Assisted Outpatient Treatment in New York: Regional Differences in New York's Assisted Outpatient Treatment Program

Involuntary outpatient commitment statutes permit courts to mandate persons with severe mental illness to comply with treatment in the community. Failure to adhere to the conditions of the court order can result in a range of consequences, including involuntary hospitalization. Although persons mandated by the court to community treatment represent a small proportion of the total adult mental health service population, this court-ordered population receives disproportionate attention given their serious needs, high cost to the service system, and the public's concern about the target population of these statutes. Forty-four states now permit some form of involuntary outpatient commitment, and because of the contentious debate surrounding this issue ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ), policy makers require more information about involuntary outpatient commitment.

Most research on involuntary outpatient commitment has focused on the impact of these court orders on outcomes such as treatment adherence ( 15 ), quality of life ( 16 ), hospital readmissions ( 17 , 18 ), violence and victimization ( 19 ), and arrests ( 19 ). With the exception of one study that touched on statewide variations in the administration of involuntary outpatient commitment ( 20 ), missing from these studies is a thorough examination of the way in which these laws have been implemented, the systemic impact of these programs, and how, in practice, involuntary outpatient commitment is used.

In 1999 the New York State legislature enacted "Kendra's Law," establishing a provision for assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) for adults with mental illness at risk of not living safely in the community. Originally enacted for a five-year period, the AOT statute was extended for an additional five years in 2005. Included in this extension was a legislatively mandated and funded, independent evaluation of AOT. The main objective of this evaluation was to provide the state legislature with data to inform the review of this legislation in 2010.

In this article, we describe the implementation of AOT in New York State, focusing specifically on differences in implementation and administration of the AOT program by county and region and how these differences emerged within the same statutory guidelines. Specifically, we examined the following questions: Are criteria for Kendra's Law applied differently across the state? Do programs vary widely in referrals, recommendations to the court, resources to apply the law, or other factors? What is the level of uniformity in the implementation of a statewide law when the unit of government responsible for its implementation is ultimately the county?

Methods

Data used for the program implementation analyses were obtained from three sources: key informant interviews, administrative and program evaluation data, and official history data for a sample of AOT clients. This project was approved by the institutional review boards at Duke University, Policy Research Associates, New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), and Biomedical Research Alliance of New York.

Between February 2007 and April 2008, we conducted 50 key informant interviews with persons knowledgeable about the AOT program throughout New York State. A snowball methodology was used: AOT county coordinators were interviewed and then asked to identify other persons knowledgeable about the AOT program. Key informants included AOT coordinators, county directors of community services, judges, attorneys from New York's Mental Hygiene Legal Service (MHLS), psychiatrists, treatment providers, peer advocates, family members, and other referred parties. Key informants were selected primarily from the six counties that also participated in an in-depth client interview study—Albany, Erie, Monroe, Nassau, New York, and Queens. However, additional interviews were conducted with respondents from other counties and with regional and statewide representatives.

The focus of the interviews was on program operations. The objective was to provide a greater understanding of how AOT works throughout New York State. Areas of inquiry included questions regarding the general AOT process and operations, local interpretations of AOT, strengths and weaknesses of the program, comparisons of AOT court-ordered clients with others receiving voluntary enhanced services, and how the program interfaces with other service and housing programs. Respondents provided verbal consent and did not receive any remuneration for their participation in this interview.

We obtained AOT program administrative and evaluation databases, specifically Tracking for AOT Cases and Treatments and the AOT evaluation database. The U.S. Census Bureau's online database was used to provide estimates of county populations ( 21 ). County estimates of the prevalence of severe mental illness were obtained by applying epidemiological survey data to the demographic profile of each county ( 22 , 23 ). Analyses of these data were conducted for AOT recipients spanning a period of nine years after the implementation of AOT.

Client history data were collected for a sample of individuals from the six study counties. Local AOT coordinators provided the names. We enrolled a sample of 211 unique individuals from current AOT rosters as well as clients receiving similar services who were not court ordered. These individuals' official records were accessed in order to gather histories, specifically AOT and voluntary services data.

Results

Implementation of the AOT program

Under Kendra's Law, a local AOT program was to be created in order to oversee AOT implementation in each county and New York City. We found some counties had a formal AOT program that had never been used. These counties often used their local Single Point of Access program to coordinate services for high-need populations. We also found some counties had no formal AOT program. Common reasons cited for not utilizing AOT included lack of program infrastructure to support court orders, the belief that mental health problems should not be dealt with by the legal system, and the position that court orders are for the benefit of providers (for example, as a risk management strategy) rather than clients.

All counties receive AOT program service dollars, regardless of program status or utilization. Counties without active AOT cases may use these funds to serve high-need clients in other ways. Interviews with county officials indicated that AOT service dollars are very important to the local service system, although no specific information about how these program dollars were spent was obtained in this study.

Trends in the application of AOT

As Figure 1 shows, after AOT program implementation in 1999 the number of AOT investigations remained much higher than the number of resulting petitions and court orders. Investigations began to decline after 2001 as program administrators were able to improve identification and referral of eligible AOT candidates. Investigations that concluded with a petition to the court and hearing were likely to result in an AOT court order. Of the 9,307 AOT hearings held between 1999 and 2007, a total of 8,752 (94%) resulted in a court order.

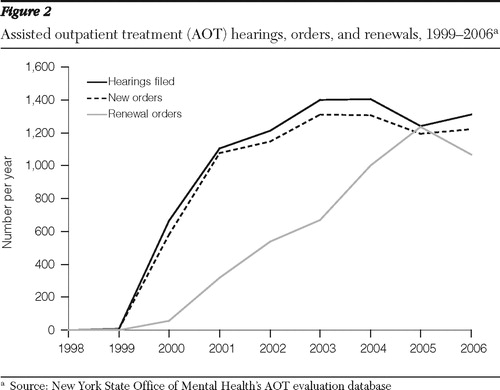

Figure 2 shows a steep upward curve in AOT hearings, orders, and renewals from 1999 to 2003. After 2003 the volume of AOT cases leveled off as counties refined policies and procedures. Also, as more people were placed on AOT, the remaining pool of eligible individuals shrank. From program inception through 2007, a total of 8,752 initial AOT orders and 5,684 renewals were granted. Figure 3 displays the cumulative number of AOT orders by county as of 2005, with counties shaded to indicate the estimated absolute size of the population with serious mental illness ( 22 , 23 ). AOT orders have tended to concentrate in New York City and several upstate metropolitan areas, which also have larger base populations with serious mental illness. Likewise, there was a higher density of AOT recipients in these counties. However, in some counties the number of AOT orders was not consistent with the population density of individuals with serious mental illness, which suggests other sources of variation.

Many county program personnel we interviewed indicated that their AOT program had reached capacity. This was in part because the volume of AOT orders and renewals is inevitably affected by local service capacity. For example, many AOT treatment plans specify assertive community treatment as the appropriate service modality for the AOT recipient. However, counties may have no available caseload openings on existing teams, often because scarce resources are already selectively used for individuals with the highest need, usually defined as those at risk of violent behavior.

AOT program variations

For AOT to be ordered by the court, the petitioner for AOT must establish that legal eligibility criteria are met, including that AOT is the least restrictive alternative. For some individuals, an alternative plan may be drafted in which the individual agrees to receive enhanced voluntary services (EVS). In most cases this includes assignment to intensive case management or assertive community treatment. Although voluntary, this EVS agreement may have conditions of treatment participation designed to avoid a court order for AOT.

The process for initiating EVS agreements and drafting enhanced service plans are not statutory elements of Kendra's Law. However, they are used by many local AOT programs either before initiation of AOT or after some period of AOT. Some counties have instituted formal procedures for EVS agreements (that is, legal documents), whereas other counties use less formal written or verbal agreements. Counties do not report individual or identifying data to OMH for persons who are served under these agreements. However, aggregate data on the annual number of EVS agreements have been included in earlier program reports.

The extent to which EVS agreements are used and the timing of these agreements varied across counties. Some AOT programs sought the court mandate before moving toward an agreement (that is, AOT First). After some success under the mandate, EVS agreements were used as a path out of AOT. Other AOT programs first invited participation in EVS before resorting to the court mandate. These county programs sought a court order only if the individual did not comply with the treatment specified in the EVS agreement (that is, EVS First).

We found notable regional differences in the use of these two distinct models of AOT. Figure 4 shows the differences between upstate programs (Albany, Erie, and Monroe) and downstate programs (Nassau, New York, and Queens) by sample. These data were drawn from client databases in the six counties—98 AOT active clients and 93 EVS active clients. We found that EVS First was primarily used in upstate counties and was thought to satisfy the least restrictive alternative requirement (inpatient psychiatric hospitalization being the most restrictive). Counties that utilized the AOT First model, predominantly downstate where court orders were often given before discharge from an inpatient facility, also cited the least restrictive clause as the impetus for this model. The court order was argued to be the least restrictive alternative to the inpatient setting. Liability concerns were generally cited as the rationale for the AOT First model; that is, hospitals are more comfortable discharging a patient with an AOT court order. Limited service slots and housing availability were also cited as influential in the decision to use this model because court-ordered individuals are given priority access to scarce resources.

Regional variations in the AOT program

We found other notable regional differences in AOT program implementation, including the length of time an individual remained on a court order and the source of the petition. The majority of court orders (65%) were renewed beyond the initial six-month period; however, only a small minority of persons who completed AOT (17%) remained under a court order for more than 30 months. Regions varied to some extent in the duration of court orders. For example, nearly half of court orders (48%) were terminated after the initial six-month period in the Central Region, whereas eight in ten court orders (81%) were renewed at least once beyond the initial six months in Long Island.

One important difference between AOT and EVS agreements was that EVS agreements were rarely renewed. It was very unlikely, particularly downstate, for an individual to remain on a voluntary agreement for longer than six months. In the AOT First model, EVS agreements were often used as a transition from AOT. Under the EVS agreement, individuals maintain the same service level for six months after AOT. They may then exit the formal AOT program, although case management and other services may continue as needed.

Another regional variation can be found in the source of the AOT petition ( Figure 5 ). The vast majority (84%) of petitions were filed while the subject of the petition was an inpatient at a psychiatric hospital. A small proportion (13%) were filed while the individual was in the community, and even fewer (3%) were filed by correctional facilities. Interviews with key informants provided several factors that may explain some of these variations.

Important factors cited were regional differences in rates of involuntary hospitalization and incarceration attributable to bed capacity and the location of facilities in large metropolitan areas. In some regions a greater proportion of the AOT target population may be hospitalized and thus more accessible to the AOT initiation process. Second, doctors in some facilities used AOT more routinely as part of a discharge plan and as a form of risk management. Third, the cost of petitioning for AOT can be prohibitive for smaller hospitals or individuals. Family members may not wish to initiate the petition, fearing that it will disrupt their relationship with their loved one, and prefer instead to wait until a petition results from a hospitalization. Finally, petitions from jail can be problematic given the uncertainty of inmate release times.

Administrative and procedural variations

We also found variations in the administration of the AOT program. Some counties integrated AOT with their Single Point of Access program to facilitate the process and provide highly coordinated services. Other counties established formal administrative procedures, including standardized forms and reporting policies, to expedite administration of the law. For example, the New York City boroughs reported a formal removal procedure and pick-up team when individuals are noncompliant with the court order. A removal order is a physician-directed order for an individual who is noncompliant with treatment to be temporarily removed from the community to a hospital for the purpose of an examination to determine whether hospitalization is required.

Other variations in AOT program implementation stemmed from the court proceedings themselves. Counties varied in whether they had an appointed judge presiding over AOT hearings or whether this position was rotated among several judges. In some counties the client for whom the AOT petition is initiated can stipulate to the terms of the petition in order to avoid a court hearing. The belief is that forcing clients to attend a court hearing for AOT when they agree to the terms is not a client-centered approach and can damage the relationship between client and provider. In this same vein, some counties reported that they do not require the treating psychiatrist to testify if the petition is uncontested.

Although the statute guarantees the right to counsel for individuals at all stages of the proceedings, the exact role of the attorney is left open to interpretation. Regional differences exist in the attitude of MHLS attorneys to the AOT program. In some counties, the attorneys viewed AOT as the least restrictive alternative to hospitalization and as a gateway to receipt of needed community services. Information provided in interviews indicated that these attorneys are likely to foster a collaborative—and whenever possible—a nonadversarial relationship with the AOT program staff and to work together to utilize AOT as a tool to obtain early discharge for patients ( 24 ). One MHLS attorney clearly expressed this viewpoint: "We see AOT as a way for some clients to get what they need. They are severely mentally ill and need good follow-up treatment in the community. This is a way for them to get out of the hospital much sooner."

In other MHLS departments, attorneys viewed their legal role as adversarial with respect to the AOT petitioners, representing their client's own wishes rather than the client's "best interest" per se, as defined by clinicians or family members. A judge in one region where MHLS attorneys were known to hold this view noted that this advocacy on the part of the attorney was a major strength of the program.

Discussion

AOT court orders in New York State rapidly increased from the program's inception to 2006 but have leveled off in recent years. This trend may be attributable to limited capacity of local AOT programs and lack of an increase in program funding. Across the state the highest number of AOT orders tended to be found in areas with a greater concentration of adults with severe mental illness. Over the first decade of AOT, significant regional differences across several elements of AOT implementation and administration have evolved. Upstate New York counties reported frequent use of an EVS First model before resorting to a court mandate. Downstate New York programs reported use of AOT First almost exclusively, using EVS agreements as a transition from AOT.

Implementation and operation of the AOT program were found to vary considerably across New York State. Although the criteria for AOT are clear, the procedures and program administration varied greatly across counties. Each county is its own decision maker, and the structure of the program was found to reflect the views of the director of community services and the configuration of local mental health services. Some consistency was found across the boroughs of New York City, because the AOT program is highly coordinated with a central authority.

Conclusions

Some adaptations of AOT may not conform to the letter of the law but instead are an outgrowth of local interpretations of the law. The key finding of the two models presented in this article—AOT First and EVS First—is an example of such an adaptation. Other adaptations include whether the client or psychiatrist is required to be present in cases in which the client has stipulated to the order. These local adaptations were made in the absence of formal guidance (in the form of policies and procedures) from a central source. Policy makers may want to consider whether changes to the law should be made in order to allow for local interpretations or to address whether uniformity of the AOT program is the goal. These considerations should be made in the context of improving recovery and service delivery—that is, how can the AOT program be used to support recovery of people with mental illness?

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study is funded by the New York State Office of Mental Health, with additional support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of numerous individuals in collecting, synthesizing, and reporting the data for this effort. Richard Van Dorn, Ph.D., Department of Mental Health Law and Policy, University of South Florida, assisted greatly with data management and analysis. At the Services Effectiveness Research Program, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, the authors acknowledge the considerable efforts of Lorna L. Moser, Ph.D., and Allison R. Gilbert, Ph.D., M.P.H. At Policy Research Associates, they thank Wendy Vogel, M.P.A., Roumen Vesselinov, Ph.D., Jody Zabel, Steven Hornsby, L.M.S.W., and Amy Thompson, M.S.W. They also acknowledge the extensive reviews and critical feedback provided by the MacArthur Research Network on Mandated Community Treatment, which served as an internal advisory group to the study. Although the findings of the study are solely the responsibility of the authors, they gratefully acknowledge the support and assistance of the New York State Office of Mental Health in completing the report, including Steve Huz, Ph.D., Chip Felton, M.S.W., Peter Lannon, Susan Shilling, J.D., L.C.S.W., Qingxian Chen, Michael F. Hogan, Ph.D., Bruce E. Feig, and Lloyd I. Sederer, M.D.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Allen M, Smith VF: Opening Pandora's box: the practical and legal dangers of involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:342–346, 2001Google Scholar

2. Appelbaum P: Thinking carefully about outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:347–350, 2001Google Scholar

3. Cornwell JK, Denney R: Exposing the myths surrounding preventive outpatient commitment for individuals with chronic mental illness. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:209–232, 2003Google Scholar

4. Geller JL: The evolution of outpatient commitment in the USA: from conundrum to quagmire. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 29:234–248, 2006Google Scholar

5. Geller JL, Fisher WH, Grudzinskas AJ, et al: Involuntary outpatient treatment as "deinstitutionalized coercion": the net-widening concerns. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 29:551–562, 2006Google Scholar

6. Monahan J, Swartz M, Bonnie RJ: Mandated treatment in the community for people with mental disorders. Health Affairs 22(5):28–38, 2003Google Scholar

7. Mulvey EP, Geller JL, Roth LH: The promise and peril of involuntary outpatient commitment. American Psychologist 42:571–584, 1987Google Scholar

8. O'Reilly R: Why are community treatment orders controversial? Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 49:579–584, 2004Google Scholar

9. Perlin ML: Therapeutic jurisprudence and outpatient commitment law: Kendra's Law as case study. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:183–208, 2003Google Scholar

10. Petrila J, Ridgely MS, Borum R: Debating outpatient commitment: controversy, trends, and empirical data. Crime and Delinquency 49:157–172, 2003Google Scholar

11. Saks ER: Involuntary outpatient commitment. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:94–106, 2003Google Scholar

12. Schopp RF: Outpatient civil commitment: a dangerous charade or a component of a comprehensive institution of civil commitment? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:33–69, 2003Google Scholar

13. Wales HW, Hiday VA: PLC or TLC: is outpatient commitment the/an answer? International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 29:451–468, 2006Google Scholar

14. Winick BJ: Outpatient commitment: a therapeutic jurisprudence analysis. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law 9:107–144, 2003Google Scholar

15. Rain SD, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC: Perceived coercion and treatment adherence in an outpatient commitment program. Psychiatric Services 54:399–401, 2003Google Scholar

16. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Effects of involuntary outpatient commitment on subjective quality of life in persons with severe mental illness. Behavioral Sciences and the law 21:473–491, 2003Google Scholar

17. Burgess P, Bindman J, Lesse M, et al: Do community treatment orders for mental illness reduce readmission to hospital? An epidemiological study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41:574–579, 2006Google Scholar

18. Frank DF, Perry JC, Kean D, et al: Effects of compulsory treatment orders on time to hospital readmission. Psychiatric Services 56:867–869, 2005Google Scholar

19. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: A randomized controlled trial of involuntary outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Google Scholar

20. Christy A, Petrila J, McCranie M, et al: Involuntary outpatient commitment in Florida: case information and provider experience and opinions. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 8:122–130, 2009Google Scholar

21. Population Estimates. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2009. Available at www.census.gov/popest/estimes.php Google Scholar

22. Holzer III C, Kabel J, Kohlenberg E, et al: The Prevalence Estimation of Mental Illness and Need for Services Study Technical Report. Olympia, Wash, Department of Social and Health Services, Division of Mental Health and Research and Data Analysis Division, 1999Google Scholar

23. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, et al: The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:60–82, 2004Google Scholar

24. Swanson J: What would Mary Douglas do? A commentary on Kahan et al, "Cultural cognition and public policy: the case of outpatient commitment laws." Law and Human Behavior 34:176–185, 2009. Available at DOI 10.1007/s10979-009-9184-xGoogle Scholar