals who campaign and advocate for the rights of service users and caregivers, often with a wider organizational responsibility for advocacy.

Procedure

Ethics approval for the study was sought but deemed not to be required by relevant ethics committees in the ten countries. The study was carried out between August 2007 and March 2008. Potential respondents were identified by a cascade method of known contacts and direct approaches to relevant organizations—statutory, professional, and independent. Delphi questionnaires were circulated by e-mail, post, or fax. Researchers at each center listed the items from the completed round 1 questionnaires for each group separately so that participants could see their own group's overall list and their individual list within it. At this stage, grouping similar items was avoided because it would have involved the researchers' personal judgments and might have guided respondents.

To preserve subtle nuances of meaning, items that appeared similar were retained unless the wording was identical. When a particular item was unclear, the participant was asked for clarification. Items that were too lengthy or otherwise unsuitable for rating on the round 2 questionnaire were edited by use of three criteria: singularity, maximum length, and maximum fidelity. For singularity, when a single response contained two suggestions, for example, "flexible visiting hours and a pleasant family-friendly visiting environment," they were separated into two items. A maximum length of 1.5 lines was usually achieved by retaining the concrete recommendation for practice but excluding the longer explanation. For example, "having a fairly rigid ward routine, I really appreciated the ward policy of having a bedtime or `lights out' time. This gave a sense of structure and was very different to what I'd experienced on acute wards" was shortened to "having a fairly rigid ward routine to give a sense of structure." Finally, items were edited for clarity, applying a principle of maximum fidelity to the original wording and idea.

The resulting list formed the basis of the round 2 questionnaires. Participants were asked to rate each of the listed items generated by members of their group on a scale of 1, unimportant, to 5, essential, in terms of the item's contribution to recovery. In accordance with Delphi methodology, median scores were then calculated for each item. In round 3, participants were provided with their own ratings from round 2 along with their group's median rating for each item. They were then asked to rate each item again in the light of the information on median ratings and to comment when their new rating differed from the median by more than 2 points.

Analysis

A database template in SPSS Version 15 for Windows was developed and circulated to all centers. Items from each center were collated by type of stakeholder group, and median and consensus ratings were determined for each type of group. Respondents were considered to be in consensus if their score was within ±1 of their group's median. Each center received feedback on its own results. Items rated essential (score of 5) or very important (score of 4) with at least 80% within-group consensus were then organized into domains by using a heuristic method reinforced by clinical judgment and experience. Each item was reviewed by the first two authors. Those judged to fit well were grouped into clusters, overarching themes or domains were identified to describe clusters, and domains continued to be identified until all items were placed. The resulting domains and their item allocation were discussed and agreed upon with the London authors (at St. George's, from where the Delphi study was being coordinated, and at University College, from where the wider DEMoBinc Project was being coordinated).

All qualifying items were subsumed into one or more of the chosen domains. When an item clearly belonged in two domains, it was included in both; for example, "Being treated with respect by staff, as an equal person rather than a diagnosis" was included under both the "human rights" and the "staff attitudes" domains. Finally, to focus on the most important domains, we identified items rated essential with 100% within-group consensus and explored the domains that were included by use of this highest threshold of importance.

Results

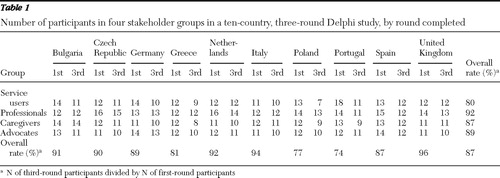

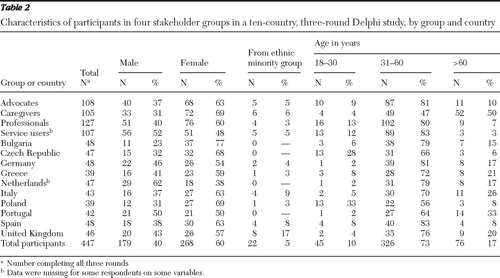

All countries recruited the required number of participants who met inclusion criteria for all groups. The overall participant retention rate over the three rounds of the Delphi was 87% ( Table 1 ). Data on respondent characteristics are presented in Table 2 .

|

|

Generation of domains

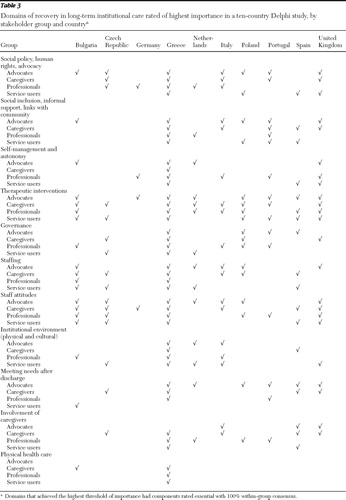

From the 4,098 items of care contributed by the Delphi respondents, 3,187 (78%) achieved median scores of 4 or 5 with at least 80% group consensus. Notwithstanding the high median and consensus ratings, 39% of all items received a score of 1 or 2, indicating that participants were willing to use the full spread of ratings when they deemed it appropriate. Service users employed a wider spread of responses than any other group (51% of items were rated 1 or 2); advocates used the narrowest spread (32% of items were rated 1 or 2). Items achieving high median ratings plus high consensus ratings—many of which were similar across groups—were organized into 11 broad domains of care: social policy, human rights, and advocacy; social inclusion; self-management and autonomy; therapeutic interventions; governance; staffing; staff attitudes; institutional environment (physical and cultural); meeting needs after discharge; involvement of caregivers; and physical health care. [A table listing the 11 domains and the components of care allocated to them is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Ratings by country and stakeholder group

There was strong cross-country consensus about the importance of all the domains. Although individual items varied across groups and countries, at least one of the four stakeholder groups in all ten participating countries reached at least 80% consensus on items that were rated as essential or very important in each of the 11 domains.

Table 3 shows which domains achieved the highest threshold of importance (domains containing items rated essential with 100% within-group consensus), by group and country. Across all 40 groups, 391 items were included in this analysis. Most domains were represented by one or more groups from the majority of countries (median domains per country, 9.5; range, 4 (Germany) to 11 (Greece). Differences between the stakeholder groups were fairly modest; for each domain, the four stakeholder groups had similar ratings across all ten countries. Three domains—therapeutic interventions; staffing attitudes; and social policy, human rights, and advocacy—reached the highest threshold of importance with one or more stakeholder groups in all ten countries. The highest-ranking domain was therapeutic interventions; it achieved the highest threshold in 30 of the 40 stakeholder groups across countries. However, Table 3 shows that there was considerable agreement with regard to the importance of most of the other domains as well; all domains were ranked at the highest threshold of importance by at least one stakeholder group in at least seven of the ten participating countries. The most notable exception was the physical health care domain, which achieved the highest threshold of importance in only two of the ten countries. Two domains that are generally regarded to be highly associated with recovery-oriented practice—social inclusion and self-management and autonomy—achieved the highest threshold of importance in at least one stakeholder group in eight of the ten countries.

|

Discussion

Main findings

Many of the items of care identified as important by key stakeholders in this study are closely related to so-called markers of recovery ( 15 , 16 )—for example autonomy and self-management, social inclusion, dignity, hope, meaningful activity, maintaining social and intimate relationships, and overcoming stigma. However, although such themes are clearly relevant to institutional care settings ( 17 , 18 ), they did not always emerge as being the most important. For example, autonomy and physical health care achieved the highest threshold of importance in only 13 (33%) and four (10%), respectively, of the 40 respondent groups.

It is noteworthy that the domains that achieved the highest threshold of importance may be more commonly understood as representing a more conventional, clinical model of recovery. The domain with the highest rating was therapeutic interventions. This finding could be regarded as unsurprising among groups with considerable experience of serious mental illness in institutional care settings, for whom components of care within the domain of therapeutic interventions arguably form the very basis and raison d'être of health care. Nonetheless, the top ranking of therapeutic interventions in the context of stakeholders with a recovery orientation and in groups of service users, caregivers and advocates, and mental health professionals was somewhat unexpected. This finding suggests a medically oriented emphasis on delivering treatment and addressing symptoms rather than a broad view of recovery principles. This impression is lent further weight by the repeated reference within this domain, particularly by service users and caregivers, to the importance of appropriate and timely psychopharmacological treatment. Items in this category included developing new, more effective drugs; careful prescribing with attention to side effects and regular review of medication; and providing detailed information to service users about the benefits and effects of medication. It should be noted, however, that the importance of a whole-person, strengths-based approach to treatment was also emphasized, as were structured and meaningful occupation and a range of talking therapies and alternative specialist interventions.

The second most important domain concerned staff attitudes. This included building good therapeutic alliances and went further, laying particular stress on qualities of communication and interaction that were polite, honest, equal, attentive, respectful, accepting, and understanding. It is a salutary reminder—and somewhat sobering—that these attributes needed such prominent emphasis among respondents and were not taken for granted. Some groups, notably in Spain and Greece, went beyond these core qualities to promote client-professional relationships that are actively affectionate, tender, and loving. Similar concerns have been raised about a failure of health professionals in general medical services to deliver sensitive, humane care and to treat patients with dignity ( 19 ). These concerns have led to recent calls in the United Kingdom to promote a "compassionate care agenda" ( 20 ).

These findings correspond to those reported by others. A study aimed at defining views of various stakeholders about the characteristics of good community care found that highest priority was given to a trusting and stimulating relationship between clients and professionals and to provision of effective treatment tailored to individual needs ( 21 ). A systematic literature review conducted in relation to the study presented here found that the strongest evidence for components of care that promoted recovery in institutions was for specific interventions for the treatment of schizophrenia (medication, family psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and supported employment) and for positive therapeutic alliances ( 22 ). Although recovery-focused interventions were among the critical factors identified as contributing to the quality of institutional care, the strength of evidence supporting them was lower than for other components of care.

The modest differences between the four stakeholder groups were to some degree predictable; for example, caregivers valued caregiver involvement more than other groups, service users valued the quality of the institutional environment more than other groups, and advocates valued human rights and social inclusion more than other groups. More surprising were service users' relatively low emphasis on autonomy, mental health professionals' relatively low emphasis on factors related to staffing and postdischarge support, and the overall low emphasis on physical health care.

Limitations

Even though we asked study participants to identify components of institution-based care that were concrete and specific, some of the most highly rated items lacked these characteristics—for example, "high-quality psychiatric care," "satisfying basic social needs," and "empathy." Such axiomatic items will inevitably attract high ratings, but their generality makes them hard to operationalize and to measure. A further series of more targeted Delphi studies (for example, on social exclusion) could produce a more close-grained understanding. A further and perhaps related limitation of the study arose from participants' limited use of the full spread of ratings, despite the specific request to do so. This is a common problem in Delphi studies with research-naïve populations.

Another potential limitation is the subjugation of "minority" items to the will of the majority. Items that received the highest ranking from some individual respondents (for example, "having my spiritual needs catered for" and "being allowed to keep a pet") but failed to meet group median and consensus threshold criteria were lost to the final analysis.

Finally, sociodemographic characteristics of participants, particularly ethnicity, were not sufficiently representative of the populations of some countries, which limits the generalizability of our findings. It should also be noted that our results inevitably reflect the selected orientation and affiliations of our participants; results may have been different had we recruited stakeholders with other kinds of experience.

Strengths of the study

The study systematically elicited broad practice-based ways of promoting recovery in psychiatric institutions and measured consensus about their relative importance within and across different national settings and stakeholder groups. In giving a voice to stakeholder opinion, the study has provided an important counterbalance to the evidence available from clinical research. The combination of the Delphi approach and an international literature review has been one of the main strengths of the methodology of DEMoBinc. The combination made a useful contribution to the project's overall task of providing a means for an individual service to evaluate its own practice and enabling a comparison of practices across institutions and countries in ways that are valid and meaningful to those involved as well as rooted in an empirical evidence base.

Conclusions

Although domains and components of care related to recovery principles were viewed as important across stakeholder groups, the domain that most consistently received the highest consensus ratings was therapeutic interventions, which included a number of items associated with the medical model of treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support for this study from the European Commission (grant number SP5A-CT-2007-044088).

Dr. Raboch has received support from Zentiva K.S. (research grant), Medicom International (honoraria and travel grant), and Pfizer (travel grant). The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16(4):11–23, 1993Google Scholar

2. Allott P: Recovery; in Research and Development in Mental Health: Theory, Framework and Models. Edited by Sallah D, Clark M. Oxford, United Kingdom, Elsevier Science, 2005Google Scholar

3. Deegan PE: Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11(4):11–19, 1988Google Scholar

4. Spaniol L, Koehler M: The Experience of Recovery. Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1994Google Scholar

5. A Common Purpose: Recovery in Future Mental Health Services. Joint position paper 08, Care Service Improvement Partnership, Royal College of Psychiatrists, and the Social Care Institute for Excellence. London, Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2007Google Scholar

6. Deegan P: Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 19(3):91–97, 1996Google Scholar

7. Roberts G, Wolfson P: The rediscovery of recovery. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 10:37–47, 2004Google Scholar

8. Brown W, Kandirikirira N: Recovering Mental Health in Scotland: Report on Narrative Investigation of Mental Health Recovery. Glasgow, Scottish Recovery Network, 2006Google Scholar

9. Davidson L, O'Connell MJ, Tondora J, et al: Recovery in serious mental illness: a new wine or just a new bottle? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 36:480–487, 2005Google Scholar

10. Killaspy H, King M, Wright C, et al: Study protocol for the Development of a European Measure of Best Practice for People With Long Term Mental Illness in Institutional Care (DEMoBinc). BMC Psychiatry 9:36, 2009Google Scholar

11. Ambrosiadou B-V, Goulisoe DG: The Delphi method as a consensus and knowledge acquisition tool for the evaluation of the diabetes system for insulin administration. Medical Informatics and the Internet in Medicine 24:257–268, 1999Google Scholar

12. Reid WM, Pease J, Taylor RG: The Delphi technique as an aid to organization development activities. Organization Development Journal 8(3):37–42, 1990Google Scholar

13. Linstone HA, Turoff M: The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, Mass, Addison-Wesley, 1975Google Scholar

14. Fiander M, Burns T: A Delphi approach to describing service models of community mental health practice. Psychiatric Services 51:656–658, 2000Google Scholar

15. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura, J, et al: Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry 14:256–272, 2002Google Scholar

16. Schrank B, Amering M: Recovery in mental health [in German]. Neuropsychiatrie 21:45–50, 2007Google Scholar

17. Halpern LJ, Trachtman HD, Duckworth KS: From within: a consumer perspective on psychiatric hospitals; in Textbook of Hospital Psychiatry. Edited by Sharfstein SS, Dickerson FB, Oldham JM. Arlington, Va, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2009Google Scholar

18. Brookes N, Murata L, Tansy M: Guiding practice development using the Tidal Commitments. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 13:460–463, 2006Google Scholar

19. Chochinov H: Dignity and the essence of medicine: the A, B, C and D of dignity conserving care. British Medical Journal 334:184–187, 2007Google Scholar

20. Youngson R: Compassion in Healthcare: The Missing Dimension of Healthcare Reform? Futures Debate, paper 2. London, NHS Confederation, May 2008Google Scholar

21. Van Weeghel J, van Audenhove CM, Garanis-Papadatos T, et al: The components of good community care for people with severe mental illnesses: views of stakeholders in five European countries. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 28(3):274–281, 2005Google Scholar

22. Taylor T, Killaspy H, Wright C, et al: A systematic review of the international published literature relating to quality of institutional care for people with longer term mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry 9:55, 2009Google Scholar