Antidepressants and Suicide Risk: How Did Specific Information in FDA Safety Warnings Affect Treatment Patterns?

From June 2003 to October 2004, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released five separate safety warnings related to antidepressant use and the increased risk of suicidality among children. These FDA actions elicited controversy that reflected the fundamental trade-offs associated with weighing risks and benefits under conditions of scientific uncertainty.

Supporters of the FDA's actions argued that the evidence of elevated risks of suicidality linked to use of antidepressants by youths was sufficiently serious to warrant informing providers and consumers. Critics countered that such action would significantly reduce the use of an effective treatment for depression ( 1 ), thereby producing poorer mental health outcomes (including possibly increased risk of suicide) in an underserved population ( 2 ). By 2005, researchers documented 20%–30% declines in antidepressant use by children and adolescents ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ), and there has been a concurrent increase in the national adolescent suicide rate, although no causal association has been documented ( 9 ).

Yet little is known about whether specific safety information conveyed through these FDA warnings was associated with changes in treatment patterns. This study differed from prior work in that it examined changes in treatment patterns in the periods after each individual warning to determine whether specific information contained in these warnings was associated with relevant treatment changes. Understanding how inclusion of specific health information in FDA warnings affects treatment patterns is important because adherence to these safety recommendations could alter the risk-benefit profile of pediatric antidepressant use.

We examined three research questions related to whether specific information contained in FDA safety warnings translated into changes in treatment patterns for children treated for major depressive disorder. First, did the use of paroxetine (either the generic product or the branded Paxil) decline after possible risks of treating children with it were disclosed in an FDA warning? Second, did the use of fluoxetine (either the generic product or the branded Prozac) increase after specific benefits in treating children with it were mentioned in FDA warnings? Third, after the FDA recommended increased monitoring, were children with major depression who received prescriptions for antidepressants more likely to have two or more outpatient visits in the first 30 days after initial drug treatment?

FDA's public releases about antidepressant use and suicidality

Over an 18-month investigation of pediatric use of antidepressants, the FDA issued five separate safety warnings. The content of these public releases shifted as new information surfaced during the investigation.

The initial safety warning was released on June 19, 2003, shortly after the initial disclosure by GlaxoSmithKline of clinical trial evidence of increased risk of suicidality among pediatric patients. This statement focused exclusively on the risks associated with pediatric use of Paxil or generic paroxetine, recommending that it "not be used in children under the age of 18 for the treatment of major depressive disorder." In this one-page statement, the FDA noted that "three well-controlled trials in pediatric patients with MDD failed to show that the drug was more effective than placebo." The statement emphasized that there was "no evidence that Paxil is effective in children or adolescents with major depressive disorder" and that paroxetine was "not currently approved for use in children and adolescents." No risks associated with other medications in the antidepressant class were mentioned.

With its second public release—a health advisory issued on October 27, 2003, and directed at physicians and other health professionals—the scope of the FDA's recommendations changed. The agency alerted clinicians to reports of "suicidality (both suicidal ideation and suicide attempts) in clinical trials of various antidepressant drugs in pediatric patients with major depressive disorder." The agency noted that it had completed a preliminary review of evidence on eight antidepressants and determined that additional data and analysis were needed. The FDA stated that the data did not clearly establish an association between the pediatric use of antidepressants and increased suicidal thoughts or actions but that it was "not possible at this point to rule out an increased risk of these adverse events in any of these drugs." The October 2003 warning included two new pieces of information. First, the agency reported that of the drugs evaluated only fluoxetine showed effectiveness in treating major depressive disorder among children. Second, the advisory noted that "close supervision of high-risk patients should accompany initial drug therapy."

On March 22, 2004, the FDA issued a third public release. This advisory expanded the focus to ten antidepressants and required pharmaceutical manufacturers to include a warning statement on their product labels. Like the October 2003 warning, this advisory included information on the efficacy of fluoxetine in treating children and more explicitly emphasized the importance of monitoring.

The fourth public statement was released by the FDA on September 16, 2004, directly after a meeting of the FDA's Psychopharmacological Drugs and Pediatric Advisory Committees. The committees were presented results from an FDA-sponsored meta-analysis of clinical trial data, which found that the rate of suicidality among children assigned to receive selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) was twice that of the group that received a placebo. This evidence led to a 15-to-8 decision by committee members to recommend a black-box warning related to increased risk of suicidality among pediatric patients for all antidepressant drugs. The FDA's September 16 statement noted that the agency had begun "working expeditiously to adopt new labeling to enhance warnings associated with use of antidepressants."

On October 15, 2004, the FDA issued a fifth public release on pediatric use of antidepressants. This public health advisory directed manufacturers of all antidepressants to revise product labeling to include a black-box warning on the increased risk of suicidality among children and adolescents. This warning applied to 36 drugs, including SSRI-class drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. The advisory included recommendations related to the frequency of psychotherapy and medication management visits. The labeling change request explicitly stated, for the first time, that "ideally, such observation would include at least weekly face-to-face contact with patients or their family members or caregivers during the first four weeks of treatment."

Evidence on the consequences of FDA actions

Several studies have examined changes in U.S. pediatric antidepressant prescribing rates in response to evidence of suicidality risk. Considering national pharmacy data, two early analyses found 20%–22% declines in antidepressant use among children and adolescents in 2004, before the issuance of the black-box warning ( 6 , 7 ). These first two analyses were not published in the peer-reviewed literature but were conducted by news organizations and published in the lay press.

In the peer-reviewed literature, Gibbons and colleagues ( 8 ) examined yearly SSRI prescription rates for children up to age 14 and found that overall SSRI use declined approximately 20% from 2003 to 2005, whereas new SSRI prescriptions declined 30% over this same period. Libby and colleagues ( 3 ), using outpatient and prescription drug claims, analyzed treatment episodes for depression and found that rates of newly diagnosed episodes of pediatric depression declined sharply. Considering the October 2003 FDA advisory as the policy action of interest, this study concluded that there was a 58% drop in use of SSRIs among children diagnosed as having depression from the level to be expected if prescribing trends begun before this controversy had continued; the drop in SSRI usage among adults was smaller (33%) ( 3 , 10 ). The investigators found no increase in use of psychotherapy or provider contact in the first three months of treatment ( 11 ). Finally, another study carefully considered the timing of the decline in antidepressant use and concluded that the decline began in February 2004 but leveled off by July 2004, with no further changes in prescribing patterns ( 4 ). Although these studies suggest that FDA actions led to substantial declines in pediatric antidepressant use, less information is available on whether specific recommendations conveyed in FDA safety warnings were associated with changes in treatment patterns.

Methods

Thomson Reuters' MarketScan database (2001–2005), which contains claims information for a national sample of more than 2.6 million enrollees, was used to conduct this analysis. Using outpatient claims, we identified all children (aged five to 17) with a diagnosis of major depression from May 2001 to November 2005. To classify major depressive disorder diagnoses, we used ICD-9 codes 300.4 (neurotic depression), 296.2 (major depressive disorder, single episode), 296.3 (major depressive disorder, recurrent episode), and 311 (depression not otherwise specified). For these children, all outpatient drug prescriptions for antidepressants were considered.

We used dates on claims and followed prior research ( 12 , 13 , 14 ) in constructing treatment episodes. We defined an episode of depression as new if a diagnosis was preceded by a period of at least 120 days of no treatment or diagnosis. The start date of the episode was the date the major depressive disorder was diagnosed. We considered care received within the first 30 days of initial diagnosis (for drug treatments) or 30 days of initiating drug treatment (for monitoring). To ensure that we observed the full washout period, episodes begun in the first 120 days of 2001 were omitted. We excluded episodes that began in the last 60 days of 2005 (the last year of our data) to ensure that we examined all services associated with treatment initiation, including 30 days after the initiation of drug treatment. We examined monitoring only when the drug was prescribed within the first 30 days of an episode.

Approximately 8% of individuals experienced more than one episode of care. We included all episodes in analyses out of concern that omitting later episodes would bias results and adjusted our standard errors to account for the lack of independence between repeat episodes. We also excluded individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder over the period studied. Using this algorithm, we identified 22,689 new episodes of treatment.

Outcome variables

We created four indicator variables to note whether the treatment episode included the following: any antidepressant drug use within 30 days of diagnosis; a paroxetine prescription, conditional on treatment with any antidepressant within 30 days of diagnosis; a fluoxetine prescription, conditional on treatment with any antidepressant within 30 days of diagnosis; and at least two outpatient visits within 30 days of initial drug treatment, conditional on treatment with an antidepressant within 30 days of diagnosis. To determine receipt of specific drugs, we relied on National Drug Codes noted on pharmacy claims. For outpatient visits, we considered all Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes related to either outpatient visits or medication management, because monitoring could occur in either type of visit (CPT codes 90801, 90802, 90804–90815, and 90862). To ensure that the outpatient visit was related to the mental health diagnosis, only visit records that noted mental health diagnoses were considered. In a robustness check, we identified additional evaluation and management visits that may have occurred in primary care (CPT codes 99201–99205; 99211–99215) and did not require a mental health diagnosis for these visits.

Statistical methods

We ran logistic regressions, including dummy variables for five distinct time periods: before the first FDA action on use of the antidepressant paroxetine for pediatric patients (May 1, 2001, through June 18, 2003), the period between the release of the first and second FDA safety warnings (June 19, 2003, through October 26, 2003), the period between the second and third FDA safety warnings (October 27, 2003, though March 21, 2004), the period between the third FDA safety warning and the FDA Advisory Committee meeting (March 22, 2004, through September 13, 2004), and the period after the FDA Advisory Committee meeting (September 14, 2004, through October 31, 2005). We did not consider the announcement of the black-box warning in October 2004 as a separate period, because it was issued very close to the date of the FDA advisory, which was issued in September 2004. We categorized episodes by the initial date of diagnosis. We also controlled for age, gender, and four geographic regions. For the "any antidepressant drug" outcome, we also controlled for season in which the episode began.

We used regression analyses to determine the adjusted probability estimates of each outcome during each period. To determine the effects on the original scale, we used the method of recycled predictions, calculating the adjusted probability of the relevant outcome for each individual in our sample and assuming that the individual was treated in each of our relevant time periods ( 15 ). For each period, we tested whether there was a significant change in prescribing or treatment from the preceding period by testing the equality of coefficients using a Wald test. This research was exempt from review by institutional review board because of the Code of Federal Regulations exemption specified in 45 CFR 46.101(b)(4).

Results

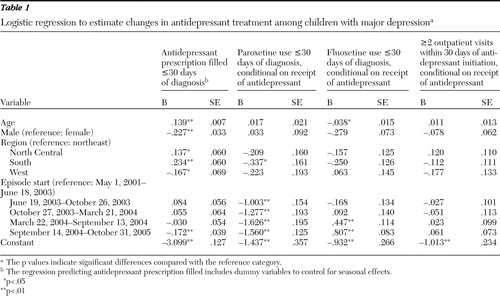

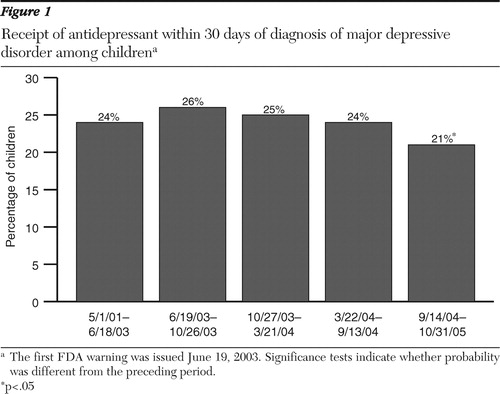

Table 1 indicates full regression results for all studied outcomes. We found a significant decline in use of antidepressant drugs after the September 2004 committee meeting ( Figure 1 ). For children with major depression, antidepressant use peaked beginning in June 2003, and we observed a 19% decline from this peak (26% versus 21%). This decline is in the range found in other studies.

|

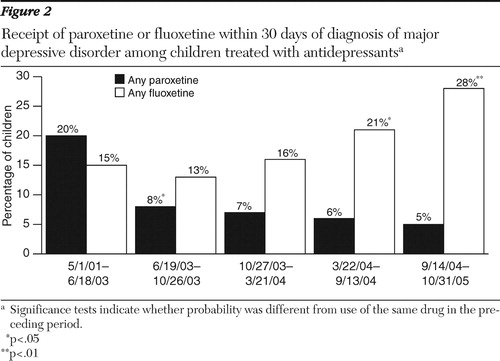

We next examined receipt of paroxetine. Because the first FDA safety warning noted a suicide risk associated only with use of paroxetine (and not other antidepressants), we expected providers to be more likely to choose an antidepressant other than paroxetine for children newly diagnosed as having major depression after this warning was issued. In the period after this first warning, paroxetine use declined dramatically, from 20% to 8% (p<.01) ( Figure 2 ). Rates of paroxetine use then remained low, although approximately 5% of new episodes of childhood depression were treated with paroxetine through 2005.

Next, we examined changes in the proportion of children who received fluoxetine. Conditional on treatment with an antidepressant, use of fluoxetine increased after the October 2003 warning, which first noted the benefits of fluoxetine, from 13% to 16%, although this change was not statistically significant ( Figure 2 ). The use of fluoxetine continued to increase, with a statistically significant increase to 21% of episodes treated with fluoxetine in the following period and to 28% of children being treated with fluoxetine by the last period studied.

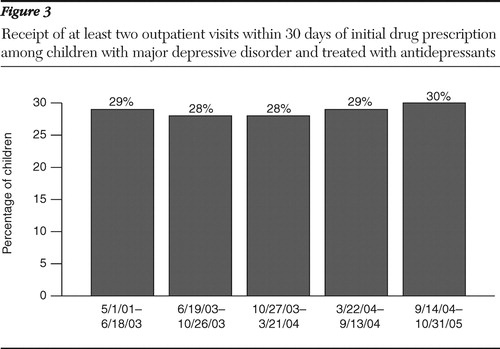

Finally, we found no significant change in the use of monitoring as a result of filling a prescription for an antidepressant ( Figure 3 ). Because some monitoring may occur in primary care, we used evaluation and management CPT codes to identify additional opportunities for monitoring. This outcome measure also indicated no significant change in the frequency of monitoring.

Discussion

Consistent with prior research, our findings showed significant declines in use of antidepressants. We found a substantial decline in the use of paroxetine and an increase in the use of fluoxetine during periods consistent with the release of information by the FDA on the dangers of paroxetine (June 2003) and on the benefits of fluoxetine (October 2003). Using pharmacy data, Olfson and colleagues ( 5 ) identified declines in prescribing rates for paroxetine in June 2003; however, it was not clear from pharmacy data how these declines translated into changing treatment patterns. Our results suggest that treatment initiation with paroxetine for children newly diagnosed as having major depressive disorder was relatively rare after the initial information about its risks was conveyed in the June 2003 FDA warning. We found that the total decline in overall antidepressant use was greater than the increase in fluoxetine use, indicating that providers were not simply switching from other antidepressants to fluoxetine. This finding suggests that at least in some cases, providers did not believe that the proven benefits of fluoxetine treatment outweighed the potential risks of pediatric SSRI use. We found that the FDA warnings encouraging increased use of monitoring when prescribing antidepressants had no effect.

There are several important implications of this research. First, the FDA was widely criticized for making the decision to issue a black-box warning for pediatric antidepressant use. Yet the black-box warning may not have been the primary factor contributing to the observed changes in treatment patterns. Confirming earlier studies, we found that the decline in antidepressant use began before the announcement of the black-box warning. It is difficult to know whether pediatric antidepressant use would have rebounded if the FDA had not issued this black-box warning, but there is no evidence to suggest that this would have occurred.

Second, we found that both risk and benefit information provided by the FDA led to changes in treatment patterns. There was concern that only potential risks would be communicated because of media reporting that emphasized risks rather than benefits ( 16 ). However, we found that physicians increased their use of fluoxetine, the only SSRI approved for pediatric use during this period. This increase in fluoxetine use was gradual and not significant until March 2004, approximately five months after the proven benefit of fluoxetine was noted in FDA warnings. It is interesting that the strong evidence base for the efficacy of fluoxetine in treating children had been previously available but did not lead to high rates of use until this evidence was highlighted by the FDA.

Third, although we found changes in prescribing patterns, the FDA's recommendation regarding increased physician monitoring appears to have been largely ignored. This may be due to the relatively high cost of office visits, a shortage of providers (particularly child psychiatrists), or the high out-of-pocket costs associated with mental health visits in many health plans. This finding highlights the limited powers of the FDA to directly affect the care received by patients. The FDA is "responsible for protecting the public health by assuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs." Yet, the agency possesses few direct methods for addressing safety risks beyond regulating specific marketing practices, such as requiring manufacturers to include warning labels on products and, in extreme situations, pulling products from the market. In the case of pediatric antidepressant use, providers appear to have heeded some FDA health and safety recommendations while ignoring others.

A number of limitations of this study are worth noting. First, we have no information on the compensatory use of psychosocial therapies not covered by patients' health plans (such as school counselors and clergy). Also important, we have information only on privately insured individuals, and results may have differed with a publicly insured population. Finally, because we did not consider a control group (because no appropriate control group was available), changes may be due, in part, to secular changes in treatment patterns that would have occurred in the absence of any FDA warnings. Young adults are not an appropriate control group, because we expect there to be spillover effects of the FDA warnings to young adults, even though they were not included in the original warnings ( 10 ).

Conclusions

Reductions in pediatric antidepressant use raise important public health concerns. In the 1980s and 1990s, the introduction of SSRI-class antidepressants led to a substantial increase in depression treatment among children and adolescents ( 17 , 18 , 19 ). Because depression is an undertreated disease ( 20 ) with the potential for long-term negative consequences, these increases were viewed at the time by many as important reductions in unmet need. Our findings suggest that the FDA plays an important role in communicating information to the public and providers and that FDA actions (via public statements and public health advisories) were associated with significant changes in practice patterns. Yet this role can be fraught with challenges in the context of an issue such as this one, which involves substantial scientific uncertainty. And, as our findings indicate, the FDA's ability to directly protect the public's health is limited in many cases, and treatment choice relies on physician judgment in weighing risks and benefits.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors acknowledge funding received through grant R01-MH080883 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Rosenheck has received research support from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study Team: Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. JAMA292:807–820, 2004Google Scholar

2. Brent DA: Antidepressants and pediatric depression: the risk of doing nothing. New England Journal of Medicine 351: 1598–1599, 2004Google Scholar

3. Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, et al: Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:884–891, 2007Google Scholar

4. Nemeroff CB, Kalali A, Keller MB, et al: Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:466–472, 2007Google Scholar

5. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss BG: Effects of Food and Drug Administration warnings on antidepressant use in a national sample. Archives of General Psychiatry 65:94–101, 2008Google Scholar

6. Rosack J: New data show declines in antidepressant prescribing. Psychiatric News, Sept 2, 2005, p 1Google Scholar

7. Harris G: Study finds less youth antidepressant use. New York Times, Sept 21, 2004Google Scholar

8. Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, et al: Early evidence on the effects of regulators' suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1356–1363, 2007Google Scholar

9. Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH:Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996–2005. JAMA 300:1025–1026, 2008Google Scholar

10. Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al: Spillover effects on treatment of adult depression in primary care after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1198–1205, 2007Google Scholar

11. Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al: Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:42–50, 2008Google Scholar

12. Wingert TD, Kralewski JE, Lindquist TJ, et al: Constructing episodes of care from encounter and claims data: some methodological issues. Inquiry 32:430–443, 1995Google Scholar

13. Keeler EB, Wells KB, Manning WG, et al: The Demand for Episodes of Mental Health Services. Report R-3432-NIMH. Santa Monica, Calif, RAND, 1986Google Scholar

14. Wells KB, Roland S, Sherbourne CD, et al: Caring for Depression: A RAND Study. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

15. Kleinman LC, Norton EC: What's the risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Services Research 44:288–302, 2009Google Scholar

16. Barry CL, Busch SH: News media coverage of FDA warnings on pediatric antidepressant use. Pediatrics, in pressGoogle Scholar

17. Olfson M, Marcus S, Weissman MM, et al: National trends in the use of psychotropic medications by children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:514–521, 2002Google Scholar

18. Zito JM, Safer JD, DosReis S, et al: Psychotropic practice patterns for youth: a 10-year perspective. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 157:17–25, 2003Google Scholar

19. Ma J, Lee KV, Stafford R: Depression treatment during outpatient visits by US children and adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 37:434–442, 2005Google Scholar

20. Kessler, RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990–2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar