Continuing Medication and Hospitalization Outcomes After Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York

Considerable evidence now supports the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ), but almost no research has addressed the questions of how long outpatient commitment should last ( 7 ) and what happens when this legal "leverage" is lifted ( 11 , 12 ). There are three basic positions regarding duration of court-ordered treatment ( 13 ). The first is that outpatient commitment should be a short, one-time "booster" to reengage consumers in a needed program of services; if reengagement succeeds, then services should continue on a voluntary basis. The second position is that outpatient commitment is a tool of leverage to maintain treatment adherence over a sustained period of time for persons who, because of the nature of their illness, are otherwise unwilling or unable to participate consistently in mental health services. The third position is that some individuals may benefit from shorter court orders, whereas for others a longer term is appropriate. For some, involuntary outpatient commitment may serve as a gateway to subsequent voluntary engagement in services, and for others, the threat of sanction for failing to comply with court-ordered treatment motivates continued adherence.

According to the first view, involuntary outpatient commitment orders should not be renewed for consumers who are engaged in services and doing well. In contrast, according to the second view, favorable outcomes under an involuntary outpatient commitment order are evidence that the court order is "working" and thus that it should be extended. The third position would hold that the question of extending an involuntary outpatient commitment order depends not only on treatment participation and outcomes under the court order but also on an assessment of the likelihood that any needed support for treatment will continue after expiration of the court order.

This article focuses on a specific context of involuntary outpatient commitment: New York's assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) program. New York's program is a form of involuntary outpatient civil commitment whereby a judge can order a person with mental illness who meets certain criteria to follow a court-ordered treatment plan in the community. The goals of this compulsory treatment are to facilitate participation in intensive, community-based case management services, which may then improve distal goals of increased community tenure and reduced hospitalization.

In the study reported here, we examined what happens after involuntary outpatient commitment is discontinued. Do consumers continue to possess their psychotropic medication in the community, and do they avoid hospitalization at the same levels achieved while they were under the court order? To what extent does the persistence of positive outcomes depend on the length of the court order and on the continuation of intensive services after the court order ends?

Methods

This project was approved by the institutional review boards of Duke University, Policy Research Associates, New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), and Biomedical Research Alliance of New York.

Sample

As described in the introduction to this special section ( 14 ) and reported in the other articles ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ), the evaluation of the AOT program used multiple sources of data to address several study objectives. Service encounter data were obtained for 3,609 individuals who received court-ordered outpatient treatment under the program and who were eligible for Medicaid at any time between January 1, 1999, and March 14, 2007. Data were incomplete for 33 persons, which left a sample of 3,576 AOT recipients.

Measures

Dependent variables. Psychiatric hospitalization data were obtained from two independent sources: Medicaid claims and OMH records of admissions to state psychiatric hospitals.

Medication possession was constructed with Medicaid pharmacy fill records. We calculated the number of days in a given month in which an individual had a supply of a prescribed psychotropic medication that was clinically appropriate for his or her current diagnosis. Consistent with prior research ( 20 , 21 , 22 ), months in which the filled supply of medication was enough to cover 80% of the days were considered high-possession months, compared with low-possession months when the filled supply would have covered less than 80% of the days. (Depot medication claims were coded as a complete fill for the given month.)

Independent variables. Current legal status combined two pieces of information: the duration of court-ordered treatment (one to six months or seven months or longer) and whether a given month occurred before, during, or after the court order was in effect. Comparisons could then be made between AOT recipients who had completed a longer or shorter court-ordered period of AOT, those who were currently under longer or shorter court orders, and those who had not received AOT (as a baseline reference). Start and end dates for court orders were obtained from OMH tracking information for the program. Use of intensive services was captured via monthly Medicaid service claims for assertive community treatment (ACT) or intensive case management. (We also evaluated the combination of ACT and intensive case management services as an outcome during the post-AOT period to address the question of whether former AOT recipients continue to receive intensive services after the court order ends.)

Five indicator variables were used for region. Outcomes for persons receiving services in the Central, Hudson River, Long Island, and Western regions of the state were compared with those for persons receiving services in the New York City region.

Race-ethnicity, sex, and age were all represented by indicator variables in the analysis. Hispanics, blacks or African Americans, Asians, and persons from other racial-ethnic backgrounds were compared with non-Hispanic whites. Males were compared with females, and individuals aged 43 and older (the median age) were compared with those younger than 43.

Diagnosis was obtained from Medicaid claims. Specifically, primary diagnoses on claims were grouped into four categories: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, and other. A hierarchical coding scheme was then used to count the number of claims with each diagnosis; the most frequent diagnosis type over the study period was then used.

Data structure

Analytic files based on Medicaid data were created that contained multiple observations per person. Our study period for the Medicaid data consisted of 88 months—November 1999 through February 2007. Utilizing these 88 months, we created a vertical data shell in which each individual had 88 rows of data. In this data structure, each month became a separate record and each type of service event or status, such as being on court-ordered treatment or not, became a separate variable. Each individual's Medicaid claims history was examined for receipt of any Medicaid-reimbursed mental health services (for example, ACT, inpatient admission, and pharmacy fills) that occurred in a given month during the study period. Separate variables for each type of service were created and populated with values from the individual's Medicaid-reimbursed services. Dates of each individual's court order were then merged with this file, which allowed us to evaluate the association between period—before, during, and after AOT—and a variety of outcomes using repeated-measures regression techniques.

Analysis

For all available time periods, we analyzed Medicaid-reimbursed mental health service encounter claims, comparing three periods of time for outpatient commitment: before initiation, while the court order was in effect, and after expiration of the order. This study focused on the time period after the expiration of the court order.

Specifically, we compared the mean frequency and variability of outpatient and inpatient services billed to Medicaid during these three periods to test the null hypothesis that parameters did not differ significantly within persons across these periods. Conceptually, this comparison over time treats each recipient as his or her own "control." We made appropriate statistical adjustments to account for the nonindependence of observations. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.1.

Results

Sample characteristics

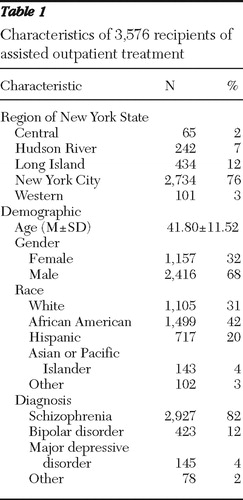

Table 1 shows a profile of the sample. More than three-quarters of the current and former AOT recipients (76%) were located in New York City. The second largest proportion was in Long Island (12%). The remaining three regions had substantially fewer recipients. (For a discussion of these regional differences, see the article by Robbins and colleagues [16] in this special section.) The mean age of recipients was 42 years, and two-thirds of the sample (68%) were male. Forty-two percent of AOT consumers were African American, just under one-third were white (31%), and 20% were Hispanic. Four-fifths of the sample (82%) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The next most prevalent diagnoses were bipolar disorder (12%), major depression (4%), and other (2%).

|

Multivariable models

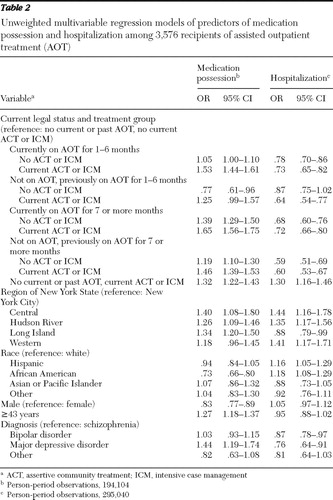

The results of multivariable analyses are shown in Tables 2 and 3 . Former AOT recipients who had a prior long-term court order—more than six months—were significantly more likely than those with no history of AOT, ACT, or intensive case management (comparison group) to possess medication for at least 80% of the days in any given month. This was the case whether or not the former AOT recipients were currently in receipt of intensive case coordination services (ACT or intensive case management). However, the effect was stronger when intensive services were in place for a given month than when they were not. In addition, former AOT recipients who had a prior short-term court order (six months or less) and who were not currently receiving intensive services were significantly less likely than the comparison group to possess medication at a high rate, although the effect did not reach statistical significance. Former AOT recipients with a prior short-term court order who were currently receiving intensive services were not significantly more likely than the comparison group to possess medication at a high rate, although the effect approached significance (p<.10).

|

|

For hospital admissions the findings were similar. Specifically, former AOT recipients who had prior short-term court orders but who were not currently receiving ACT or intensive case management services were no less likely to experience an inpatient admission than the comparison group (those with no current or past involuntary outpatient commitment or intensive services). However, former AOT recipients who had past court-ordered treatment of seven or more months and who were not currently receiving intensive services were significantly less likely than the comparison group to experience an inpatient admission in any given month. Former AOT recipients with both short- and long-term prior court orders who were currently receiving intensive services were significantly less likely than the comparison group to be hospitalized; the effect was slightly stronger for those who had a longer prior court order.

In both models in Table 2 , African-American recipients had worse outcomes than white recipients; that is, they were less likely to possess medication at a high rate and more likely to be admitted to the hospital. The same was true for AOT recipients of Hispanic ethnicity; however, the effect for reduced medication possession was not significant (p<.10). In addition, recipients with a major depressive disorder had better medication and hospitalization outcomes than those with schizophrenia. There were no significant differences between those with bipolar disorder and those with schizophrenia in medication possession outcomes; however, those with bipolar disorder were less likely to be hospitalized than those with schizophrenia.

We also constructed two stratified models, one specific to New York City and the other with data from all other regions. These additional analyses were undertaken to explore potential regional differences in post-AOT outcomes (see Robbins and colleagues' report [16] in this issue). For the New York City model, the post-AOT effects were identical to those presented in Table 2 . The strongest effects—both for improved medication possession and reduced hospitalization—were found for court orders lasting longer than six months. In the model for all other regions, two results differed from those in Table 2 . First, for former AOT recipients who had prior court orders of seven or more months, no significant effect was found for improved medication possession or reduced hospitalization for months in which they were not receiving intensive treatment. Finally, former AOT recipients in other regions who had prior court orders of six months or less and who were currently receiving intensive treatment did not have significantly reduced hospitalizations. All other findings for the regional model were similar to those presented in Table 2 .

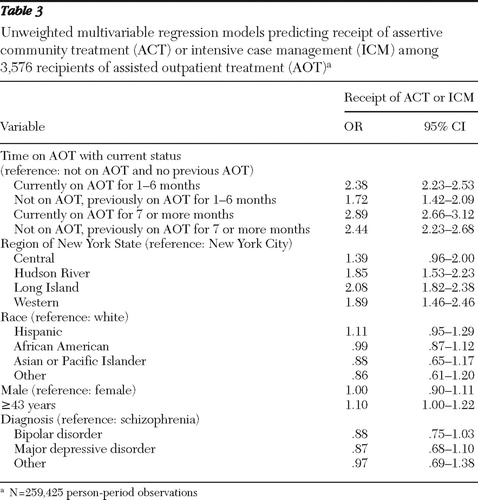

We also examined the relationship between post-AOT treatment status and the likelihood of continuing to receive intensive services ( Table 3 ). Current or prior receipt of AOT increased the likelihood of receiving intensive services compared with the pre-AOT period. Among current and former AOT recipients, those with long-term court orders were more likely than those with short-term court orders to receive intensive services in any given month.

Discussion

This study used data from New York's AOT program to examine whether selected gains made during outpatient commitment were sustained over time, continuing into the post-AOT period. We examined two main outcomes—possession of psychotropic medications and inpatient hospital admissions—and their associations with duration of outpatient commitment and receipt of intensive services.

We found that when court-ordered treatment ends, sustained improvements in medication possession and reductions in hospitalizations vary according to the length of time the recipient spent under the court order. Former AOT recipients who had short-term court orders (six months or less) possessed psychotropic medications at a high rate (for at least 80% of the days in a given month) and had fewer hospitalizations only when they continued to receive intensive case coordination services (ACT or intensive case management or both). However, former AOT recipients with long-term court-ordered treatment (seven or more months) had high rates of medication possession and fewer hospitalizations regardless of whether they continued to receive intensive services. Thus it appears that improvements are more likely to be sustained if court-ordered treatment continues for longer than six months. It is also important to note that those who had long-term court orders were more likely than those with short-term court orders to receive intensive services in any given month after the discontinuation of the court order.

This study had several limitations. The analysis did not control for the various reasons for receipt of longer or shorter periods of court-ordered treatment or for discontinuation of court-ordered treatment at a given time. We were able to control for some but not all theoretically relevant covariates. Also, hospitalization is a somewhat ambiguous outcome for evaluating involuntary outpatient commitment's effectiveness ( 23 ). For some individuals with serious mental illness, hospitalization represents a needed resource to which involuntary outpatient commitment may provide timely access. For others, hospitalization may indicate a failure of community-based treatment. In any event, reductions in hospital admissions do not necessarily correlate with improved quality of life ( 24 ). Also, from a methodological point of view, inpatient admissions may have shown a regression to the mean over time because of the typically high rate of admissions experienced by persons who eventually end up on involuntary outpatient commitment.

Finally, additional comment regarding our use of medication possession is warranted. First, it is important to note that our measure of possession is only an assessment of whether an individual had obtained adequate medication for a month. It does not capture whether the medication was taken. Next, although several studies have demonstrated that increased medication possession is associated with reduced hospitalization for patients with schizophrenia in Medicaid and Department of Veterans Affairs populations ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 ), it is important to consider that the patients in these study populations represented a mix of intensive and standard outpatient treatment settings and services. We are unaware of research that links improved medication possession with reduced hospitalization in populations that are predominantly served by intensive, enhanced services, in which providers often refill prescriptions (a refill does not mean patient adherence) and closely monitor clients for illness exacerbations (for example, providers are able to rapidly address nonadherence by encouraging the patient to adhere).

Involuntary outpatient commitment remains one of the most controversial issues in mental health law. There have been few data on outcomes associated with time periods after the court order ends ( 11 , 12 ). Data from the study reported here show that long-term involuntary outpatient commitment was more advantageous than short-term involuntary outpatient commitment. Because this was a retrospective study based on secondary data, we were unable to randomly assign participants and to test for specific causal mechanisms related to the improved outcomes found for those who had their original court order renewed beyond six months. However, future research should aim to test such potential mechanisms. For example, it is still unclear whether being placed on extended court-ordered treatment initiates a pattern of long-term participation in treatment. Our data lend some credibility to this assumption in that individuals with long-term orders were more likely than those with short-term orders to receive intensive services in any given month after the court order was lifted. However, these data also show that individuals experiencing long-term involuntary outpatient commitment were likely to maintain the benefits they experienced while under the court order, regardless of whether intensive services were delivered in any given month during the period after outpatient commitment. These results also indicate that persons who were under long-term court orders were not deterred from voluntarily seeking and receiving intensive services once the court order was lifted.

Conclusions

These findings are among the first evidence regarding outcomes in the period after involuntary outpatient commitment. Insofar as court-ordered treatment is designed to reduce repeat hospitalizations and maintain community-based tenure, these results show positive effects for New York's AOT program, particularly when outpatient commitment periods last more than six months.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study is funded by the New York State Office of Mental Health, with additional support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of numerous individuals in collecting, synthesizing, and reporting the data for this effort. At Policy Research Associates, they thank Henry J. Steadman, Ph.D., Karli J. Keator, B.A., Wendy Vogel, M.P.A., Roumen Vesselinov, Ph.D., Jody Zabel, Steven Hornsby, L.M.S.W., and Amy Thompson, M.S.W. They also acknowledge the extensive reviews and critical feedback provided by the MacArthur Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment, which served as an internal advisory group to the study. Although the findings of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors, they gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance of the New York State Office of Mental Health in completing the report, including Steve Huz, Ph.D., Chip Felton, M.S.W., Peter Lannon, Susan Shilling, J.D., L.C.S.W., Qingxian Chen, Michael F. Hogan, Ph.D., Bruce E. Feig, and Lloyd I. Sederer, M.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Estroff S, et al: Psychiatric impairment, social contact, and violent behavior: evidence from a study of outpatient-committed persons with severe mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33(suppl 1):S86–S94, 1998Google Scholar

2. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Borum, R, et al: Involuntary out-patient commitment and reduction of violent behaviour in persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:324–331, 2000Google Scholar

3. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen, EB, et al: Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment on subjective quality of life in persons with severe mental illness. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:473–491, 2003Google Scholar

4. Swartz MS, Hiday VA, Wagner HR, et al: Measuring coercion under involuntary outpatient commitment: initial findings from a randomized clinical trial; in Research in Community Mental Health: Coercion in Mental Health Services. Edited by Morrissey JP, Monahan J. Stamford, Conn, JAI, 1999Google Scholar

5. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: A randomized controlled trial of outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Google Scholar

6. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment and depot antipsychotics on treatment adherence in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:583–592, 2001Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Can involuntary outpatient commitment reduce hospital recidivism? Findings from a randomized trial with severely mentally ill individuals. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1968–1975, 1999Google Scholar

8. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al: The perceived coerciveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: findings from an experimental study. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 30:207–217, 2002Google Scholar

9. Rohland BM, Rohrer JE, Richards CC: The long-term effect of outpatient commitment on service use. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 27:383–394, 2000Google Scholar

10. Wagner HR, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Does involuntary outpatient commitment lead to more intensive treatment? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:145–158, 2003Google Scholar

11. Hiday VA, Scheid-Cook TL: A follow-up of chronic patients committed to outpatient treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:52–59, 1989Google Scholar

12. Van Putten RA, Santiago JM, Berren MR: Involuntary outpatient commitment in Arizona: a retrospective study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:953–958, 1988Google Scholar

13. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, George LK, et al: Interpreting the effectiveness of involuntary outpatient commitment: a conceptual model. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:5–16, 1997Google Scholar

14. Swartz MS: Introduction to the special section on assisted outpatient treatment in New York State. Psychiatric Services 61:967–969, 2010Google Scholar

15. Swartz MS, Wilder CM, Swanson JW, et al: Assessing outcomes for consumers in New York's assisted outpatient treatment program. Psychiatric Services 61:976–981, 2010Google Scholar

16. Robbins PC, Keator KJ, Steadman HJ, et al: Regional differences in New York's assisted outpatient treatment program. Psychiatric Services 61:970–975, 2010Google Scholar

17. Gilbert AR, Moser LL, Van Dorn RA, et al: Reductions in arrest under assisted outpatient treatment in New York. Psychiatric Services 61:996–999, 2010Google Scholar

18. Busch AB, Wilder CM, Van Dorn RA, et al: Changes in guideline-recommended medication possession after implementing Kendra's Law in New York. Psychiatric Services 61:1000–1005, 2010Google Scholar

19. Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, Swartz MS, et al: Robbing Peter to pay Paul: did New York State's outpatient commitment program crowd out voluntary service recipients? Psychiatric Services 61:988–995, 2010Google Scholar

20. Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al: Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:692–699, 2004Google Scholar

21. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639, 2002Google Scholar

22. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Google Scholar

23. O'Reilly RL: Does involuntary out-patient treatment work? Psychiatric Bulletin 25:371–374, 2001Google Scholar

24. Steadman HJ, Gounis K, Dennis D, et al: Assessing the New York City involuntary outpatient commitment pilot program. Psychiatric Services 52: 330–336, 2001Google Scholar

25. Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 55:886–891, 2004Google Scholar