Prevalence of Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and HIV Infections Among Patients in a Psychiatric Hospital in Greece

The worldwide prevalence of infections caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), or HIV among psychiatric patients is of concern ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Although specific prevalence rates vary by settings, patients with severe mental illness are thought to be at increased risk of acquiring any of these above viral infections. This could be attributed to various characteristics of certain subgroups of psychiatric patients, including a higher likelihood of having a substance-related disorder (particularly intravenous drug use) ( 5 ), being single or divorced ( 5 ), practicing risky sexual behavior ( 6 ), and having reduced awareness about the potential modes of transmission of infectious diseases and of relevant protective measures ( 7 ). Factors that may also be associated with an increased risk of transmission among psychiatric patients include exposure to violent social behavior ( 6 ) as well as substandard living or hospitalization conditions ( 3 ).

In this context, we sought to evaluate the seroprevalence rates of HBV, HCV, and HIV infection in the population of a specialized psychiatric hospital in Greece.

Methods

The study reported here is a retrospective analysis of serological data from patients admitted to the 415-bed Psychiatric Hospital of Thessaloniki from May 2005 to April 2007. This hospital admits only adults, hosts two university psychiatric clinics and an onsite medical and emergency department, and serves as a tertiary care center for the District of Macedonia, Greece, which has approximately 2.5 million inhabitants. The hospital also has several extramural units that provide social support and medical care to patients with substance-related disorders. The serological tests analyzed in this study were ordered in the context of routine clinical practice by attending physicians, who also informed patients about their test results. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the scientific council of the hospital.

This study evaluated laboratory results of all psychiatric patients who were referred by the attending physicians to the biopathology laboratory of the hospital for HBV, HCV, or HIV testing during the study period. Patients with substance-related disorders were not included in the main analysis; however, in a later analysis, this group of patients was compared with psychiatric patients in short-term hospitalization units and psychiatric patients in "other" units. We distinguished between psychiatric patients and patients with substance-related disorders by looking at the type of the referring clinic or unit. We excluded from further analysis persons whose psychiatric status could not be validated, such as hospital personnel, outpatients of the onsite medical department, individuals requesting health certificates, and patients whose referring clinic or unit was unknown.

Routinely, fasting venous blood samples were collected during morning hours in the biopathology laboratory or in hospital units and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for six minutes. Serological tests that were evaluated included hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs), hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc), hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), and HIV antigen and antibody combined assay (HIV Ab and Ag). The HIV Ab and Ag combined assay assesses both the presence of the p54 antigen and the antibody to HIV1 or HIV2 with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 99.6% ( 8 ). All of the above-mentioned tests were performed with a chemiluminescent immunoassay using the Architect i2000SR platform (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, Illinois).

All serological data that were relevant to the study were retrieved from the computerized database of the biopathology laboratory. All data regarding patient characteristics that were included in this database (consisting of gender and referring clinic) were also extracted. In cases of multiple tests for the same patients, we included in our study either the first positive test for each of the viral diseases studied or the first test in general, if no test was positive.

Data were examined for differences in the rates of the serological markers according to gender or referring clinic. Differences were analyzed at the 95% probability level with the chi square test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows, Release 15.0.0.

Results

A total of 2,204 unique patients were tested for any of the studied viral diseases during the study period. Among these, we excluded 799 patients with substance-related disorders and 600 individuals who were not psychiatric patients (including 49 patients with unknown clinic of origin). Thus 805 unique patients constituted the study population, of whom 585 (73%) were males. Regarding the serological tests performed for study patients, 803 were tested for HBsAg, 793 for anti-HCV, and 739 for the HIV Ag and Ab combined assay. Patients tested for anti-HCV and HIV were all tested for HBsAg (except for two patients).

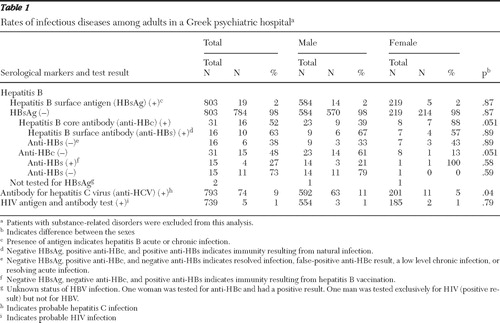

The results of these serological tests, as well as their clinical interpretations, are presented in Table 1 . In brief, 19 of 803 (2%) of patients tested for HBsAg had positive results. This finding means that they harbored HBV, either in the context of an acute or chronic infection or an asymptomatic chronic carrier state. Among the 784 patients whose test result for HBsAg was negative, 31 (4%) underwent additional testing for anti-HBc. Of the latter group of patients, 16 (52%) were found to be positive for anti-HBc, which is indicative of a past immunologic encounter with HBV. Furthermore, of the 15 patients with negative findings for both HBsAg and anti-HBc, four (27%) were found to have positive findings for anti-HBs, which is consistent with past HBV immunization. Of note, all of the four patients with serological evidence of a HBV vaccination were positive for the anti-HCV antibody.

|

Additionally, 74 of the 793 (9%) patients who were examined for the presence of anti-HCV tested positive. Patients with a positive test result for HCV were more likely to be men than women (p=.04). Four patients had serological markers indicative of a dual infection with hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Finally, five of the 739 (1%) patients who were tested for HIV were found to have positive results. Of note, one of the HIV-positive patients was coinfected with HBV and another one was coinfected with HCV.

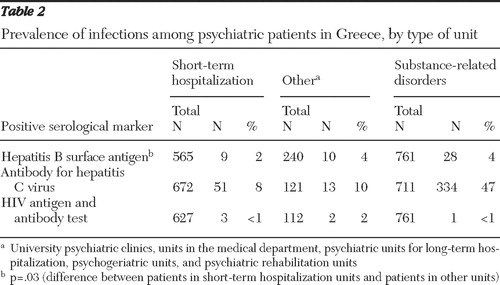

Table 2 shows the results of serological testing for the studied viruses among psychiatric patients hospitalized in short-term units, psychiatric patients hospitalized in "other" units (university psychiatric clinics, units in the supporting medical and emergency department, psychiatric units for long-term hospitalization, psychogeriatric units, and psychiatric rehabilitation units), and patients with substance-related disorders attending specialized extramural units of the hospital. Psychiatric patients in other units were significantly more likely to test positive for HBsAg than psychiatric patients in short-term units (p=.03). No other findings were significant.

|

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that the rates of HBV, HCV, and HIV infections among hospitalized psychiatric patients were 2%, 9%, and 1%, respectively. To interpret the importance of these findings, we should consider national and international data.

Regarding HBV, the observed seroprevalence rates in our study population (2%) did not appreciably deviate from those of the general population of the geographical area of reference (District of Macedonia, Greece). Specifically, the rate of HBsAg in the reference population is 3.0%, according to data for the period of 1998–2006 reported by the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Furthermore, the rate of HBV in our sample of psychiatric patients is comparable to the rates among patients in general hospitals of our country, for whom the seroprevalence of HBV has been estimated to be 2.7% ( 9 ).

The prevalence of HBV in our sample is lower than that observed in most other countries. However, the seropositivity rate of HBsAg among psychiatric patients, excluding those with substance-related disorders, varies widely by geographical setting: it is approximately 3% in India ( 4 ), 15% in the United States ( 1 ), and 18% in Taiwan ( 2 ). A plausible explanation for the lower seroprevalence rate of HBsAg in our study population, compared with relevant international studies, could be a higher percentage of patients in our study population who have been vaccinated against this virus. However, only a small number of patients in our study were given the specific tests that would assess immunization. Also, a considerable proportion of the population in Greece has electively been immunized against HBV ( 10 ). Whether vaccination against HBV should be mandatory for psychiatric patients who may be more susceptible to infection is an important public health issue. Notably, some countries, such as France, have already implemented compulsory vaccination protocols for persons with mental illness.

Regarding HCV, the prevalence of this infection in our study population (9%) was more than ten times as high as it is in the general reference population (.8.%), according to 2006 data from the Hellenic Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. High rates of HCV have also been found in similar studies of psychiatric patients in diverse geographical settings worldwide: 20% in the United States ( 1 ), 7% in Asia ( 2 ), and 11% in Italy ( 3 ). The significance of the high prevalence of HCV among psychiatric patients has several aspects. Specifically, chronic HCV is related to increased psychiatric morbidity ( 11 ), and some agents that are used to treat HCV are often associated with psychiatric adverse events ( 12 ). Moreover, psychiatric patients may have poor compliance with treatment for HCV, unless they receive special attention and monitoring ( 13 ). Therefore, the prognosis of comorbid HCV, HBV, and serious mental illness is often found to be adversely affected.

Regarding HIV infection, .7% of our study population had positive tests, compared with .2% of documented HIV infection in the general population of our country, which is lower than the .8% estimated prevalence worldwide ( 14 ). Of note, rates in Greece of coinfection of HIV and hepatitis lie in the range of 12% for HIV and HBV coinfection and 8% for HIV and HCV coinfection ( 15 ). The prevalence of HIV infection in our study was lower than the prevalence found by similar studies of psychiatric patients worldwide, among whom the prevalence of HIV infection has been estimated to be from 1% to 6% ( 1 , 4 , 5 ). However, these differences may be attributed to the difference of the prevalence of the disease in the general population in different settings.

To better evaluate the internal validity of our study, we assessed the prevalence of each of the viral diseases studied among patients with substance-related disorders, most of whom are intravenous drug users ( Table 2 ). The prevalence of HBV and HCV in this group of patients was equivalent to the prevalence of these infections among intravenous drug users in our country in 2006. Specifically, according to data on Greece from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, the prevalence of HBV among intravenous drug users lies between 2% and 9%, HCV between 43% and 66%, and HIV infection between 0% and .7%. These data support the validity of the methods used in our study. It is noteworthy that almost 50% of the patients with substance-related disorders who were tested for HCV in our study hospital showed positive serological evidence of HCV infection. This figure, which is similar to the rate in the population of intravenous drug users in Greece, highlights the high risk of blood-borne transmission of HCV through needle sharing in intravenous drug use ( 1 , 5 ).

In the interpretation of our findings, several limitations should be considered. First, the potential for selection bias should be analyzed. Patients with a higher clinical suspicion for any of the viral diseases studied herein may have been more likely to be referred for relevant testing, or conversely, patients with known infections may have been less likely to be subjected to retesting. However, it was common practice among physicians in our study hospital to order serological tests for all admitted patients who did not have prior documentation of their serological status for any of the studied viruses. Thus we assume that our study population provides adequate coverage of the total actual number of patients who were admitted for the first time to our study hospital during the study period.

Finally, we did not collect detailed information on the characteristics of patients in our study (psychiatric or medical history, or risk-assuming behavioral patterns). Regarding patients' psychiatric history, our study hospital admits persons with all types of psychiatric diagnoses; the major psychiatric diagnoses among hospitalized patients are considered to be bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and depression. It should also be mentioned that we are not aware of any study that has examined the risk factors among psychiatric patients in Greece for acquisition of any of the viral infections examined in this brief report. However, the risk factors for HCV, HBV, or HIV infection among all patients in Greece generally correspond to those recognized in other developed countries ( 9 ).

Despite the above limitations, our study contributes to the body of literature on a universal multifaceted problem that attracts growing concern. Such data are relatively scarce regarding European countries ( 3 , 7 ). We consider that the risk of acquisition of the viral diseases we studied is considerable among psychiatric patients. An increased risk of transmission would apply not only to patients but also to personnel and visitors. According to our data, greater attention should be paid to HCV, which could be characterized as endemic in residential institutions for persons with mental illness ( 16 ). Moreover, many of the cases of HCV infection can be cryptogenic in origin, rendering the prevention of transmission in a common residence setting problematic.

Conclusions

Serological evidence of HCV infection was found in 9% of tested patients, which is a figure several-fold higher than the prevalence in the general reference population. The prevalence of HBV infection (2%) was found to be equivalent to that of the general reference population, whereas the prevalence of HIV infection was approximately three times higher in our sample than in the general population in Greece (.7% versus .2%). Because the identification of psychiatric patients infected with any of the above viruses would aid in the prevention of transmission as well as in optimizing medical management, we suggest the implementation of relevant screening protocols, coupled with application of infection control measures.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31–37, 2001Google Scholar

2. Chang T, Lin H, Yen Y, et al: Hepatitis B and hepatitis C among institutionalized psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Journal of Medical Virology 40:170–173, 1993Google Scholar

3. Di Nardo V, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G, et al: Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus among personnel and patients of a psychiatric hospital. European Journal of Epidemiology 11:239–242, 1995Google Scholar

4. Carey MP, Ravi V, Chandra PS, et al: Prevalence of HIV, Hepatitis B, syphilis, and chlamydia among adults seeking treatment for a mental disorder in southern India. AIDS and Behavior 11:289–297, 2007Google Scholar

5. Himelhoch S, McCarthy JF, Ganoczy D, et al: Understanding associations between serious mental illness and HIV among patients in the VA health system. Psychiatric Services 58:1165–1172, 2007Google Scholar

6. Essock S, Dowden S, Constantine N, et al: Risk factors for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:836–841, 2003Google Scholar

7. Grassi L, Biancosino B, Righi R, et al: Knowledge about HIV transmission and prevention among Italian patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 52:679–681, 2001Google Scholar

8. Kwon JA, Yoon SY, Lee CK, et al: Performance evaluation of three automated human immunodeficiency virus antigen-antibody combination immunoassays. Journal of Virological Methods 133:20–26, 2006Google Scholar

9. Koulentaki M, Ergazaki M, Moschandrea J, et al: Prevalence of hepatitis B and C markers in high-risk hospitalised patients in Crete: a five-year observational study. BMC Public Health 1:17, 2001Google Scholar

10. German V, Giannakos G, Kopterides P, et al: Serologic indices of hepatitis B virus infection in military recruits in Greece (2004–2005). BMC Infectious Diseases 6:163, 2006Google Scholar

11. Ozkan M, Corapcioglu A, Balcioglu I, et al: Psychiatric morbidity and its effect on the quality of life of patients with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C. International Journal of Psychiatry Medicine 36:283–297, 2006Google Scholar

12. Hosoda S, Takimura H, Shibayama M, et al: Psychiatric symptoms related to interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C: clinical features and prognosis. Psychiatry Clinical Neurosciences 54:565–572, 2000Google Scholar

13. Mistler LA, Brunette MF, Marsh BJ, et al: Hepatitis C treatment for people with severe mental illness. Psychosomatics 47:93–107, 2006Google Scholar

14. UNAIDS/WHO/UNICEF Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV and AIDS, 2008 Update, Greece. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Available at www.unaids.org/en/CountryResponses/Countries/greece.asp Google Scholar

15. Elefsiniotis S, Paparizos V, Botsi C, et al: Serological profile and virological evaluation of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection among HIV infected patients in Greece. Central European Journal of Public Health 14:22–24, 2006Google Scholar

16. Vellinga A, Van Damme P, Meheus A: Hepatitis B and C in institutions for individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 43:445–453, 1999Google Scholar